Walter G. Morrill: the Fighting Colonel of the Twentieth Maine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crash- Amundo

Stress Free - The Sentinel Sedation Dentistry George Blashford, DMD tvweek 35 Westminster Dr. Carlisle (717) 243-2372 www.blashforddentistry.com January 19 - 25, 2019 Don Cheadle and Andrew Crash- Rannells star in “Black Monday” amundo COVER STORY .................................................................................................................2 VIDEO RELEASES .............................................................................................................9 CROSSWORD ..................................................................................................................3 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS ....................................................................................................12 SPORTS.........................................................................................................................4 SUDOKU .....................................................................................................................13 FEATURE STORY ...............................................................................................................5 WORD SEARCH / CABLE GUIDE .........................................................................................19 READY FOR A LIFT? Facelift | Neck Lift | Brow Lift | Eyelid Lift | Fractional Skin Resurfacing PicoSure® Skin Treatments | Volumizers | Botox® Surgical and non-surgical options to achieve natural and desired results! Leo D. Farrell, M.D. Deborah M. Farrell, M.D. www.Since1853.com MODEL Fredricksen Outpatient Center, 630 -

Catalog 2018 General.Pdf

TERRY’S COMICS Welcome to Catalog number twenty-one. Thank you to everyone who ordered from one or more of our previous catalogs and especially Gold and Platinum customers. Please be patient when you call if we are not here, we promise to get back to you as soon as possible. Our normal hours are Monday through Friday 8:00AM-4:00PM Pacific Time. You can always send e-mail requests and we will reply as soon as we are able. This catalog has been expanded to include a large DC selection of comics that were purchased with Jamie Graham of Gram Crackers. All comics that are stickered below $10 have been omitted as well as paperbacks, Digests, Posters and Artwork and many Magazines. I also removed the mid-grade/priced issue if there were more than two copies, if you don't see a middle grade of an issue number, just ask for it. They are available on the regular web-site www.terryscomics.com. If you are looking for non-key comics from the 1980's to present, please send us your want list as we have most every issue from the past 35 years in our warehouse. Over the past two years we have finally been able to process the bulk of the very large DC collection known as the Jerome Wenker Collection. He started collecting comic books in 1983 and has assembled one of the most complete collections of DC comics that were known to exist. He had regular ("newsstand" up until the 1990's) issues, direct afterwards, the collection was only 22 short of being complete (with only 84 incomplete.) This collection is a piece of Comic book history. -

Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” the Yellow Peril, Mad Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” The Yellow Peril, Mad Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books Nathan Vernon Madison Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2330 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” The Yellow Peril, German Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books Nathan Vernon Madison Copyright © 2010 Nathan Vernon Madison Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” The Yellow Peril, German Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of History at Virginia Commonwealth University by Nathan Vernon Madison Master of History – Virginia Commonwealth University – 2010 Bachelor of History and American Studies – University of Mary Washington – 2008 Thesis Committee Director: Dr. Emilie E. Raymond – Department of History Second Reader: Dr. John T. Kneebone – Department of History Third Reader: Ms. Cindy Jackson – Special Collections and Archives – James Branch Cabell Library Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December, 2010 i Acknowledgments There are a good number of people I owe thanks to following the completion of this project. -

General Catalog 2021

TERRY’S COMICS Welcome to Catalog number twenty-four. Thank you to everyone who ordered from one or more of our previous catalogs and especially Gold and Platinum customers. Please be patient when you call if we are not here, we promise to get back to you as soon as possible. Our normal hours are Monday through Friday 9:00AM-5:00PM Pacific Time. You can always send e-mail requests and we will reply as soon as we are able. All comics that are stickered below $10 have been omitted as well as paperbacks, Digests, Posters and Artwork and Magazines. I also removed the mid-grade/priced issue if there were more than two copies, if you do not see a middle grade of an issue number, just ask for it. They are available on the regular website www.terryscomics.com. If you are looking for non-key comics from the 1980's to present, please send us your want list as we have most every issue from the past 35 years in our warehouse. We have been fortunate to still have acquired some amazing comics during this past challenging year. What is left from the British Collection of Pre-code Horror/Sci-Fi selection, has been regraded and repriced according to the current market. 2021 started off great with last year’s catalog and the 1st four Comic book conventions. Unfortunately, after mid- March all the conventions have been cancelled. We still managed to do a couple of mini conventions between lockdowns and did a lot of buying on a trip through several states as far east as Ohio. -

March 5, 1948

LOG OF PRESIDENT TRUMAN’S TRIP TO PUERTO RICO, THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA, AND KEY WEST, FLORIDA LOG # 4 * * * * * February 20, 1948 To March 5, 1948 * * * * * WRITTEN AND COMPILED BY LIEUT-COMDR. W. M. RIGDON, U.S.N. CONTENTS LIST OF PARTY I - III THE PRESIDENT’S ITINERARY IV LOG OF THE TRIP 1 - 31 THE PRESIDENT’S PARTY THE PRESIDENT Honorable Julius A. Krug (San Juan to St. Croix only). Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, U.S.N. Honorable John R. Steelman Honorable William D. Hassett Honorable Matthew J. Connelly Honorable Clark M. Clifford Honorable Stanley Woodward Major General Harry H. Vaughan, U.S.A. (Res.) Brigadier General Wallace H. Graham, U.S.A.F. Colonel Robert B. Landry, U.S.A.F. Captain Robert L. Dennison, U.S.N. Mr. Eben A. Ayers STAFF Lieutenant Commander William M. Rigdon, U.S.N. Lieutenant Commander Charles W. Cushman, U.S.N. Lieutenant Commander James V. Bassett, U.S.N.R. Lieutenant (junior grade) Neal H. Kane, U.S.N. Second Lieutenant J. P. Leveritt, (MSC), U.S.A. Mr. Dewey Long Mr. Russell J. McMullin Mr. Arnold W. Hawks Mr. Jack Romagna Chief Photographer’s Mate Gerald P. Pulley, U.S.N. Chief Steward Arthur S. Prettyman, U.S.N. Chief Steward Cayetano Bautista, U.S.N. Chief Cook Jose Palomaria, U.S.N. Chief Cook Januario Sevilla, U.S.N. Chief Radioman John Hughett, U.S.N. Electronics Technician’s Mate 1/c James H. Werdel, U.S.N. Radioman 1/c Paul G. Gladd, U.S.N. -

Wegwerf-Helden! Tillmann Courth Über Vergessene Superhelden Des »Golden Age«, Die Garantiert Keinen Film Bekommen

Wegwerf-Helden! Tillmann Courth über vergessene Superhelden des »Golden Age«, die garantiert keinen Film bekommen. 1 2 Lässt man Menschen raten, wie viele Verkaufszahlen den Rang abläuft). und 9 Verlagshäuser. Das Comicheft und Superhelden die Comics hervorgebracht Marvel Comics betreten das Feld mit der Superheld gehen eine Symbiose ein, haben, bekommt man Antworten wie The Human Torch, dem Sub-Mariner, der zum Motor der aufkommenden Pop- »ein paar Dutzend« oder (ganz Mutige) The Angel und natürlich Captain Ame- kultur wird und deren Produkte schon »ein paar Hundert«. Ich fürchte, es sind rica. MLJ/Archie Comics übrigens prä- bald für Film und Fernsehen adaptiert ein paar Tausend gewesen. Comichis- sentierten mit The Shield (1) 14 Monate werden. Diese ›kostümierten Charak- toriker Mike Benton spricht in seinem vor »Cap« den ersten patriotischen Su- tere‹ waren genuin neu, und ihre Fans Werk Superhero Comics of the Golden perhelden (s. Cover Pep Comics Nr. 1 waren ein neuer Menschenschlag, der Age von »mehreren Hundert allein in vom Januar 1940). Trotz eines respek- einst verächtlich, heute liebevoll Nerds den Jahren des Zweiten Weltkriegs«. tablen Laufs von rund 100 Geschichten genannt wird. Wir alle kennen die »großen Drei« bis zum Herbst 1947 sank The Shield in Große und kleine Zeichenstudios von DC: Superman, Batman und Won- Vergessenheit – hier fehlten dann doch schießen aus dem Boden, welche alle der Woman, zugleich die langlebigsten Stan Lee und Jack Kirby! ihre hausgemachten Superhelden in den Superhelden der Geschichte. Zwischen Gezeichnet werden diese Geschich- Himmel schleudern. Was nicht sofort den Jahren ihrer Schöpfung (1939–41) ten im Grunde von jedem, der einen wieder als lebensunfähiger Klon her- entstehen jedoch auch noch The Flash, Stift halten kann. -

An Interrogation of Morality, Power and Plurality As Evidenced in Superhero Comic Books: a Postmodernist Perspective

An Interrogation of Morality, Power and Plurality as Evidenced in Superhero Comic Books: A Postmodernist Perspective. By Janique Herman 200702391 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science at the University of Fort Hare. Supervisor: Dr. Dianne Shober East London, February 2013 Abstract The desire for heroes is a global and cultural phenomenon that gives a view into society’s very heart. There is no better example of this truism than that of the superhero. Typically, Superheroes, with their affiliation to values and morality, and the notion of the grand narratives, should not fit well into postmodernist theory. However, at the very core of the superhero narrative is the ideal of an individual creating his/her own form of morality, and thus dispensing justice as the individual sees fit in resistance to metanarrative’s authoritarian and restrictive paradigms. This research will explore Superhero comic books, films, videogames and the characters Superman, Spider-Man and Batman through the postmodernist conceptions of power, plurality, and morality. Keywords: Superhero, Comic Book, Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, Power, Plurality, Morality. 2 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Masters of Comparative Literature and Philosophy at the University of Fort Hare. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at any other university. _______________________________ Janique Herman ____________day of ______________, 2013. 3 Dedication This work is dedicated to my amazing husband, Nick Klingelhoeffer, and my terrific family: Dagmar, Davryll, Patricia and Zahvick. -

Postmodern Themes in American Comics Circa 2001-2018

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 5-8-2020 The Aluminum Age: Postmodern Themes in American Comics Circa 2001-2018 Amy Collerton Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Collerton, Amy, "The Aluminum Age: Postmodern Themes in American Comics Circa 2001-2018." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/126 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ALUMINUM AGE: POSTMODERN THEMES IN AMERICAN COMICS CIRCA 1985- 2018 by AMY COLLERTON Under the Direction of John McMillian, PhD ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to update the fan-made system of organization for comic book history. Because academia ignored comics for much of their history, fans of the medium were forced to design their own system of historical organization. Over time, this system of ages was adopted not only by the larger industry, but also by scholars. However, the system has not been modified to make room for comics published in the 21st century. Through the analysis of a selection modern comics, including Marvel’s Civil War and DC Comics’ Infinite Crisis, this thesis suggests a continuation of the age system, the Aluminum Age (2001-the present). Comics published during the Aluminum Age incorporate Postmodern themes and are unique to the historical context in which they were published. -

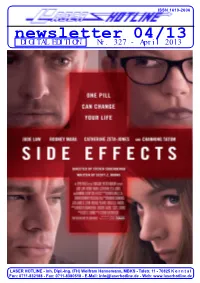

Newsletter 04/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 04/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 327 - April 2013 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 04/13 (Nr. 327) April 2013 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, einer großzügigen DVD-Spende für die Geheimtipp gekürt hat. Der Clou dabei: im liebe Filmfreunde! Inhaber einer Dauerkarte haben wir auch Anschluss an die Filmvorführung geben die noch den offiziellen Festival-Trailer vom Darsteller aus dem Film ein 60-minütiges “Gut Ding braucht Weile” heisst es ja so Videoformat in ein professionelles DCP Bluegrass-Konzert auf der Bühne des Ki- schön in einem alten deutschen Sprichwort. umgewandelt – inklusive eines sauberen nosaals. Gänsehaut ist garantiert! Und Und genau so verhält es sich auch mit un- 5.1-Upmixes des vorhandenen Stereo- ganz wichtig: ausreichend Taschentücher serem Newsletter. Denn auch der braucht Sounds! Wer sich für das “Widescreen mitbringen – der Film hat es in sich! eine ganze Weile, um den Zustand zu errei- Weekend” interessiert, dem sei die offiziel- chen, in dem wir ihn bedenkenlos versen- le Website des Festivals nahegelegt: http:// Und jetzt wünschen wir viel Spaß beim den können. Was genau jetzt passiert ist, www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/ Lesen! wie Sie sicherlich bemerkt haben, seit Sie BradfordInternationalFilmFestival.aspx. das “gut Ding” in Händen halten oder on- Aufgrund unserer Teilnahme am Festival Ihr Laser Hotline Team line lesen. Lange Rede, kurzer Sinn: der wird unser Büro in der Zeit vom Newsletter ist einmal mehr ziemlich ver- 24.04.2013 bis einschließlich 01.05.2013 spätet, weist dafür aber fast doppelt so geschlossen bleiben. -

Allen C. Bluedorn Comic Collection Scope and Contents Note

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace Special Collections 401 Ellis Library Columbia, MO 65201 & Rare Books (573) 882-0076 [email protected] University of Missouri Libraries http://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/ Allen C. Bluedorn Comic Collection Scope and Contents Note The collection was donated by MU faculty member Allen Bluedorn in February 1991 and consists of microform copies of Golden Age era comic books. For specific titles, see the inventory below. Access This microfilm collection is uncatalogued, but the contents of the collection are listed below. These materials are available for use by all patrons during Special Collections service hours or by appointment. Inventory Citation Format: Title. Issues included in the collection. Location (reel number). In cases where issues for a single title are located on more than one reel, a table gives the locations of individual issues. Action Comics. Issues 1-78. 1-5 Reel 116 6-10 Reel 124 11-15 Reel 50 16-20 Reel 109 21-25 Reel 82 26-30 Reel 124 31-35 Reel 90 36-40 Reel 48 41-55 Reel 35 56-60 Reel 50 61-66 Reel 58 67-72 Reel 52 73-78 Reel 54 Airboy. Volume 5, issues 2-6. Reel 104. All Select. Issues 2-11. 2-5 Reel 139 6-10 Reel 169 All-Star. Issues 1-57. 1-5 Reel 38 6-26 Reel 8 27-57 Reel 37 All-Winners (1st series). Issues 2-19, 21. 2-5 Reel 108 6-10 Reel 188 Allen C. -

Board of Review; Holdings, Opinions and Reviews, Volume XI

Judge Advocate General's Department OOARD OF REVIEW Holdings, Opinions and Reviews Volume n including CM 215630 to CM 218166 (1941, 1943) LAW Office of The Judge Advocate General Washington: 1944 01952 CONTE.l'JTS OF VOWME XI CM No. · -~:· Accused Ihte Page 215630 Romero 21 May 1941 1 215729 Lamons, Holmes 19 Nar 1941 29 215734 Rush 22 Mar 1941 35 215787 Reed 16 Apr 1941 43 215788 White 22 Mar 1941 53 215861 Tomalenas 16 Apr 1941 61 215881 Madrid 5 Apr 1941 65 215996 Burton 8 Apr 11.)41 67 216004 Roberts, Miller 29 May 1Y41 69 (Dissenting Opinion) 31 May 11.)41 76 216028 Nix 23 Apr 1941 87 216021.) Brown 12 May 1941 91 216046 Roff 25 Apr 1941 99 216098 Weinrerg 19 Apr 1941 105 216143 Gaines 2 May 1941 109 216152 Wells 5 May 1941 111 216192 · Riggan, Zem.sky 29 Apr 1941 121 2lb239 Gibson 21 May 1941 123 216297 Snyder 3 May 1941 127 216316 Thomas 15 May 1941 129 216.361 Weber 6 May 1941 133 216397 Fleming 28 May 1941 139 2167Cf7 Hester 10 Jul 1941 145 216708 Lockhart 19 Jun 1941 163 216764 Harris 26 Jun 1941 171 216890 Aud 23 Jun 1941 179 216904 Frankie 28 Jun 1941 183 216927 Essex 27 Jun 1941 191 217051 Barton, Boothe 7 Jul 1941 193 217059 Clark 18 Jul 1941 195 217098 Hauptman 8 Aug 1941 207 217104 Bradley 2 Sep 1941 217 217172 Rosenl:aum 15 Jul 1941 225 217207 Barker 24 Jul 1941 229 CY No. Accused Date Page 21?282 Scanlan 31 Jul 1941 233 217283 Collings 2 Sep 1941 239 217383. -

Ca T Alog #19 Terr Y's Comics 2016

TERRY'S COMICS 2016 CATALOG #19 TERRY’S COMICS Welcome to Catalog number nineteen. Thank you to everyone who ordered from one or more of our previous catalogs and especially Gold and Platinum customers. Please be patient when you call if we are not here, we promise to get back to you as soon as possible. This catalog has been expanded to include Magazines, Fanzines, Pulps, Undergrounds and Big Little Books. Most comics that were stickered below $10 have been omitted as well as paperbacks, Digests, Posters and Artwork. I also removed the mid-grade/priced issue if there were more than two copies, if you don't see a middle grade of an issue number, just ask for it. They are available on the regular web-site www.terryscomics.com. If you are looking for non-key comics from the 1980's to present, please send us your want list as we have most every issue from the past 30 years in our warehouse. Over the past year we have been fortunate to keep a steady pace of buying and selling vintage comics. We continue to exhibit at many shows and buy many collections. Comics are fun to read and collect but they are a good investment as well. Buy the best you can afford and store them safely. If your comics are protected, they are likely to continue to accumulate value and you will preserve their appearance. We continue to look for Silver/Bronze age keys as we need to have lots of them to continue doing so many conventions.