Chapter 2 Basic Concepts on GDI Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FUEL INJECTION SYSTEM for CI ENGINES the Function of a Fuel

FUEL INJECTION SYSTEM FOR CI ENGINES The function of a fuel injection system is to meter the appropriate quantity of fuel for the given engine speed and load to each cylinder, each cycle, and inject that fuel at the appropriate time in the cycle at the desired rate with the spray configuration required for the particular combustion chamber employed. It is important that injection begin and end cleanly, and avoid any secondary injections. To accomplish this function, fuel is usually drawn from the fuel tank by a supply pump, and forced through a filter to the injection pump. The injection pump sends fuel under pressure to the nozzle pipes which carry fuel to the injector nozzles located in each cylinder head. Excess fuel goes back to the fuel tank. CI engines are operated unthrottled, with engine speed and power controlled by the amount of fuel injected during each cycle. This allows for high volumetric efficiency at all speeds, with the intake system designed for very little flow restriction of the incoming air. FUNCTIONAL REQUIREMENTS OF AN INJECTION SYSTEM For a proper running and good performance of the engine, the following requirements must be met by the injection system: • Accurate metering of the fuel injected per cycle. Metering errors may cause drastic variation from the desired output. The quantity of the fuel metered should vary to meet changing speed and load requirements of the engine. • Correct timing of the injection of the fuel in the cycle so that maximum power is obtained. • Proper control of rate of injection so that the desired heat-release pattern is achieved during combustion. -

Heat Release Analysis and Modeling for a Common-Rail Diesel Engine

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2002 Heat Release Analysis and Modeling for a Common-Rail Diesel Engine M. Rajkumar University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Rajkumar, M., "Heat Release Analysis and Modeling for a Common-Rail Diesel Engine. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2002. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2144 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by M. Rajkumar entitled "Heat Release Analysis and Modeling for a Common-Rail Diesel Engine." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Mechanical Engineering. Dr. Ming Zheng, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Dr. Jeffrey W. Hodgson, Dr. David K. Irick Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by M.Rajkumar entitled "Heat Release Analysis and Modeling for a Common-Rail Diesel Engine”. -

Sudden Acceleration in Vehicles with Common Rail Diesel Engines

Sudden Acceleration in Vehicles with Common Rail Diesel Engines by Ronald A. Belt Plymouth, MN 55447 1 July 2016 Abstract: An explanation is given for sudden unintended acceleration (SUA) in vehicles with common rail diesel engines. SUA is explained by an increase in the gain of the common rail pressure controller that leads to more fuel being injected into the engine than the throttle map specifies. The gain increase is caused by an erroneous battery voltage compensation coefficient produced by a negative voltage spike occurring while the battery voltage is being sampled. The erroneous battery voltage compensation coefficient increases the fuel injected into the engine, causing an increase in the engine speed, which causes the next iteration of the throttle map to issue a new common rail pressure set-point that is even higher than the previous one. The result is a runaway engine speed without the driver’s foot being on the accelerator pedal. No diagnostic trouble code (DTC) is produced because all the engine sensors and actuators are working normally except for the battery voltage compensation coefficient, and this compensation coefficient is not checked for an erroneous value. This explains why a majority of SUA incidents occur while the engine is at idle in a parking lot or at stop sign because this is the only time that the battery voltage can be determined by sampling the supply voltage. It also explains why the high engine speeds go away when the ignition is turned off and the engine is restarted, because a new battery voltage sample is taken after restarting that is not affected by a random negative voltage spike. -

Common Rail Design & Field Experience

Common Rail Design & Field Experience Introduction MAN Diesel & Turbo Common Rail MAN Diesel & Turbo is the world’s leading designer and manufacturer of low and medium speed engines – engines from MAN Diesel & Turbo cover an estimated 50% of the power needed for all world trade. We develop two-stroke and four-stroke engines, auxiliary en- gines, turbochargers and propulsion packages that are manufactured both within the MAN Diesel & Turbo Group and at our licensees. The coming years will see a sharp in- increasingly important success factor continuous and load-independ ent con- crease in the ecological and eco- for marine and power diesel engines. trol of injection timing and injection nomical requirements placed on Special emphasis is placed on low load pressure. This means that common rail combustion engines. Evidence of operation, where conventional injection technology achieves, for a given engine, this trend is the further tightening of leaves little room for optimization, as highest levels of flexibility for all load emission standards worldwide, a de- the injection process, controlled by the ranges and yields significantly better re- velopment that aims not only at im- camshaft, is linked to engine speed. sults than any conventional injection proving fuel economy but above all Thus, possibilities for designing a load- system. at achieving clean combustion that indepen dent approach to the combus- is low in emissions. tion pro cess are severely limited. A reliable and efficient CR system for an extensive range of marine fuels has Compliance with existing and upcom- MAN Diesel & Turbo’s common rail tech- been developed and is also able to ing emission regulations with best pos- nology (CR) severs this link in medium handle residual fuels (HFO). -

Air Management System Components

AIR MANAGEMENT SYSTEM Air Management System Components Air Management System Features • The series sequential turbocharger is a low • Series Sequential Turbocharger pressure/high pressure design working in series with a turbocharger actuator on the high pressure • Charge Air Cooler turbine controlling the boost pressures. • Intake Manifold • The charge air cooler is utilized to reduce the temperature of the pressurized air therefore inducing a cooler/denser air • Air Filter/Filter Minder charge into the intake manifold for maximum efficiency. • An air filter/filter minder combination is utilzed to clean • Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR) System the incoming air and provide a means for monitoring the condition of the air filter via the filter minder. • The EGR system is designed to reduce exhaust emissions. 57 EGR Cooler Vertical Throttle Body EGR Valve Turbocharger Actuator Compressor Inlet (from air Turbocharger cleaner) Crossover Tube Low Pressure Turbocharger High Pressure Turbocharger Intake Manifold EGR Cooler Horizontal EGR Diesel Oxidation Catalyst (EDOC) 58 33 Air MANAGEMENT SYSTEM System Flow • Air enters the system through the air filter where particles • The intake manifold directs the cooled air to are removed from the air. The air filter has a filter minder the intake ports of the cylinder heads. on it to warn the operator of a restricted air filter. • The burned air fuel mixture is pushed out of the cylinder into • After the air is filtered, the mass of the air and temperature the exhaust manifold which collects the exhaust and routes are measured by the mass air flow sensor (MAF) and it to the high pressure turbocharger’s turbine wheel. -

CRP Automotive Application Intake Manifold Made in Windform® XT For

CRP Automotive Application Intake Manifold made in Windform® XT for VM Motori SpA Engine RA420DH6 - Turbo Diesel Common Rail 2000cc, 4 Cylinders, 16 Valves, 110 KW @ 4000 Rpm, Euro 4 The modern Turbo Diesel engines have increased their performances compared with “old” Diesel engines. Unfortunately, new severe requirements regarding their emission have to be faced. The use of EGR (Exhaust Gas Recirculation) can help engine manufacturers to keep under control the emissions in order to accomplish to the Euro 4 requirements. In order to improve EGR system VM Motori S.p.A. (Cento, FE – ITALY) decided to test different alternative INTAKE MANIFOLDS. Instead of taking a long projecting and engineering time, VM engineers’ good knowledge of RP techniques allowed to spend only a few weeks to reach the best performance of the manifold and the engine. The study was performed using 3 different models, made by C.R.P. Technology in WINDFORM®XT, the latest carbon fibre filled material, for RP Laser Sintering systems. Each prototype was prepared with a typical lead-time of 2/3 days. This kind of “fast- production” was very useful for VM engineers, shortening 10 times or more the standard lead- time for this kind of product. The 1st Model was called “V1”, and after having realized it was possible to use the WINDFORM®XT INTAKE MANIFOLD without any problems for their dyno tests, they worked on other two releases, “V2” and “V3”, to optimize the partitioning of EGR on each cylinder, reaching the goal of a maximum of 4% of difference among the 4 cylinders (as a target for Euro 4 emission level). -

C8.7 Marine Propulsion Engine

C8.7 MARINE PROPULSION ENGINE 478 bkW (641 bhp) @ 2300 rpm ENGINE SPECIFICATIONS Configuration Aspiration In-line 6, 4-Stroke-Cycle-Diesel Turbocharged, supercharged, aftercooled aspiration Emissions Recreational: Governor U.S. EPA Tier 3 (E5 Cycle - Recreational Electronic only), IMO II (EPA, GL and SeeBG), Recreational Craft Directive (EU) RCD Refill Capacity Commercial: Lube oil system w/ oil filter change: EU Stage IIIA, IMO II (GL and SeeBG), 34 L (8.8 gal) CCNR Stage II through reciprocity with Coolant capacity EU Stage IIIA 41 L/10.6 Gal Rated Engine Speed Oil Change Interval 2300 rpm 250 hrs Bore x Stroke Cooling 117 mm x 135 mm Heat exchanger cooled 4.6 in x 5.3 in C8.7 Marine Propulsion Engine Flywheel Housing U.S. EPA Tier 3 / IMO II Displacement SAE No. 1 with SAE No. 14 8.7 Liter Flywheel (149 teeth 531 cu in Rotation Counterclockwise from flywheel end FEATURES AND BENEFITS OPTIONAL ATTACHMENTS • Electronically controlled supercharger provides industry-leading torque and • Alternators throttle response at low speeds, while maintaining fuel efficiency at high • – 24V 120 amp speeds • – 12V 200 amp • Closed crankcase ventilation system improves engine room cleanliness • Transmission gear oil cooler (engine mounted) • Common rail fuel system enables optimum combustion and low emissions • Additional engine and transmission sensor packages for on or off vessel • Single access point improves serviceability monitoring • Grid heater for improved cold weather starting • Instrument panels • Compatible with Cat Marine Displays • Starting motors – 12V or 24V • Available engine-mounted display panel with start, stop, and engine diagnostics E-RATING (HIGH PERFORMANCE) DEFINITION • 12V or 24V electrical system Typical applications: For vessels operating at rated • gplink ready for remote monitoring load and rated speed up to 8% of the time, or 1/2 hour STANDARD ENGINE EQUIPMENT out of 6, (up to 30% load factor). -

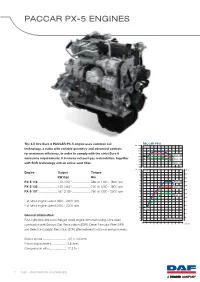

Paccar Px-5 Engines

PACCAR PX-5 ENGINES The 4.5 litre Euro 6 PACCAR PX-5 engine uses common rail PACCAR PX-5 Nm 1000 torque technology, a turbo with variable geometry and advanced controls 900 130123 800 for maximum efficiency. In order to comply with the strict Euro 6 700 600 PX-5 157 emissions requirements, it features exhaust gas recirculation, together 500 PX-5 135 400 with SCR technology and an active soot filter. PX-5 112 300 200 kW 200 270 hp Engine Output Torque output 250 180 kW (hp) Nm 230 160 PX-5 112 ......................112 (152)1 ..................... 580 at 1100 - 1800 rpm PX-5 157 210 1 140 190 PX-5 135 ......................135 (184) ..................... 700 at 1200 - 1800 rpm PX-5 135 170 PX-5 157 ......................157 (213)2 ..................... 760 at 1300 - 2000 rpm 120 150 100 PX-5 112 130 1 at rated engine speed 1800 - 2300 rpm 80 110 2 at rated engine speed 2000 - 2400 rpm 90 60 70 40 50 General information 20 30 Four-cylinder in-line turbocharged diesel engine with intercooling. Ultra clean ECE R24-03 (ISO 1585) EURO 6 -1 combustion with Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR), Diesel Particular Filter (DPF) 8101214161820222426 28 30 x 100 min and Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) aftertreatment for Euro 6 emission levels. Bore x stroke ............................107 x 124 mm Piston displacement ..................4.5 litres Compression ratio .....................17.3 to 1 1 | DAF - PACCAR PX-5 ENGINES PACCAR PX-5 ENGINES DETAILS Main construction Cylinder block cast iron stiffened ladder frame, contoured and deep skirted with cylinder -

Training Program for Automotive Technology 2019

Training Program for Automotive Technology 2019 - 2020 Southeast Asia What drives you, drives us. Introduction Bosch – more than 130 years of system innovation and automotive technology Dear Customers, Today’s vehicles are increasingly complex – and new technologies always present new challenges. An investment in training equips you and your team with the necessary expertise to perform diagnostic tasks, maintenance, and repair effectively and economically on the latest vehicle models. Clearly structured training is essential to ensure your business keeps pace with the latest developments in automotive technology. An overview of the benefits for you: 1. More effective service and faster fault diagnosis 2. Greater repair process reliability 3. Optimal customer service 4. Positive customer feedback and reviews 5. Business management and process optimization 6. Long-term customer loyalty 7. Business success The following pages provide you with an overview of our training program. We very much look forward to meeting you and your employees at our training courses and seminars. For more information and availability of trainings in your area, please contact your local Bosch automotive dealer or get in touch with us at http:// services.bosch-automotive.com/southeast-asia 2 New Training Course starting 2019 We have expanded the range of our trainings with 3 brand new courses & updated our existing trainings with new contents starting 2019. Bosch Diesel Engine Management System DG-2 page 4 NEW Hybrid System HS-1 page 5 COURSES Advanced Driver Assistance System AD-1 page 6 *available from July 2019 onwards* Diagnostics Alternative drives Diesel Automotive technology fundamentals Gasoline Electrical systems and electronics 3 New Training Courses starting 2019 NEW COURSES Diagnostics Bosch Diesel Engine Management System DG-2 Duration: 2 Days | Order Number: 1987 AZ0 015 Participants: Contents: For Experienced technicians, product specialist System overview of diesel engine management. -

Mathematical Modelling of a Diesel Common-Rail System

This document contains a post-print version of the paper Mathematical modelling of a diesel common-rail system authored by Katharina Prinz, Wolfgang Kemmetmüller, and Andreas Kugi and published in Mathematical and Computer Modelling of Dynamical Systems. The content of this post-print version is identical to the published paper but without the publisher’s final layout or copy editing. Please, scroll down for the article. Cite this article as: K. Prinz, W. Kemmetmüller, and A. Kugi, “Mathematical modelling of a diesel common-rail system”, Mathematical and Computer Modelling of Dynamical Systems, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 311–335, 2015. doi: 10.1080/13873954.2014.968590 BibTex entry: @Article{Prinz15, Title = {Mathematical modelling of a diesel common-rail system}, Author = {Prinz, Katharina and Kemmetm\"uller, Wolfgang and Kugi, Andreas}, Journal = {Mathematical and Computer Modelling of Dynamical Systems}, Pages = {311--335}, Volume = {21}, Year = {2015}, Number = {4}, Doi = {10.1080/13873954.2014.968590} } Link to original paper: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13873954.2014.968590 Read more ACIN papers or get this document: http://www.acin.tuwien.ac.at/literature Contact: Automation and Control Institute (ACIN) Internet: www.acin.tuwien.ac.at Vienna University of Technology E-mail: [email protected] Gusshausstrasse 27-29/E376 Phone: +43 1 58801 37601 1040 Vienna, Austria Fax: +43 1 58801 37699 Copyright notice: This is an authors’ accepted manuscript of the article K. Prinz, W. Kemmetmüller, and A. Kugi, “Mathematical modelling of a diesel common-rail system”, Mathematical and Computer Modelling of Dynamical Systems, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 311–335, 2015. -

Powertrain Solutions Technical Information Powertrain Solutions 2 3 Powertrain

Powertrain Solutions Technical Information Powertrain Solutions 2 3 Powertrain. Content Energy for Your Drive. Powertrain Solutions Combustion Electrification Systems Gasoline Connectivity After-treatment Combustion Systems Diesel Efficiency Vehicle Applications Passenger Cars Off-Highway Safe, eco-friendly driving with your own vehicle – ar- rive relaxed at your destination. Few things fascinate Trucks and Buses Recreation people around the world like the issue of mobility. At the same time, mobility today is undergoing funda- 2-Wheelers Marine mental changes. We are one of the leading developers and manufac- 12 System Overviews turers of solutions for efficient combustion engines and after all pioneers in the field of efficient system 12 Diesel Injection and After-treatment System technology and economical vehicle integration in 14 Gasoline Direct Injection System electric vehicles using electric power as an additional 16 Gasoline Port Fuel Injection System energy source. 18 High Voltage Electrification 20 48 Volt Electrification Both fields of innovation ultimately pursue the same goal: Lowering CO2 and emissions. This is the goal pursued by the Powertrain division in the five solu- tion areas electrification, connected energy manage- ment, combustion, exhaust after-treatment and drive- train efficiency. Powertrain Solutions 4 5 Content 22 Electrification Solutions 46 Electrification Solutions Hybrid & Electric Vehicle Hybrid & Electric Vehicle 24 HV Axle Drive with Integrated Inverter 46 12 V Dual Battery Management System 25 HV Power -

Light Vehicle Diesel Engines / James D

LIGHT VEHICLE DIESEL ENGINES James D. Halderman Curt Ward 330 Hudson Street, NY, NY 10013 A01_HALD8726_01_SE_FM.indd 1 12/1/17 1:50 PM Vice President, Portfolio Management: Manager, Rights Management: Andrew Gilfillan Johanna Burke Editorial Assistant: Lara Dimmick Operations Specialist: Deidra Smith Senior Vice President, Marketing: Cover Design: Cenveo Publisher Services David Gesell Full-Service Project Management and Marketing Coordinator: Elizabeth Composition: Abinaya Rajendran, MacKenzie-Lamb Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Director, Digital Studio and Content Printer/Binder: LSC Communications, Inc. Production: Brian Hyland Cover Printer: Phoenix Color/Hagerstown Managing Producer: Jennifer Sargunar Text Font: Helvetica Neue LT W1G Content Producer (Team Lead): Faraz Sharique Ali Copyright © 2019. Pearson Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission should be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or transmis- sion in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise. For information regarding permissions, request forms, and the appropriate contacts within the Pearson Education Global Rights and Permissions department, please visit www.pearsoned.com/ permissions/. Acknowledgments of third-party content appear on the appropriate page within the text. Unless otherwise indicated herein, any third-party trademarks, logos, or icons that may appear in this work are the property of their respective owners, and any references to third-party trade-marks, logos, icons, or other trade dress are for demonstrative or descriptive purposes only. Such references are not intended to imply any sponsorship, endorsement, authorization, or promotion of Pearson’s products by the owners of such marks, or any relationship between the owner and Pearson Education, Inc., authors, licensees, or distributors.