The Chase : Career of the Compulsive Gambler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“America” on Nineteenth-Century Stages; Or, Jonathan in England and Jonathan at Home

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME by Maura L. Jortner BA, Franciscan University, 1993 MA, Xavier University, 1998 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by It was defended on December 6, 2005 and approved by Heather Nathans, Ph.D., University of Maryland Kathleen George, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Attilio Favorini, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Dissertation Advisor: Bruce McConachie, Ph.D., Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Maura L. Jortner 2005 iii PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME Maura L. Jortner, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation, prepared towards the completion of a Ph.D. in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, examines “Yankee Theatre” in America and London through a post-colonial lens from 1787 to 1855. Actors under consideration include: Charles Mathews, James Hackett, George Hill, Danforth Marble and Joshua Silsbee. These actors were selected due to their status as iconic performers in “Yankee Theatre.” The Post-Revolutionary period in America was filled with questions of national identity. Much of American culture came directly from England. American citizens read English books, studied English texts in school, and watched English theatre. They were inundated with English culture and unsure of what their own civilization might look like. -

V O L . X I V . M a S O N , M I C H I G a N , T H U K S D a Y

• • < NO. VOL. XIV. MASON, MICHIGAN, THUKSDAY. JANUAKY 10, 1889. Oo to Stroud & Co.'fl for furniture. Fine After January.7th, 1889, Pratt & Child Circuit Court rroeeediugs. SAVE MONEY! assgrtraent and low prices. * will sell groceries for cash only. Come and The circuit court for Ingham county published ovory Thursday see what cash will do. Produce the same hj The democratic state convention for convened at the court house. Mason, on Our plan of makinj; it an inducenaent for as cash. * WUITMQBE & CO., nominating a justice of the supreme court Monday last, Judge Erastus Peck presid• subscribers to the Democrat to pay in The following oSicers of the Baptist and two regent to the university, will be ing. Below we give ii synopsis ot the advance, thereby saving 25 cents from the Sunday school, for the ensuing year, were held at Grand Rapids, Feb. 28. business thus far transacted : PX3ICBS : regular subscription price, has proven so elected on Sunday last: Year, $1.50 ; Six monlha, 75 conta : Three A. 0. DuBois assisted in the rendition ol The People vs. .John Bishop—larceny. satisfactory that ive have decided to con• Superintendent—A.J. Uall. monthi.40 centa. Assistant Superintendent—J. W, Clark. Trial by jury and pronounced not guilty. tinue it. Queen Esther at WilllauiHton, last Friday Secretary and Truaauror—Ivittio Kendricks. The People vs. Jo.seph Washington, Al• It is because we need the money, and be• evening', and Selah H. Worden assisted Organist—H. B. Longyear, Asaistant Organist—Minnie Stanton. Our advortlsluK rates are JlOO per column per un- exander Talbot and Robert Wauhington, both Friday and Saturday evenings. -

Archives - Search

Current Auctions Navigation All Archives - Search Category: ALL Archive: BIDDING CLOSED! Over 150 Silver Age Comic Books by DC, Marvel, Gold Key, Dell, More! North (167 records) Lima, OH - WEDNESDAY, November 25th, 2020 Begins closing at 6:30pm at 2 items per minute Item Description Price ITEM Description 500 1966 DC Batman #183 Aug. "Holy Emergency" 10.00 501 1966 DC Batman #186 Nov. "The Jokers Original Robberies" 13.00 502 1966 DC Batman #188 Dec. "The Ten Best Dressed Corpses in Gotham City" 7.50 503 1966 DC Batman #190 Mar. "The Penguin and his Weapon-Umbrella Army against Batman and Robin" 10.00 504 1967 DC Batman #192 June. "The Crystal Ball that Betrayed Batman" 4.50 505 1967 DC Batman #195 Sept. "The Spark-Spangled See-Through Man" 4.50 506 1967 DC Batman #197 Dec. "Catwoman sets her Claws for Batman" 37.00 507 1967 DC Batman #193 Aug. 80pg Giant G37 "6 Suspense Filled Thrillers" 8.00 508 1967 DC Batman #198 Feb. 80pg Giant G43 "Remember? This is the Moment that Changed My Life!" 8.50 509 1967 Marvel Comics Group Fantastic Four #69 Dec. "By Ben Betrayed!" 6.50 510 1967 Marvel Comics Group Fantastic Four #66 Dec. "What Lurks Behind the Beehive?" 41.50 511 1967 Marvel Comics Group The Mighty Thor #143 Aug. "Balder the Brave!" 6.50 512 1967 Marvel Comics Group The Mighty Thor #144 Sept. "This Battleground Earth!" 5.50 513 1967 Marvel Comics Group The Mighty Thor #146 Nov. "...If the Thunder Be Gone!" 5.50 514 1969 Marvel Comics Group The Mighty Thor #166 July. -

Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 048 457 VT 012 300 AUTHOR Doeringer, Peter B.; Piore, Michael J. TITLE Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis. INSTITUTION Harvard Univ., Cambridge, Mass.; Massachusetts Inst. of Tech., Cambridge. SPONS AGENCY Manpower Administration (DOL), Washington, D.C. Office of Manpower Research. PUB DATE May 70 NOTE 344p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$13.16 DESCRIPTORS *Business, Disadvantaged Groups, *Economic Research, Employment Opportunities, *Labor Economics, *Labor Market, Models, *Unemployment ABSTRACT Using data gathered in a series of interviews with management and union officials in over 75 companies between 1964 and 1969, this report analyzes the concept of the internal labor market and describes its relevance for federal manpower policy. The management interviews, which were mostly in personnel, industrial engineering, and operations areas of manufacturing companies, were supplemented by data on the disadvantaged provided by civil rights, poverty, and manpower agencies. The report utilizes the framework established in the study to show that the internal market does not imply inefficiency and may represent an improvement in dealing with structural unemployment. (BH) .4 /.. .118-1`;003 INTERNAL LABOR MARKETS AND MANPOWER ANALYSIS PETER B. DOERINGER Assistant Professor of Economics Harvard University MICHAEL J. PIORE Associate Profe s sor of Economics Massachusetts Institute of Technology ',Jay 1970 This research was preparedunder a contract with the Office of ManpowerResearch, U.S. Departmentof Labor, under the authorityof the Manpower Development and Training Act.Researchers undertakingsuch projects under the Government sponsorshipare encouraged to express their own judgementfreely.Therefore, points of view or opinions stated inthis document do not necessarily represent theofficial position of the Department of Labor. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

GREEN LANTERN (Alan Scott)

GREEN LANTERN (Alan Scott) Serie dedicata alla 1° Lanterna Verde nata nel Settembre del 1941 e proseguita per 38 numeri, fino a Ottobre del 1949. 1) Masquerading Mare! (Finger/Nodell) (11/41- Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) Disease!! (Finger/Nodell) (Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) Arson in the Slums (Finger/Nodell) (Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) Green Lantern in South America (Finger/Nodell) (Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) 2) The Tycoon's Legacy (Finger/Nodell) (12/41- Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) 3) The Living Graveyard of the Sea (Finger/Nodell) (03/42- Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) 4) Green Lantern and Doiby Join the Army part I-II-III-IV (Finger/Nodell) (06/42- Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) 5) The Legion of the Lantern (Finger/Nodell) (09/42- Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) 6) Empire of Exiles (Greene/Nodell) (12/42- Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) 7) The Wizard of Odds (Greene/Nodell) (03/43- Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) 8) The Lady and Her Jewels (Greene/Nodell) (09/43- Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) A Lease On Life (Finger/Nodell) (Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) Company General Use 9) The School for Vandals (Bester/Nodell) (10/43- Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) 10) The Man Who Wanted the World (Bester/Nodell) (12/43- Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) Doiby Dickles' Dismal Discovery (Bester/Nodell) (Protagonista Lanterna Verde [Alan Scott]) 11) The Dastardly Designs of Doiby Dickles -

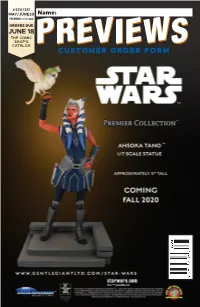

Customer Order Form

#380/381 MAY/JUNE20 Name: PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE JUNE 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Cover COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 1:41:01 PM FirstSecondAd.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:49:06 PM PREMIER COMICS BIG GIRLS #1 IMAGE COMICS LOST SOLDIERS #1 IMAGE COMICS RICK AND MORTY CHARACTER GUIDE HC DARK HORSE COMICS DADDY DAUGHTER DAY HC DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: THREE JOKERS #1 DC COMICS SWAMP THING: TWIN BRANCHES TP DC COMICS TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: THE LAST RONIN #1 IDW PUBLISHING LOCKE & KEY: …IN PALE BATTALIONS GO… #1 IDW PUBLISHING FANTASTIC FOUR: ANTITHESIS #1 MARVEL COMICS MARS ATTACKS RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SEVEN SECRETS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS MayJune20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:41:00 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Cimmerian: The People of the Black Circle #1 l ABLAZE 1 Sunlight GN l CLOVER PRESS, LLC The Cloven Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS The Big Tease: The Art of Bruce Timm SC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Totally Turtles Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS 1 Heavy Metal #300 l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist l HERMES PRESS Titan SC l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: Mistress of Chaos TP l PANINI UK LTD Kerry and the Knight of the Forest GN/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC Masterpieces of Fantasy Art HC l TASCHEN AMERICA Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics Hc Gn l TEN SPEED PRESS Horizon: Zero Dawn #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2019 #9 l TITAN COMICS Negalyod: The God Network HC l TITAN COMICS Star Wars: The Mandalorian: -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

A Theory of Consumer Fraud in Market Economies

A THEORY OF FRAUD IN MARKET ECONOMIES ADISSERTATIONIN Economics and Social Science Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Nicola R. Matthews B.F.A, School of Visual Arts, 2002 M.A., State University College Bu↵alo, 2009 Kansas City, Missouri 2018 ©2018 Nicola R. Matthews All Rights Reserved A THEORY OF FRAUD IN MARKET ECONOMIES Nicola R. Matthews, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2018 ABSTRACT Of the many forms of human behavior, perhaps none more than those of force and fraud have caused so much harm in both social and ecological environments. In spite of this, neither shows signs of weakening given their current level of toleration. Nonetheless, what can be said in respect to the use of force in the West is that it has lost most of its competitiveness. While competitive force ruled in the preceding epoch, this category of violence has now been reduced to a relatively negligible degree. On the other hand, the same cannot be said of fraud. In fact, it appears that it has moved in the other direction and become more prevalent. The causes for this movement will be the fundamental question directing the inquiry. In the process, this dissertation will trace historical events and methods of control ranging from the use of direct force, to the use of ceremonies and rituals and to the use of the methods of law. An additional analysis of transformation will also be undertaken with regards to risk-sharing-agrarian-based societies to individual-risk-factory-based ones. -

Quad Plus: Special Issue of the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs

The Journal of JIPA Indo-Pacific Affairs Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Charles Q. Brown, Jr., USAF Chief of Space Operations, US Space Force Gen John W. Raymond, USSF Commander, Air Education and Training Command Lt Gen Marshall B. Webb, USAF Commander and President, Air University Lt Gen James B. Hecker, USAF Director, Air University Academic Services Dr. Mehmed Ali Director, Air University Press Maj Richard T. Harrison, USAF Chief of Professional Journals Maj Richard T. Harrison, USAF Editorial Staff Dr. Ernest Gunasekara-Rockwell, Editor Luyang Yuan, Editorial Assistant Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator Megan N. Hoehn, Print Specialist Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs ( JIPA) 600 Chennault Circle Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6010 e-mail: [email protected] Visit Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs online at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/. ISSN 2576-5361 (Print) ISSN 2576-537X (Online) Published by the Air University Press, The Journal of Indo–Pacific Affairs ( JIPA) is a professional journal of the Department of the Air Force and a forum for worldwide dialogue regarding the Indo–Pacific region, spanning from the west coasts of the Americas to the eastern shores of Africa and covering much of Asia and all of Oceania. The journal fosters intellectual and professional development for members of the Air and Space Forces and the world’s other English-speaking militaries and informs decision makers and academicians around the globe. Articles submitted to the journal must be unclassified, nonsensitive, and releasable to the public. Features represent fully researched, thoroughly documented, and peer-reviewed scholarly articles 5,000 to 6,000 words in length. -

Dictators: Ethnic American Narrative and the Strongman Genre by David

Dictators: Ethnic American Narrative and the Strongman Genre By David C. Liao B.A., State University of New York, Binghamton 2006 M.A., Brown University Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of English at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2015 © 2015 by David C. Liao This dissertation is accepted in its present form by the Department of English as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date _________ __________________________________________ Deak Nabers, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date _________ __________________________________________ Tamar Katz, Reader Date _________ __________________________________________ Olakunle George, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date _________ __________________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii VITA David Chang Yi Liao was born on July 20, 1984 in Taipei, Taiwan. The child of a diplomat, he has also lived in Houston, Texas and Long Island, New York, as well as spending numerous holidays with his brothers in California. He graduated magna cum laude from the State University of New York at Binghamton in 2006, earning a B.A. in English, with a concentration in Creative Writing. He began pursuing a Master’s Degree in English at Brown University in September of 2006, and began his doctoral studies with the English Department at Brown in the fall of 2008. In the course of completing his Ph.D., he has taught courses in literature and composition at both Brown and Bryant University in Smithfield, R.I. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to thank the English Department at Brown University, who accepted me into their ranks on two separate occasions. -

344 | MAY17 World.Com PREVIEWS

#344 | MAY17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE MAY 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 May17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 4/6/2017 2:29:18 PM C4 Dark Horse.indd 1 4/4/2017 10:33:14 AM MOONSTRUCK #1 B.P.R.D.: THE DEVIL IMAGE COMICS YOU KNOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS AMERICAN WAY: THOSE ABOVE AND THOSE BELOW #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT/ VERTIGO MOEBIUS LIBRARY: THE ART OF SACRED CREATURES EDENA HC #1 DARK HORSE COMICS IMAGE COMICS TMNT/USAGI YOJIMBO IDW ENTERTAINMENT DARK DAYS: SPIDER-MEN II #1 THE CASTING #1 MARVEL COMICS DC ENTERTAINMENT May17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 4/6/2017 3:49:08 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Miraculous Adventures #1 l ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Dreadful Beauty: The Art of Providence TP l AVATAR PRESS INC The Mystery Knight GN l BANTAM / SPECTRA 1 Lady Mechanika: The Clockwork Assassin #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS 1 Go Go Power Rangers #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Sisters of Sorrow #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Belladonna Annual 2017 l BOUNDLESS COMICS Bettie Page #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Centipede #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT The Phantom: President Kennedy’s Mission #1 l HERMES PRESS Rick & Morty: Pocket Like You Stole It #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Robotech #1 l TITAN COMICS The Death of Stalin HC l TITAN COMICS Disney Manga: Tangled GN l TOKYOPOP Faith and the Future Force #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Mobile Suit Gundam Wing Volume 1 GN l VERTICAL COMICS BOOKS 2 Bernie Wrightson: Art & Designs for the Gang of 7 Animation Studio HC l ART BOOKS Kirby: King of Comics Anniversary Edition SC l COMICS