Tonal Types and Modal Categories in Renaissance Polyphony Harold S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Concerning the Ontological Status of the Notated Musical Work in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

Concerning the Ontological Status of the Notated Musical Work in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries Leeman L. Perkins In her detailed and imaginative study of the concept of the musical work, The Imag;inary Museum of Musical Works (1992), Lydia Goehr has made the claim that, prompted by "changes in aesthetic theory, society, and poli tics," eighteenth century musicians began "to think about music in new terms and to produce music in new ways," to conceive of their art, there fore, not just as music per se, but in terms of works. Although she allows that her view "might be judged controversial" (115), she asserts that only at the end of the 1700s did the concept of a work begin "to serve musical practice in its regulative capacity," and that musicians did "not think about music in terms of works" before 1800 (v). In making her argument, she pauses briefly to consider the Latin term for work, opus, as used by the theorist and pedagogue, Nicolaus Listenius, in his Musica of 1537. She acknowledges, in doing so, that scholars in the field of music-especially those working in the German tradition-have long regarded Listenius's opening chapter as an indication that, by the sixteenth century, musical compositions were regarded as works in much the same way as paintings, statuary, or literature. She cites, for example, the monographs devoted to the question of "musical works of art" by Walter Wiora (1983) and Wilhelm Seidel (1987). She concludes, however, that their arguments do not stand up to critical scrutiny. There can be little doubt, surely, that the work-concept was the focus of a good deal of philosophical dispute and aesthetic inquiry in the course of the nineteenth century. -

Repertories. Tinctoris, Gaffurio and the Neapolitan Context*

GIANLUCA D'AGOSTINO READING THEORISTS FOR RECOVERING 'GHOST' REPERTORIES. TINCTORIS, GAFFURIO AND THE NEAPOLITAN CONTEXT* In 1478 the Italian theorist Franchino Gaffurio moved to Naples. The two-year stay at the local Aragonese court was essential for his edu cation for he had the opportunity to meet Johannes Tinctoris, who by that time had completed many of his known treatises. It has long been recognized that Tinctoris deeply influenced Gaffurio's thoughts on sever al controversial topics, such as proportions and mensuration signs, and the mensura! treatment of counterpoint.' Echoes, and even literal quotations, of Tinctoris' statements and crit icisms resound in Gaffurio's famous Practica musicae in four books (Mi lan, 1496), and- even more strongly- in his two earlier versions of sin gle books of the Practica (book 2: Musices practicabilis libellus; book 4: Tractatus practicabilium proportionum), compiled as independent treatis es soon after his departure from Naples, in the early 1480s. Many years * This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper read at the Med-Ren Music Conference held in Glagow, July 2004. It is ideally linked to two previous articles on similar topics already appeared in these «Studi Musicali» (:XXVIII-1999; X:XX-2001). Wormest thanks are due to Bonnie J. Blackbum, Margaret Bent and David Fallows, for their many help ful suggestions and improvements. 1 On this subject see: F. ALBERTO GALLO, Le traduzioni dal Greco per Franchino Gaffu rio, «Acta Musicologica», XXXV, 1963, pp. 172-174; ID., Citazioni da un trattato di Du/ay, «Collectanea Historiae Musicae», N, 1966, pp. 149-152; ID., lntrod. -

Johannes Tinctoris, in His Liber De Arte Contrapuncti

Ockeghem, Binchois, and Du Fay Johannes Tinctoris, in his Liber de arte contrapuncti of 1477, remarked on recent developments in the art of music and placed Johannes Ockeghem at the head of an exalted list of composers whose works exuded divine sweetness: Although it seems beyond belief, there does not exist a single piece of music, not composed within the last forty years, that is regarded by the learned as worth hearing. Yet at this present time, not to mention innumerable singers of the most beautiful diction, there flourish, whether by the effect of some celestial influence or by the force of assiduous practice, countless composers, among them Johannes Ockeghem, Johannes Regis, Antoine Busnoys, Firminus Caron, and Guillaume Faugues, who glory in having studied this divine art under John Dunstable, Gilles Binchois, and Guillaume Du Fay, recently deceased. Nearly all the works of these men exhale such sweetness that in my opinion they are to be considered most suitable, not only for men and heroes, but even for the immortal gods, Indeed, I never hear them, I never study them, without coming away more refreshed and wiser. Born in St-Ghislain in the county of Hainaut (now in Belgium) around 1420, Ockeghem enters the historical record in 1443 as a vicaire-chanteur at the church of Our Lady in Antwerp, a modest appointment appropriate to a young professional singer. By 1446 he had become one of seven singers in the chapel of Charles I, Duke of Bourbon, and in 1451 he joined the musical establishment of Charles VII, king of France. -

Program Notes FY20C1

Piffaro’s Beginning Ah, Beginnings…they can be exciting, stimulating and even a little scary at times. They may mark a break with the preexistent in an attempt to chart some new course, or revive an older, lost tradition. So it was with a fledgling group of reed players from the Collegium Musicum at the University of Pennsylvania in 1980, when they decided to launch their own ensemble, calling it simply and graphically, the Renaissance Wind Band. Their intent was to pursue renaissance wind playing, especially the double-reed instruments, the shawms, dulcians, krumhorns and bagpipes, in a way that was lacking in the nascent early music revival in this country at the time, at least on a professional level. It was a courageous and daring leap into the unknown in many ways. And it was Piffaro’s beginning! On a somewhat ragtag collection of instruments, the best available at the time, the group formed a 5-part band and began collecting repertoire, teaching themselves the challenging techniques demanded by the horns, learned how to make successful reeds and figured out who played what, when and how. It was exciting and groundbreaking, something new and uncharted. As with many a nascent experiment in group formation, personnel changed over the first 4 years of ensemble building, but eventually settled into a coterie of like- minded individuals committed to creating an entity with roots that might support the growth of a vibrant and lasting ensemble. What’s a musical ensemble to do but perform, so by the winter of 1984 the group decided it was time to go public, to make the leap into that great unknown of audience response. -

MUSIC in the RENAISSANCE Western Music in Context: a Norton History Walter Frisch Series Editor

MUSIC IN THE RENAISSANCE Western Music in Context: A Norton History Walter Frisch series editor Music in the Medieval West, by Margot Fassler Music in the Renaissance, by Richard Freedman Music in the Baroque, by Wendy Heller Music in the Eighteenth Century, by John Rice Music in the Nineteenth Century, by Walter Frisch Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries, by Joseph Auner MUSIC IN THE RENAISSANCE Richard Freedman Haverford College n W. W. NORTON AND COMPANY Ƌ ƋĐƋ W. W. Norton & Company has been independent since its founding in 1923, when William Warder Norton and Mary D. Herter Norton first published lectures delivered at the People’s Institute, the adult education division of New York City’s Cooper Union. The firm soon expanded its program beyond the Institute, publishing books by celebrated academics from America and abroad. By midcentury, the two major pillars of Norton’s publishing program—trade books and college texts— were firmly established. In the 1950s, the Norton family transferred control of the company to its employees, and today—with a staff of four hundred and a comparable number of trade, college, and professional titles published each year—W. W. Norton & Company stands as the largest and oldest publishing house owned wholly by its employees. Copyright © 2013 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Editor: Maribeth Payne Associate Editor: Justin Hoffman Assistant Editor: Ariella Foss Developmental Editor: Harry Haskell Manuscript Editor: Bonnie Blackburn Project Editor: Jack Borrebach Electronic Media Editor: Steve Hoge Marketing Manager, Music: Amy Parkin Production Manager: Ashley Horna Photo Editor: Stephanie Romeo Permissions Manager: Megan Jackson Text Design: Jillian Burr Composition: CM Preparé Manufacturing: Quad/Graphics-Fairfield, PA A catalogue record is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-393-92916-4 W. -

The Sources and the Performing Traditions. Alexander Agricola: Musik Zwischen Vokalität Und Instrumentalismus, Ed

Edwards, W. (2006) Agricola's songs without words: the sources and the performing traditions. Alexander Agricola: Musik zwischen Vokalität und Instrumentalismus, ed. Nicole Schwindt, Trossinger Jahrbuch für Renaissancemusik 6:pp. 83-121. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/4576/ 21th October 2008 Glasgow ePrints Service https://eprints.gla.ac.uk Warwick Edwards Agricola’s Songs Without Words The Sources and the Performing Traditions* In 1538 the Nuremberg printer Hieronymus Formschneider issued a set of part- books entitled Trium vocum carmina1 and containing a retrospective collection of one hundred untexted and unattributed three-voice compositions, six of which can be assigned to Agricola. Whoever selected them and commissioned the publication added a preface (transcribed, with English translation in Appendix pp. 33–4) that offers – most unusually for the time – a specific explanation for leaving out all the words. This turns out to have nothing to do with performance, let alone the possible use of instruments, which are neither ruled in nor ruled out. Nor does it express any worries about readers’ appetites for texts in foreign languages, or mention that some texts probably never existed in the first place. Instead, the author pleads, rather surprisingly, that the appearance of the books would have been spoilt had words variously in German, French, Italian and Latin been mixed in together. Moreover, the preface continues, the composers of the songs had regard for erudite sonorities rather than words. The learned musician, then, will enjoy the -

Lagrime Di San Pietro

Lagrime di San Pietro Orlando di Lasso / Composer Los Angeles Master Chorale Grant Gershon / Artistic Director Grant Gershon / Conductor Peter Sellars / Director James F. Ingalls / Lighting Designer Danielle Domingue / Costume Designer Pamela Salling / Stage Manager Sunday Evening, January 20, 2019 at 7:00 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor 25th Performance of the 140th Annual Season 140th Annual Choral Union Series Choral Music Series This evening’s performance is supported by Carl and Charlene Herstein. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM. Special thanks to Matthew Ozawa for his participation in events surrounding this evening’s performance. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of lobby floral art for this evening’s performance. Lagrime di San Pietro appears by arrangement with David Lieberman Artists’ Representatives. In consideration for the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. PROGRAM Orlando di Lasso Lagrime di San Pietro (Tears of St. Peter) I. Il Magnanimo Pietro (When the generous Peter) II. Ma gli archi (The bows, however) III. Tre volte haveva (Three times already) IV. Qual a l’incontro (No one should boast) V. Giovane donna (Never did a young lady) VI. Cosi talhor (As it happens) VII. Ogni occhio del Signor (The eyes of the Lord) VIII. Nessun fedel trovai (I found none faithful) IX. Chi ad una ad una (If one could retell one by one) X. Come falda di neve (Like a snowbank) XI. E non fu il pianot suo (And his crying) XII. -

Persona, Print, and Propaganda: Orlando Di Lasso and Constructions of Self in Counter-Reformation Bavaria

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2019 PERSONA, PRINT, AND PROPAGANDA: ORLANDO DI LASSO AND CONSTRUCTIONS OF SELF IN COUNTER-REFORMATION BAVARIA Tara Leigh Jordan University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Recommended Citation Jordan, Tara Leigh, "PERSONA, PRINT, AND PROPAGANDA: ORLANDO DI LASSO AND CONSTRUCTIONS OF SELF IN COUNTER-REFORMATION BAVARIA. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/5458 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Tara Leigh Jordan entitled "PERSONA, PRINT, AND PROPAGANDA: ORLANDO DI LASSO AND CONSTRUCTIONS OF SELF IN COUNTER- REFORMATION BAVARIA." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Rachel May Golden, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Nathan Fleshner, Jacqueline Avila Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) PERSONA, PRINT, AND PROPAGANDA: ORLANDO DI LASSO AND CONSTRUCTIONS OF SELF IN COUNTER-REFORMATION BAVARIA A Thesis Presented for the Master of Music Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Tara Leigh Jordan May 2019 Copyright © 2019 by Tara Leigh Jordan. -

The Trombone in A: Repertoire and Performance

THE TROMBONE IN A: REPERTOIRE AND PERFORMANCE TECHNIQUES IN VENICE IN THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURY by BODIE JOHN PFOST A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2015 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Bodie John Pfost Title: The Trombone in A: Repertoire and Performance Techniques in Venice in the Early Seventeenth Century This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Marc Vanscheeuwijck Chairperson Margret Gries Member Henry Henniger Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2015 ii © 2015 Bodie John Pfost CC-BY-NC-SA iii THESIS ABSTRACT Bodie John Pfost Master of Arts School of Music and Dance December 2015 Title: The Trombone in A: Repertoire and Performance Techniques in Venice in the Early Seventeenth Century Music published in Venice, Italy in the first half of the seventeenth century includes a substantial amount specifying the trombone. The stylistic elements of this repertoire require decisions regarding general pitch, temperament, and performing forces. Within the realm of performing forces lie questions about specific instrument pitch and compositional key centers. Limiting this study to repertoire performed and published in approximately the first half of the seventeenth century allows a focus on specific performance practice decisions that underline the expressive elements of the repertoire. -

La Solennisation Du Plain-Chant À L'abbaye De Saint-Gall Au Xvie

T HÉORIE ET PRATIQUE DE LA MUSIQUE ANCIENNE – J OURNÉES D ’ ÉTUDES Jérémie Couleau La solennisation du plain-chant à l’abbaye de Saint-Gall au XVIe siècle L’histoire de la Suisse nous est très tôt parvenue en France sous la plume de François Robert, géographe ordinaire du Roi. Ce membre de l’académie de Berlin fait publier en 1789 un ouvrage intitulé Voyage dans les XIII cantons suisses, les grisons, le vallais, et autres pays et états alliés, ou sujets des suisses 1. Hormis certaines descriptions inhérentes au genre du carnet de voyage, le premier tome est l’occasion pour l’auteur d’évoquer, au grès des étapes, quelques épisodes historiques marquants. Après avoir quitté les eaux claires du lac de Constance, François Robert nous conduit dans les pâturages menant à l’abbaye bénédictine de Saint-Gall, dont il loue l’architecture, l’ornementation de l’église et la bibliothèque, avant d’évoquer le passé tourmenté de l’institution. Au mois de Février 1529, les habitans de Saint-Gall, qui avoient embrassé la Réformation, pensèrent à détruire les confessionaux dans l’église abbatiale, les autels, & les images. La chose fut résolue par les Magistrats assemblés en Conseil Souverain. L’ordre donné, en moins de deux heures toutes les figures & statues furent mises en monceau. […] Les Religieux, obligés de plier devant la force, se retirèrent à Notre-Dame des Hermites, au Canton de Switz : les Réformés firent l’office dans l’abbaye, mais les choses furent rétablies dans le premier état 2. L’épisode relaté par François Robert permet de penser que la guerre entre protestants et catholiques eut une résonance particulière au sein de l’abbaye de Saint-Gall. -

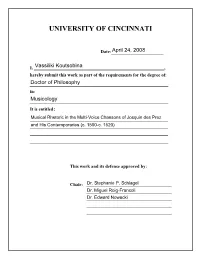

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Musical Rhetoric in the Multi-Voice Chansons of Josquin des Prez and His Contemporaries (c. 1500-c. 1520) A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Division of Composition, Musicology and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music By VASSILIKI KOUTSOBINA B.S., Chemistry University of Athens, Greece, April 1989 M.M., Music History and Literature The Hartt School, University of Hartford, Connecticut, May 1994 Committee Chair: Dr. Stephanie P. Schlagel 2008 ABSTRACT The first quarter of the sixteenth century witnessed tightening connections between rhetoric, poetry, and music. In theoretical writings, composers of this period are evaluated according to their ability to reflect successfully the emotions and meaning of the text set in musical terms. The same period also witnessed the rise of the five- and six-voice chanson, whose most important exponents are Josquin des Prez, Pierre de La Rue, and Jean Mouton. The new expanded textures posed several compositional challenges but also offered greater opportunities for text expression. Rhetorical analysis is particularly suitable for this repertory as it is justified by the composers’ contacts with humanistic ideals and the newer text-expressive approach. Especially Josquin’s exposure to humanism must have been extensive during his long-lasting residence in Italy, before returning to Northern France, where he most likely composed his multi- voice chansons.