From Scripture to Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PASSION of OUR LORD JESUS CHRIST Matthew 26:14-16, 30-27:66

SCRIPTURE READINGS FOR PALM/PASSION SUNDAY, April 5, 2020 Trinity Lutheran Church, Portland, Oregon THE ENTRY GOSPEL + Matthew 21:1-9 When they had come near Jerusalem and had reached Bethphage, at the Mount of Olives, Jesus sent two disciples, 2 saying to them, “Go into the village ahead of you, and immediately you will find a donkey tied, and a colt with her; untie them and bring them to me. 3 If anyone says anything to you, just say this, ‘The Lord needs them.’ And he will send them immediately.” 4 This took place to fulfill what had been spoken through the prophet, saying, 5 “Tell the daughter of Zion, Look, your king is coming to you, humble, and mounted on a donkey, and on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” 6 The disciples went and did as Jesus had directed them; 7 they brought the donkey and the colt, and put their cloaks on them, and he sat on them. 8 A very large crowd spread their cloaks on the road, and others cut branches from the trees and spread them on the road. 9 The crowds that went ahead of him and that followed were shouting, “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest heaven!” The Gospel of the Lord. Thanks be to God. THE PASSION OF OUR LORD JESUS CHRIST Matthew 26:14-16, 30-27:66 One of the twelve, whose name was Judas Iscariot, went to the chief priests 15and said, "What will you give me if I deliver him over to you?" And they paid him thirty pieces of silver.16And from that moment he sought an opportunity to betray him…. -

Online Bible Study July 28 Marriage and Divorce Matthew 19:1-12 When

Online Bible Study July 28 Marriage and Divorce Matthew 19:1-12 When Jesus had finished saying these things, he left Galilee and went into the region of Judea to the other side of the Jordan. 2 Large crowds followed him, and he healed them there. 3 Some Pharisees came to him to test him. They asked, “Is it lawful for a man to divorce his wife for any and every reason?” 4 “Haven’t you read,” he replied, “that at the beginning the Creator ‘made them male and female,’ 5 and said, ‘For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh’? 6 So they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate.” 7 “Why then,” they asked, “did Moses command that a man give his wife a certificate of divorce and send her away?” 8 Jesus replied, “Moses permitted you to divorce your wives because your hearts were hard. But it was not this way from the beginning. 9 I tell you that anyone who divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, and marries another woman commits adultery.” 10 The disciples said to him, “If this is the situation between a husband and wife, it is better not to marry.” 11 Jesus replied, “Not everyone can accept this word, but only those to whom it has been given. 12 For there are eunuchs who were born that way, and there are eunuchs who have been made eunuchs by others—and there are those who choose to live like eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven. -

The Death and Resurrection of Jesus the Final Three Chapters Of

Matthew 26-28: The Death and Resurrection of Jesus The final three chapters of Matthew’s gospel follow Mark’s lead in telling of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus. At each stage Matthew adds to Mark’s story material that addresses concerns of his community. The overall story will be familiar to most readers. We shall focus on the features that are distinctive of Matthew’s version, while keeping the historical situation of Jesus’ condemnation in view. Last Supper, Gethsemane, Arrest and Trial (26:1–75) The story of Jesus’ last day begins with the plot of the priestly leadership to do away with Jesus (26:1–5). As in Mark 14:1-2 they are portrayed as acting with caution, fearing that an execution on the feast of Passover would upset the people (v 5). Like other early Christians, Matthew held the priestly leadership responsible for Jesus’ death and makes a special effort to show that Pilate was a reluctant participant. Matthew’s apologetic concerns probably color this aspect of the narrative. While there was close collaboration between the Jewish priestly elite and the officials of the empire like Pilate, the punishment meted out to Jesus was a distinctly Roman one. His activity, particularly in the Temple when he arrived in Jerusalem, however he understood it, was no doubt perceived as a threat to the political order and it was for such seditious activity that he was executed. Mark (14:3–9) and John (12:1–8) as well as Matthew (26:6–13) report a dramatic story of the anointing of Jesus by a repentant sinful woman, which Jesus interprets as a preparation for his burial (v. -

Jesus and Divorce and Remarriage in Matthew 19

Jesus and Divorce and Remarriage in Matthew 19 By Ekkehardt Mueller Biblical Research Institute Recently, while traveling to Europe, my wife found an interesting article in a magazine, describing the behavior of modern women. Fortunately, a lady wrote the article. She illustrated her point by describing the breaking apart of a marriage. A former gold medalist and world recorder holder, who is still active in pursuing her career in sports, left her husband, a twofold world finalist and now a homemaker, including her two sons, in favor of a lover, who is also a well-known sportsman. The writer the article states that behavior that was considered male, namely leaving spouse and children to live with a new partner, has become common with women. Eva Kohlrusch remarks sarcastically: “Women can congratulate each other. Equality progresses. Women do more and more often what in the past was considered a typical male behavior. They get out of their marriage and their children with their father. She behaves as he has done in the past. We need to invent a totally new concept to protect children from feelings of abandonment.”1 Divorce and remarriage has become a challenge for societies and churches. Ideas of the postmodern age are also influencing Christians. Some abandon the concept of absolute truth. Pluralism is partially accepted. The human has become the ultimate goal. Abundant life is defined as feeling well and being well only. Pain and suffering have become unacceptable. Although there are very difficult circumstances in some marriages, we must recognize that sometimes people may get out of their marriages too easily. -

Matthew 19-20: Commitment to the Kingdom

Life & Teachings of Jesus Lecture 22, page 1 Matthew 19-20: Commitment to the Kingdom In Matthew 19 there is a theme of service to the kingdom of God, which is shown by love towards one’s spouse and toward children, and respect for everyone in the Christian community. These points were made by two antithetical questions. First the Pharisees asked, “How little can I give, what is the minimal service that I can render to my spouse?” And Jesus gave the answer, “You should not be asking that question; you should ask rather what God’s plan for marriage is.” Shortly after that a rich young ruler came and asked, “If I give the maximum to God, can I be sure that God will notice and will in some way reward me or give me my due for this form of service?” Jesus showed that was a faulty question too because he had not really given the maximum to God. Then Peter said, “While he would not give up everything, we have. What then will there be for us? What reward will we have?” Jesus answered Peter and the other disciples, saying, “I tell you the truth, at the renewal of all things, when the Son of Man sits on his glorious throne, you who have followed me will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel. And everyone who has left houses or brothers or sisters or father or mother or children or fields for my sake will receive a hundred times as much and will inherit eternal life. -

Matthew 19:1-12

Matthew 19:1-12 Bible Study Tools and Techniques Cross References: Look up other related verses using a Study Bible. Let Scripture interpret Scripture. Look for first use. Resources: Use a Bible Dictionary, an ESV Study Bible, and Concordance to help you learn and study. Genres: Pay attention to the genre of the passage you are studying (history, poetry, letters, etc). Before you begin your study of the Bible, stop and pray. Ask the Holy Spirit to open your heart to receive the truth of His Word. Pray for humility and grace. Then read Matthew 19:1-12. Comprehension (What does it say?) 1.Why did the Pharisees ask Jesus the question they did? (See verse 3.) 2. Summarize Jesus’s initial answer (verses 4-6). 3. Why does Jesus say Moses allowed divorce? What does that say about God’s intention for marriage? 4. Why do the disciples say it’s better not to marry? What is Jesus’s response? (Eunuchs here refer to those who live a life of abstinence, whether because of a birth defect, castration, or a voluntarily single life, according to the ESV Study Bible Notes.) Interpretation (What does it mean?) 1. Jesus answers the Pharisees by quoting Genesis 2:24 and 5:2. Read these passages. Why did He go back to the creation story as the basis for His answer? 2. The Pharisees were divided into schools, and this topic was one that was hotly debated, with some Pharisees saying divorce was required if the wife was immodest or immoral, and some saying it was allowed if the wife displeased her husband in any way, and required if she was immoral. -

Eunuchs in the Bible 1. Introduction

Acta Theologica Supplementum 7 2005 EUNUCHS IN THE BIBLE ABSTRACT In the original texts of the Bible a “eunuch” is termed saris (Hebrew, Old Testament) or eunouchos (Greek, New Testament). However, both these words could apart from meaning a castrate, also refer to an official or a commander. This study therefore exa- mines the 38 original biblical references to saris and the two references to eunouchos in order to determine their meaning in context. In addition two concepts related to eunuchdom, namely congenital eunuchs and those who voluntarily renounce marriage (celibates), are also discussed. 1. INTRODUCTION The concept of a “eunuch” (a castrate) is described in the Bible prima- rily by two words, namely saris (Hebrew, Old Testament) and eunouchos (Greek, New Testament) (Hug 1918:449-455; Horstmanshoff 2000: 101-114). In addition to “eunuch”, however, both words can also mean “official” or “commander”, while castration is sometimes indirectly referred to without using these terms. This study therefore set out to determine the true appearance of eunuchism in the Bible. The aim was to use textual context and, in particular, any circum- stantial evidence to determine which of the two meanings is applic- able in each case where the word saris (O.T.) or eunouchos (N.T.) occurs in the Bible. All instances of the words saris and eunouchos were thus identified in the original Hebrew and Greek texts of the Bible and compared with the later Septuagint and Vulgate texts, as well as with Afrikaans and English Bible translations. The meanings of the words were determined with due cognisance of textual context, relevant histo- rical customs and attitudes relating to eunuchs (Hug 1918:449-455; Grey 1974:579-85; Horstmanshoff 2000:101-14). -

Fact Sheet for “Judas the Betrayer” Matthew 26:47-56; 27:3-10 Pastor Bob Singer 02/23/2020

Fact Sheet for “Judas the Betrayer” Matthew 26:47-56; 27:3-10 Pastor Bob Singer 02/23/2020 Several years ago I preached a series on a harmonized life of Christ. I had ended that series just before Jesus and the eleven disciples arrived at the Garden of Gethsemane, so I picked-up from there last week. Today we are going to be looking at Judas’ betrayal of Jesus. We are going to be coming around to application at the very end, but there is going to be a lot of Scripture first. I invite you to imagine the scene as the drama unfolds, much as if you were sitting in a theatre watching a play. Jesus had known the day was coming long before he got to this point. Turning the water into wine was the beginning of the signs that Jesus did in Cana (John 2:11). His mother made a request. Read Jesus’ response in John 2:4. Think about that last phrase. This was a reference to his death and resurrection. On multiple occasions during his public ministry he pointed to his coming death and resurrection. In fact he spoke clearly to his disciples about three times this on his last journey from Galilee to Jerusalem. In the Garden he prayed earnestly that this cup may be removed from him if possible, but was absolutely committed to do the Father’s will. Here’s the point. What would happen with Judas was not a surprise to Jesus. Look at events surrounding the Last Supper. Now it was just before the Last Supper. -

Intertextuality and the Portrayal of Jeremiah the Prophet

Scholars Crossing LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations Summer 2013 Intertextuality and the Portrayal of Jeremiah the Prophet Gary E. Yates Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Yates, Gary E., "Intertextuality and the Portrayal of Jeremiah the Prophet" (2013). LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations. 391. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/391 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ________________________________________________________________________________ BIBLIOTHECA SACRA 170 (July–September 2013): 283–300 INTERTEXTUALITY AND THE PORTRAYAL OF JEREMIAH THE PROPHET Gary E. Yates IMOTHY POLK HAS NOTED, “Nothing distinguishes the book of Jeremiah from earlier works of prophecy quite so much as T the attention it devotes to the person of the prophet and the prominence it accords the prophetic ‘I’, and few things receive more scholarly comment.”1 More than simply providing a biographical or psychological portrait of the prophet, the book presents Jeremiah as a theological symbol who embodies in his person the word of Yahweh and the office of prophet.2 In fact the figure of Jeremiah is so central that a theology of the book of Jeremiah “cannot be for- mulated without taking into account the person of the prophet, as the book presents him.”3 The purpose of this article is to explore how intertextual con- nections to other portions of the Bible inform a deeper understand- ing of the portrayal of Jeremiah the prophet and his theological significance in the book of Jeremiah. -

Matthew 26 Matthew 26 Outline

Matthew 26 Then Jesus said to them, ‘All of you will be made to stumble because of Me this night, for it is written: “I will strike the Shepherd, and the sheep of the flock will be scattered”’ (Matthew 26:31). PREVIEW: In Matthew 26, Jesus celebrates the Passover meal with His disciples, He is betrayed and taken to the high priest, and Peter denies knowing Him. Matthew 26 Outline: The Religious Leaders Plot to Kill Jesus - Read Matthew 26:1-5 Mary Anoints Jesus for Burial - Read Matthew 26:6-13 Judas Agrees to Betray Jesus - Read Matthew 26:14-16 The Passover is Prepared - Read Matthew 26:17-19 The Passover is Celebrated - Read Matthew 26:20-25 The Lord’s Supper is Instituted - Read Matthew 26:26-29 Peter’s Denial is Predicted - Read Matthew 26:30-35 Jesus’ Three Prayers - Read Matthew 26:36-46 Jesus’ Betrayal and Arrest - Read Matthew 26:47-56 Two False Witnesses - Read Matthew 26:57-68 Three Denials of Peter - Read Matthew 26:69-75 Engage in the discussion: facebook.com/expoundabq Matthew 26 | Page 1 Questions? Email them to [email protected] The Religious Leaders Plot to Kill Jesus - Read Matthew 26:1-5 1. The Passover, a time to remember Israel’s deliverance out of Egypt, was near. What did Jesus tell His disciples was going to happen during the Passover (v. 2)? 2. Matthew records an event that occurred in the palace of the high priest. Who was the high priest and what occurred in his palace (vv. -

The Beatitudes and Woes of Jesus Christ for the Slow

THE BEATITUDES AND WOES OF JESUS CHRIST FOR THE SLOW SAVOURING OF SERIOUS DISCIPLES by Father Joseph R. Jacobson To the Chinese Christians of our own time who along with survivors of the gulag and the jihad are giving the whole Church a fresh vision of what it means to be called “disciples of Jesus” INTRODUCTORY COMMENTS The Beatitudes and Woes of Jesus Christ are stark. Much of our teaching and preaching based on them is not. Jesus sets them out as ground rules for His disciples. He places them at the very beginning of His special instructions to them, whereas entire theological systems have treated them as an afterthought and relegated them to the end. The problem is that in Jesus’ instructions the Beatitudes are descriptive, not prescriptive. That is, they tell us what discipleship is, not what it ought to be. They spell out the everyday norms of discipleship, not its far off ideals, the bottom line, not the distant goal. This makes us most uncomfortable because, fitting us so poorly they call into question our very right to claim to be disciples of Jesus at all. There can be no question that they are addressed specifically to Jesus’ disciples, both the Beatitudes and the Woes. Matthew makes that plain in his way (Matthew 5:1-2) and Luke makes it plain in his way (Luke 6:20). The fact that Jesus singles them out from the crowds which are all around them, pressing in on them with their own expectations and demands, simply underscores the urgency Jesus felt to clarify what He was expecting of them by way of sheer contrast. -

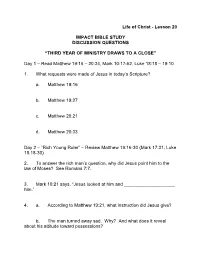

Lesson 20 IMPACT BIBLE STUDY DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Life of Christ - Lesson 20 IMPACT BIBLE STUDY DISCUSSION QUESTIONS “THIRD YEAR OF MINISTRY DRAWS TO A CLOSE” Day 1 – Read Matthew 19:16 – 20:34, Mark 10:17-52, Luke 18:18 – 19:10 1. What requests were made of Jesus in today’s Scripture? a. Matthew 19:16 b. Matthew 19:27 c. Matthew 20:21 d. Matthew 20:33 Day 2 – “Rich Young Ruler” – Review Matthew 19:16-30 (Mark 17:31; Luke 18:18-30) 2. To answer the rich man’s question, why did Jesus point him to the law of Moses? See Romans 7:7. 3. Mark 10:21 says, “Jesus looked at him and ____________________ him.” 4. a. According to Matthew 19:21, what instruction did Jesus give? b. The man turned away sad. Why? And what does it reveal about his attitude toward possessions? c. Share a thought about material possessions versus spiritual treasure. 5. What did Jesus say to His disciples concerning a rich man entering Heaven? 6. a. The response of the astonished disciples was what? b. What is taught in these Scriptures about salvation? Matthew 19:26 John 5:24 Ephesians 2:8, 9 Titus 3:5-7 7. Those who would follow Jesus can expect ultimate reward. From Matthew 19:27-30, what will be the reward for . a. the disciples? b. others who follow Him? Day 3 – “Workers in the Vineyard” – Review Matthew 20:1-16 8. a. What do you remember most about your first job? b. How much does the concept of “fair treatment” affect job satisfaction? 9.