Learning from the Aadhaar-Enabled Fertiliser Distribution System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Management Plan

ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Of GRAVEL QUARRY For Sri Devagiri. Sankar Reddy over an extent of 1.08 HA SY. No 38/2F,38/3 Pathapadu Village, Vijayawada Rural Mandal, Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh State. Submitted by P.V.SATYANARAYANA Consultant Geologist &RQP Regn.No. RQP/DMG/AP/34/2017 , Lattice, Bommasani Sadhan, 2nd floor, Gollapudi, Vijayawada-521225 Ph.No.8610692941 INTRODUCTION Sri Devagiri. Sankar Reddy has filed an application for grant of quarry lease for Gravel over an Extent of 2.67 Acres / 1.08 Hectares In Sy. No 38/2F,38/3 of Pathapadu Village, Vijayawada Rural Mandal, Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh State, for a period of 05 years was received by the Asst. Director of Mines and Geology, Vijayawada on 11-10-2018. The Assistant Director of Mines and Geology, Vijayawada has made proposals on application filed by Sri Devagiri Sankar Reddy duly recommending for grant of Quarry lease for Gravel Over An Extent of 2.67 Acres In Sy. No 38/2F,38/3 of Pathapadu Village, Vijayawada Rural Mandal, Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh State, for a period of 05 years. After careful examination of the proposals of the Assistant Director of Mines and Geology, Vijayawada, it is agreed in principal to grant of Quarry Lease for Gravel Over An Extent of 2.67 AcresIn Sy. No 38/2F, 38/3 of Pathapadu Village, Vijayawada Rural Mandal, Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh State, for a period of 05 years in favour of Sri Devagiri. Sankar Reddy subject to submission of approved mining Plan as required under Rule 7A (i) of APMMC Rules, 1966. -

2019071371.Pdf

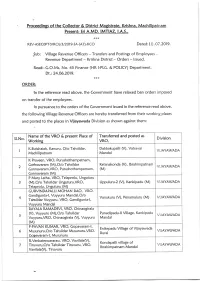

.:€ ' Proceedings of the Collector & District Magistrate. Krishna, Machilipatnam Present: Sri A.MD. lMTlAZ, 1.A.5.. >kJ.* REV-A5ECoPT(VRO)/3 /2o1s-sA-(A7)-KCo Dated: l0 .07.2019. Sub: Village Revenue Officers - Transfers and Postings of Employees - Revenue Department - Krishna District - Orders - lssued. Read:- 6.O.Ms, No. 45 Finance (HR l-P16. & POLICY) Department, Dt.:24.06.2019. ,( :k )k ORDER: {n the reference read above, the Government have relaxed ban orders imposed on transfer of the employees. ln pursuance to the orders of the Government issued in the reference read above, the following Village Revenue Officers are hereby transferred from their working places and posted to the places in Vijayawada Division as shown against them: :' Name of the VRO & present Place of Transferred and posted as 5l.No. Division Working VRO, K.Butchaiah, Kanuru, O/o Tahsildar, Dabbakupalli (V), Vatsavai I VIJAYAWADA Machilipatnam Mandal K Praveen, VRO, Purushothampatnam, 6arlnavaram (M),O/o Tahsildar Ketanakonda (V), lbrahimpatnam 2 VIJAYAWADA Gannavaram,VRO, Purushothampatnam, (M) Gannavaram (M) P Mary Latha, VRO, Telaprolu, Unguturu 3 (M),O/o Tahsildar Unguturu,VRO, Uppuluru-2 (V), Kankipadu (M) VIJAYAWADA Telaprolu, Unguturu (M) GURVINDAPALLI MOHAN RAO, VRO, 6andigunta-1, Vuyyuru Mandal,O/o 4 Vanukuru (V), Penamaluru (M) VIJAYAWADA TaLxildar Vuyyuru, VRO, Gandigunta-1, Vuwuru Mandal RAYALA RAMADEVI, VRO, Chinaogirala (V), Vuyyuru (M),O/o Tahsildar Punadipadu-ll Village, Kankipadu 5 VIJAYAWADA Vuyyuru,VRO, Chinaogirala (V), Vuyyuru Mandal (M) P-PAVAN KUMAR, VRO, Gopavaram-|, Enikepadu Village of Vijayawada 6 Musunuru,O/o Tahsildar Musunuru,VRO, VIJAYAWADA Rural Gopavaram-|, Musunuru VRO, Vavi lala (V), R.Venkateswararao, Kondapallivillage of 7 Tiruvuru,O/o Tahsildar Tiruvuru, VRO, VIJAYAWADA lbrahimpatnam Mandal Vavilala(V), Tiruvuru M.fhantibabu, VRO, Pamidimukkala,O/o Northvalluru I of Thotlavalluru 8 Tahsildar Pamidimukkala.VRO. -

Not Applicable for IOC/HPC

APPOINTMENT OF RETAIL OUTLET DEALERSHIPS IN AP BY IOC Location Sl. Name Of Location Revenue District Type of RO Estimated Category Type of Site Minimum Minimum Minimum Estimated Estimated Mode of Fixed Fee / Security No. (Not (Regular/Rur monthly (CC/DC/CFS) Frontage of Depth of Site Area of site working fund selection Min bid Deposit ( Rs applicable al) Sales Site (in M) (in M) (in Sq. M.). capital required for (Draw of amount ( Rs in Lakhs) for IOC/HPC) Potential requirement developmen Lots/Bidding in Lakhs) (MS+HSD) in for t of ) Kls operation of infrastructur RO (Rs in e at RO (Rs Lakhs) in Lakhs ) DRAW OF 1 BUKKAPATNAM VILLAGE & MANDAL ANANTAPUR Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 LOTS DRAW OF 2 GOTLUR VILLAGE, DHARMAVARAM MANDAL ANANTAPUR Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 LOTS DRAW OF 3 VAYALPADU (NOT ON NH - SH), VAYALAPADU MANDAL CHITTOOR Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 LOTS THONDAVADA VILLAGE (NOT ON NH/SH), CHANDRAGIRI DRAW OF 4 CHITTOOR Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 MANDAL LOTS DRAW OF 5 DODDIPALLE (NOT ON NH/SH), PILERU MANDAL CHITTOOR Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 LOTS NARAYANA NELLORE VILLAGE (NOT ON SH/NH) NANDALUR DRAW OF 6 KADAPA Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 MANDAL LOTS DRAW OF 7 ARAKATAVEMULA NOT ON SH/NH , RAJUPALEM MANDAL KADAPA Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 LOTS DRAW OF 8 GUTTURU VILLAGE, PENUKONDA MANDAL ANANTAPUR Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 LOTS DRAW OF 9 MADDALACHERUVU VILLAGE, KANAGANAPALLE MANDAL ANANTAPUR Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 LOTS DRAW OF 10 KALICHERLA (NOT ON NH/SH), PEDDAMANDYAM MANDAL CHITTOOR Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 LOTS CHINNACHEPALLE, NOT ON SH/ NH, KAMALAPURAM DRAW OF 11 KADAPA Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 MANDAL LOTS DRAW OF 12 GUDIPADU NOT ON SH/NH, DUVVUR MANDAL KADAPA Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 LOTS BUGGANIPALLE VILLAGE NOT ON NH/SH, BETHAMCHERLA DRAW OF 13 KURNOOL Rural 48 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 MANDAL LOTS DRAW OF 14 GOVINDPALLE VILLAGE NOT ON NH/SH, SIRVEL MANDAL KURNOOL Rural 48 ST CFS 20 20 400 0 0 0 2 LOTS DRAW OF 15 POLAKAL VILLAGE NOT ON NH/SH, C . -

Krishna District

Krishna district S.No. Name of the Health care facility 1. APSRTC Hospital, RTC Colony, Vidhyadharapuram, Vijayawada, Krishna District 2. South Central Railway, Health Unit, Opp. Railway Station, Gudivada, Krishna Dist. 3. Sub Divisional Railway Hospital, South Central Railway, Wagon Workshop, Rainapadu, Krishna District 4. Health Unit, South Central Railway, Satyanarayanapuram, Vijayawada. 5. Primary Health Centre, Rudrapaka (V), Nandivada (M), Krishna District 6. Primary Heal th Centre, Pedatummidi, Bantumilli (M), Krishna District 7. Primary Health Centre, Back of Sai Baba Temple, Velagaleru (V), G.Konduru (M), Krishna District 8. Primary Health Centre, Agiripalli, Agiripalli (M), Krishna District 9. Primary Health Centre, Mandavalli (V), Mandavalli (M), Krishna District 10. Primary Health Centre, Mallavolu (V), Guduru (M), Krishna District 11. Primary Health Centre, Zemigolvepalli (V), Pamarru (M), Krishna District 12. Primary Health Centre, Nidumolu (V), Movva (M) Krishna Distri ct 13. Primary Health Centre, Pamarru (V & M), Krishna District 14. Primary Health Centre, Kalidindi (V & M), Krishna District 15. Primary Health Centre, Pedakallepalli (V), Mopidevi (M), Krishna District 16. Primary Health Centre, Ghantasala (V & M), Krishna District 17. Primary Health Centre, Chinapandraka (V), Kruthivenu (M), Krishna District 18. Primary Health Centre, Mandapakala (V), Koduru (M), Krishna District 19. Primary Health Centre, Seethanapalli(V), Kaikaluru (M), Krishna District 20. Primary Health Centre, Nimmakuru (V), Pamarru (M) Krishna District 21. Primary Health Centre, Ghantasalapalem (V), Ghantasala (M), Krishna District 22. Primary Health Centre, Puritigadda (V), Challapalli (M), Krishna District 23. Primary Health Centre, Peda avutapalle (V), Unguturu (M) Krishna District 24. Primary Health Centre, Pendyala (V), Kanchikacherla (M) Krishna District 25. Primary Health Centre, Mopidevi (V & M), Krishna District 26. -

Analysis of Corrosion Rates of Mild Steel, Copper and Aluminium in Underground Water Samples of Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh, India

International Journal of Advance Research In Science And Engineering http://www.ijarse.com IJARSE, Vol. No.3, Issue No.12, December 2014 ISSN-2319-8354(E) ANALYSIS OF CORROSION RATES OF MILD STEEL, COPPER AND ALUMINIUM IN UNDERGROUND WATER SAMPLES OF KRISHNA DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH, INDIA V. Rajesh1, C. L. Monica2, D. Sarada Kalyani3, S. Srinivasa Rao4 1,2,3,4 Department of Chemistry, V. R. Siddhartha Engineering College (Autonomous), Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh, (India) ABSTRACT A few underground water samples are collected from various mandals located adjacent to Krishna river in Krishna district of Andhra Pradesh, India. The quality parameters of water samples are determined using volumetric and instrumental methods. The parameters determined include chloride content, hardness, alkalinity, dissolved oxygen, total dissolved solids, total suspended solids, pH and conductivity. Corrosion rates of commercially important metals viz., mild steel, copper and aluminium are determined in all the collected water samples using conventional gravimetric measurements. An attempt is made to correlate the water quality parameters with the corrosion rates of metals. A clear correlation was observed in case of majority of water samples with reference to certain parameters like pH, conductivity and chlorides which have a direct impact on corrosion rate of a metal. Keywords: Commercial Metals, Corrosion Tendencies, Krishna District, Underground Water Samples, Water Quality Parameters I. INTRODUCTION Metals like carbon steel, copper, aluminium, etc. are commercially much significant due to their use in various engineering and construction fields due to their better mechanical, physical and chemical properties. However, these metals exhibit high susceptibility to corrosion in environments in which they are expected to work. -

Government of Andhra Pradesh Directorate of Institute of Preventive Medicine, Ph Labs, Food (Health) Admn, Narayanaguda, Hyderabad

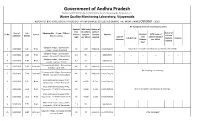

GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH DIRECTORATE OF INSTITUTE OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, PH LABS, FOOD (HEALTH) ADMN, NARAYANAGUDA, HYDERABAD REPORT OF BACTERIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF WATER SAMPLES (COLLECTED DURING MONITORING) July 2012 Name of the Laboratory: WATER QUALITY MONITORING LABORATORY, VIJAYAWADA Sl. Date of Lab source Municipality/Town/ Residual MPN Nature R Re-sampling result of unsatisfactory points index of e No. collection Ref Village chlorine of Coli MPN coli form m Date of Lab Resid Nature of re No. Exact Location mg/l form index of Coli form bacteria a collecti Ref ual coli form m per 100 Bacteria r on No. Chlor Bacteria Bacteria ar ml isolated k ine per 100 ml isolated ks s mg/l 1 1-07-12 2417 Pond Tap at srinivasa nursing 0.2 Nil -------- Sat -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --- house kalidindi village and --- -- mandal 2 1-07-12 2418 Pond Tap at PHC hospital 0.2 Nil -------- Sat -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- kalidindi V & M 3 1-07-12 2425 Pond Tap at SC colony end 0.2 Nil --------- Sat point, Venkatapuram (V) -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- Kalidindi mandal 4 2-07-12 2441 Pond Medical officer, PHC, Nil >1609 Klebsiella US Moturu, Gudivada These samples are collected by DM & HO staff rural,Sample from and informed to carried out re-sampling after taking Kothachoutapalli near corrective actions MPP school Gudivada rural 5 2-07-12 2443 Munici Indulge restaurant Pvt ltd, 2.0 Nil --------- Sat pal Plot No:44,CTO Colony -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- water near Gurunanak nagar Vijayawada, -

Environmental Management Plan

ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Ordinary River Sand Mine, Madduru Village, Kankipadu Mandal, Krishna District,Andhra Pradesh Environmental Management Plan Introduction 1.1 Background In a developmental activity like Ordinary sand mining, all the exercise must co-exist satisfactorily with its surrounding condition so as to minimize the adverse impact on the environment. To control the likely adverse impacts and to achieve this goal, it is necessary to prepare a sound and Environmental Management Plan, which has to be implemented by the proponents, in order to achieve environmental protection along with production profits. Government of Andhra Pradesh proposes to give specified sand bearing area for ordinary sand by way of allotment of the specified sand bearing area by draw of lots over an extent of 2.590 hectares of Madduru village, Kankipadu Mandal, Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh. The proposal is submitted for environmental clearance as per the Minor Mineral Concession Rules issued by Industries & Commerce (Mines-1) Department, Government of Andhra Pradesh vide G. O. Ms. No. 154 dated 15- 11-2012 and APWALT Act '2002. Asst. Director of Mines and Geology, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh, Vijayawada, Krishna District has filed an application for quarry lease for Ordinary Sand mine over an extent of 2.590 hectares of Madduru village, Kankipadu Mandal, Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh to the Assistant Director of Mines and Geology. 1.2 Project proponent Asst. Director of Mines and Geology, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh, Vijayawada, Krishna District has been granted quarry lease for mining of ordinary sand over an extent of 2.590 hectares of Madduru village, Kankipadu Mandal, Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh. -

2014 Date of Sl

LIST SHOWING THE DETAILS OF BUILDING APPROVALS 2014 Date of Sl. Location with Extent of Mortgage B.P.No File No. Name of the owner & address No.of floors approva No. R.S.No. site particulars . l Sri Musunuru Durga Prasad, Stilt, Ground+4 upper S/o.Seetharamaiah, Door No.6- 68/1A of 9484.95 floors Apartment in 6138/2013 1 C2-2672/13 41, Poranki Village road, Nidamanuru 22.01.14 01/14 Sq.m. Block No.1 & 2 Hostel & dt.27.12.2013 Nidamanuru Village, Vijayawara Village Warden Quarters buildings Rural Mandal, Krishna District Sri K.Bhargav, S/o.Prasad, Door 550/1A of Stilt for parking+4 upper 8142/2013 2 C5-2426/13 397.16 Sq.m. 04.01.14 02/14 No.5-62, Gollapudi Gollapudi floors Apartment dt.11.12.2013 Sri M.Kiran Kumar, S/o.Venkateswara Rao, Door 3 C8-2679/13 Kanuru 138.51 Sq.m Ground & First floor 07.01.14 03/14 No.15-26-145, K.V.H.Colony, Hyderabad Sri Myneni Krishna Mohan, S/o.(late) Venkata Rao, Door Stilt for parking+4 upper 7810/2013 4 C8-3906/12 No.40-16-6, Siddardha Mahila 287/2 of Kanuru 398.84 Sq.m. 24.01.14 04/14 floors Apartment dt.04.12.2013 College Road, Labbipet, Vijayawada-10 Smt. K.Radharani, W/o.Ramu, 115/6 of 1537.86 Flat Form for Fly Ash .10.01.1 5 C2-2774/13 R.S.No.115/6, Chopparametla 05/14 Chopparametla Sq.m. Bricks 4 Village, Agiripalli Mandal Sri Ramesh Kumar & others, 5 & 6 of 2950.30 Stilt+4 upper floors 6 C5-2500/13 21.01.14 06/14 Gollapudi Gollapudi Sq.m. -

The Following Candidates Are Requested to Attend Interviews On

1 The following candidates are requested to attend interviews on 28.10.2017 at 09.00 AM at Nyaya Seva Sadan, District Court Complex, Machilipatnam with all original certificates for selection of PLVs in Krishna District. Mobile Educational Sl. No. Name of the Candidate & Address Present Profession Remarks Number Qualifications Bollu Srinivas, S/o. Late Veeranjaneyulu, D.No.14/324-2, Edepalli, 1 9032417808 S.S.C Near Jodugullu, Mallayya Sweets shop, Machilipatnam Working as member of Dasari Vijayalakshmi, D/o. D.V. Subbaiah, 21/400, Bhaskarapuram, Retd., Deputy 2 8008523154 B.Sc.,B.Ed., Family Welfare Machilipatnam-521001 Eductional Officer Committee Ch. Tarundeep, S/o. Phanibabu, D.No.14-19-1, Near UTF Building, 3 9908864295 10th class Machilipatnam, Krishna District Modugumudi Asha, D/o. Modugumudi Sivaiah, D.No.16/31-12, Fish 4 812573.4081 10th class Market, Pedana, Krishna District Seelam Bala Tripura Sundari, W/o.Rma Mohana Rao, D.No.19/565, 5 8125827395 B.A Tailoring work Circarthota, Machilipatnam. Dokku Indira , D/o. Edukondalu, D.No.21-178, Guduru Village and 6 9553407409 10th class - - Mandal, Krishna Dt. Chalamalasetti Adilakshmi, W/o. Venkateswar Rao, Near Madhava 8790742400 7 10th class Swamy Temple, Guduru Village and Mandal 8688136465 Palli Narendra, S/o. Palli Yedukondalu, SC Boys Hostel No.1 A, Near P.G 8 9652927964 Railway Station, Machilipatnam (Studying) Kunaparreddy Sivasai, S/o.Durga Nageswara Rao, D.No.4/414, 9 8142532903 10th class Rajupet, Machilipatnam. 2 Mobile Educational Sl. No. Name of the Candidate & Address Present Profession Remarks Number Qualifications Saladi Siva Prasad, S/o. -

Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority Act, 2014 - Declaration of A.P

GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH ABSTRACT Municipal Administration & Urban Development Department - Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority Act, 2014 - Declaration of A.P. Capital Region – Orders - Issued. MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATION & URBAN DEVELOPMENT (M2) DEPARTMENT G.O.MS.No. 253 Dated: 30.12.2014 Read the following: 1. Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority Act, 2014 (Act.No.11 of 2014 ) 2. G.O.Ms.No.252, MA&UD Dept., Dated:30.12.2014 ***** ORDER: The Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority Act, 2014 has come into force with effect from 30th day of December, 2014 by virtue of notification published in the Extra-ordinary issue Andhra Pradesh Gazette, dated: 30.12.2014. 2. The Government have consulted experts in urban development and various public organizations with regard to appropriate location of capital city. The Government have also considered various aspects of location of the capital keeping in view welfare of the state population, administrative efficiency and accessibility to all corners of the state. 3. The Government in exercise of the powers under sub section 1 of Section 3 of Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority Act, 2014 hereby notify the areas covering broadly an area of about 7068 Sq. Kms as detailed in the schedule to the notification appended here to, as Andhra Pradesh Capital Region which is meant for development under the provisions of the Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority Act-2014. 4. The appended notification shall be published in the Extra-ordinary issue of Andhra Pradesh Gazette dated: 30.12.2014. The Commissioner, Printing, Stationery & Stores Purchase, Hyderabad is requested to arrange to publish the said notification accordingly and furnish 150 copies of the notification to the Government. -

Bacteriological Report Vijayawada October

Government of Andhra Pradesh Directorate of I.P.M.P.H.Labs, Food (H) Administration, Narayanaguda, Hyderabad - 29 , Water Quality Monitoring Laboratory, Vijayawada REPORT OF BACTERIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF WATER SAMPLES (COLLECTED DURING THE MONITORING) October - 2013 Re- Sampling results of unsatisfactory points Residual MPN index Nature of free of coliform coliform Date of Lab Municipality / Town / Village/ Nature of Sl. No: Source chlorine bacteria bacteria Remarks Residual MPN index of collection Ref.NO Exact location coliform mg/l per 100 ml isolated Date of Free coliform bacteria Lab Ref. No: bacteria remarks collection Chlorine per 100 ml isolated mg/l Balliparru village , Gannavaram 1 1/10/2013 5137 River Nil 240 Klebsiella unsatisfactory because of raw water not necessary to recollect the sample mandal , sample from tank Balliparru village , Gannavaram 2 1/10/2013 5142 River 0.2 Nil …. Satisfactory …. …. …. …. …. …. mandal , tap near SC Colony Bazar Balliparru village , Gannavaram 3 1/10/2013 5143 River 0.2 nil ….. Satisfactory …. …. …. …. …. …. mandal , tap opp. Church Chinnaautupalli village , Gannavaram 4 1/10/2013 5145 Bore well Nil 43 Klebsiella unsatisfactory Mandal , tap at tank Re sampling not necessary Chinnaautupalli village , Gannavaram 5 1/10/2013 5146 Bore well Nil 39 Klebsiella unsatisfactory Mandal , tap near Primary school Head water works campus VMC, 6 1/10/2013 5151 River Nil >1609 E.Coli unsatisfactory Vijayawada , 11 MGD Raw water Head water works campus VMC, 7 1/10/2013 5152 River Vijayawada , 11 MGD Clarifier water - Nil >1609 E.Coli unsatisfactory As it is raw water not necessary to resample I Head water works campus VMC, 8 1/10/2013 5153 River Vijayawada , 11 MGD Clarifier water - Nil >1609 E.Coli unsatisfactory II Head water works campus VMC, 9 1/10/2013 5154 River 2..0 Nil … Satisfactory …. -

Hand Book of Statistics 2014 Krishna District

HAND BOOK OF STATISTICS 2014 KRISHNA DISTRICT Compiled by Chief Planning Officer Krishna, Machilipatnam Sri BABU.A, I.A.S., Collector & District Magistrate Krishna District P R E F A C E I am glad that the Hand Book of Statistics 2014 of Krishna District with statistical data of various departments for the year 2013-14 is being released. The statistical data in respect of various schemes being implemented by the departments in the district are compiled in a systematic manner so as to reflect the progress made under various sectors during the year. The sector wise progress is depicted in sector – wise tables apart from Mandal - wise data. I am confident that the publication will be of immense utility as a reference book to general public and Government and Non-Governmental agencies in general as well as Administrators, Planners, Research Scholars, Funding agencies, Banks and Non-Profit Institutions. I am thankful to all the District Officers and the Heads of Institutions for extending their co-operation by furnishing the information to this Hand Book. I appreciate the efforts made by Sri K.V.K.Ratna Babu, Chief Planning Officer, Krishna District and their Staff in collection and compilation of data in bringing out this publication. Any suggestions aimed at improvement of Hand Book are most welcome and may be sent to the Chief Planning Officer, Krishna District at Machilipatnam Date: 31.12.2015. Station: Machilipatnam OFFICERS AND STAFF ASSOCIATED WITH THE PUBLICATION 1. Sri K.V.K.Ratna Babu : Chief Planning Officer 2. Sri D.Venkateswarlu : Deputy Director 3.