A Study Into the Material Culture of the Morgan Family of Tredegar House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belton Setting Study

Belton House and Park Setting Study and Policy Development South Kesteven District Council and National Trust January 2010 Belton House and Park Setting Study and Policy Development Final 10.01.10 Notice This report was produced by Atkins Ltd for South Kesteven District Council and The National Trust for the specific purpose of supporting the development of policy for the setting of Belton House and Park. This report may not be used by any person other than South Kesteven District Council and The National Trust without South Kesteven District Council’s and The National Trust’s express permission. In any event, Atkins accepts no liability for any costs, liabilities or losses arising as a result of the use of or reliance upon the contents of this report by any person other than South Kesteven District Council and The National Trust. Document History JOB NUMBER: 50780778 DOCUMENT REF: Belton Final September 2009 (revised).doc 4 Final (typographic KS/JB/CF KS AC AC 10/01/10 corrections) 3 Final KS/JB/CF KS AC AC 29/09/09 2 Final Draft KS/JB/CF KS AC AC 17/6/09 1 1st full draft for client KS/JB/CF KS AC AC 3/4/09 discussion Revision Purpose Description Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date 50780778/Belton Final Final Jan 2010 (revised).doc Contents Section Page 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Purpose & Scope of the Study 4 1.2 The National Trust Belton House Estate 4 1.3 Structure of the Report 4 1.4 Method 5 1.5 Planning Background 6 2. -

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Afghanistan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 2 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 3 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 24 Culture Gram .......................................................... 30 Kazakhstan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 39 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 40 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 58 Culture Gram .......................................................... 62 Uzbekistan ................................................................. CIA Summary ......................................................... 67 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 68 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 86 Culture Gram .......................................................... 89 Tajikistan .................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 99 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 117 Culture Gram .......................................................... 121 AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT ECONOMY Chief of State Economic Overview President of the Islamic Republic of recovering -

2019 Nmhc Spring Board of Directors Meeting

7:45 – 8:15 a.m. Breakfast Social 2019 SPRING BOARD OF DIRECTORS Location: Grand Ballroom Pre-Function, 8th Floor MEETING SPONSORS 8:15 – 11:45 a.m. General Session Location: Grand Ballroom, 8th Floor • Business Meeting • The Good, The Bad and The Ugly of Doing Business in Chicago MODERATOR: David Schwartz, CEO, Chairman and Co-Founder, Waterton SPEAKERS: 2019 NMHC SPRING BOARD John Jaeger, Executive Vice President, CBRE Greg Mutz, Chairman and CEO, AMLI Residential OF DIRECTORS MEETING Partners, LLC Maury Tognarelli, Chief Executive Officer, Heitman May 15-17, 2019 Four Seasons • Chicago, IL • Finding and Nurturing Industry Talent SPEAKERS: David Payne and Debbie Phillips, Careers Building Communities website MEETING AGENDA PANEL DISCUSSION: MODERATOR: STAY CONNECTED Debbie Phillips, Principal & President, The Quadrillion SPEAKERS: Tracy Bowers, Managing Director, Property Agenda Sponsored By: Management, Pollock Shores Real Estate Group NEW! CONFERENCE APP Rob Presley, Vice President of Facilities Management, Gables Residential Download the NMHC meeting app to access Vince Toye, Head of Community Lending & all of the meeting information and network with Investment, Wells Fargo Multifamily Capital attendees. View the most up-to-date agenda, speaker bios, attendee list and more! Resilient Chicago • Search for “NMHC” in your app store and MODERATOR: download the app. Select the NMHC Spring , Senior Vice President, Heitman Helen Garrahy Board of Directors Meeting. SPEAKER: Stefan Schaffer, Chief Resilience Officer, Chicago Conference App Password: spring2019 Mayor’s Office 11:45 a.m. Meeting Adjourns Join the conversation on Twitter at #NMHCspring Note: Agenda as of May 7, 2019; subject to change. Please be aware that Wi-Fi service is available in the meeting rooms 1775 Eye St., N.W., Suite 1100, Washington, D.C. -

Let's Walk Newport: Small Walks for Small Feet

SMALL WALKS for small feet... FIND YOUR NEWPORT WALK Lets Walk Newport - Small Walks for Small Feet 10 Reasons to walk... 1. Makes you feel good 2. Reduces stress 3. Helps you sleep better 4. Reduces risk of:- • Heart disease • Stroke • High blood pressure • Diabetes • Arthritis • Osteoporosis • Certain cancers and can help with theirmanagement and recovery 5. Meet others and feel part of your community 6. See your local areaand discover new places 7. Kind to the environment 8. Can be done by almost anyone 9. No special equipment required 10. Its FREE, saving money on bus fares and petrol 2 Lets Walk Newport - Small Walks for Small Feet How often should I walk? As often as you can Aim for at least:- 30minutes This can be in one go or 3 walks of 10 minutes or 2 walks of 15 minutes per day or more days 5 of the week How fast should I walk? Start slowly to warm up gradually increase to a brisk pace:- • heart beating a little faster • breathing a little faster • feel a little warmer • leg muscles may ache a little • you should still be able to hold a conversation Slow down gradually to cool down Tips • Walk to the local shops • Get o the bus a stop earlier • Park a little further from your destination • Walk the children to and from school • Go for a lunchtime walk • Walk to post a letter • Use the stairs • Walk with friends/family • Explore new areas • Walk the dog • Note your progress 3 Lets Walk Newport - Small Walks for Small Feet What equipment will I need? Healthy Start Walks brochure:- • Comfortable and sensible footwear (no ip-ops or high heels) • Water Small Walks for Small Feet brochure:- • Comfortable and sensible footwear (no ip-ops or high heels) • Water Healthy Challenge Walks brochure:- • Sturdy footwear • Water Countryside Walks brochure:- • Sturdy footwear/Hillwalking boots • Water Safety information (Countryside brochure only) • Tell someone where you are going • Tell someone how long you will be • Remember to let them know when you return Have fun and enjoy your walk! 4 Lets Walk Newport - Small Walks for Small Feet Walks Distance Page 1. -

From: Biron, Cynthia <[email protected]> Sent

From: Biron, Cynthia <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, February 15, 2021 11:52 AM To: Friedman, Paula K <[email protected]> Subject: No short Term rentals in Brookline Dear Paula, I am writing as a concerned condominium owner and building trustee in Brookline. I am a long term owner and resident of 44 Browne Street in Coolidge Corner, in a large 50 unit building. I am very concerned about the possible changes to Brookline’s zoning by-law that will allow short term rentals in apartments. This is problematic and very concerning For a number of reasons. This allowance could disrupt the quiet enjoyment of our home with the increased activity of more people coming and going on the property. Having more and diFFerent groups oF strangers on the property will increase the cost oF shared utilities, water, trash, increased and wear and tear on the building. Safety is also a very big concern; in addition to personal safety issues, there is an increased risk oF fire and accidents, resulting in increased liability claims and expenses incurred by all owners. Other issues include a loss of a sense of community by having too many strangers coming and going, and Fewer long term residents. Also, Condominium documents are widely varied. Some associations may need to amend their documents, which would be especially challenging after legalizing Short term rentals, and without securing the high majority needed (75%) to change documents, current residents may Find themselves forced to live with Short-term rentals, fundamentally changing their home environment. Lastly, condo owners seeking a STR certificate from the Town must be required to submit a form from the Association positively consenting to the presence oF a STR. -

Listed Buildings Detailled Descriptions

Community Langstone Record No. 2903 Name Thatched Cottage Grade II Date Listed 3/3/52 Post Code Last Amended 12/19/95 Street Number Street Side Grid Ref 336900 188900 Formerly Listed As Location Located approx 2km S of Langstone village, and approx 1km N of Llanwern village. Set on the E side of the road within 2.5 acres of garden. History Cottage built in 1907 in vernacular style. Said to be by Lutyens and his assistant Oswald Milne. The house was commissioned by Lord Rhondda owner of nearby Pencoed Castle for his niece, Charlotte Haig, daughter of Earl Haig. The gardens are said to have been laid out by Gertrude Jekyll, under restoration at the time of survey (September 1995) Exterior Two storey cottage. Reed thatched roof with decorative blocked ridge. Elevations of coursed rubble with some random use of terracotta tile. "E" plan. Picturesque cottage composition, multi-paned casement windows and painted planked timber doors. Two axial ashlar chimneys, one lateral, large red brick rising from ashlar base adjoining front door with pots. Crest on lateral chimney stack adjacent to front door presumably that of the Haig family. The second chimney is constructed of coursed rubble with pots. To the left hand side of the front elevation there is a catslide roof with a small pair of casements and boarded door. Design incorporates gabled and hipped ranges and pent roof dormers. Interior Simple cottage interior, recently modernised. Planked doors to ground floor. Large "inglenook" style fireplace with oak mantle shelf to principal reception room, with simple plaster border to ceiling. -

Belton Stables

By Appointment to Her Majesty The Queen Manufacturer and Supplier of Secondary Glazing Selectaglaze Ltd. St Albans TM Secondary Glazing Belton Stables Benefit: Warmer and quieter In 2018, the National Trust began an ambitious project to conserve and rejuvenate the stables to provide Type: Conversion and Refurbishment a sustainable future for the building. Although a Listing: Grade I restaurant was installed on the ground floor as soon as the National Trust took over in 1984, the building was The Grade I Listed Belton House stable block in in serious need of an update. The plan was to restore Grantham, Lincolnshire was built in 1685 and is lauded the building sympathetically to include a new café for its artistic and historical value. It is one of just 10 significant surviving 17th century stables in England, famous for the number original features intact. The stables were built by William Stanton and form part of the Belton Estates, home of the Brownlow and Cust families for three hundred years; a dynasty of renowned lawyers. Alterations were made to the building between 1811 and 1820 for the 1st Earl of Brownlow by Jeffry Wyatt. Further upgrades were made in the 1870s when the St Pancras Iron Work Co. installed the finest loose boxes for the third Earl to house his racehorses. The whole estate was offered to the Government for war services and served as a base for the Machine Gun Corps during WW1. Belton was also home to the RAF Regiment during the Second World War. The National Trust took over the whole Belton Estate 1984 after the Brownlows were faced with mounting financial problems. -

Historic House Eg 1

Historic House Hotels Heritage Tour | ItiNerary CLASSIC CULTURE DesigNed for those who waNt to visit aNd eNjoy BritaiN's uNique heritage of beautiful couNtry houses. HISTORIC HOUSES ExperieNce the art of quiNtesseNtial couNtry house liviNg at its best, with award- wiNNiNg restauraNts, health aNd beauty spas, all situated iN beautifully laNdscaped gardeNs. NATIONAL TRUST IN 2008 BodysgalleN Hall North Wales, Hartwell House Vale of Aylesbury aNd Middlethorpe Hall York were giveN to the NATIONAL TRUST to eNsure their loNg-term protectioN. BODYSGALLEN HALL & SPA H I S T O R I C H O U S E H O T E L S - S T A Y I N H O U S E S O F CONWY CASTLE D I S T I N C PLANNING T I They are represeNtative iN their differeNt O ways of the best of graNd domestic N YOUR TRIP architecture, from the JacobeaN aNd GeorgiaN spleNdour of Hartwell House to the crisp WWW.HISTORICHOUSEHOTELS.COM precisioN of brick aNd stoNe of Middlethorpe Hall or the Welsh verNacular charm of These sample tour itiNeraries have beeN BodysgalleN Hall set oN its wooded hill-side desigNed for the pleasure of those who eNjoy both stayiNg iN aNd visitiNg part of BritaiN's uNique heritage of beautiful TRAVEL couNtry houses. SUGGESTIONS You will stay iN the order of your choice iN three carefully restored Historic House For your jourNey betweeN our houses, we have Hotels, each aN importaNt buildiNg iN its made recommeNdatioNs for visits to properties owN right, all with a spleNdid gardeN aNd that are eN-route. -

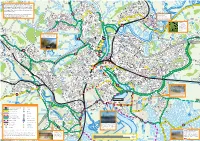

Newport Cycle Map Shows the Improving E

E C LAN A4051 RE O PE NT L LE GE A O G VE W L B E N E A 4 K O N 2 O U D R E E 3 B C 6 N L A A To L 4 GL 0 A A D E R N O 5 4 - 0 D US R 1 L K C Cwmbran 4 E D H C I VE 2 F L I A O W R H E R L W T L A R I O D Y E O F A G N C T D R The Newport Cycle Map shows the improving E SO L N S D A G L E T A A D R R LD CL E P BE E FIE IV E RO H O M G R W I L D N O H M E C E network of ‘on’ and ‘off’ road routes for cycling. Be A S N S C T R O V L A ER O T O R E L H L ND SN S E A L C Y A CL D A E C E I L L A C S N W R P L L E O E T K P L R D A N ROO E L Y L A B R E A D N IE C it for getting to work, leisure or as a way to enjoy C L F O K G O N R S ESTFIELD IE H R DO CL G I F A A A HAR W H T L A B R L C R D N R E O IN E Y D DR G C A L F G S I A A R L O O T T AV T H I W E C F N N A L I I H W E D the heritage, attractions, city county or countryside L E L CL A V A A I RI D V D WAY E P A O H E D R H WHITTL E VI E D R L B M P R D C R A I D L S R L BAC D A N O O E IE L N F E N D W M I E of Newport. -

Short-Term Rental Tax Rate Chart by State

State Short-Term Rental Tax Rate Chart – November 20181 Maximum State Rate (%) Comments Source Alabama 5.00% Owner/Operator Ala. Code § 40-26-1- (2018); Ala. Admin. Code A lodgings tax of 5.0 % is imposed in the 16-county Alabama mountain lakes r. 810-6-5-.13, .22 (2018) area. The rate in all other Alabama counties is 4.0%. The lodgings tax applies to all charges made for the use of rooms, lodgings, or other accommodations, including charges for personal property used or services furnished in the accommodations, by every person who is engaged in the business of furnishing accommodations to transients for less than 180 continuous days. The lodgings tax is due and payable in monthly installments on or before the twentieth day of the month following the month in which the tax accrues. Municipal and county lodging taxes may also apply. Ala. Dep’t Rev., Sales and Use Tax Rates (last visited Oct. 11, 2018) (search for specific local rates here) Facilitator Alabama does not require marketplace facilitators to collect lodging taxes on behalf of their hosts. However, facilitators may voluntarily collect those taxes. 1 The indicated rates reflect the amount of taxes imposed on a short-term rental on a statewide basis. A variety of local option taxes of varying amounts also apply in nearly all states. Information regarding local taxes and rates is available on state revenue/tax department websites. Note that local taxes are subject to frequent change. In some jurisdictions where there are no provisions specifically governing marketplace facilitators, such as Airbnb or VRBO, the facilitators have voluntarily entered into tax collecting agreements with the state and/or local governmental taxing authorities. -

DELTA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT's CABINET Minutes

DELTA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT’S CABINET Minutes Meeting date: October 27, 2014 Members in attendance: President William LaForge, Dr. Wayne Blansett, Dr. David Hebert, Dr. Debbie Heslep, Mr. Ronnie Mayers, Dr. Charles McAdams, Dr. Michelle Roberts, Mr. Jeff Slagell, Mr. Mikel Sykes, Dr. Myrtis Tabb, and Ms. Leigh Emerson. Members not in attendance: Mr. Keith Fulcher, Mr. Steve McClellan, and Ms. Marilyn Read Call to Order: A regular meeting of the President’s Cabinet was held in the President’s Conference Room on October 27, 2014. The meeting convened at 1:30 p.m. with President LaForge presiding. GENERAL OVERVIEW: President LaForge displayed copies of the Delta State ads and articles that were in recent editions of the Bolivar Commercial and Clarion Ledger. President LaForge presented Mr. Ronnie Mayers with certificates to give to the students who won the Halbrook Awards. President LaForge announced that he had good visits with Lewisburg High School and DeSoto Central last week. He also attended a social that the recruiters held for all the high school seniors in the area. It was the first time they have done this. Dr. Heslep said it was a good event, and she took lots of notes of ways they could improve it next time. President LaForge had a conversation with a past university president, who is associated with the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU), to discuss how we could revamp the four student service offices on the first floor of Kent Wyatt Hall. The Executive Committee will discuss some ideas and will bring them back to Cabinet for discussion. -

Master Fee Schedule

Effective August 2, 2021 FEE SCHEDULE (With Developer Deposit Schedule) Master Fee Resolution No. 8672 (Fees as amended through August 2, 2021) 1 Effective August 2, 2021 City of Fremont MASTER FEE RESOLUTION Resolution No. 8672 (Fees as amended through August 2, 2021) I N D E X Page I. GENERAL AND MISCELLANEOUS ............................................................................................ 4 A. City of Fremont Municipal Code ............................................................................................ 4 B. Special Event Permits ........................................................................................................... 4 C. Special Event Staff Charges ................................................................................................. 4 D. Business Tax ......................................................................................................................... 4 E. Recovery of Legal Costs in Lawsuits..................................................................................... 4 F. Certificates of Compliance – Public Transportation .............................................................. 4 G. Labor Cost for Employees ..................................................................................................... 4 H. Development Services Billing Process .................................................................................. 5 I. Document Certification .........................................................................................................