An Examination of the Impact of Paratextual Variables on Response and ROI in Direct Mail Fund-Raising Campaigns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

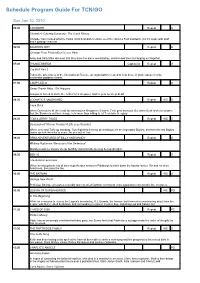

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Jan 10, 2010 06:00 CHOWDER Repeat G Chowder's Catering Company / The Catch Phrase Chowder has created what he thinks is his best dish creation ever! He calls it a Foof sandwich, but it's made with stuff that's garbage material. 06:30 SQUIRREL BOY Repeat G Stranger Than Friction/Don't Cross Here Andy and Salty Mike discover that they have the same weird hobby, which leads them to hanging out together. 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Cry Wolf Part 2 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat G Sweet Dream Baby / Dirt Nappers Lumpus is forced to invite the Jellies for a sleepover and he gets no sleep at all! 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED Repeat WS G Cape Duck When Duck takes all the credit for catching the Shropshire Slasher, Tech gets annoyed. But when Duck starts to suspect that the Slasher is out for revenge, he's more than willing to let Tech take the glory. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES Repeat WS G Sasquashed/ Xtreme Trouble/ A Life Less Guarded When Jerry and Tuffy go camping, Tom frightens them by pretending to be the legendary Bigfoot, but then the real Bigfoot teams up with the mice to scare the wits out of Tom. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY Repeat G Waking Nightmare / Because of the Undertoad Mandy needs her beauty sleep, but Billy risks his hide to keep her up all night. -

Marketing Privacy: a Solution for the Blight of Telemarketing

Marketing Privacy Ian Ayrest Matthew Funktt Unsolicited solicitations in the form of telemarketing calls, email spam andjunk mail impose in aggregate a substantial negative externality on society. Telemarketers do not bear the full costs of their marketing because they do not compensate recipients for the hassle of, say, being interrupted during dinner. Current regulatory responses that give consumers the all-or-nothing option ofregistering on the Internet to block all unsolicited telemarketing calls are needlessly both over- and under inclusive. A better solution is to allow individual consumers to choose the price per minute they would like to receive as compensation for listening to telemarketing calls. Such a "name your own price" mechanism could be easily implemented technologically by crediting consumers' phone bills (a method analogous to the current debits to bills from 1-900 calls). Compensated calling is also easily implemented within current "don't call" statutes simply by giving "don't-call" households the option to authorize intermediaries to connect calls that meet their particular manner or compensation prerequisites. Under this rule, consumers are presumptively made better off by a regime that gives them greater freedom. Telemarketing firms facing higher costs of communication are likely to better screen potential contacts. Consumers having the option of choosing an intermediate price will receive fewer calls, which will be better tailored to their interests, and will be compensatedfor those calls they do receive. Giving consumers the right to be compensated may also benefit some telemarketers. Once consumers are voluntarily opting to receive telemarketing calls (in return for tailored compensation), it becomes possible to deregulate the telemarketers-lifting current restrictions on the time (no night time calls) and manner (no recorded calls). -

Works Cited Entries Core Elements 1

Illinois Valley Community College Writing Center WORKS CITED ENTRIES CORE ELEMENTS 1. Author. 2. Title of source. 3. Title of container, 4. Other contributors, 5. Version, 6. Number, 7. Publisher, 8. Publication date, 9. Location. 1. Author • Begin the entry with the author’s last name, followed by a comma and the rest of the name. Carroll, Lewis. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Bantam, 2006. • When a source has two authors, include them in the order presented in the work. Reverse the first name as described above, follow it with a comma and and, and give the second name in normal order. Sabrio, David and Mitchel Burchfield. Insightful Writing. Houghton Mifflin, 2009. • When a source has three or more authors, reverse the first name as described above and follow it with a comma and et al. Burdick, Anne, et al. Digital_Humanities. MIT P, 2012. • Author refers to the person or group primarily responsible for producing the work, so an editor(s) or corporate author may be listed first in the entry. When a work is published by an organization that is also its author, begin the entry with the title, skipping the author element, and list the organization only as publisher. • When a work is published without an author, do not list the author as “anonymous.” Instead, skip the author element and begin the entry with the work’s title. “Preeclampsia.” Mayo Clinic, 2016, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases_conditions/preeclampsia/basics/definition/con-20031644. 2. Title of Source • Use standard capitalization for titles and subtitles. A title is placed in quotation marks if the source is part of a larger work. -

A Trader's Journey

P A R T I A Trader’s Journey COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL c01 7 June 3, 2014 10:07 PM CHAPTER 1 T he Birth of a Trader t was 1989, and I was California dreamin’. Actually I wasn’t dreaming, I was al- ready in California, living a young single man’s dream. A year or so out of college, I 9 I was residing in sunny Manhattan Beach, California, with a small apartment three blocks from the soft white sand so wonderful that they used it to help create Waikiki Beach in Hawaii. I had graduated the year before, summa cum laude, with a bach- elor’s degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Michigan, a top‐tier engineering school. Then I had turned my back on Massachusetts Institute of Tech- nology (MIT), California Institute of Technology (Cal Tech), Stanford University, Purdue University, and Michigan, all of whom had accepted me in their aerospace master’s degree program. I turned down those great schools to live and work in sunny California, a lifelong dream. I still remember the precise moment I made that fateful decision. On a bitterly cold winter’s day in Ann Arbor, Michigan, I was walking down South University Avenue to one of my fi nal‐semester classes. The wind was blowing so hard in my face that I actually leaned into the wind to see if it would keep me up. At that point, fall- ing face‐fi rst onto the ice‐covered sidewalk would not have been much worse than feeling the stinging wind in my face. -

The Guardian, January 20, 1983

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 1-20-1983 The Guardian, January 20, 1983 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (1983). The Guardian, January 20, 1983. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DAILY GUARDIAN Volume 11 j Number 41 Thursday. January 20.. 1983 ' " : . Wright State'University. Dayton, Ohio iMriaiai ^ B-r-r-r it's cold By LAUNCE RAKE" News Editor Although winter officially arrived- last •month, its presence ' wasn'4—especially ^ ,,—noticed until last week-k -J . Southwestern Ohio experienced a record, breaking delay of the traditional blanket of snow, but Wright Stafc finally got its dose of ' the white stuff last- weekend. We also had v r.ome^tuatiiuirfl cold weather this week. Thi' opinion about ttie temperature and ' snoW ap|H',ii*sto be mixed .on, campus: those • who ski like it. those who don't ski cohiplain , about hi>w miserable it Is. WWSU. Wright State's radio station, predicts tonight's temperature will fall t6 • 'between zero and five degrees. Snow, however, is'not expected. Slightly warmer temperatures arc predicted, for tomorrow, rising to about 30 degrees. KiiwaU BvGBEGMHANO i clapping rhythmically behavior. -

The Daily Egyptian, June 22, 1976

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC June 1976 Daily Egyptian 1976 6-22-1976 The aiD ly Egyptian, June 22, 1976 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_June1976 Volume 57, Issue 164 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, June 22, 1976." (Jun 1976). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1976 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in June 1976 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I . • Research continu.es. on STS ~ applications . By LeI CliudUt . ~ • that. must still be i'eview~ for e~?h being processed." One 0 .t&se is that He said the STS bill has been passed Daily Egyptian SUIf Writer apph~t. These are analysIS of stuilent the proportion qf ~plic8!lts eligible f(lr by ~ Illinois Legislature for funding ea~ amount of guar~nteed loans, STS state mafclling funds is much durIng the 19'11-77 academic year. " Assuming everything is processed redu~tJoo of ~ factors- .or those who greater than the number of students " . I . ' . on schedule, students should know the rec~lved spring STS grants and eUgible for only student contributions Whether ~tate ~atcbing money Wlll results of their summer Student-to- regIStration information. he said. ' .be made ava,llab.le 15 now,~pe~t on Student (STS) grant applications by He .said he expects to receive the Gov. Walker s s~ture , he said. July 15, " said Robert Eggertsen, registration informatioa Tuesday. "Hopefully, the students who will be EggeT~en estJ~ated that about counselor at student work and financial Funds available fe:- STS grants working as volunteers on the·STS Grant $255,~ m . -

Sydney Program Guide

6/19/2020 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_ELEVEN_Guide?psStartDate=05-Jul-20&psEndDate=11-… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 05th July 2020 06:00 am Toasted TV G Toasted TV Sunday 2020 163 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:05 am Dora The Explorer (Rpt) G Baby Bongo's Big Music Show Dora and Boots take Baby Bongo on a musical adventure as they race to the Big Music Show in time for Baby Bongo's first performance. 06:25 am Toasted TV G Toasted TV Sunday 2020 164 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:30 am Blaze And The Monster Machine (Rpt) G The Jungle Horn Stripes loves his jungle horn, a special instrument that can summon all the animals in the jungle, but when a jealous Crusher steals it, Blaze & Stripes must speed after him in a chase to get it back. 06:55 am Toasted TV G Toasted TV Sunday 2020 165 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:00 am The Bureau Of Magical Things (Rpt) CC G Forces Of Attraction Ruksy, Imogen and Lily venture into the dangerous Restricted Section of the Library in search of the truth about Kyra's new magical powers. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 3-5-1991 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (1991). The George-Anne. 1217. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/1217 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Inside Today Classifieds 7,8 Comics 8 Eagles win Faculty nicknames: What Features 3 News 2 Opinions 4 two at home you always wanted to know See Stories, page 5 Sports 5,6 See Story, page 3 Liked By Many, Cussed By Some, Geor Anne « 9127681-5246 Vol. 63, No. 33 • Tuesday, March 5 1991 Since 1927. Georgia Southern's Official Student Newspaper Georgia Southern University • Statesboro, GA 30460 News Briefs Student directories to be avertible this month ©Copyright 1991. USA TODAY/Apple ollege Information Network This year may be last year for directories because of contract disputes, selling of names contract that was signed nearly cooperate." Clark said. "Without By David G. Berny publishing company. It normally five years ago, we must fulfill our a copy, we could not negotiate." Staff Writer off of ads that they place in the takes three weeks for the agreement." said Vice President Much of the dispute was due to directories as well. -

Rick Ludwin Collection Finding

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1 Rick Ludwin Collection OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Rick Ludwin, Executive Vice President for Late-night and Primetime Series, NBC Entertainment and Miami University alumnus Media: Magnetic media, magazines, news articles, program scripts, camera-ready advertising artwork, promotional materials, photographs, books, newsletters, correspondence and realia Date Range: 1937-2017 Quantity: 12.0 linear feet Location: Manuscript shelving COLLECTION SUMMARY The majority of the Rick Ludwin Collection focuses primarily on NBC TV primetime and late- night programming beginning in the 1980s through the 1990s, with several items from more recent years, as well as a subseries devoted to The Mike Douglas Show, from the late 1970s. Items in the collection include: • magnetic and vinyl media, containing NBC broadcast programs and “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” awards compilations, etc. • program scripts, treatments, and rehearsal schedules • industry publications • national news clippings • awards program catalogs • network communications, and • camera-ready advertising copy • television production photographs Included in the collection are historical narratives of broadcast radio and television and the history of NBC, including various mergers and acquisitions over the years. 10/22/2019 Rick Ludwin Collection Page 2 Other special interests highlighted by this collection include: • Bob Hope • Johnny Carson • Jay Leno • Conan O’Brien • Jimmy Fallon • Disney • Motown • The Emmy Awards • Seinfeld • Saturday Night Live (SNL) • Carson Daly • The Mike Douglas Show • Kennedy & Co. • AM America • Miami University Studio 14 Nineteen original Seinfeld scripts are included; most of which were working copies, reflecting the use of multi-colored pages to call out draft revisions. Notably, the original pilot scripts are included, which indicate that the original title ideas for the show were Stand Up, and later The Seinfeld Chronicles. -

Old Wives' Mail: a Short Story

disClosure: A Journal of Social Theory Volume 16 Stirrings: Journeys Through Emotion Article 5 4-15-2007 Old Wives' Mail: A Short Story Trudy Lewis St. Lawrence University DOI: https://doi.org/10.13023/disclosure.16.05 Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/disclosure Part of the English Language and Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Lewis, Trudy (2007) "Old Wives' Mail: A Short Story," disClosure: A Journal of Social Theory: Vol. 16 , Article 5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.13023/disclosure.16.05 Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/disclosure/vol16/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by disClosure: A Journal of Social Theory. Questions about the journal can be sent to [email protected] Trudy Lewis Old Wives' Mail: a short story Carol brought in the mail-- always-- and this was just one of the many tasks Doug inherited when she died of a brain aneurysm in mid September in the sixth year of their marriage, no warning, just one day she was cutting up a pear for their son's breakfast as Doug left for work, her feet bare and her faded blue underpants showing beneath a stretched-out T-shirt, and the next time he saw her she was lying on a hospital stretcher, her hair still wet from her morning shower, her shredded nylons twisted around her skinned but shapely calves, a broken string of pink spit slung across her half made-up face. -

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1 Rick Ludwin Collection OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Rick Ludwin, Executive Vice President for Late-night and Primetime Series, NBC Entertainment and Miami University alumnus Media: Magnetic media, magazines, news articles, program scripts, camera-ready advertising artwork, promotional materials, newsletters, correspondence and realia Date Range: 1937-2011 Quantity: 9.0 linear feet Location: Manuscript shelving COLLECTION SUMMARY The majority of the Rick Ludwin Collection focuses primarily on NBC TV primetime and late- night programming beginning in the 1980s through the 1990s, with several items from more recent years, as well as a subseries devoted to The Mike Douglas Show, from the late 1970s. Items in the collection include: magnetic and vinyl media, containing NBC broadcast programs and “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” awards compilations program scripts, treatments, and rehearsal schedules industry publications national news clippings awards program catalogs network communications, and camera-ready advertising copy Included in the collection are historical narratives of broadcast radio and television and the history of NBC, including various mergers and acquisitions over the years. 10/9/2013 Rick Ludwin Collection Page 2 Other special interests highlighted by this collection include: Bob Hope Johnny Carson Jay Leno Conan O’Brien Disney Motown The Emmy Awards Seinfeld Saturday Night Live SNL. Carson Daly The Mike Douglas Show Kennedy & Co. AM America Fifteen original Seinfeld table scripts are included; most of which were working copies, reflecting the use of multi-colored pages to call out draft revisions. Other scripts are also contained here--some for primetime, some for broadcast specials such as the landmark three- hour broadcast of SNL’S 25th Anniversary. -

1 in SEARCH of CAPTAIN ZERO Screenplay by Allan Weisbecker

1 IN SEARCH OF CAPTAIN ZERO Screenplay by Allan Weisbecker Based on his book November 1, 2003 2 BLACKNESS, THE VOID The fast lub-dub of a heartbeat… the whoosh of a planing surfboard… and now the voice of Alex… ALEX (V.O.) I need to tell you about that wave… A FANTASTIC EXPLOSION OF SWIRLING LIQUID ENERGY Becoming a figure of a man as seen through the back of wall of a wave, all emerald and abstract, the man zooming by as the wave tunnels over him and -- strangely, because there is danger here and the man should be fearful -- the heartbeat is… slowing… ALEX (V.O.)(CONT’D) …that… moment I had… inside that wave… INSIDE THE WAVE The heartbeat slows further… the shimmering blue-green cavern expanding… the man so deep inside… that space yet growing… immense… the man deeper still… ALEX’S MOMENT This is a moment out of time… a moment wherein there is no danger, no fear, because the future is an illusion… and being inside that moment and inside the miracle of a wave… This is the most beautiful thing in the world. And that swirling liquid beauty slowly becomes… the blackness of the void again… silence… …the heartbeat stops… Alex’s voice now, so clear, calm, serene… so deep within himself… ALEX (V.O.)(CONT’D) I’m… there… right now… in that moment… because… that moment… is… forever. Hold on the quiet and the blackness, then, the sound of hammering jars us and we… SMASH CUT TO 3 EXT. SUBURBIA – DAY Malls, Burger Kings, traffic.