The Recorded Heritage of Willem Mengelberg and Its Aesthetic Relevance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

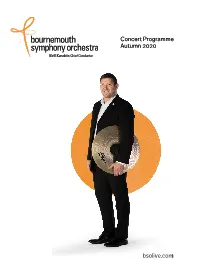

Bsolive.Com Concert Programme Autumn 2020 Bsolive.Com Concert

Concert Programme Autumn 2020 bsolive.com Welcome It’s my great pleasure to welcome you to this What amazing musical portraits Elgar week’s BSO concert of two British created in this dazzling sequence of masterworks, and a gem by Fauré. inventive musical vignettes, for instance, to name but three - the humorous Troyte, the The Britten and Elgar works hold special serious intellect of A.J Jaeger aka ‘Nimrod’, resonances for me. I’d been taken on holiday and the bulldog Dan, the beloved pet of to the Suffolk coast as a child, and when, George Sinclair, organist of Hereford aged fourteen, I first saw Peter Grimes, I was Cathedral, paddling furiously up the river totally bowled over by the power of the Wye. music, and the way it evoked, especially in the Four Sea Interludes, those East Anglican In between, I’m relishing the prospect of the landscapes and coast seascapes that I BSO’s Principal Cello, Jesper Svedberg, remembered. Later, at university in Norwich, bringing his poetic musicianship to Fauré’s I had the privilege of singing under Britten at haunting Élégie. I’m also looking forward to the Aldeburgh Festival, as well as meeting hearing the Britten and Elgar conducted by him at his home, The Red House. For me, David Hill, whose interpretations of English these memories are unforgettable. music are second to none, witnessed, not just in his performances, but also in his Elgar was another discovery of my teens; superb recordings, many, of course, with the when growing up in Birmingham, BSO. Worcestershire and Elgar country was only a couple of hours bus ride away. -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

All Strings Considered a Subjective List of Classical Works

All Strings Considered A Subjective List of Classical Works & Recordings All Recordings are available from the Lake Oswego Public Library These are my faves, your mileage may vary. Bill Baars, Director Composer / Title Performer(s) Comments Middle Ages and Renaissance Sequentia We carry a lot of plainsong and chant; HILDEGARD OF BINGEN recordings by the Anonymous 4 are also Antiphons highly recommended. Various, Renaissance vocal and King’s Consort, Folger Consort instrumental collections. or Baltimore Consort Baroque Era Biondi/Europa Galante or Vivaldi wrote several hundred concerti; try VIVALDI Loveday/Marriner. the concerti for multiple instruments, and The Four Seasons the Mandolin concerti. Also, Corelli's op. 6 and Tartini (my fave is his op.96). HANDEL Asch/Scholars Baroque For more Baroque vocal, Bach’s cantatas - Messiah Ensemble, Shaw/Atlanta start with 80 & 140, and his Bach B Minor Symphony Orch. or Mass with John Gardiner conducting. And for Jacobs/Freiberg Baroque fun, Bach's “Coffee” cantata. orch. HANDEL Lamon/Tafelmusik For an encore, Handel's “Music for the Royal Water Music Suites Fireworks.” J.S. BACH Akademie für Alte Musik Also, the Suites for Orchestra; the Violin and Brandenburg Concertos Berlin or Koopman, Pinnock, Harpsicord Concerti are delightful, too. or Tafelmusik J.S. BACH Walter Gerwig More lute - anything by Paul O'Dette, Ronn Works for Lute McFarlane & Jakob Lindberg. Also interesting, the Lute-Harpsichord. J.S. BACH Bylsma on period cellos, Cello Suites Fournier on a modern instrument; Casals' recording was the standard Classical Era DuPre/Barenboim/ECO & HAYDN Barbirolli/LSO Cello Concerti HAYDN Fischer, Davis or Kuijiken "London" Symphonies (93-101) HAYDN Mosaiques or Kodaly quartets Or start with opus 9, and take it from there. -

Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas--Artur Schnabel (1932-1935) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by James Irsay (Guest Post)*

The Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas--Artur Schnabel (1932-1935) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by James Irsay (guest post)* Artur Schnabel Austrian pianist Artur Schnabel has been called “the man who invented Beethoven”... a strange thing to say considering Schnabel was born more than half a century after Beethoven, universally recognized as the greatest composer in Europe, died in 1827. What, then, did Artur Schnabel invent? The 32 piano sonatas of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) represent one of the great artistic achievements in human history, and stand as the musical autobiography of the great composer's maturity, from his 25th until his 53rd year, four years before his death. The fruit of those years mark a staggering creative journey that began and ended in the composer's adopted home of Vienna, “Music Central” to the German-speaking world. Beethoven's musical path led from the domain of Haydn and Mozart to the world of his late period, when the agonizing progress of his deafness had become complete. By then, Beethoven's musical narrative had begun to speak a new language, proceeding according to a new logic that left many listeners behind. While the beauties of his music and his deep genius were generally recognized, at the same time, it was thought by some critics that Beethoven frequently smudged things up with his overly- bold, unfettered invention, even well before his final period: Beethoven, who is often bizarre and baroque, takes at times the majestic flight of an eagle, and then creeps in rocky pathways. He first fills the soul with sweet melancholy, and then shatters it by a mass of shattered chords. -

Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a Theme By

RACHMANINOFF’S RHAPSODY ON A THEME BY PAGANINI, OP. 43: ANALYSIS AND DISCOURSE Heejung Kang, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor and Program Coordinator Stephen Slottow, Minor Professor Josef Banowetz, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Interim Chair of Piano Jessie Eschbach, Chair of Keyboard Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrill, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kang, Heejung, Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43: Analysis and Discourse. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2004, 169 pp., 40 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 39 titles. This dissertation on Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43 is divided into four parts: 1) historical background and the state of the sources, 2) analysis, 3) semantic issues related to analysis (discourse), and 4) performance and analysis. The analytical study, which constitutes the main body of this research, demonstrates how Rachmaninoff organically produces the variations in relation to the theme, designs the large-scale tonal and formal organization, and unifies the theme and variations as a whole. The selected analytical approach is linear in orientation - that is, Schenkerian. In the course of the analysis, close attention is paid to motivic detail; the analytical chapter carefully examines how the tonal structure and motivic elements in the theme are transformed, repeated, concealed, and expanded throughout the variations. As documented by a study of the manuscripts, the analysis also facilitates insight into the genesis and structure of the Rhapsody. -

An Interview with Robert Shaw: Reflections at Eighty

An Interview with Robert Shaw: Reflections at Eighty by Jeffrey Baxter RobertShaw .Robert Shaw's distinguished career began in New York City In 1979, Shaw was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to in 1938, where he prepared choruses for such renowned con the National Council on the Arts and he was a 1991 recipient of ductors as Fred Waring, Arturo Toscanini, and Bruno Walter. the Kennedy Center Honors, the nation's highest award given to In 1949 he formed the Robert Shaw Chorale, which for two artists. Musical America, the international directory of the per decades reigned as America's premier touring choir. Under the forming arts, named him Musician of the Year for 1992, and auspices ofthe U.S. State Department, the Chorale performed during the same year he was awarded the National Medal ofthe in thirty countries throughout Europe, the Soviet Union, the Arts in a White House ceremony. He was the 1993 recipient of Middle East, and Latin America. During this period Shaw also the Conductors' Guild TheodoreThomas Award, in recognition served as Music Director ofthe San Diego Symphony and then ofhis outstanding achievement in conducting and his contribu as Associate Conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, working tions to the education and training ofyoung conductors. closely with George Szell for eleven years. He served as Music A regular guest conductor ofmajor orchestras in this country Director of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra from 1967 to and abroad, Shaw also is in demand as a teacher and lecturer at 1988, during which time the orchestra garnered widespread leading U.S. -

Myra Hess Had to Wait for Her Ultimate Breakthrough in Her English Homeland; for This Reason, She Initially Had to Earn Her Living by Teaching

Hess, Myra Irene Scharrer. However, Myra Hess had to wait for her ultimate breakthrough in her English homeland; for this reason, she initially had to earn her living by teaching. Her first major success abroad was her debut in Amster- dam, where she performed Schumann's Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54 with the Concertgebouw Orchestra un- der Willem Mengelberg in 1912. In 1922 followed her de- but in New York, where she was celebrated with equal en- thusiasm. Her career advanced rapidly from that point onwards, and she rose to the position of one of the most successful pianists in her homeland during the ensuing years. During the 1930s, she undertook extended concert tours throughout all of Europe, including the Scandinavi- an countries, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Rumania, Tur- key, Yugoslavia, Germany, France and Holland. At the be- ginning of the Second World War, when all of London's concert halls were closed, she founded the legendary "Lunchtime Recitals" at the National Gallery, offering the London public a broad spectrum of high-quality pro- grammes with both young and established musicians. She herself performed at the National Gallery 146 times. The concerts were held without interruption until 10 Ap- Die Pianistin Myra Hess ril 1946. In 1941 Myra Hess was honoured with the title "Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire" Myra Hess for her special efforts on behalf of musical life in her ho- meland. After the Second World War, the meanwhile fa- * 25 February 1890 in Hampstead (im heutigen mous pianist regularly gave concerts in her native count- Londoner Stadtbezirk Camden), England ry and in the USA, where she enjoyed great popularity. -

L'importanza Dell'etica Nella Grande Interpretazione Musicale: Testimonianze E Incontri Con Celebri Pianisti

L’importanza dell’etica nella grande interpretazione musicale: testimonianze e incontri con celebri pianisti Kazimierz Morski Pianista. Direttore d’orchestra. Catedratico di Scienze Musicali Università Slesiana di Katowice Università Autonoma di Madrid1 Università di Roma 2 “Tor Vergata”2 Sintesi. Il saggio è frutto di personali esperienze e di considerazioni sorte nell’accostarsi a grandi personaggi della musica, in questo caso pianistica, il cui impegno etico-estetico sta alla base della profonda grandezza di esecuzioni divenute ormai patrimonio storico. Modelli in tal senso sono stati Neuhaus, Benedetti Michelangeli o Arrau per chi, come me, ha potuto incontrarli o sentirli in concerto e si trova oggi a porli nella prospettiva storica assieme ad altri artisti del mondo compositivo ed interpretativo. Nonostante le differenze e le soggettive concezioni di approccio alla musica, dal concertismo puro, all’impegno didattico, alla riflessione teorica, quanto appare nelle loro realizzazioni è un atteggiamento umano e culturale spesso celato da un nobile riserbo, segno irripetibile dell’arte nella sua essenza. Di qui l’affermazione della necessaria componente etica nell’ambito estetico delle grandi interpretazioni, sia in relazione all’originaria idea creativa che al suo mutare a seconda del gusto e delle epoche. Le testimonianze addotte conducono a profonde considerazioni sul rapporto tra l’elemento ontologico relativo soprattutto alla creatività e quello fenomenologico soggetto alle continue variazioni del modo di sentire. Parole chiave. idea creativa - interpretazione ideale - esecuzione - concertismo - pianisti - personalità artistica - virtuosismo - espressione- tradizione - didattica - etica - estetica - esperienze – testimonianze. Abstract. This essay is the result of personal experiences and considerations while addressing the fate of great musicians – in this case of piano players - whose ethic-aesthetic commitment is behind the greatness of certain interpretations that have become part our cultural heritage. -

2017-2018 Master Class-Leon Fleisher

Welcome to the 2017-2018 season. The talented students and extraordinary faculty of the Lynn LEON FLEISHER MASTER CLASS Conservatory of Music take this opportunity to share with you the beautiful world of music. Your Wednesday, January 24, 2018 at 7:00 pm ongoing support ensures our place among the premier conservatories Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall of the world and a staple of our community. - Jon Robertson, dean PROGRAM There are a number of ways by which you can help us fulfill our mission: Friends of the Conservatory of Music Sonata Op. 2 No. 2 in A Major Ludwig van Beethoven Lynn University’s Friends of the Conservatory of Music is a IV Rondo: Grazioso (1770-1827) volunteer organization that supports high-quality music education through fundraising and community outreach. Raising more than $2 million since 2003, the Friends support Lynn’s effort to provide Chance Israel, piano free tuition scholarships and room and board to all Conservatory of Music students. The group also raises money for the Dean’s Discretionary Fund, which supports the immediate needs of the university’s music performance students. This is accomplished through annual gifts and special events, such as outreach concerts and the annual Gingerbread Holiday Concert. To learn more about joining the Friends and its many benefits, Scherzo No. 4 in E Major Frederic Chopin such as complimentary concert admission, visit Give.lynn.edu/support-music. (1810-1849) The Leadership Society of Lynn University Meiyu Wu, piano The Leadership Society is the premier annual giving society for donors who are committed to ensuring a standard of excellence at Lynn for all students. -

TCB Groove Program

www.piccolotheatre.com 224-420-2223 T-F 10A-5P 37 PLAYS IN 80-90 MINUTES! APRIL 7- MAY 14! SAVE THE DATE! NOVEMBER 10, 11, & 12 APRIL 21 7:30P APRIL 22 5:00P APRIL 23 2:00P NICHOLS CONCERT HALL BENITO JUAREZ ST. CHRYSOSTOM’S Join us for the powerful polyphony of MUSIC INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO COMMUNITY ACADEMY EPISCOPAL CHURCH G.F. Handel's As pants the hart, 1490 CHICAGO AVE PERFORMING ARTS CENTER 1424 N DEARBORN ST. EVANSTON, IL 60201 1450 W CERMAK RD CHICAGO, IL 60610 Domenico Scarlatti's Stabat mater, TICKETS $10-$40 CHICAGO, IL 60608 TICKETS $10-$40 and J.S. Bach's Singet dem Herrn. FREE ADMISSION Dear friends, Last fall, Third Coast Baroque’s debut series ¡Sarabanda! focused on examining the African and Latin American folk music roots of the sarabande. Today, we will be following the paths of the chaconne, passacaglia and other ostinato rhythms – with origins similar to the sarabande – as they spread across Europe during the 17th century. With this program that we are calling Groove!, we present those intoxicating rhythms in the fashion and flavor of the different countries where they gained popularity. The great European composers wrote masterpieces using the rhythms of these ancient dances to create immortal pieces of art, but their weight and significance is such that we tend to forget where their origins lie. Bach, Couperin, and Purcell – to name only a few – wrote music for highly sophisticated institutions. Still, through these dance rhythms, they were searching for something similar to what the more ancient civilizations had been striving to attain: a connection to the spiritual world. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

Spleatipiiidiiiiiiiiiiiiiiitilullut Academy

\ ACADEMY & FESTIVAL Faculty Artist Recital Du Huang, Piano Jeffery Meyer, Piano Naomi Niskala, Piano Nathan Knutson, Piano Karen Wilkerson, Mezzo-soprano Cheryl Lemmons, Piano Paul Morton, Trumpet Ray Iwazumi, Violin Ayako Yonetani, Violin Spencer Martin, Viola Bjérling Recital Hall Schaefer Fine Arts Center Gustavus Adolphus College Sunday, June 29, 2008 8:00 PM This program has been sponsored by the Wenger Corporation SPLEATIPIIIDIIIIIIIIIIIIIIITILULLUT Program at Sonata in One Movement for 2 Pianos 8 Hands Bedrich Smetana (1824—1884) Du Huang, Jeffery Meyer, Naomi Niskala, and Nathan Knutson, Piano Greeting Leonard Bernstein (1918-1884) In the corner Modeste Mussorgsky (1839-1881) The Green-Eyed Dragon Greatrex Newman (1892—1984) Wolseley Charles CET Holding Each Other Gene Scheer God Bless the Child Billie Holiday With: Paul Morton, Trumpet (1915—1959) Arthur Herzog Jr. (1927—1983) Karen Wilkerson, Mezzo-soprano Cheryl Lemmons, Piano EPTEC Sonata for Piano and Violin in F major, Op. 24 Beethoven "Spring" (1770—1827) I. Allegro Il. Adagio molto espressivo CELT Ill. Scherzo: Allegro molto IV. Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo Ray Iwazumi, Violin Naomi Niskala, Piano Passacaglia in g minor George Frideric Handel (1685—1759) Arr. Johan Halvorsen (1864—1935) Ayako Yonetani, Violin Spencer Martin, Viola CEFCFEFEFEECEC Pianist Du Huang has presented solo performances at the Grosser Saal of the Konzerthaus in Vienna, Salle Cortot in Paris, Shanghai Music Hall and Beijing Music Hall in China, and numerous concert venues in Czech Republic. Huang also performs actively as a member of the Unison Piano Duo, their concert performances have been broadcasted by Minnesota Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Radio, and Iowa Public Television.