Contrasting the Social Cognition of Humans and Nonhuman Apes: the Shared Intentionality Hypothesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Livability Court Records 1/1/1997 to 8/31/2021

Livability Court Records 1/1/1997 to 8/31/2021 Last First Middle Case Charge Disposition Disposition Date Judge 133 Cannon St Llc Rep JohnCompany Q Florence U43958 Minimum Standards For Vacant StructuresGuilty 8/13/18 Molony 148 St Phillips St Assoc.Company U32949 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 10/17/11 Molony 18 Felix Llc Rep David BevonCompany U34794 Building Permits; Plat and Plans RequiredGuilty 8/13/18 Mendelsohn 258 Coming Street InvestmentCompany Llc Rep Donald Mitchum U42944 Public Nuisances Prohibited Guilty 12/18/17 Molony 276 King Street Llc C/O CompanyDiversified Corporate Services Int'l U45118 STR Failure to List Permit Number Guilty 2/25/19 Molony 60 And 60 1/2 Cannon St,Company Llc U33971 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 8/29/11 Molony 60 Bull St Llc U31469 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 8/29/11 Molony 70 Ashe St. Llc C/O StefanieCompany Lynn Huffer U45433 STR Failure to List Permit Number N/A 5/6/19 Molony 70 Ashe Street Llc C/O CompanyCobb Dill And Hammett U45425 STR Failure to List Permit Number N/A 5/6/19 Molony 78 Smith St. Llc C/O HarrisonCompany Malpass U45427 STR Failure to List Permit Number Guilty 3/25/19 Molony A Lkyon Art And Antiques U18167 Fail To Follow Putout Practices Guilty 1/22/04 Molony Aaron's Deli Rep Chad WalkesCompany U31773 False Alarms Guilty 9/14/16 Molony Abbott Harriet Caroline U79107 Loud & Unnecessary Noise Guilty 8/23/10 Molony Abdo David W U32943 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 8/29/11 Molony Abdo David W U37109 Public Nuisances Prohibited Guilty 2/11/14 Pending Abkairian Sabina U41995 1st Offense - Failing to wear face coveringGuilty or mask. -

Chimpanzee Rights: the Philosophers' Brief

Chimpanzee Rights: The Philosophers’ Brief By Kristin Andrews Gary Comstock G.K.D. Crozier Sue Donaldson Andrew Fenton Tyler M. John L. Syd M Johnson Robert C. Jones Will Kymlicka Letitia Meynell Nathan Nobis David M. Peña-Guzmán Jeff Sebo 1 For Kiko and Tommy 2 Contents Acknowledgments…4 Preface Chapter 1 Introduction: Chimpanzees, Rights, and Conceptions of Personhood….5 Chapter 2 The Species Membership Conception………17 Chapter 3 The Social Contract Conception……….48 Chapter 4 The Community Membership Conception……….69 Chapter 5 The Capacities Conception……….85 Chapter 6 Conclusions……….115 Index 3 Acknowledgements The authors thank the many people who have helped us throughout the development of this book. James Rocha, Bernard Rollin, Adam Shriver, and Rebecca Walker were fellow travelers with us on the amicus brief, but were unable to follow us to the book. Research assistants Andrew Lopez and Caroline Vardigans provided invaluable support and assistance at crucial moments. We have also benefited from discussion with audiences at the Stanford Law School and Dalhousie Philosophy Department Colloquium, where the amicus brief was presented, and from the advice of wise colleagues, including Charlotte Blattner, Matthew Herder, Syl Ko, Tim Krahn, and Gordon McOuat. Lauren Choplin, Kevin Schneider, and Steven Wise patiently helped us navigate the legal landscape as we worked on the brief, related media articles, and the book, and they continue to fight for freedom for Kiko and Tommy, and many other nonhuman animals. 4 1 Introduction: Chimpanzees, Rights, and Conceptions of Personhood In December 2013, the Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) filed a petition for a common law writ of habeas corpus in the New York State Supreme Court on behalf of Tommy, a chimpanzee living alone in a cage in a shed in rural New York (Barlow, 2017). -

Virunga 2015-2016 Surveys

Virunga 2015-2016 Surveys Monitoring Mountain Gorillas, Other Select Mammals, and Illegal Activities Virunga 2015-2016 Surveys Monitoring Mountain Gorillas, Other Select Mammals, and Illegal Activities FINAL REPORT April 2019 Jena R. Hickey, Anne-Céline Granjon, Linda Vigilant, Winnie Eckardt, Kirsten Gilardi, Mike Cranfield, Abel Musana, Anna Behm Masozera, Dennis Babaasa, Fidele Ruzigandekwe, & Martha M. Robbins Citation1: Hickey, J.R., Granjon, A.C., Vigilant, L., Eckardt, W., Gilardi, K.V., Cranfield, M., Musana, A., Masozera, A.B., Babaasa, D., Ruzigandekwe, F., & Robbins, M.M. 2019. Virunga 2015–2016 surveys: monitoring mountain gorillas, other select mammals, and illegal activities. GVTC, IGCP & partners, Kigali, Rwanda. 1 Cited in Hickey et al. (2018) as: Hickey, J.R., Granjon, A.C., Vigilant, L., Eckardt, W., Gilardi, K.V., Babaasa, D., Ruzigandekwe, F., Leendertz, F.H. & Robbins, M.M. 2018. Virunga 2015–2016 surveys: monitoring mountain gorillas, other select mammals, and illegal activities. GVTC, IGCP & partners, Kigali, Rwanda. 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Résumé ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Methods ............................................................................................................................................... -

EMNLP-IJCNLP 2019 Poster & Demo Guide Tuesday, November 5

EMNLP-IJCNLP 2019 Poster & Demo Guide Tuesday, November 5 Poster & Demo Session 1: Information Extraction, Information Retrieval and Document Analysis, Linguistic Theories Poster/ Session Demo # Title Authors Note Leveraging Dependency Forest for Neural Medical Relation Linfeng Song, Yue Zhang, Daniel Gildea, Mo Yu, Zhiguo Wang and 1E P1 Extraction jinsong su Open Relation Extraction: Relational Knowledge Transfer Ruidong Wu, Yuan Yao, Xu Han, Ruobing Xie, Zhiyuan Liu, Fen Lin, 1E P2 from Supervised Data to Unsupervised Data Leyu Lin and Maosong Sun 1E P3 Improving Relation Extraction with Knowledge-attention Pengfei Li, Kezhi Mao, Xuefeng Yang and Qi Li Jointly Learning Entity and Relation Representations for Yuting Wu, Xiao Liu, Yansong Feng, Zheng Wang and Dongyan 1E P4 Entity Alignment Zhao Tackling Long-Tailed Relations and Uncommon Entities in 1E P5 Knowledge Graph Completion Zihao Wang, Kwunping Lai, Piji Li, Lidong Bing and Wai Lam Low-Resource Name Tagging Learned with Weakly Labeled 1E P6 Data Yixin Cao, Zikun Hu, Tat-seng Chua, Zhiyuan Liu and Heng Ji Learning Dynamic Context Augmentation for Global Entity Xiyuan Yang, Xiaotao Gu, Sheng Lin, Siliang Tang, Yueting Zhuang, 1E P7 Linking Fei Wu, Zhigang Chen, Guoping Hu and Xiang Ren Open Event Extraction from Online Text using a Generative 1E P8 Adversarial Network Rui Wang, Deyu ZHOU and Yulan He 1E P9 Learning to Bootstrap for Entity Set Expansion Lingyong Yan, Xianpei Han, Le Sun and Ben He Multi-Input Multi-Output Sequence Labeling for Joint Tianwen Jiang, Tong Zhao, Bing -

Conference Program July 26-29, 2021 | Pacific Daylight Time 2021 Asee Virtual Conference President’S Welcome

CONFERENCE PROGRAM JULY 26-29, 2021 | PACIFIC DAYLIGHT TIME 2021 ASEE VIRTUAL CONFERENCE PRESIDENT’S WELCOME SMALL SCREEN, SAME BOLD IDEAS It is my honor, as ASEE President, to welcome you to the 128th ASEE Annual Conference. This will be our second and, almost certainly, final virtual conference. While we know there are limits to a virtual platform, by now we’ve learned to navigate online events to make the most of our experience. Last year’s ASEE Annual Conference was a success by almost any measure, and all of us—ASEE staff, leaders, volunteers, and you, our attendees—contributed to a great meeting. We are confident that this year’s event will be even better. Whether attending in person or on a computer, one thing remains the same, and that’s the tremendous amount of great content that ASEE’s Annual Conference unfailingly delivers. From our fantastic plenary speakers, paper presentations, and technical sessions to our inspiring lineup of Distinguished Lectures and panel discussions, you will have many learning opportunities and take-aways. I hope you enjoy this week’s events and please feel free to “find” me and reach out with any questions or comments! Sincerely, SHERYL SORBY ASEE President 2020-2021 2 Schedule subject to change. Please go to https://2021asee.pathable.co/ for up-to-date information. 2021 ASEE VIRTUAL CONFERENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 ASEE VIRTUAL CONFERENCE AND EXPOSITION PROGRAM ASEE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ................................................................................4 CONFERENCE-AT-A-GLANCE ................................................................................6 -

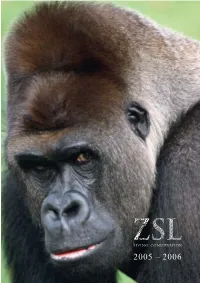

2005 – Building for the Future

2005 – 2006 2005 – Building for the future Working with communities is an important part of ZSL’s effort to involve local people in the welfare of their wildlife Reading this year’s Living Conservation report I am struck by the sheer breadth and vitality of ZSL’s conservation work around the world. It is also extremely gratifying to observe so many successes, ranging from our international animal conservation and scientific research programmes to our breeding of endangered animals and educational projects. Equally rewarding was our growing Zoology at the University of financial strength during 2005. In a year Cambridge. This successful overshadowed by the terrorist attacks collaboration with our Institute of in the capital, ZSL has been able to Zoology has generated numerous demonstrate solid and sustained programmes of research. We are financial growth, with revenue from our delighted that this partnership will website, retailing, catering and business continue for another five years. development operations all up on last Our research projects continued to year. influence policy in some of the world’s In this year’s report we have tried to leading conservation fields, including give greater insight into some of our the trade in bushmeat, the assessment most exciting conservation programmes of globally threatened species, disease – a difficult task given there are so risks to wildlife, and the ecology and many. Fortunately, you can learn more behaviour of our important native about our work on our award-winning* species. website www.zsl.org (*Best Website – At Regent’s Park we opened another Visit London Awards November 2005). two new-look enclosures. -

Laboratory Primate Newsletter

LABORATORY PRIMATE NEWSLETTER Vol. 42, No. 2 April 2003 JUDITH E. SCHRIER, EDITOR JAMES S. HARPER, GORDON J. HANKINSON AND LARRY HULSEBOS, ASSOCIATE EDITORS MORRIS L. POVAR, CONSULTING EDITOR ELVA MATHIESEN, ASSISTANT EDITOR ALLAN M. SCHRIER, FOUNDING EDITOR, 1962-1987 Published Quarterly by the Schrier Research Laboratory Psychology Department, Brown University Providence, Rhode Island ISSN 0023-6861 POLICY STATEMENT The Laboratory Primate Newsletter provides a central source of information about nonhuman primates and re- lated matters to scientists who use these animals in their research and those whose work supports such research. The Newsletter (1) provides information on care and breeding of nonhuman primates for laboratory research, (2) dis- seminates general information and news about the world of primate research (such as announcements of meetings, research projects, sources of information, nomenclature changes), (3) helps meet the special research needs of indi- vidual investigators by publishing requests for research material or for information related to specific research prob- lems, and (4) serves the cause of conservation of nonhuman primates by publishing information on that topic. As a rule, research articles or summaries accepted for the Newsletter have some practical implications or provide general information likely to be of interest to investigators in a variety of areas of primate research. However, special consid- eration will be given to articles containing data on primates not conveniently publishable elsewhere. General descrip- tions of current research projects on primates will also be welcome. The Newsletter appears quarterly and is intended primarily for persons doing research with nonhuman primates. Back issues may be purchased for $5.00 each. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

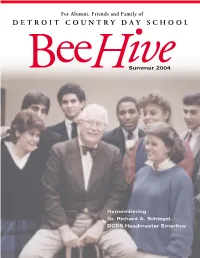

For Alumni, Friends and Family of DETROIT COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL

For Alumni, Friends and Family of DETROIT COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL Summer 2004 Remembering Dr. Richard A. Schlegel, DCDS Headmaster Emeritus THE BEEHIVE IS PUBLISHED TWICE ANNUALLY FOR ALUMNI, PARENTS, PAST PARENTS, STUDENTS AND FRIENDS OF DETROIT COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL HEADMASTER GERALD T. HANSEN EDITOR MARY ELLEN ROWE PHOTOGRAPHY SCOTT C. BERTSCHY CLAYTON T. MATTHEWS DEVELOPMENT OFFICE STAFF DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT SCOTT C. BERTSCHY ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT BARBARA A. MOWER AND PARENT RELATIONS DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS KIRA T. MANN ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS JEAN L. CROSSLEY DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS CLAYTON T. MATTHEWS ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS MARY ELLEN ROWE ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT KIMBERLY M. ARNOLD ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT DONNA CRONBERGER ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT JACKIE MARTIN BEEHIVE DESIGN AND PRODUCTION SUSAN BACHMAN ’76, MARKET ARTS Front cover: Dr. Schlegel surrounds himself with Country Day students in 1986. (L-R) Natalie Greenspan ‘86, Bill Passer ‘86, Keith Fenton ‘86, Dr. Schlegel, Dennis Archer ‘86, Kathy Williams ‘87, Carol Gillow Giles ‘86 and David Levine ‘86. Contents BeeHive • Summer 2004 A NOTE FROM THE HEADMASTER 2 16 BEEHIVE CORRECTIONS 3 CAMPUS BRIEFS 3 REMEMBERING DR. SCHLEGEL 6 CLASS OF 2004 COMMENCEMENT 10 2004 HONORS CONVOCATION 12 AS SEEN IN... THE TRAVERSE CITY 13 RECORD EAGLE DCDS NAMED MICROSOFT CENTER 14 23 OF INNOVATION 24 DCDS CELEBRATES THE ARTS 16 BEACH BASH! AUCTION 2004 18 FLAT STANLEY MANIA AT THE 19 LOWER SCHOOL JUNIOR SCHOOL MOOSE 20 REVEALS HIS ROOTS VISITING ARTIST JACK GANTOS WROTE 22 THE BOOK ON STORYTELLING GRADE 7 FLORIDA TRIP 23 A DAY TIMES SPECIAL - HANDS ON 24 DETROIT GIVES BACK TO THE CITY DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS 25 MESSAGE CAREER DAY 2004 26 6 2004 REGIONAL RECEPTIONS 28 THAT’S AMORÉ! FINE DINING WITH 29 ADRIAN TONON ‘91 ALUMNI SPORTS 32 ALUMNI MOTHERS’ LUNCHEON 34 RETIREMENTS 35 CLASS NOTES 37 IN MEMORIAM 45 32 CONTENTS 1 A Note from The Headmaster By Gerald T. -

Pan-Homo Culture and Theological Primatology

Page 1 of 9 Original Research Locating nature and culture:Pan-Homo culture and theological primatology Author: Studies of chimpanzee and bonobo social and learning behaviours, as well as diverse 1,2 Nancy R. Howell explorations of language abilities in primates, suggest that the attribution of ‘culture’ to Affiliations: primates other than humans is appropriate. The underestimation of primate cultural and 1Saint Paul School of cognitive characteristics leads to minimising the evolutionary relationship of humans and Theology, Overland Park, other primates. Consequently my claim in this reflection is about the importance of primate Kansas, United States studies for the enhancement of Christian thought, with the specific observation that the bifurcation of nature and culture may be an unsustainable feature of any world view, which 2Department of Dogmatics and Christian Ethics, includes extraordinary status for humans (at least, some humans) as a key presupposition. University of Pretoria, Intradisciplinary and/or interdisciplinary implications: The scientific literature concerning South Africa primate studies is typically ignored by Christian theology. Reaping the benefits of dialogue Correspondence to: between science and religion, Christian thought must engage and respond to the depth of Nancy Howell primate language, social, and cultural skills in order to better interpret the relationship of nature and culture. Email: [email protected] Postal address: Introduction 4370 West 109th Street, Suite 300, Overland Park, Concentration keeps me attentive to details, but also makes me selective about what is pushed Kansas 66211-1397, to margins. Sometimes I regret what I have missed. On a visit to the Iowa Primate Learning United States Sanctuary a few years ago, I was intensely focused on committee business at hand. -

The Chimpanzee Mind: in Search of the Evolutionary Roots of the Human Mind

Anim Cogn (2009) 12 (Suppl 1):S1–S9 DOI 10.1007/s10071-009-0277-1 REVIEW The chimpanzee mind: in search of the evolutionary roots of the human mind Tetsuro Matsuzawa Received: 25 September 2008 / Revised: 3 August 2009 / Accepted: 4 August 2009 / Published online: 29 August 2009 © Springer-Verlag 2009 Abstract The year 2008 marks the 60th anniversary of Keywords Chimpanzee · Psychophysics · Comparative Japanese primatology. Kinji Imanishi (1902–1992) Wrst vis- cognitive science · Field experiment · Participation ited Koshima island in 1948 to study wild Japanese mon- observation · Ai project keys, and to explore the evolutionary origins of human society. This year is also the 30th anniversary of the Ai pro- ject: the chimpanzee Ai Wrst touched the keyboard con- Sixty years of Japanese primatology and the Ai project nected to a computer system in 1978. This paper summarizes the historical background of the Ai project, The year 2008 is the 60th anniversary of the birth of Japanese whose principal aim is to understand the evolutionary ori- primatology. Kinji Imanishi (1902–1992) Wrst arrived on gins of the human mind. The present paper also aims to Koshima island to study Japanese monkeys in the wild on 3 present a theoretical framework for the discipline called December 1948 (Matsuzawa and McGrew 2008). Imanishi comparative cognitive science (CCS). CCS is characterized and his colleagues were interested in the evolutionary origins by the collective eVorts of researchers employing a variety of human society. They thus decided to study monkey socie- of methods, together taking a holistic approach to under- ties, exploring various aspects of ecology and behavior: domi- stand the minds of nonhuman animals. -

Letting the Apes Run the Zoo: Using Tort Law to Provide Animals with a Legal Voice

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 40 Issue 4 Article 6 4-20-2013 Letting the Apes Run the Zoo: Using Tort Law to Provide Animals with a Legal Voice Tania Rice Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the Animal Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Tania Rice Letting the Apes Run the Zoo: Using Tort Law to Provide Animals with a Legal Voice, 40 Pepp. L. Rev. Iss. 4 (2013) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol40/iss4/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 06 RICE SSRN.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 5/15/13 8:23 PM Letting the Apes Run the Zoo: Using Tort Law to Provide Animals with a Legal Voice I. INTRODUCTION II. IF ANIMALS COULD TALK (OR IF HUMANS COULD LISTEN) A. The Great Apes B. Cetaceans and Elephants C. Other Species D. New Standards in Scientific Use of Chimpanzees III. ESCAPING THROUGH THE ZOO BARS: CURRENT ANIMAL LAWS A. Animal Welfare Legislation 1. Federal Regulation of Animal Practices 2. State Animal Abuse Statutes 3. The Ineffectiveness of the Federal and State Legislation B. Seeking Judicial Protection IV. A NEW BREED OF IDEAS V. CAN WE SPARE THE ZOO KEY? A. The Rights Approach B. The Welfare Approach VI.