Slow but Sure Steps of Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genocide in Gujarat the Sangh Parivar, Narendra Modi, and the Government of Gujarat

Genocide in Gujarat The Sangh Parivar, Narendra Modi, and the Government of Gujarat Coalition Against Genocide March 02, 2005 _______________________________ This report was compiled by Angana Chatterji, Associate Professor, Anthropology, California Institute of Integral Studies; Lise McKean, Deputy Director, Center for Impact Research, Chicago; and Abha Sur, Lecturer, Program in Women's Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; with the support of various members of the Coalition Against Genocide. We acknowledge the critical assistance provided by certain graduate students, who played a substantial role in shaping this report through research and writing. In writing this, we are indebted to the courage and painstaking work of various individuals, commissions, groups and organizations. Relevant records and documents are referenced, as necessary, in the text and in footnotes. Genocide in Gujarat The Sangh Parivar, Narendra Modi, and the Government of Gujarat Contents Gujarat: Narendra Modi and State Complicity in Genocide---------------------------------------------------3 * Under Narendra Modi’s leadership, between February 28 and March 02, 2002, more than 2,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed in Gujarat, aided and abetted by the state, following which 200,000 were internally displaced. * The National Human Rights Commission of India held that Narendra Modi, as the chief executive of the state of Gujarat, had complete command over the police and other law enforcement machinery, and is such responsible for the role of the Government of Gujarat in providing leadership and material support in the politically motivated attacks on minorities in Gujarat. * Former President of India, K. R. Narayanan, stated that there was a “conspiracy” between the Bharatiya Janata Party governments at the Centre and in the State of Gujarat behind the riots of 2002. -

National Human Rights Commission Vs State of Gujarat

SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) OF 2003 (Against the Final Judgment and Order dated 27.6.2003 of the Additional Sessions Judge, Fast Track Court No.1, Vadodara, Gujarat passed in Sessions Case No.248 of 2002 APPEALED FROM) in the matter of NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION (PETITIONER) Versus STATE OF GUJARAT AND OTHERS (RESPONDENTS) with CRL.M.P.NO.______of 2003- Application For Exemption From Filing Certified Copy Of Impugned Judgment And Order; and CRL.M.P. NO.______of 2003 - Application For Ad-Interim Exparte Stay Directions; and CRL.M.P. NO. _______of 2003 - Application For Permission To File Special Leave Petiton Against The Judgment And Order Dated 27.6.2003 Of The Addl. Sessions Judge Directly In This Hon’ble Court; and CRL.M.P. NO. _______of 2003 - Application For Permission To Urge Additional Facts; and CRL.M.P. NO. _______of 2003 - Application For Exemption From Filing Official Translation IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION ADVOCATE FOR THE PETITIONER: S.Muralidhar This paper can be downloaded in PDF format from IELRC’s website at http://www.ielrc.org/content/c0302.pdf International Environmental Law Research Centre International Environment House Chemin de Balexert 7 & 9 1219 Châtelaine Geneva, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Table of Content SYNOPSIS AND LIST OF DATES 1 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. __ OF 2003 4 P R A Y E R 21 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO._______OF 2003 22 CERTIFICATE 22 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO._______OF 2003 23 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO.________OF 2003 24 PRAYER 25 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO.________OF 2003 26 CRL.M.P. -

FRESH INVESTIGATION & RE-TRIAL NEEDS to Be ORDERED in These

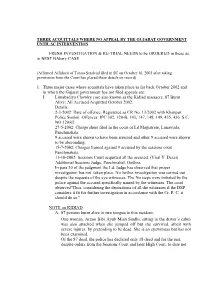

THREE ACQUITTALS WHERE NO APPEAL BY THE GUJARAT GOVERNMENT UNTIL SC INTERVENTION FRESH INVESTIGATION & RE-TRIAL NEEDS to be ORDERED in these as in BEST BAkery CASE (Affirmed Affidavit of Teesta Setalvad filed in SC on October 16, 2003 after taking permission from the Court has placed these details on record) 1. Three major cases where acquittals have taken place as far back October 2002 and in which the Gujarat government has not filed appeals are: I. Limabadiya Chowky case also known as the Kidiad massacre. 87 Burnt Alive; All Accused Acquitted October 2002. Details: 2-3-2002: Date of offence. Registered as CR No. 13/2002 with Khanpur Police Station. Offences: IPC 302, 120-B, 143, 147, 148, 149, 435, 436 S.C. NO 120/02 27-5-2002: Charge sheet filed in the court of Ld Magistrate, Lunawada, Panchmahals. 9 accused were shown to have been arrested and other 9 accused were shown to be absconding. 15-7-2002: Charges framed against 9 accused by the sessions court Panchmahals. 11-10-2002: Sessions Court acquitted all the accused. (Viral Y. Desai) Additional Sessions Judge, Panchmahal, Godhra. In para 30 of the judgment the Ld. Judge has observed that proper investigation has not taken place. No further investigation was carried out despite the requests of the eye witnesses. The No steps were initiated by the police against the accused specifically named by the witnesses. The court observed"Thus, considering the depositions of all the witnesses if the DSP considers it fit for further investigation in accordance with the Cr. -

Gujarat Orders

Orders Passed by the Commisssion On Gujarat Back Order on Gujarat Dated 1st March, 2002 Order on Gujarat Dated 1st April, 2002 (Substantative Recommendation) Order on Gujarat Dated 1st May, 2002 Order on Gujarat Dated 31st May, 2002 (Substantative Recommendation) Order on Gujarat Dated 10 th June, 2002 Order on Gujarat Dated 1st July, 2002 Order on Gujarat Dated 25 September, 2002 Order on Gujarat Dated 28 October, 2002 DGP, Gujarat assures NHRC about protection to witnesses and victms Instructions issued to all SPs and Commissioners of Police Order on Gujarat Dated 30 June, 2003 “Best Bakery Case” Order on Gujarat Dated 3 July, 2003 “Best Bakery Case” Order on Gujarat Dated 11 July, 2003 “Best Bakery Case” NHRC decides to move the Supreme Court in Best Bakery case Transfer application also moved in respect of 4 other serious cases ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION SARDAR PATEL BHAWAN NEW DELHI Name of the complainant : Suo motu Case No. : 1150/6/2001-2002 Date : 1 March, 2002 CORAM Justice Shri J.S.Verma, Chairperson Dr. Justice K.Ramaswamy, Member Justice Mrs. Sujata V. Manohar, Member Shri Virendra Dayal, Member PROCEEDINGS This matter is registered for suo motu action on the basis of media reports, both print and electronic. In addition, a request on e-mail has also been received requesting this Commission to intervene. This matter relates to the existing serious situation in the State of Gujarat. The news items report a communal flare-up in the State of Gujarat and what is more disturbing, they suggest inaction by the police force and the highest functionaries in the State to deal with this situation. -

The Shaping of Modern Gujarat

A probing took beyond Hindutva to get to the heart of Gujarat THE SHAPING OF MODERN Many aspects of mortem Gujarati society and polity appear pulling. A society which for centuries absorbed diverse people today appears insular and patochiai, and while it is one of the most prosperous slates in India, a fifth of its population lives below the poverty line. J Drawing on academic and scholarly sources, autobiographies, G U ARAT letters, literature and folksongs, Achyut Yagnik and Such Lira Strath attempt to Understand and explain these paradoxes, t hey trace the 2 a 6 :E e o n d i n a U t V a n y history of Gujarat from the time of the Indus Valley civilization, when Gujarati society came to be a synthesis of diverse peoples and cultures, to the state's encounters with the Turks, Marathas and the Portuguese t which sowed the seeds ol communal disharmony. Taking a closer look at the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the authors explore the political tensions, social dynamics and economic forces thal contributed to making the state what it is today, the impact of the British policies; the process of industrialization and urbanization^ and the rise of the middle class; the emergence of the idea of '5wadeshi“; the coming £ G and hr and his attempts to transform society and politics by bringing together diverse Gujarati cultural sources; and the series of communal riots that rocked Gujarat even as the state was consumed by nationalist fervour. With Independence and statehood, the government encouraged a new model of development, which marginalized Dai its, Adivasis and minorities even further. -

Hindutva Watch

UNDERCOVER Ashish Khetan is a journalist and a lawyer. In a fifteen-year career as a journalist, he broke several important news stories and wrote over 2,000 investigative and explanatory articles. In 2014, he ran for parliament from the New Delhi Constituency. Between 2015 and 2018, he headed the top think tank of the Delhi government. He now practises law in Mumbai, where he lives with his family. First published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited, in 2020 1st Floor, A Block, East Wing, Plot No. 40, SP Infocity, Dr MGR Salai, Perungudi, Kandanchavadi, Chennai 600096 Context, the Context logo, Westland and the Westland logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Ashish Khetan, 2020 ISBN: 9789389152517 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. For Zoe, Tiya, Dani and Chris Contents Epigraph Preface Introduction 1 A Sting in the Tale 2 Theatre of Masculinity 3 The Ten-foot-tall Officer 4 Painting with Fire 5 Alone in the Dark 6 Truth on Trial 7 Conspirators and Rioters 8 The Gulbarg Massacre 9 The Killing Fields 10 The Salient Feature of a Genocidal Ideology 11 The Artful Faker 12 The Smoking Gun 13 Drum Rolls of an Impending Massacre 14 The Godhra Conundrum 15 Tendulkar’s 100 vs Amit Shah’s 267 16 Walk Alone Epilogue: Riot after Riot Notes Acknowledgements The Big Nurse is able to set the wall clock at whatever speed she wants by just turning one of those dials in the steel door; she takes a notion to hurry things up, she turns the speed up, and those hands whip around that disk like spokes in a wheel. -

Constitutional Crisis in Gujarat

Constitutional Crisis in Gujarat:- The main cause of the Constitutional crisis is that the Chief Minister of Gujarat is abusing his position as Administrative Head of the State in practically all spheres of the Administration and is violating the Basic Structure of the Constitution and using entire state machinery to defeat the mandate of the Constitution and subvert the cause of public justice. We particularly bring to your notice the following actions of the Government which violates the Basic Structure of the Constitution. a) Abusing his position as a Chief Minister in Administration of Justice and instead of honestly prosecuting those who are guilty of murders, mayhem and wanton destruction of property of hundreds of people are brought to justice and instead he is taking steps to ensure that they go Scot Free. Towards this end he and his administration, including senior partymen and legislators are indulging in activities that amount to tampering with evidence, influencing witnesses and de-railing the justice process. The chief minister is also abusing his powers and specifically patronizing those lawyers who are appearing as counsel for those accused of major crimes by handpicking them as special public prosecutors at high stipends. In 2004, the Supreme Court of India had pulled up the government of Gujarat for subverting the justice system remarking that the “public prosecutors in the 2002 carnage cases were behaving like defence counsel.” Subversion of the Criminal Justice System “...Doraiswamy J and Pasayat J identified serious deficiencies in the manner the case had been investigated and also the manner in which the proceedings in that case had been conducted in the trial court and in the High Court. -

Report on International Religious Freedom 2009: India

India Page 1 of 19 India BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR International Religious Freedom Report 2009 October 26, 2009 The Constitution provides for freedom of religion; however, some state level laws and policies restricted this freedom. The National Government generally respected religious freedom in practice; however, some state and local governments imposed limits on this freedom. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the National Government during the reporting period; however, problems remained in some areas. Some state governments enacted and amended "anticonversion" laws, and police and enforcement agencies often did not act swiftly to counter communal attacks effectively, including attacks against religious minorities. India is the birthplace of several religions--Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism--and the home for more than a thousand years of Jewish, Zoroastrian, Muslim, and Christian communities. The vast majority of Indians of all religious groups lived in peaceful coexistence; however, there were some organized communal attacks against minority religious groups. The country's democratic system, open society, independent legal institutions, vibrant civil society, and freewheeling press all provide mechanisms to address violations of religious freedom when they occur. Violence erupted in August 2008 in Orissa after individuals affiliated with left-wing Maoist extremists killed a Hindu religious leader in Kandhamal, the country's poorest district. According to government statistics, 40 persons died and 134 were injured. Although most victims were Christians, the underlying causes that led to the violence have complex ethnic, economic, religious, and political roots related to land ownership and government-reserved employment and educational benefits. -

Contents: INTRODUCTION 2

Contents: INTRODUCTION 2 VIOLENCE AGAINST GIRLS AND WOMEN 3 IN GUJARAT WOMEN SEEKING JUSTICE 4 THE CASE OF BILQIS YAQOOB RASOOL 4 THE BEST BAKERY CASE 5 STATE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ABUSES BY PRIVATE ACTORS 6 AREAS OF STATE FAILINGS 7 POLICE FAILINGS 7 Failure to prevent violence 7 Failure to protect victims 8 Connivance in the violence 8 Failures to register complaints 8 Failure to investigate 9 FAILINGS OF THE STATE JUDICIARY 10 INADEQUATE STATE MEDICAL SERVICES 11 HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS NOT PROTECTED 11 INADEQUATE RELIEF, REHABILITATION AND COMPENSATION 12 LET DOWN BY THE LAW 13 GOVERNMENT REACTION 13 HOPES FOR SOME VICTIMS – BUT NOT FOR OTHERS 15 RECOMMENDATIONS 15 RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE GOVERNMENT OF GUJARAT 16 RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA AND THE LEGISLATURE 17 amnesty RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 17 international International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London W C1X 0DW United Kingdom W ebsite: www.amnesty.org INDIA Justice, the victim – Gujarat state fails to protect women from violence (Summary Report) which describes in greater detail the failings of the Introduction governments of India and of the state of Gujarat to secure the human rights of Muslim girls and women “The state shall not deny to any person equality before law or in Gujarat. the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.” Article 14 of the Constitution of India. The report focuses on the consistent failure of the state of Gujarat to fulfil its and obligations under “Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by a competent national and international law to exercise due national tribunal for acts violating the fundamental rights diligence with regard to the state’s Muslim minority, granted him by the constitution or the law.” Article 8 of the particularly girls and women. -

When Justice Becomes the Victim the Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat

The Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat When Justice Becomes the Victim The Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat May 2014 International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School http://humanrightsclinic.law.stanford.edu/project/the-quest-for-justice International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic at Stanford Law School Cover photo: Tree of Life jali in the Sidi Saiyad Mosque in Ahmedabad, India (1573) Title quote: Indian Supreme Court Judgment (p.7) in the “Best Bakery” Case: (“When the investigating agency helps the accused, the witnesses are threatened to depose falsely and prosecutor acts in a manner as if he was defending the accused, and the Court was acting merely as an onlooker and there is no fair trial at all, justice becomes the victim.”) The Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat When Justice Becomes the Victim: The Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat May 2014 International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School http://humanrightsclinic.law.stanford.edu/project/the-quest-for-justice Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC AT STANFORD LAW SCHOOL, WHEN JUSTICE BECOMES THE VICTIM: THE QUEST FOR FOR JUSTICE AFTER THE 2002 VIOLENCE IN GUJARAT (2014). International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic at Stanford Law School © 2014 International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic, Mills Legal Clinic, Stanford Law School All rights reserved. Note: This report was authored by Stephan Sonnenberg, Clinical Supervising Attorney and Lecturer in Law with the International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic (IHRCRC). -

DETAILS PARAGRAPH the Complaint by Smt

PAGE / DETAILS PARAGRAPH The complaint by Smt. Jakia Jaffri was filed under Sections – 120b, 302, 193,114,186, Page 1 153a, 187 of the IPC, Section 6 of the Co/m/mission of Inquiry Act, under the Gujarat Police Act and Human Rights Act (dated-8/6/2016) . The inquiry of the complaint was Paragraph 1 handed over to Additional Director General of the Police, Gujarat State. No FIR was registered. With the help of Teesta Setalvad (of the Citizen for Justice and Peace), an application for issuance of mandatory direction to register the said complaint as an FIR, an order to submit the investigation to an independent agency. However, this application was dismissed. The aggrieved further filed a SLP before The Supreme Court with same requests. In furtherance to this, the Supreme Court assigned The Special Investigation Team with the inquiry and responsibility to take steps as required in law. The reports of the members (Shri Malhotra and Himanshu Shukhla) were sent to the Learned Amicus Curiae appointed by the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court held the SIT can carry further investigation with respect to the Amicus Curiae’s observation, at its own option. In the final report submitted by SIT it says that allegation in respect of the offences Page 6 under different acts which have been made on the accused member was not found to be true and there was no sufficient evidences to prove offence against any of the accused Paragraph 2 person and no reasonable cause were found thus, a closure report has been filed. -

Top Ten Taglines

DISCOURAGING DISSENT: Intimidation and Harassment of Witnesses, Human Rights Activists, and Lawyers Pursuing Accountability for the 2002 Communal Violence in Gujarat I. Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 0 II. Background...............................................................................................................................9 III. Cases of Threats, Intimidation and Harassment of Victims, Witnesses, and Activists ........................................................................................................................................................12 Official Harassment................................................................................................................12 1. Threats and harassment of Bilkis Yakub Rasool Patel .............................................13 2. Police Inquiries and Interrogation of Mukhtar Muhammed, Kasimabad Education and Development Society..............................................................................14 3. Police Enquiries and Interrogation of Father Cedric Prakash, Director, Prashant, A Center for Human Rights, Justice and Peace.............................................................17 4. Inquiries by the Charity Commissioner of Ahmedabad against human rights activists.................................................................................................................................18 5. Harrassment of Mallika Sarabhai,