5. PART-2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of Wild Brook Trout Populations in Vermont Streams

Evaluation of Wild Brook Trout Populations in Vermont Streams Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department Annual Report State: Vermont Project No.: F-36-R-19 Grant Title: Inland Waters Fisheries and Habitat Management Study No. I Study Title: Salmonid Inventory and Management Period Covered: July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2017 SUMMARY Wild brook trout populations in Vermont streams appeared to be relatively stable over a period of five decades as evidenced in this evaluation of 150 sites. Present-day brook trout populations sampled in 138 streams within 17 watersheds were characterized by abundant natural reproduction and multiple age-classes, including the contribution of older, larger fish. While most population measures were consistent between the two time periods, significantly higher densities of young-of-year brook trout were observed in current populations which may reflect improved environmental protections initiated since the 1950s. A decline in sympatric brown trout and rainbow trout sites also suggest that non-native trout populations have not appreciably expanded over the past 50 years. INTRODUCTION Brook trout Salvelinus fontinalis are native to Vermont and are widely distributed throughout the state (VDFW 1993, EBTJV). It is the fish species most likely to be encountered in small upland streams, particularly at higher elevations where it is often the only fish species inhabiting these waters. In addition to being an indicator of high quality aquatic habitat, brook trout are also a favorite of Vermont anglers. Statewide angler surveys conducted in 1991, 2000 and 2010, revealed it was the fish species most preferred by Vermont resident anglers (Claussen et al. 1992, Kuentzel 2001, Connelly and Knuth 2010). -

Penobscot Rivershed with Licensed Dischargers and Critical Salmon

0# North West Branch St John T11 R15 WELS T11 R17 WELS T11 R16 WELS T11 R14 WELS T11 R13 WELS T11 R12 WELS T11 R11 WELS T11 R10 WELS T11 R9 WELS T11 R8 WELS Aroostook River Oxbow Smith Farm DamXW St John River T11 R7 WELS Garfield Plt T11 R4 WELS Chapman Ashland Machias River Stream Carry Brook Chemquasabamticook Stream Squa Pan Stream XW Daaquam River XW Whitney Bk Dam Mars Hill Squa Pan Dam Burntland Stream DamXW Westfield Prestile Stream Presque Isle Stream FRESH WAY, INC Allagash River South Branch Machias River Big Ten Twp T10 R16 WELS T10 R15 WELS T10 R14 WELS T10 R13 WELS T10 R12 WELS T10 R11 WELS T10 R10 WELS T10 R9 WELS T10 R8 WELS 0# MARS HILL UTILITY DISTRICT T10 R3 WELS Water District Resevoir Dam T10 R7 WELS T10 R6 WELS Masardis Squapan Twp XW Mars Hill DamXW Mule Brook Penobscot RiverYosungs Lakeh DamXWed0# Southwest Branch St John Blackwater River West Branch Presque Isle Strea Allagash River North Branch Blackwater River East Branch Presque Isle Strea Blaine Churchill Lake DamXW Southwest Branch St John E Twp XW Robinson Dam Prestile Stream S Otter Brook L Saint Croix Stream Cox Patent E with Licensed Dischargers and W Snare Brook T9 R8 WELS 8 T9 R17 WELS T9 R16 WELS T9 R15 WELS T9 R14 WELS 1 T9 R12 WELS T9 R11 WELS T9 R10 WELS T9 R9 WELS Mooseleuk Stream Oxbow Plt R T9 R13 WELS Houlton Brook T9 R7 WELS Aroostook River T9 R4 WELS T9 R3 WELS 9 Chandler Stream Bridgewater T T9 R5 WELS TD R2 WELS Baker Branch Critical UmScolcus Stream lmon Habitat Overlay South Branch Russell Brook Aikens Brook West Branch Umcolcus Steam LaPomkeag Stream West Branch Umcolcus Stream Tie Camp Brook Soper Brook Beaver Brook Munsungan Stream S L T8 R18 WELS T8 R17 WELS T8 R16 WELS T8 R15 WELS T8 R14 WELS Eagle Lake Twp T8 R10 WELS East Branch Howe Brook E Soper Mountain Twp T8 R11 WELS T8 R9 WELS T8 R8 WELS Bloody Brook Saint Croix Stream North Branch Meduxnekeag River W 9 Turner Brook Allagash Stream Millinocket Stream T8 R7 WELS T8 R6 WELS T8 R5 WELS Saint Croix Twp T8 R3 WELS 1 Monticello R Desolation Brook 8 St Francis Brook TC R2 WELS MONTICELLO HOUSING CORP. -

Norton Town Plan

Norton Town Plan Adopted: July 11, 2019 Norton Selectboard Daniel Keenan Christopher Fletcher Franklin Henry Norton Planning Commission Tonilyn Fletcher Suzanne Isabelle Gina Vigneault Patricia Whitney Daniel Keenan (ex officio) Table of Contents Norton Town Plan ................................................................................................................ i I. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 II. Land Use ........................................................................................................................ 4 III. Employment/Economic Opportunity .......................................................................... 12 IV. Transportation ............................................................................................................. 15 V. Community Facilities & Utilities ................................................................................. 18 VI. Education .................................................................................................................... 27 VII. Natural, Scenic and Historic Resources .................................................................... 27 VIII. Energy ...................................................................................................................... 32 IX. Housing ....................................................................................................................... 34 X. Flood Resilience .......................................................................................................... -

GOLD PLACER DEPOSITS of the EASTERN TOWNSHIPS, PART E PROVINCE of QUEBEC, CANADA Department of Mines and Fisheries Honourable ONESIME GAGNON, Minister L.-A

RASM 1935-E(A) GOLD PLACER DEPOSITS OF THE EASTERN TOWNSHIPS, PART E PROVINCE OF QUEBEC, CANADA Department of Mines and Fisheries Honourable ONESIME GAGNON, Minister L.-A. RICHARD. Deputy-Minister BUREAU OF MINES A.-0. DUFRESNE, Director ANNUAL REPORT of the QUEBEC BUREAU OF MINES for the year 1935 JOHN A. DRESSER, Directing Geologist PART E Gold Placer Deposits of the Eastern Townships by H. W. McGerrigle QUEBEC REDEMPTI PARADIS PRINTER TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING 1936 PROVINCE OF QUEBEC, CANADA Department of Mines and Fisheries Honourable ONESIME GAGNON. Minister L.-A. RICHARD. Deputy-Minister BUREAU OF MINES A.-O. DUFRESNE. Director ANNUAL REPORT of the QUEBEC BUREAU OF MINES for the year 1935 JOHN A. DRESSER, Directing Geologist PART E Gold Placer Deposits of the Eastern Townships by H. W. MeGerrigle QUEBEe RÉDEMPTI PARADIS • PRINTER TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING 1936 GOLD PLACER DEPOSITS OF THE EASTERN TOWNSHIPS by H. W. McGerrigle TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 5 Scope of report and method of work 5 Acknowledgments 6 Summary 6 Previous work . 7 Bibliography 9 DESCRIPTION OF PLACER LOCALITIES 11 Ascot township 11 Felton brook 12 Grass Island brook . 13 Auckland township. 18 Bury township .. 19 Ditton area . 20 General 20 Summary of topography and geology . 20 Table of formations 21 IIistory of development and production 21 Dudswell township . 23 Hatley township . 23 Horton township. 24 Ireland township. 25 Lamhton township . 26 Leeds township . 29 Magog township . 29 Orford township . 29 Shipton township 31 Moe and adjacent rivers 33 Moe river . 33 Victoria river 36 Stoke Mountain area . -

Upper Connecticut River Paddler's Trail Strategic Assessment

VERMONT RIVER CONSERVANCY: Upper Connecticut River Paddler's Trail Strategic Assessment Prepared for The Vermont River Conservancy. 29 Main St. Suite 11 Montpelier, Vermont 05602 Prepared by Noah Pollock 55 Harrison Ave Burlington, Vermont 05401 (802) 540-0319 • [email protected] Updated May 12th, 2009 CONNECTICUT RIVER WATER TRAIL STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................2 Results of the Stakeholder Review and Analysis .............................................................................5 Summary of Connecticut River Paddler's Trail Planning Documents .........................................9 Campsite and Access Point Inventory and Gap Analysis .............................................................14 Conclusions and Recommendations ................................................................................................29 Appendix A: Connecticut River Primitive Campsites and Access Meeting Notes ...................32 Appendix B: Upper Valley Land Trust Campsite Monitoring Checklist ....................................35 Appendix C: Comprehensive List of Campsites and Access Points .........................................36 Appendix D: Example Stewardship Signage .................................................................................39 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Northern Forest Canoe Trail Railroad Trestle ................................................................2 -

Environmental Assessment Northern Border Remote Radio Link Pilot Project Essex and Orleans Counties, Vermont

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT NORTHERN BORDER REMOTE RADIO LINK PILOT PROJECT ESSEX AND ORLEANS COUNTIES, VERMONT February 2019 Lead Agency: U.S. Customs and Border Protection 24000 Avila Road, Suite 5020 Laguna Niguel, California 92677 Prepared by: Gulf South Research Corporation 8081 Innovation Park Drive Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70820 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background and Purpose and Need The area near the U.S./Canada International border in Vermont is extremely remote and contains dense forest and steep terrain intersected by numerous streams, lakes, and bogs. These conditions make it very difficult for U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) agents to patrol the area and communicate with each other and station personnel while on patrol. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Science and Technology Directorate (S&T), has developed a prototypical Remote Radio Link Project that includes the installation of a buried communications cable to enhance the communications capability and safety of Border Patrol agents who are conducting enforcement activities in these areas. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is assisting S&T in developing this Environmental Assessment (EA) to address the proposed installation and operation of the pilot project. The purpose of this pilot project is to determine the effectiveness of this type of remote radio link system in four-season weather. The need for the project is to identify such reliable communication methods that can enhance USBP enforcement activities and agent safety. Proposed Action The Proposed Action includes the installation, operation, and maintenance of a Remote Radio Link Pilot Project along the U.S./Canada International border west of Norton, Vermont. -

!"`$ Ik Ik Ie !"B$ Ie Im Ih Im !"`$ !"A$ !"A$ Ie

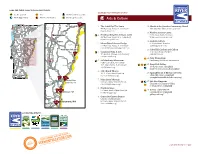

Ij !Alburgh ?È ?Ò ?Ö Jay !( Newport ?Ý ?Î Q` !!( ?Ú !( ! ?ê ?Ò Enosburg Colebrook, NH Falls ?É North Hero ! !( St. Albans ?à !"`$ ?Ö ?Ò Ie ?Ø ?£ ?Ð ?Ý ?f !"a$ ?u Jeffersonville LOOK FOR THESE !(ICONSMilton TO?Ð PLAN YOUR!( TRAVEL: CONNECTICUT RIVER BYWAY Scenic Lookout ?é Free Motor?¦ CoachIk Accessible! East Burke Photo Opportunity Activities for Families?¤ Handicap Accessible?Ý ?É Lyndonville ! ?Ö Hardwick ?Î Arts & Culture !( Lancaster, NH !!P ?¡ ! !!( StoweIj 1-5 Ie !Alburgh ?Ò ?È BurlingtonJay !( Newport ?£ ?Ö !( ?Ý ?Î Q` St. Johnsbury! 1. The Artful Eye/The Annex 10. Murals at the Quechee Community Church !( ?Ú ! Enosburg Colebrook, NH Waterbury ?¨ ?ê ?Ò Falls ! ?É Center 443 Railroad Street, St. Johnsbury 1905 Quechee Main Street., Quechee North Hero ! !( St. Albans ?à !"`$ !"`$ ?Ö ?Ò Ie ?Ø Ie !"b$ theartfuleye.com ?£ ?Ð ?Ý ?f !"a$ ! Ie Jeffersonville Waterbury?u 11. Windsor Auction Center !( MiltonIm?Ð !( ?Þ ! ?é ?¦ Ik ! East Burke 2. Northeast Kingdom Artisans Guild 64/66 Main Street, Windsor ?¤ ?É ?É Lyndonville ! ?Ý ?Ö Hardwick ?Î Montpelier !( Lancaster, NH! ?ý !!P ?¡ 430 Railroad Street #2, St. Johnsbury windsorauctioncenter.com/ Stowe !!( Ie ?Ë (\! Burlington ?£ St. Johnsbury! ! Waterbury ?¨ Center nekartisansguild.com !!"`$FerrisburghIe !"b$ Waterbury! Ie Im ?Þ ?§ ?¡ 12. Arabella Gallery ?É Montpelier ?Ë (\! ?ý !( Waitsfield !P Barre ! Ferrisburgh ?§ ?¡ !P 3. Moose River Lake and Lodge 65 Main Street, Windsor !( Vergennes!( Waitsfield Barre !( Vergennes ?£ Wells River, VT ! Wells River, VT ! ?ª ?§ ?Á ?£ 370 Railroad Street, St. Johnsbury arabellagallery.com/ ?§ ?Þ ?¢§ ?Ù NNorthorth HHaverhill,averhill, NNHH ! C ?ª !( Chimney Point Middlebury ?É ? ?¬ ?æ ! ?¡ Q{ ?Á mooseriverlakeandlodgestore.com ?£ ?Ü ?¢ ?Ù ! 13. -

Taconic Physiography

Bulletin No. 272 ' Series B, Descriptive Geology, 74 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR . UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR 4 t TACONIC PHYSIOGRAPHY BY T. NELSON DALE WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1905 CONTENTS. Page. Letter of transinittal......................................._......--..... 7 Introduction..........I..................................................... 9 Literature...........:.......................... ........................... 9 Land form __._..___.._.___________..___._____......__..__...._..._--..-..... 18 Green Mountain Range ..................... .......................... 18 Taconic Range .............................'............:.............. 19 Transverse valleys._-_-_.-..._.-......-....___-..-___-_....--_.-.._-- 19 Longitudinal valleys ............................................. ^...... 20 Bensselaer Plateau .................................................... 20 Hudson-Champlain valley................ ..-,..-.-.--.----.-..-...... 21 The Taconic landscape..................................................... 21 The lakes............................................................ 22 Topographic types .............,.....:..............'.................... 23 Plateau type ...--....---....-.-.-.-.--....-...... --.---.-.-..-.--... 23 Taconic type ...-..........-........-----............--......----.-.-- 28 Hudson-Champlain type ......................"...............--....... 23 Rock material..........................'.......'..---..-.....-...-.--.-.-. 23 Harder rocks ....---...............-.-.....-.-...--.-......... -

Cavendish Town Plan Select Board Hearing Draft January 2018

Cavendish Town Plan Select Board Hearing Draft January 2018 Town of Cavendish P.O. Box 126 Cavendish, Vermont 05142 (802) 226-7292 Document History • Planning Commission hearing and approval of re-adoption of Town Plan with inclusion of Visual Access Map - February 22, 2012 • Select board review of Planning Commission proposed re-adopted town plan with visual access map - April 9, 2012 • Select board review of town plan draft and approval of SB proposed minor modifications to plan – May 14, 2012 • Planning Commission hearing for re-adoption of Town Plan with Select board proposed minor modifications – June 6, 2012 • Planning Commission Approval of Re-adoption of Town Plan with minor modifications – June 6, 2012 • 1st Select board hearing for re-adoption of town plan with minor modifications – June 11, 2012 • 2nd Select board Hearing for re-adoption of Town Plan with minor modifications – August 20, 2012 • Cavendish Town Plan Re-adopted by Australian ballot at Special Town Meeting – August 28, 2012 • Confirmation of Planning Process and Act 200 Approval by the Southern Windsor County Regional Planning Commission – November 27, 2012 • Planning Commission is prepared updates in 2016-2017 This report was developed in 2016 and 2017 for the Town of Cavendish with assistance from the Southern Windsor County Regional Planning Commission, Ascutney, VT. Financial support for undertaking this revision was provided, in part, by a Municipal Planning Grant from the Vermont Agency of Commerce and Community Development. ii Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Planning Process Summary................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Community and Demographic Trends ............................................................................ -

The Geology of the Lyndonville Area, Vermont

THE GEOLOGY OF THE LYNDONVILLE AREA, VERMONT By JOHN G. DENNIS VERMONT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. DOLL, Stale Geologist Published by VERMONT DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION MONTPELIER, VERMONT BULLETIN NO. 8 1956 Lake Willoughby, seen from its north shore. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ......................... 7 INTRODUCTION 8 Location 8 Geologic Setting ..................... 8 Previous Work ...................... 8 Purpose of Study ..................... 9 Method of Study 10 Acknowledgments . 11 Physiography ...................... 11 STRATIGRAPHY ....................... 16 Lithologic Descriptions .................. 16 Waits River Formation ................. 16 General Statement .................. 16 Distribution ..................... 16 Age 17 Lithological Detail .................. 17 Gile Mountain Formation ................ 19 General Statement .................. 19 Distribution ..................... 20 Lithologic Detail ................... 20 The Waits River /Gile Mountain Contact ........ 22 Age........................... 23 Preliminary Remarks .................. 23 Early Work ...................... 23 Richardson's Work in Eastern Vermont .......... 25 Recent Detailed Mapping in the Waits River Formation. 26 Detailed Work in Canada ................ 28 Relationships in the Connecticut River Valley, Vermont and New Hampshire ................... 30 Summary of Presently Held Opinions ........... 32 Discussion ....................... 32 Conclusions ...................... 33 STRUCTURE 34 Introduction and Structural Setting 34 Terminology ...................... -

Okemo State Forest - Healdville Trail Forest - Healdville Okemo State B

OKEMO STATE FOREST - HEALDVILLE TRAIL North 3000 OKEMO MOUNTAIN RESORT SKI LEASEHOLD AREA OKEMO MOUNTAIN ROAD (paved) 2500 2000 Coleman Brook HEALDVILLE TRAIL 1500 to Ludlow - 5 miles STATION RD railroad tracks HEALDVILLE RD HEALDVILLE VERMONT UTTERMILK F 103 B AL LS RD to Rutland - 16 miles Buttermilk Falls 0 500 1000 2000 3000 feet 1500 LEGEND Foot trail Vista Town highway State highway Lookout tower FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION State forest highway (not maintained Parking area (not maintained in winter) VERMONT in winter) Gate, barricade Stream AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES Ski chairlift Ski area leasehold boundary 02/2013-ephelps Healdville Trail - Okemo State Forest the property in 1935. Construction projects by the CCC The Healdville Trail climbs from the base to the include the fire tower, a ranger’s cabin and an automobile summit of Okemo Mountain in Ludlow and Mount Holly. access road. The majority of Okemo Mountain Resort’s Highlights of this trail include the former fire lookout ski terrain is located within a leased portion of Okemo tower on the summit and a vista along the trail with State Forest. Okemo State Forest is managed for Okemo views to the north and west. Crews from the Vermont multiple uses under a long-term management plan; these Youth Conservation Corps constructed the trail under the uses include forest products, recreation and wildlife direction of the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks habitat. Okemo State Forest provides an important State Forest and Recreation during the summers of 1991-1993. wildlife corridor between Green Mountain National Forest lands to the south and Coolidge State Forest to the Trail Facts north. -

122 Fish Management Rule Annotated

APPENDIX 122 TITLE 10 Conservation and Development APPENDIX CHAPTER 2. FISH Subchapter 2. Seasons, Waters, and Limits § 122. Fish Management Regulation. 1.0 Authority (a) This rule is adopted pursuant to 10 V.S.A. §4081(b). In adopting this rule, the Fish and Wildlife Board is following the policy established by the General Assembly that the protection, propagation, control, management, and conservation of fish, wildlife and fur-bearing animals in this state is in the interest of the public welfare and that the safeguarding of this valuable resource for the people of the state requires a constant and continual vigilance. (b) In accordance with 10 V.S.A. §4082, this rule is designed to maintain the best health, population and utilization levels of Vermont’s fisheries. (c) In accordance with 10 V.S.A. §4083, this rule establishes open seasons; establishes daily, season, possession limits and size limits; prescribes the manner and means of taking fish; and prescribes the manner of transportation and exportation of fish. 2.0 Purpose It is the policy of the state that the protection, propagation control, management and conservation of fish, wildlife, and fur-bearing animals in this state is in the interest of the public welfare, and that safeguarding of this valuable resource for the people of the state requires a constant and continual vigilance. 3.0 Open-Water Fishing, legal methods of taking fish 3.1 Definitions (a) Department – Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife. (b) Commissioner –Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife Commissioner. (c) Open-water fishing –Fishing by means of hook and line in hand or attached to a rod or other device in open water.