Matthew 19-20: Commitment to the Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 20, 2020

September 20, 2020 The mission of The First Presbyterian Church in Germantown is to reflect the loving presence of Christ as we serve others faithfully, worship God joyfully and share life together in a diverse and generous community. September 20, 2020 "Above all the grace and gifts that Christ gives to his beloved is that of overcoming self." - Francis of Assisi ORDER OF MORNING WORSHIP AT 10:00 AM GATHERING AS GOD’S FAMILY Prelude: And Can it Be? Dan Forrest trans. Isaac Dae Young Welcome and Announcements †*Call to Worship Rev. Kevin Porter One: Coming from places that have seen better days, Many: God bids us to celebrate this day, a day full of new possibilities. One: Coming with our breath taken away by grief, Many: the Holy Spirit breathes new life within us, renewing our connection with God and with one another. One: Coming to worship seeking a hope that will endure, Many: Christ unbinds the fetters that hold us in death, speaking in word and sacrament, and building community for holy service. One: Coming to worship seeking a hope that will endure, All: Coming together even as we are apart. Coming to worship the Lord! *Hymn 464: Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee FAITHFULNESS Joyful, joyful, we adore Thee, God of glory, Lord of love; Hearts unfold like flowers before Thee, Opening to the sun above, Melt the clouds of sin and sadness; Drive the dark of doubt away; Giver of immortal gladness, Fill us with the light of day! All Thy works with joy surround Thee, Earth and heaven reflect Thy rays, Stars and angels sing around Thee, Center of unbroken praise; Field and forest, vale and mountain, Flowery meadow, flashing sea, Chanting bird and flowing fountain Call us to rejoice in Thee. -

Online Bible Study July 28 Marriage and Divorce Matthew 19:1-12 When

Online Bible Study July 28 Marriage and Divorce Matthew 19:1-12 When Jesus had finished saying these things, he left Galilee and went into the region of Judea to the other side of the Jordan. 2 Large crowds followed him, and he healed them there. 3 Some Pharisees came to him to test him. They asked, “Is it lawful for a man to divorce his wife for any and every reason?” 4 “Haven’t you read,” he replied, “that at the beginning the Creator ‘made them male and female,’ 5 and said, ‘For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh’? 6 So they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate.” 7 “Why then,” they asked, “did Moses command that a man give his wife a certificate of divorce and send her away?” 8 Jesus replied, “Moses permitted you to divorce your wives because your hearts were hard. But it was not this way from the beginning. 9 I tell you that anyone who divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, and marries another woman commits adultery.” 10 The disciples said to him, “If this is the situation between a husband and wife, it is better not to marry.” 11 Jesus replied, “Not everyone can accept this word, but only those to whom it has been given. 12 For there are eunuchs who were born that way, and there are eunuchs who have been made eunuchs by others—and there are those who choose to live like eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven. -

Reading the Gospels for Lent

Reading the Gospels for Lent 2/26 John 1:1-14; Luke 1 Birth of John the Baptist 2/27 Matthew 1; Luke 2:1-38 Jesus’ birth 2/28 Matthew 2; Luke 2:39-52 Epiphany 2/29 Matthew 3:1-12; Mark 1:1-12; Luke 3:1-20; John 1:15-28 John the Baptist 3/2 Matthew 3:13-4:11; Mark 1:9-13; Luke 3:20-4:13; John 1:29-34 Baptism & Temptation 3/3 Matthew 4:12-25; Mark 1:14-45; Luke 4:14-5:16; John 1:35-51 Calling Disciples 3/4 John chapters 2-4 First miracles 3/5 Matthew 9:1-17; Mark 2:1-22; Luke 5:17-39; John 5 Dining with tax collectors 3/6 Matthew 12:1-21; Mark 2:23-3:19; Luke 6:1-19 Healing on the Sabbath 3/7 Matthew chapters 5-7; Luke 6:20-49 7 11:1-13 Sermon on the Mount 3/9 Matthew 8:1-13; & chapter 11; Luke chapter 7 Healing centurion’s servant 3/10 Matthew 13; Luke 8:1-12; Mark 4:1-34 Kingdom parables 3/11 Matthew 8:15-34 & 9:18-26; Mark 4:35-5:43; Luke 8:22-56 Calming sea; Legion; Jairus 3/12 Matthew 9:27-10:42; Mark 6:1-13; Luke 9:1-6 Sending out the Twelve 3/13 Matthew 14; Mark 6:14-56; Luke 9:7-17; John 6:1-24 Feeding 5000 3/14 John 6:25-71 3/16 Matthew 15 & Mark 7 Canaanite woman 3/17 Matthew 16; Mark 8; Luke 9:18-27 “Who do people say I am?” 3/18 Matthew 17; Mark 9:1-23; Luke 9:28-45 Transfiguration 3/19 Matthew 18; Mark 9:33-50 Luke 9:46-10:54 Who is the greatest? 3/20 John chapters 7 & 8 Jesus teaches in Jerusalem 3/21 John chapters 9 & 10 Good Shepherd 3/23 Luke chapters 12 & 13 3/24 Luke chapters 14 & 15 3/25 Luke 16:1-17:10 3/26 John 11 & Luke 17:11-18:14 3/27 Matthew 19:1-20:16; Mark 10:1-31; Luke 18:15-30 Divorce & other teachings 3/28 -

Jesus and Divorce and Remarriage in Matthew 19

Jesus and Divorce and Remarriage in Matthew 19 By Ekkehardt Mueller Biblical Research Institute Recently, while traveling to Europe, my wife found an interesting article in a magazine, describing the behavior of modern women. Fortunately, a lady wrote the article. She illustrated her point by describing the breaking apart of a marriage. A former gold medalist and world recorder holder, who is still active in pursuing her career in sports, left her husband, a twofold world finalist and now a homemaker, including her two sons, in favor of a lover, who is also a well-known sportsman. The writer the article states that behavior that was considered male, namely leaving spouse and children to live with a new partner, has become common with women. Eva Kohlrusch remarks sarcastically: “Women can congratulate each other. Equality progresses. Women do more and more often what in the past was considered a typical male behavior. They get out of their marriage and their children with their father. She behaves as he has done in the past. We need to invent a totally new concept to protect children from feelings of abandonment.”1 Divorce and remarriage has become a challenge for societies and churches. Ideas of the postmodern age are also influencing Christians. Some abandon the concept of absolute truth. Pluralism is partially accepted. The human has become the ultimate goal. Abundant life is defined as feeling well and being well only. Pain and suffering have become unacceptable. Although there are very difficult circumstances in some marriages, we must recognize that sometimes people may get out of their marriages too easily. -

Topic: the Gospel Preached by Jesus Date: February 26, 2020 Introduction

Topic: The Gospel preached by Jesus Date: February 26, 2020 Introduction: It is generally taught that Jesus proclaimed a gospel that was no different from that given to the Apostle Paul, the apostle of the Gentiles, but is this really true? This study will examine aspects of the gospel account according to Matthew, in comparison to the gospel which was delivered to Paul. The word “gospel” means “a good message” and first occurs in Matthew 4:23. The subject of the good message is determined by the context of the passage: for example, we are told Jesus preached “the gospel of the kingdom” (Matthew 4:23); yet Paul was “to testify the gospel of the grace of God” which he received of the Lord Jesus (Acts 20:24). Paul also taught the Galatians the gospel to which they were called was “the grace of Christ” (Galatians 1:6). What, then is the essence of the “gospel of the kingdom” declared by Jesus, and are we to understand that Jesus instructed Paul to preach the very same gospel? Study: 1. Starting with the work of John the Baptist: a. Read Matthew 3:1-12 i. v.2 what is it to “repent”, and of what was to be repented? 1. Read Acts 19:1-7; how does this passage explain John’s baptism? ii. The Apostle Paul also speaks of repentance on several occasions: 1. Read 2Corinthians 7:8-10; what is the matter of repentance? 2. Read Romans 11:25-32; what is the matter of repentance? 3. Read 2Timothy 2:24-26; what is the matter of repentance? iii. -

Matthew 20:17-28 – Lent 4 – 3/21/2020

Pastor Daniel Waldschmidt – Matthew 20:17-28 – Lent 4 – 3/21/2020 Imagine an organizational chart for a company or a government. That organizational chart probably has the most powerful person at the top: the CEO or the president or the king. And then under him are his second and third and fourth in command and it goes on from there. Now imagine an organizational chart where the king or the president or the CEO is on the bottom. Today Jesus says that that is the organizational chart for the kingdom of God, with the Lord taking the lowest place and serving everybody else.1 Today Jesus says, “Just as the Son of Man did not come to be served but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Matthew 20:28). And Jesus tells us that if we want to be great in the Kingdom of God, we need to take the lowest place and serve others. You see in the Kingdom of God everything is different. Today we see the Kingdom’s Way of Greatness. And the Kingdom’s Way of Greatness is to Suffer with Jesus and to Serve like Jesus. Follow the Kingdom’s Way of Greatness I. Suffer with Jesus II. Serve like Jesus First, Follow the Kingdom’s Way of Greatness: Suffer with Jesus. In the Gospel for today from Matthew chapter 20 Jesus was going up to Jerusalem. And he was going up to Jerusalem to suffer and die. He wanted to prepare his disciples for this and so he took them aside and told them what was going to happen to him. -

Matthew 19:1-12

Matthew 19:1-12 Bible Study Tools and Techniques Cross References: Look up other related verses using a Study Bible. Let Scripture interpret Scripture. Look for first use. Resources: Use a Bible Dictionary, an ESV Study Bible, and Concordance to help you learn and study. Genres: Pay attention to the genre of the passage you are studying (history, poetry, letters, etc). Before you begin your study of the Bible, stop and pray. Ask the Holy Spirit to open your heart to receive the truth of His Word. Pray for humility and grace. Then read Matthew 19:1-12. Comprehension (What does it say?) 1.Why did the Pharisees ask Jesus the question they did? (See verse 3.) 2. Summarize Jesus’s initial answer (verses 4-6). 3. Why does Jesus say Moses allowed divorce? What does that say about God’s intention for marriage? 4. Why do the disciples say it’s better not to marry? What is Jesus’s response? (Eunuchs here refer to those who live a life of abstinence, whether because of a birth defect, castration, or a voluntarily single life, according to the ESV Study Bible Notes.) Interpretation (What does it mean?) 1. Jesus answers the Pharisees by quoting Genesis 2:24 and 5:2. Read these passages. Why did He go back to the creation story as the basis for His answer? 2. The Pharisees were divided into schools, and this topic was one that was hotly debated, with some Pharisees saying divorce was required if the wife was immodest or immoral, and some saying it was allowed if the wife displeased her husband in any way, and required if she was immoral. -

Eunuchs in the Bible 1. Introduction

Acta Theologica Supplementum 7 2005 EUNUCHS IN THE BIBLE ABSTRACT In the original texts of the Bible a “eunuch” is termed saris (Hebrew, Old Testament) or eunouchos (Greek, New Testament). However, both these words could apart from meaning a castrate, also refer to an official or a commander. This study therefore exa- mines the 38 original biblical references to saris and the two references to eunouchos in order to determine their meaning in context. In addition two concepts related to eunuchdom, namely congenital eunuchs and those who voluntarily renounce marriage (celibates), are also discussed. 1. INTRODUCTION The concept of a “eunuch” (a castrate) is described in the Bible prima- rily by two words, namely saris (Hebrew, Old Testament) and eunouchos (Greek, New Testament) (Hug 1918:449-455; Horstmanshoff 2000: 101-114). In addition to “eunuch”, however, both words can also mean “official” or “commander”, while castration is sometimes indirectly referred to without using these terms. This study therefore set out to determine the true appearance of eunuchism in the Bible. The aim was to use textual context and, in particular, any circum- stantial evidence to determine which of the two meanings is applic- able in each case where the word saris (O.T.) or eunouchos (N.T.) occurs in the Bible. All instances of the words saris and eunouchos were thus identified in the original Hebrew and Greek texts of the Bible and compared with the later Septuagint and Vulgate texts, as well as with Afrikaans and English Bible translations. The meanings of the words were determined with due cognisance of textual context, relevant histo- rical customs and attitudes relating to eunuchs (Hug 1918:449-455; Grey 1974:579-85; Horstmanshoff 2000:101-14). -

Luke 19:28-40 Entry Into Jerusalem • Let’S Read It

4/2/2019 Luke’s Gospel Chapters 16-24 Opening Prayer Four Sessions Left in this Luke Bible Study a. April 3 – Entry into Jerusalem, Last Supper & Passion b. April 10 – The Resurrection of Jesus c. April 17 – The Film “Invictus” Luke 19:28-40 Entry Into Jerusalem • Let’s read it. What strikes you? a. There were many grand entries into Jerusalem like that of Alexander the Great 300 years before Jesus. He praised Jerusalem, its temple, and with the acquiescence of the temple leaders, he offered (pagan) sacrifice in the Jerusalem Temple. b. They were similar to Generals entering Rome and parading in procession after a great military victory, pulled by white horses in a chariot where the victorious general wears a crown of laurel made of an aromatic evergreen. c. The conquered kings, people, and property were paraded for everyone to see, so that the people could praise the general, proclaiming words like “Godspell” or “Good News.” d. The Roman soldiers and General would often proclaim words like “Godspell” or “Gospel” or “Good News,” that is, of a Roman victory, so let’s celebrate. e. This is where Mark gets the name “Gospel” yet it is a very different kind of “Good News” that Mark and the others proclaim about Jesus. f. Jesus’ entry is similar to these, in that, he is riding an animal and people acclaim him, praising God, “Hosanna, Blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord.” g. Jesus’ entry is quite different: he rides a donkey, will cleanse the temple, wears not a crown of laurel but will wear a crown of thorns. -

The Beatitudes and Woes of Jesus Christ for the Slow

THE BEATITUDES AND WOES OF JESUS CHRIST FOR THE SLOW SAVOURING OF SERIOUS DISCIPLES by Father Joseph R. Jacobson To the Chinese Christians of our own time who along with survivors of the gulag and the jihad are giving the whole Church a fresh vision of what it means to be called “disciples of Jesus” INTRODUCTORY COMMENTS The Beatitudes and Woes of Jesus Christ are stark. Much of our teaching and preaching based on them is not. Jesus sets them out as ground rules for His disciples. He places them at the very beginning of His special instructions to them, whereas entire theological systems have treated them as an afterthought and relegated them to the end. The problem is that in Jesus’ instructions the Beatitudes are descriptive, not prescriptive. That is, they tell us what discipleship is, not what it ought to be. They spell out the everyday norms of discipleship, not its far off ideals, the bottom line, not the distant goal. This makes us most uncomfortable because, fitting us so poorly they call into question our very right to claim to be disciples of Jesus at all. There can be no question that they are addressed specifically to Jesus’ disciples, both the Beatitudes and the Woes. Matthew makes that plain in his way (Matthew 5:1-2) and Luke makes it plain in his way (Luke 6:20). The fact that Jesus singles them out from the crowds which are all around them, pressing in on them with their own expectations and demands, simply underscores the urgency Jesus felt to clarify what He was expecting of them by way of sheer contrast. -

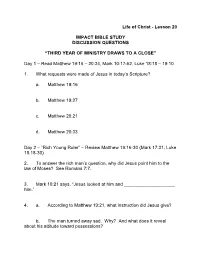

Lesson 20 IMPACT BIBLE STUDY DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Life of Christ - Lesson 20 IMPACT BIBLE STUDY DISCUSSION QUESTIONS “THIRD YEAR OF MINISTRY DRAWS TO A CLOSE” Day 1 – Read Matthew 19:16 – 20:34, Mark 10:17-52, Luke 18:18 – 19:10 1. What requests were made of Jesus in today’s Scripture? a. Matthew 19:16 b. Matthew 19:27 c. Matthew 20:21 d. Matthew 20:33 Day 2 – “Rich Young Ruler” – Review Matthew 19:16-30 (Mark 17:31; Luke 18:18-30) 2. To answer the rich man’s question, why did Jesus point him to the law of Moses? See Romans 7:7. 3. Mark 10:21 says, “Jesus looked at him and ____________________ him.” 4. a. According to Matthew 19:21, what instruction did Jesus give? b. The man turned away sad. Why? And what does it reveal about his attitude toward possessions? c. Share a thought about material possessions versus spiritual treasure. 5. What did Jesus say to His disciples concerning a rich man entering Heaven? 6. a. The response of the astonished disciples was what? b. What is taught in these Scriptures about salvation? Matthew 19:26 John 5:24 Ephesians 2:8, 9 Titus 3:5-7 7. Those who would follow Jesus can expect ultimate reward. From Matthew 19:27-30, what will be the reward for . a. the disciples? b. others who follow Him? Day 3 – “Workers in the Vineyard” – Review Matthew 20:1-16 8. a. What do you remember most about your first job? b. How much does the concept of “fair treatment” affect job satisfaction? 9. -

Notes for Matthew –Chapter 19 (Page 1 of 6)

Notes for Matthew –Chapter 19 (Page 1 of 6) Introduction – The Most Important Sentence in Chapter 19: 1. “With man this is impossible, but with God all things are possible.” (Matt. 26:19 NIV) a. If you can grasp the implications of that one sentence, the rest of the chapter is just further commentary and examples. b. To live a happy, fulfilled life requires getting God involved in the process. The things we consider “impossible” are possible through God. c. Is God “big enough” to handle your problems? Chapter 19 Outline: 1. Jesus teaches on marriage and divorce (Verses 1-10). 2. Jesus teaches on those who choose to live a single life (Verses 11-12). 3. Jesus teaches He is for children too. Christianity is not for adults-only (Verses 13-14). 4. A rich young ruler asking Jesus what it takes to please God (Verses 15-26). a. Jesus uses this opportunity to teach about God and money. 5. Jesus teaches on our rewards in heaven for following him (Verses (27-30). 6. Remember these lessons are about goals (ideal relationships) that God desires for us. Verses 1-2: When Jesus had finished saying these things, he left Galilee and went into the region of Judea to the other side of the Jordan. 2Large crowds followed him, and he healed them there. 1. The first question is, “When Jesus had finished saying these things…” What things? a. In the previous chapter, Jesus was teaching his disciples various lessons on forgiveness and who is the greatest in heaven. b.