Robert Blackburn and American Printmaking by Dr. Deborah Cullen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hubert H. Harrison Papers, 1893-1927 MS# 1411

Hubert H. Harrison Papers, 1893-1927 MS# 1411 ©2007 Columbia University Libraries SUMMARY INFORMATION Creator Harrson, Hubert H. Title and dates Hubert H. Harrison Papers, 1893-1927 Abstract Size 23 linear ft. (19 doucument boxes; 7 record storage cartons; 1 flat box) Call number MS# 1411 Location Columbia University Butler Library, 6th Floor Rare Book and Manuscript Library 535 West 114th Street New York, NY 10027 Hubert H. Harrison Papers Languages of material English, French, Latin Biographical Note Born April 27, 1883, in Concordia, St. Croix, Danish West Indies, Hubert H. Harrison was a brilliant and influential writer, orator, educator, critic, and political activist in Harlem during the early decades of the 20th century. He played unique, signal roles, in what were the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the New Negro/Garvey movement) of his era. Labor and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph described him as “the father of Harlem radicalism” and historian Joel A. Rogers considered him “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time” and “one of America’s greatest minds.” Following his December 17, 1927, death due to complications of an appendectomy, Harrison’s important contributions to intellectual and radical thought were much neglected. In 1900 Harrison moved to New York City where he worked low-paying jobs, attended high school, and became interested in freethought and socialism. His first of many published letters to the editor appeared in the New York Times in 1903. During his first decade in New York the autodidactic Harrison read and wrote constantly and was active in Black intellectual circles at St. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman"

Cummer Museum Presents "Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman" artandobject.com/news/cummer-museum-presents-augusta-savage-renaissance-woman Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY Augusta Savage, Portrait of a Baby, 1942. Terracotta. JACKSONVILLE, Fla. – Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman is the first exhibition to reassess Savage’s contributions to art and cultural history through the lens of the artist-activist. Organized by the Cummer Museum and featuring sculptures, paintings and works on paper, the show is on view through April 7, 2019. Savage is a native of Green Cove Springs, near Jacksonville, and became a noted Harlem Renaissance leader, educator, artist and catalyst for change in the early 20th century. The exhibition, curated by the Cummer Museum and guest curator Jeffreen M. Hayes, Ph.D., brings together works from 21 national public and private lenders, and presents Savage’s small- and medium-size sculptures in bronze and other media alongside works by artists she mentored. Many of the nearly 80 works on view are rarely seen publicly. 1/3 “While Savage’s artistic skill was widely Walter acclaimed nationally and internationally O. during her lifetime, this exhibition Evans provides a critical examination of her artistic legacy,” said Hayes. “It positions Savage as a leading figure whose far- reaching and multifaceted approach to facilitating cultural and social change is especially relevant in terms of today’s interest in activism.” A gifted sculptor, Savage (1892-1962) overcame poverty, racism and sexual discrimination to become one of the most influential American artists of the 20th century, playing a pivotal role in the development of some of this country’s most celebrated artists, including William Artis, Romare Bearden, Gwendolyn Bennett, Robert Blackburn, Gwendolyn Knight, Jacob Lawrence and Norman Lewis. -

Artists Talk On

FRIDAY JANUARY 21 7 PM at the School of Visual Arts Artists Talk On Art Critical Dialogue in the Visual Arts–since 1975 presents Aesthetic Realism: The Opposites in Art & Life What are artists doing in their work that people—including artists—want to do in their lives? The answer is in this great principle stated by poet and founder of the philosophy Aesthetic Realism, Eli Siegel: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” CHAIM KOPPELMAN, printmaker —on “Power and Tenderness in Picasso's Minotauromachy” and on his own “Napoleon series” of prints and drawings Teacher of printmaking at SVA, he is a member of the National Academy, and recently received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society of American Graphic Artists. Koppelman Napoleons on Alligators MARCIA RACKOW, painter and lecturer —on the work of contemporary American realist painters Leon Golub, Alex Katz, and Philip Pearlstein Teacher of the museum/gallery course “The Visual Arts and the Opposites,” she was recently a guest lecturer at The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Katz Cocktail Party DALE LAURIN, architect —on heaviness and lightness in the innovative designs of Santiago Calatrava, architect for the WTC transportation center An associate with Urbane Architects, P.C., he has been a panelist presenting “Housing: A Basic Human Right” at universities, including Harvard, NYU, and the American Institute of Architects. Calatrava Milwaukee Art Museum KEN KIMMELMAN, filmmaker —on the opposition to contempt through the art of animation, showing Disney’s 1929 Skeleton Dance and his own award- winning film Brushstrokes Director of Imagery Film, Ltd., he has made films for the UN and received Emmys for his anti-prejudice public service film The Heart Knows Better and for his contributions to Sesame Street. -

Catalog Price $4.00

CATALOG PRICE $4.00 Michael E. Fallon / Seth E. Fallon COPAKE AUCTION INC. 266 Rt. 7A - Box H, Copake, N.Y. 12516 PHONE (518) 329-1142 FAX (518) 329-3369 Email: [email protected] - Website: www.copakeauction.com UNRESERVED ESTATE AUCTION Plus Selected Additions Saturday May 21, 2016 at 3:00 pm 774 LOTS Featuring Estate fresh 18th and 19th c. furniture, artwork, folk art, period accessories, china, glass, stoneware, primitives & more. Gallery Preview Dates/Times: Thursday May 19, 11-5 PM - Friday May 20, 11-5 PM (*NEW Friday closing time 5pm) Saturday May 21, 12 Noon - 2:45 PM TERMS: Everything sold “as is”. No condition reports in descriptions. Bidder must look over every lot to determine condition and authenticity. Cash or Travelers Checks - MasterCard, Visa and Discover Accepted * First time buyers cannot pay by check without a bank letter of credit * 17% buyer's premium, 20% buyer’s premium for LIVEAUCTIONEERS online purchases, 22% buyer’s premium for INVALUABLE & AUCTIONZIP online purchases. OUR NEXT EVENT: Catalogued Estate Auction – Saturday June 25, 2016 @ 3 PM National Auctioneers Association - NYS Auctioneers Association CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Some of the lots in this sale are offered subject to a reserve. This reserve is a confidential minimum price agreed upon by the consignor & COPAKE AUCTION below which the lot will not be sold. In any event when a lot is subject to a reserve, the auctioneer may reject any bid not adequate to the value of the lot. 2. All items are sold "as is" and neither the auctioneer nor the consignor makes any warranties or representations of any kind with respect to the items, and in no event shall they be responsible for the correctness of the catalogue or other description of the physical condition, size, quality, rarity, importance, medium, provenance, period, source, origin or historical relevance of the items and no statement anywhere, whether oral or written, shall be deemed such a warranty or representation. -

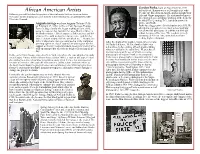

Artist Insert for Web.Indd

Gordon Parks, born on November 30, 1912 in Fort Scott, Kansas was a self-taught artist who became the fi rst African-American photographer for Following you will fi nd short biographies of three infl uential African American Artists. Life and Vogue magazines. He also pursued movie The source for this information came from the website Biography.com published by A&E directing and screenwriting, working at the helm for Television Network. the fi lms The Learning Tree, based on a novel he Augusta Savage was born Augusta Christine Fells wrote, and Shaft. on February 29, 1892, in Green Cove Springs, Florida. Parks faced aggressive discrimination as a child. He Part of a large family, she began making art as a child, attended a segregated elementary school and was using the natural clay found in her area. But her father, a not allowed to participate in activities at his high Methodist minister, didn’t approve of this activity and did school because of his race. The teachers actively whatever he could to stop her. Savage once said that her discouraged African-American students from father “almost whipped all the art out of me.” Despite her seeking higher education. father’s objections, Savage continued to make sculptures After the death of his mother, Sarah, when he was winning a prize in a local county fair which gave her the 14, Parks left home. He lived with relatives for support of the fair’s superintendent, George Graham Currie a short time before setting off on his own, taking who encouraged her to study art despite the racism of the whatever odd jobs, he could fi nd. -

Why Attacks on Public Employee Unions Are on the Rise!

NH Labor News Progressive Politics, News & Information from a Labor Perspective MARCH 6, 2015 NHlabornews.com • New Hampshire Why Attacks on Public Employee Unions Are on the Rise! By Steven Weiner workers have lost their jobs, union-busting is rampant, and in- creasing numbers of Americans are struggling in desperate In recent years throughout America, there have been massive at- poverty. tacks on public employees and the unions that represent them. The latest salvo has come from the newly elected governor of Illi- In an issue of The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, Ellen nois, Bruce Rauner, who, in the name of “fiscal austerity,” issued Reiss explains: an executive order that bars public sector unions from requiring “Because of this failure of business based on private profit, workers they represent to pay fees (often called “fair share pay- there has been a huge effort in the last decade to privatize ments”) to the union. This means that a worker can benefit from publicly run institutions. The technique is to disseminate mas- a union’s collective bargaining with respect to wages, health in- sive propaganda against the public institutions, and also do surance, pensions and job protections, while not financially sup- what one can to make them fail, including through withhold- porting the union by paying their fair share. The purpose behind ing funding from them. Eminent among such institutions are this measure is described by Roberta Lynch, Executive Director the public schools and the post office. The desire is to place of AFSCME Council 31: them in private hands—not for the public good, not so that “I was shocked by the breadth of his assault on labor….It’s the American people can fare well—but to keep profit eco- not limited to public sector unions. -

Marion Harding Artist

MARION HARDING – People, Places and Events Selection of articles written and edited by: Ruan Harding Contents People Antoni Gaudí Arthur Pan Bryher Carl Jung Hugo Perls Ingrid Bergman Jacob Moritz Blumberg Klaus Perls Marion Harding Pablo Picasso Paul-Émile Borduas Pope John Paul II Theodore Harold Maiman Places Chelsea, London Hyères Ireland Portage la Prairie Vancouver Events Nursing Painting Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Ernstblumberg/Books/Marion_Harding_- _People,_Places_and_Events" Categories: Wikipedia:Books Antoni Gaudí Antoni Gaudí Antoni Gaudí in 1878 Personal information Name Antoni Gaudí Birth date 25 June 1852 Birth place Reus, or Riudoms12 Date of death 10 June 1926 (aged 73) Place of death Barcelona, Catalonia, (Spain) Work Significant buildings Sagrada Família, Casa Milà, Casa Batlló Significant projects Parc Güell, Colònia Güell 1See, in Catalan, Juan Bergós Massó, Gaudí, l'home i la obra ("Gaudí: The Man and his Work"), Universitat Politècnica de Barcelona (Càtedra Gaudí), 1974 - ISBN 84-600-6248-1, section "Nacimiento" (Birth), pp. 17-18. 2 "Biography at Gaudí and Barcelona Club, page 1" . http://www.gaudiclub.com/ingles/i_vida/i_vida.asp. Retrieved on 2005-11-05. Antoni Plàcid Guillem Gaudí i Cornet (25 June 1852–10 June 1926) – in English sometimes referred to by the Spanish translation of his name, Antonio Gaudí 345 – was a Spanish Catalan 6 architect who belonged to the Modernist style (Art Nouveau) movement and was famous for his unique and highly individualistic designs. Biography Birthplace Antoni Gaudí was born in the province of Tarragona in southern Catalonia on 25 June 1852. While there is some dispute as to his birthplace – official documents state that he was born in the town of Reus, whereas others claim he was born in Riudoms, a small village 3 miles (5 km) from Reus,7 – it is certain that he was baptized in Reus a day after his birth. -

By Carrie Wilson and Dale Laurin, Journal of the Print

Reprinted from e th f Journalo Print World devoted to contemporary and antique works of fine art on paper July 2018 Dorothy Koppelman Dorothy Koppelman A Life of Art and Ethics (1920-2017) by Carrie Wilson and Dale Laurin t is with great feeling we say that on October 25, 2017 Dorothy characterizes each picture....The fact that they are good as well as Koppelman—artist, Aesthetic Realism consultant, founding director moving depends on the vitality of her touch and the strength of her Iof the Terrain Gallery, and one of the most color, both of which are out of the ordinary.” important women in cultural history —died at “All beauty is a making The Museum of Modern Art included her in the age of 97. Courage, strength of mind, keen, their important 1962 exhibition “Recent Paint - orig inal perception, and deep human sympathy one of opposites, and the ing USA: The Figure,” and she was in exhibi - characterized both her life and her art. making one of opposites tions at the Whitney and Brooklyn Museums. Born in Brooklyn, Dorothy Myers came to Man - is what we are going Awards included a Tiffany Grant; and her folio, hattan as a young painter, looking for what could Poems and Prints, of 2000, is in the collection enable her to become the artist and person she after in ourselves.” of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. hoped to be. She had the great good fortune to —ELI SIEGEL Her work is at once vigorous and tender. There find it. In June of 1942, while working with other are the water towers she loved for their humil - artists on a Win the War parade, she met Chaim Koppelman, who ity and pride; powerful, almost abstract paintings of the wrecked fuse - told her he was studying in classes taught by the great American poet lage of a plane; vivid domestic still lifes; and paintings of the human and critic Eli Siegel, and invited her to join him. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

12 Recent Acquisitions, April 2021 [email protected] 917-974-2420 Full Descriptions Available at Or Click on Any Image

12 Recent Acquisitions, April 2021 [email protected] 917-974-2420 full descriptions available at www.honeyandwaxbooks.com or click on any image WHIMSICAL NINETEENTH-CENTURY SEWING CARDS 1. [DESIGN]. Farbige Ausnähbilder (Colored Sewing Pictures). Germany: circa 1890. $1000. A graphically striking group of large-format nineteenth-century German sewing cards, designed as an entertainment and fine motor exercise for children. Marked with spaced dots for a needle to enter, the images include well-dressed children playing with a puppet, a ball, a parasol, and a shovel. A boy draws a caricature beneath his math problem; a girl prepares her dog for a walk; a younger child assembles all the props for a round of dress-up. There are also three separate images of children wielding pipes, one boy in a top hat actively smoking. Housed in its original color-printed envelope, this set is presumed incomplete: most images appear in one copy, two images in two copies, and one image in three. Not in OCLC. An unusual survival, cards unused and nearly fine. Group of fifteen color-printed sewing cards, measuring 8 x 6 inches. Two cards with light marginal browning. Housed in original envelope with color pictorial pastedown label. LET US NOW PRAISE FAMOUS MEN BY JAMES AGEE AND WALKER EVANS, FROM THE LIBRARY OF HUNTER S. THOMPSON 2. James Agee; Walker Evans; [Hunter S. Thompson]. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, (1960). $2500. First expanded edition, following the 1941 first edition, of a landmark work of American journalism, from the library of Hunter S. -

CREATING COMMUNITY. CINQUE GALLERY ARTISTS MAY 3 – JULY 4, 2021 1 Charles Alston

CREATING COMMUNITY. CINQUE GALLERY ARTISTS MAY 3 – JULY 4, 2021 1 Charles Alston. Emma Amos. Benny Andrews. Romare Bearden. Dawoud Bey. Camille Billops. Robert Blackburn. Betty Blayton-Taylor. Frank Bowling. Vivian Browne. Nanette Carter. Elizabeth Catlett-Mora. Edward Clark. Ernest Crichlow. Melvin Edwards. Tom Feelings. Sam Gilliam. Ray Grist. Cynthia Hawkins. Robin Holder. Bill Hutson. Mohammad Omar Khalil. Hughie Lee-Smith. Norman Lewis. Whitfield Lovell. Alvin D. Loving. Richard Mayhew. Howard McCalebb. Norma Morgan. Otto Neals. Ademola Olugebefola. Debra Priestly. Mavis Pusey. Ann Tanksley. Mildred Thompson. Charles White. Ben Wigfall. Frank Wimberley. Hale Woodruff ESSAY BY GUEST EXHIBITION CURATOR, SUSAN STEDMAN RECOLLECTION BY GUEST PROGRAMS CURATOR, NANETTE CARTER 2 CREATING COMMUNITY. CINQUE GALLERY ARTISTS CREATING COMMUNITY. CINQUE GALLERY ARTISTS Charles Alston. Emma Amos. Benny Andrews. Romare Bearden. Dawoud Bey. Camille Billops. Robert Blackburn. Betty Blayton-Taylor. Frank Bowling. Vivian Browne. Nanette Carter. Elizabeth Catlett-Mora. Edward Clark. Ernest Crichlow. Melvin Edwards. Tom Feelings. Sam Gilliam. Ray Grist. Cynthia Hawkins. Robin Holder. Bill Hutson. Mohammad Omar Khalil. Hughie Lee-Smith. Norman Lewis. Whitfield Lovell. Alvin D. Loving. Richard Mayhew. Howard McCalebb. Norma Morgan. Otto Neals. Ademola Olugebefola. Debra Priestly. Mavis Pusey. Ann Tanksley. Mildred Thompson. Charles White. Ben Wigfall. Frank Wimberley. Hale Woodruff ESSAY BY GUEST EXHIBITION CURATOR, SUSAN STEDMAN RECOLLECTION BY GUEST PROGRAMS CURATOR, NANETTE CARTER MAY 3 — JULY 4, 2021 THE PHYLLIS HARRIMAN MASON GALLERY THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE OF NEW YORK Cinque Gallery Announcement. Artwork by Malcolm Bailey (1947—2011). Cinque Gallery Inaugural, Solo Exhibition, 1969—70. 3 CREATING COMMUNITY. CINQUE GALLERY ARTISTS A CHRONICLE IN PROGRESS Former “306” colleagues.