Gatineau Park: a Case Study of Managing Recreation in the Wildland-Urban Interface

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2016

January 2016 The Canadian Arab Community in Ottawa-Gatineau The 9th in a series analyzing the 2011 census data released by Statistics Canada, this report shows the profile of the Canadian Arab population residing in Ottawa-Gatineau. Ghina Dajani 1 Ottawa-Gatineau’s Canadian Arab community – a visible minority Percentage of self-identified Canadian Arabs residing in Ottawa-Gatineau Canadian Arabs in Ottawa-Gatineau Canadian Arabs in the rest of Canada Ottawa-Gatineau’s Canadian Arab community is the third largest population gathering of Canadian Arabs in a Canadian city, accounting for 10% of the total population of Canadian Arabs in Canada (72,960 of 750,925 Canadian Arabs). Furthermore, the Canadian Arab community constitutes 6% of the total population in Ottawa-Gatineau. Total population of self-identified Canadian Arab communities in Ottawa-Gatineau 30,000 25,000 20,000 15,000 10,000 5,000 0 Iraq Arab Syria Egypt Berber Algeria Somalia Morocco Lebanon Palestine 2 Religion, Marital Status, and Family Status of Ottawa-Gatineau’s Canadian Arab community Total population of Canadian Arabs in Ottawa-Gatineau by selected Religions Muslims Christian No religious affliation Jewish When it comes to religious affiliation, the make-up of the Canadian Arab community in Ottawa-Gatineau reflects the community’s national trend – with those of the Muslim faith constituting a majority (59%) followed by Christians (34%). Total population of Canadian Arabs Total population in in Ottawa-Gatineau aged 15 years Ottawa-Gatineau aged 15 years and over by Maritial Status and over by Maritial Status Married (and not seperated) Living common law Married (and not seperated) Living common law Single (never legally married) Seperated Single (never legally married) Seperated Divorced Widowed Divorced Widowed 3 The Canadian Arab community in Ottawa-Gatineau falls within a similar break-down of marital status as that of the national Canadian Arab community, and is also quite similar to the city’s general marital status profile. -

Language Contact and Mixing in Ottawa and Gatineau in 2011 Jack

Language Contact and Mixing in Ottawa and Gatineau in 2011 Jack Jedwab November 2012 1. Introduction Recently released results of the 2011 census on language identification, language knowledge and home use revealed little change in the distribution of language groups in the National Capital Region since the 2006 census. This despite concerns that change in census context may give rise to problems in intecensal comparisons. Yet little change on some dimensions of language identification and knowledge should not be seen as good news. The table below looks at the percentage shift in population on the basis of mother tongue in the NCR and perhaps the point most worthy of interest is the rise in the percentage of mixed responses. In real number the mixed responses rose from 20 805 to 35 075 between 2006 and 2011 and English/French mixed responses from 10 500 to 16 665 over that same period for an increase of nearly 60%. Although the numbers may seem small they nonetheless reflect a census trend that is in part explained by more comfort in acknowledging dual language identity in a context where language policy analysts have often encouraged respondents to think in singular terms (you’re either an anglophone, francophone or other). Indeed despite the rise in the percentage reporting the first language they learned was both English and French), it is likely that this grossly under represents the percentage that identify with two languages. Indeed the 2011 census reveals that in the NCR some 53 195 speak both French and English most often at home, 81 440 people speaking French most often in their homes also to some degree report speaking English and 69 715 NCR anglophones report speaking some French at home. -

Sixth Interprovincial Crossing Refresh

NATIONAL CAPITAL COMMISSION SIXTH INTERPROVINCIAL BRIDGE CROSSING STUDY REFRESH Summary Report SIXTH INTERPROVINCIAL BRIDGE CROSSING STUDY REFRESH Summary Report NATIONAL CAPITAL COMMISSION V5 PROJECT NO.: 19M-01103-00 DATE: APRIL 8, 2020 WSP SUITE 300 2611 QUEENSVIEW DRIVE OTTAWA, ON, CANADA K2B 8K2 T: +1 613 829-2800 F: +1 613 829-8299 WSP.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1 1.1 Background ........................................................................ 2 2 NOISE & VIBRATION REPORT .......................... 3 2.1 Conclusions from Previous Report ................................. 3 2.2 Methodology for Refresh .................................................. 4 2.3 What has Changed ............................................................ 5 2.4 Potential Impacts Due to Change .................................... 5 3 LAND USE AND PROPERTY REPORT ............. 6 3.1 Conclusions from Previous Report ................................. 6 3.2 Methodology for Refresh .................................................. 6 3.3 What has Changed ............................................................ 7 3.4 Potential Impacts Due to Change .................................... 8 4 AIR QUALITY REPORT .................................... 10 4.1 Conclusions From Previous Report .............................. 10 4.2 Methodology for Refresh ................................................ 10 4.3 What has Changed .......................................................... 10 4.4 Potential -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Embassy of the United States of America 490 Sussex Drive Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1N 1G8

Embassy of the United States of America 490 Sussex Drive Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1N 1G8 LIST OF ATTORNEYS AND TAX SERVICES FOR THE OTTAWA CONSULAR DISTRICT 2018 The consular district of the Embassy in Ottawa comprises a number of counties located in the eastern portion of Ontario and the western portion of Quebec (i.e., the counties of Lanark, Leeds, Prescott, Renfrew, Russell, and Stormont in the Province of Ontario, and the counties of Gatineau, Hull, Labelle, Papineau, Pontiac and Tamiscamingue in the Province of Quebec). Lists of attorneys for other parts of Canada may be obtained from the U.S. Consulates General located in Calgary, Halifax, Montreal, Quebec City, Toronto and Vancouver. The Embassy’s mailing address is P.O. Box 866, Station “B”, Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5T1, tel: (613) 238- 5335. The Consular Section is located in the Embassy. Mail from the United States to Canada may be sent at the regular U.S. first class rate of 85 cents. Registered mail may be sent through the Canadian postal service and return receipts obtained. International reply coupons may be used to prepay postage on replies. The local address of the Canadian Bar Association is 865 Carling Avenue, Suite 500, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5S8 Tel: (613) 237-2925 or (613) 237-1988 or toll-free 1-800-267-8860. The Law Society of Upper Canada governs all lawyers from Ontario and every lawyer must be a member of the society in order to practice in the Province of Ontario. The address of the Law Society of Upper Canada is 130 Queen St., W., Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N6, Tel: 1-800-668-7380 or Direct Tel: (416) 947-3300. -

ITZ Loblaw Native Plant Store List 2021

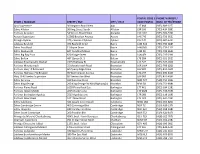

POSTAL CODE / PHONE NUMBER / STORE / MAGASIN STREET / RUE CITY / VILLE CODE POSTAL NUM. DE TÉLÉPHONE Ajax Superstore 30 Kingston Road West Ajax L1T 4K8 (905) 683-2272 Zehrs Alliston 30 King Street South Alliston L9R 1H6 (705) 434-9391 Fortinos Ancaster 54 Wilson Street West Ancaster L9G 1N2 (905) 304-5740 Aurora Superstore 15900 Bayview Avenue Aurora L4G 7Y3 (905) 726-9532 Provigo Aylmer 375, chemin d'Aylmer Aylmer J9H 1A5 (819) 682-4433 Loblaws Bayfield 472 Bayfield Street Barrie L4M 5A2 (705) 735-6689 Zehrs Essa Road 11 Bryne Drive Barrie L4N 8V8 (705) 733-1119 Zehrs Duckworth 607 Cundles Rd East Barrie L4M 0J7 (705) 722-3636 Zehrs Big Bay Point 620 Yonge Street Barrie L4N 4E6 (705) 735-2390 Zehrs Bolton 487 Queen St. S Bolton L7E 2B4 (905) 951-9555 Loblaws Bowmanville Market 2375 Highway #2 Bowmanville L1C 5A3 (905) 623-2600 Fortinos Mountainash 55 Mountainash Road Brampton L6R 1W4 (905) 793-8200 Fortinos Hwy 10 & Bovaird 60 Quarry Edge Drive Brampton L6V 4K2 (905) 453-3600 Fortinos Highway 7 & Brisdale 35 Worthington Avenue Brampton L7A 2Y7 (905) 495-8108 Hwy 10 & Steeles Superstore 85 Steeles Ave West Brampton L6Y 0B5 (905) 451-4999 Zehrs Fairview 410 Fairview Drive Brantford N3R 7V7 (519) 754-4932 Zehrs King George 290 King George Rd Nth/Highway24 Brantford N3R 5L8 (519) 751-8988 Fortinos Plains Road 1059 Plains Road East Burlington L7T 4K1 (905) 634-1591 Fortinos Upper Middle 2025 Guelph Line Burlington L7P 4M8 (905) 336-6566 Fortinos Burlington Appleby 2515 Appleby Line Burlington L7R 0B6 (905) 319-1690 Fortinos New Street 5111 New Street Burlington L7L 1V2 (905) 631-7227 Zehrs Caledonia 322 Argyle Street South Caledonia N3W 1K8 (905) 765-8207 Zehrs Cambridge Centre 400 Conestoga Blvd Cambridge N1R 7L7 (519) 620-1376 Zehrs Hespeler 180 Holiday Inn Drive Cambridge N3C 3Z4 (519) 658-4689 Zehrs South Cambridge 200 Franklin Blvd Cambridge N1R 5S2 (519) 624-8170 Provigo Le Marché Charlesbourg 4545, boul. -

Press Release for Immediate Release

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Jean-Marc Léveillé proposes a plan regarding housing Longueuil, June 29, 2021 — The mayoral candidate of Longueuil Citizen, Jean-Marc Léveillé, is concerned about the housing situation in Longueuil. Already last year, the pandemic complicated the move and the search for new housing, the situation this year shows no sign of improvement, while according to some estimates, around fifty families in Longueuil could find themselves homeless July 1st. While highlighting the efforts made this year by organizations and the City to support the citizens of Longueuil during this difficult period, the mayoral candidate of Longueuil Citoyen - Équipe Jean-Marc Léveillé proposes measures to increase the number of social and affordable housing units in Longueuil. To act now in order to accelerate the start of housing projects In the event of his election as Mayor of Longueuil, he intends to set up a municipal fund dedicated to accelerating the start of construction projects for social and affordable housing. Amounts that could have a leverage effect on several housing projects. An idea initially proposed in 2020 by Councillor Michel Lanctôt of the Antoinette-Robidoux District, which Jean-Marc Léveillé takes up in the commitments of Longueuil Citoyen. He also proposes that the City identify municipal buildings that could quickly be converted, as well as land that could accommodate new social or affordable rental housing projects. For the mayoral candidate of Longueuil Citoyen, the adoption of teleworking by our civil servants represents a unique opportunity for the City to consider the use of its real estate and land differently. -

Canada's Changing Language Realities and the Challenge Of

Canada’s Changing Language Realities and the Challenge of Bilingualism Part 1 Montreal increasingly trilingual (Gatineau most officially bilingual region in Quebec and city in Canada) Jack Jedwab January 9, 2007 Highlights -While elsewhere in Canada the objective of substantially increasing bilingualism seems improbable, in the Montreal region three languages are being more common for an important share of the region’s youth notably its growing allophone population acquiring both English and French. The 2006 census revealed that the level of official bilingualism amongst persons whose mother tongue is neither English nor French represented 50.2% of the Montreal population and thus it is fair to assume the majority of the city’s allophones are trilingual. Given the substantial growth of this group in Montreal the rate of trilingualism has increased from 16.5% in 2001 to 18% in 2006 with some 660 000 Montrealers knowing three languages. In fact some 94 000 Montrealers report knowledge of four languages representing nearly 3% of the metropolitan region’s population. In Canada some 2 million persons report knowledge of three languages representing some 6.4% of the population compared to 5.9% in 2001. -In 2006 Montrealers between the ages of 20 and 39 some one in four report knowledge of three languages. -Montreal is the most bilingual metropolitan area in the country, it is Gatineau that is Quebec’s most bilingual region and city in Canada. As Gatineau is part of the Ottawa-Gatineau metropolitan region its level of bilingualism as a city does not get the same notoriety as Montreal which is a CMA (in part three we will explore the evolution of bilingualism by age cohort in Gatineau compared to Ottawa, Ontario). -

Industry of Employment by Immigration Status a Comparison of Major Cities in Ontario and Quebec Key Findings

INDUSTRY OF EMPLOYMENT BY IMMIGRATION STATUS A COMPARISON OF MAJOR CITIES IN ONTARIO AND QUEBEC APRIL APRIL By Marshia Akbar, Brian Ray, Damaris Rose & Valerie Preston April 2019 a Marshia Akbar is a post-doctoral research fellow in the Department of Geography at York University. b Brian Ray is a professor in the Department of Geography, Environment and Geomatics at the University of Ottawa. c Damaris Rose is a professor of Urban Studies at in Montreal d Valerie Preston is a professor in the Department of Geography at York University and the principal investigator for the BMRC-IRMU Partnership. BMRC-IRMU REPORT II- April 2019 Industry of Employment by Immigration Status A Comparison of Major Cities in Ontario and Quebec Key Findings • In 2016, 83.2% of workers in Ontario and 81.8% of those in Quebec were employed in services. Between 2006 and 2016, health care and social assistance accounted for the largest increases in service sector employment in both provinces. • The share of workers employed in manufacturing declined in both provinces. It declined from 14.7% in 2006 to 10.4% in 2016 in Ontario and from 15.5% to 11.6% in Quebec. Despite the decline, manufacturing was still the third largest industrial sector by employment in both provinces in 2016. • The declining manufacturing and growing health care and social assistance sectors are the top two sectors of employment for foreign-born workers in Ontario and Quebec. Among Canadian-born workers, retail trade and health care and social assistance services are the top two sectors of employment. -

National Capital Commission

NATIONAL CAPITAL COMMISSION Summary of the Corporate Plan 2016–2017 to 2020–2021 www.ncc-ccn.gc.ca 202–40 Elgin Street, Ottawa, Canada K1P 1C7 Email: [email protected] • Fax: 613-239-5063 Telephone: 613-239-5000 • Toll-free: 1-800-465-1867 TTY: 613-239-5090 • Toll-free TTY: 1-866-661-3530 Unless otherwise noted, all imagery is the property of the National Capital Commission. National Capital Commission Summary of the Corporate Plan 2016–2017 to 2020–2021 Catalogue number: W91-2E-PDF ISSN: 1926-0490 The National Capital Commission is dedicated to building a dynamic, sustainable, inspiring capital that is a source of pride for all Canadians and a legacy for generations to come. NATIONAL CAPITAL COMMISSION ASSETS 10% The National Capital Commission owns over 10 percent of the lands in Canada’s Capital Region, totalling 473 km2, and 20 percent of the lands in the Capital’s core. This makes the National Capital Commission the region’s largest landowner. 361 km2 200 km2 The National Capital Commission is responsible The National Capital Commission is responsible for the management of Gatineau Park, which for the management of the Greenbelt, covers an area of 361 km2. Some 2.7 million which covers an area of 200 km2. The visits are made to Gatineau Park each year. Greenbelt provides 150 kilometres of trails for recreational activities. 106 km 15 The National Capital Commission owns The National Capital Commission manages 106 km of parkways in Ottawa and 15 urban parks and green spaces in the Gatineau Park, as well as over 200 km Capital Region, including Confederation Park, of recreational pathways that are part Vincent Massey Park, Major’s Hill Park and of the Capital Pathway network. -

COMMUNITY CONSERVATION PLAN for the Lac Deschênes – Ottawa River Important Bird Area

COMMUNITY CONSERVATION PLAN For the Lac Deschênes – Ottawa River Important Bird Area January, 2014 For the Lac Deschênes – Ottawa River Steering Committee Nature Canada Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Suggested citation .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 The IBA program ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Lac Deschênes - Ottawa River IBA ................................................................................................................... 6 Goals of this initiative ............................................................................................................................................... 7 2. IBA Site Information ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Figure 1: Proposed IBA -

Tourisme Outaouais

OFFICIAL TOURIST GUIDE 2018-2019 Outaouais LES CHEMINS D’EAU THE OUTAOUAIS’ TOURIST ROUTE Follow the canoeist on the blue signs! You will learn the history of the Great River and the founding people who adopted it. Reach the heart of the Outaouais with its Chemins d’eau. Mansfield-et-Pontefract > Mont-Tremblant La Pêche (Wakefield) Montebello Montréal > Gatineau Ottawa > cheminsdeau.ca contents 24 6 Travel Tools regional overview 155 Map 8 Can't-miss Experiences 18 Profile of the Region 58 top things to do 42 Regional Events 48 Culture & Heritage 64 Nature & Outdoor Activities 88 Winter Fun 96 Hunting & Fishing 101 Additional Activities 97 112 Regional Flavours accommodation and places to eat 121 Places to Eat 131 Accommodation 139 useful informations 146 General Information 148 Travelling in Quebec 150 Index 153 Legend of Symbols regional overview 155 Map TRAVEL TOOLS 8 Can't-miss Experiences 18 Profile of the Region Bring the Outaouais with you! 20 Gatineau 21 Ottawa 22 Petite-Nation La Lièvre 26 Vallée-de-la-Gatineau 30 Pontiac 34 Collines-de-l’Outaouais Visit our website suggestions for tours organized by theme and activity, and also discover our blog and other social media. 11 Website: outaouaistourism.com This guide and the enclosed pamphlets can also be downloaded in PDF from our website. Hard copies of the various brochures are also available in accredited tourism Welcome Centres in the Outaouais region (see p. 146). 14 16 Share your memories Get live updates @outaouaistourism from Outaouais! using our hashtag #OutaouaisFun @outaouais