The Response of Several Citrus Genotypes to High-Salinity Irrigation Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Responsive Online System for Acta Horticulturae Submission and Review

International Society for Horticultural Science ROSA - Responsive Online System for Acta Horticulturae submission and review This submission belongs to: XV Eucarpia Symposium on Fruit Breeding and Genetics Acta Below is the abstract for symposium nr 620, abstract nr 135: Horticulturae Home Title: Login Logout Improvement of salt tolerance and resistance to Phytophthora Status gummosis in citrus rootstocks through controlled hybridization ISHS Home Author(s): ISHS Contact Anas Fadli, UR APCRP, INRA, BP 257, Kenitra, Morocco; ISHS online [email protected] (presenting author) submission Dr. Samia Lotfy, UR APCRP, INRA, BP 257, Kenitra, Morocco; and review [email protected] (co-author) tool Mr. Abdelhak Talha, UR APCRP , INRA, BP 257, Kenitra, Morocco; homepage [email protected] (co-author) Calendar Dr. Driss Iraqi, UR de Biotechnologie, INRA, BP 415, Rabat, Morocco; of [email protected] (co-author) Symposia Dr. María Angeles Moreno, Estación Experimental de Aula Dei, CSIC, Authors Av. Montañana 1.005, Zaragoza, Spain; [email protected] (co- Guide author) Prof. Dr . Rachid Benkirane, Laboratoire BBPP, Département de Biologie, Faculté des Sciences, Université Ibn Tofail, Kenitra, Morocco; [email protected] (co-author) Dr. Hamid Benyahia, UR APCRP, INRA, BP 257, Kenitra, Morocco; [email protected] (co-author) Preferred presentation method: Poster Abstract body text: The sustainability of Mediterranean citriculture depends largely on the use of rootstocks that provide a better adaptation to biotic and abiotic constraints, as well as a good graft-compatibility with commercial cultivars. In the absence of rootstocks meeting all these criteria, the management of the available diversity and the selection of the desirable traits are necessary. -

Citrus from Seed?

Which citrus fruits will come true to type Orogrande, Tomatera, Fina, Nour, Hernandina, Clementard.) from seed? Ellendale Tom McClendon writes in Hardy Citrus Encore for the South East: Fortune Fremont (50% monoembryonic) “Most common citrus such as oranges, Temple grapefruit, lemons and most mandarins Ugli Umatilla are polyembryonic and will come true to Wilking type. Because most citrus have this trait, Highly polyembryonic citrus types : will mostly hybridization can be very difficult to produce nucellar polyembryonic seeds that will grow true to type. achieve…. This unique characteristic Citrus × aurantiifolia Mexican lime (Key lime, West allows amateurs to grow citrus from seed, Indian lime) something you can’t do with, say, Citrus × insitorum (×Citroncirus webberii) Citranges, such as Rusk, Troyer etc. apples.” [12*] Citrus × jambhiri ‘Rough lemon’, ‘Rangpur’ lime, ‘Otaheite’ lime Monoembryonic (don’t come true) Citrus × limettioides Palestine lime (Indian sweet lime) Citrus × microcarpa ‘Calamondin’ Meyer Lemon Citrus × paradisi Grapefruit (Marsh, Star Ruby, Nagami Kumquat Redblush, Chironja, Smooth Flat Seville) Marumi Kumquat Citrus × sinensis Sweet oranges (Blonde, navel and Pummelos blood oranges) Temple Tangor Citrus amblycarpa 'Nasnaran' mandarin Clementine Mandarin Citrus depressa ‘Shekwasha’ mandarin Citrus karna ‘Karna’, ‘Khatta’ Poncirus Trifoliata Citrus kinokuni ‘Kishu mandarin’ Citrus lycopersicaeformis ‘Kokni’ or ‘Monkey mandarin’ Polyembryonic (come true) Citrus macrophylla ‘Alemow’ Most Oranges Citrus reshni ‘Cleopatra’ mandarin Changshou Kumquat Citrus sunki (Citrus reticulata var. austera) Sour mandarin Meiwa Kumquat (mostly polyembryonic) Citrus trifoliata (Poncirus trifoliata) Trifoliate orange Most Satsumas and Tangerines The following mandarin varieties are polyembryonic: Most Lemons Dancy Most Limes Emperor Grapefruits Empress Tangelos Fairchild Kinnow Highly monoembryonic citrus types: Mediterranean (Avana, Tardivo di Ciaculli) Will produce zygotic monoembryonic seeds that will not Naartje come true to type. -

Reaction of Types of Citrus As Scion and As Rootstock to Xyloporosis Virus

ARY A. SALIBE and SYLVIO MOREIRA Reaction of Types of Citrus as Scion and as Rootstock to Xyloporosis Virus THEVIRUS of xyloporosis (cachexia) (2,4, 10) is widespread in many commercial varieties of citrus ( 1, 5, 6, 8).For this reason, it is of special interest to know the reaction between it and various types of citrus that are presently used as rootstocks or may eventually be so used. This paper reports the results of tests conducted to determine this reaction for a number of different types of citrus. Materials and Methods In September, 1960, 2-year-old Cleopatra mandarin [Citrus reshni (Engl.) Hort. ex Tanaka] seedlings in the nursery were inoculated with xyloporosis virus by budding each seedling with three buds from a single old-line Bargo sweet orange [C. sinensis (L.) Osbeck] tree on Dancy tan- gerine (C. tangerina Hort. ex Tanaka) rootstock exhibiting the gummy- peg and wood-pitting type of xyloporosis symptoms. This tree was known to be carrying both xyloporosis and tristeza viruses but neither psorosis nor exocortis viruses. Two months later, each of two of these seedlings was budded just above the inoculating bud with one or another of 122 different types of citrus, each bud being taken from a tree of a nucellar line, except in the case of the monoembryonic types. Identical numbers of non-inocu- lated Cleopatra mandarin seedlings were budded with these citrus types to serve as control plants. All seedlings were cut back to allow the buds to sprout. They were inspected periodically by taking out a strip of bark at the bud-union, the last inspection being made 33 months after inocula- tion. -

Asian Citrus Psyllid Control Program in the Continental United States

United States Department of Agriculture Asian Citrus Psyllid Marketing and Regulatory Control Program in the Programs Animal and Continental Plant Health Inspection Service United States and Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment August 2010 Asian Citrus Psyllid Control Program in the Continental United States and Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment August 2010 Agency Contact: Osama El-Lissy Director, Emergency Management Emergency and Domestic Programs Animal Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd. Unit 134 Riverdale, MD 20737 __________________________________________________________ The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’S TARGET Center at (202) 720–2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326–W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250–9410 or call (202) 720–5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. __________________________________________________________ Mention of companies or commercial products in this report does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture over others not mentioned. USDA neither guarantees nor warrants the standard of any product mentioned. Product names are mentioned solely to report factually on available data and to provide specific information. __________________________________________________________ This publication reports research involving pesticides. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. -

Production of Interstocked 'Pera'sweet Orange

Production of interstocked orange nursery trees 5 PRODUCTION OF INTERSTOCKED ‘PERA’ SWEET ORANGE NURSERY TREES ON ‘VOLKAMER’ LEMON AND ‘SWINGLE’ CITRUMELO ROOTSTOCKS Eduardo Augusto Girardi1; Francisco de Assis Alves Mourão Filho2* 1 Treze de Maio, 1299 - Apto. 52 - 13400-300 - Piracicaba, SP - Brasil. 2 USP/ESALQ - Depto. de Produção Vegetal, C.P. 09 - 13418-900 - Piracicaba, SP - Brasil. *Corresponding author <[email protected]> ABSTRACT: Incompatibility among certain citrus scion and rootstock cultivars can be avoided through interstocking. ‘Pera’ sweet orange (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck) nursery tree production was evaluated on ‘Swingle’ citrumelo (Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf x Citrus paradisi Macf) and ‘Volkamer’ lemon (Citrus volkameriana Pasquale) incompatible rootstocks, using ‘Valencia’ and ‘Hamlin’ sweet oranges (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck), ‘Sunki’ mandarin (Citrus sunki Hort. ex Tanaka), and ‘Cleopatra’ mandarin (Citrus reshni Hort. ex Tanaka) as interstocks. Citrus nursery trees interstocked with ‘Pera’ sweet orange on both rootstocks were used as control. ‘Swingle’ citrumelo led to the highest interstock bud take percentage, the greatest interstock height and rootstock diameter, as well as the highest scion and root system dry weight. Percentage of ‘Pera’ sweet orange dormant bud eye was greater for plants budded on ‘Sunki’ mandarin than those budded on ‘Valencia’ sweet orange. No symptoms of incompatibility were observed among any combinations of rootstocks, interstocks and scion. Production cycle can take up to 17 months with higher plant discard. Key words: citrus, incompatibility, interstock, propagation PRODUÇÃO DE MUDAS DE LARANJA ‘PÊRA’ INTERENXERTADAS NOS PORTA-ENXERTOS LIMÃO ‘VOLKAMERIANO’ E CITRUMELO ‘SWINGLE’ RESUMO: A incompatibilidade entre certas variedades de copa e porta-enxertos de citros pode ser evitada através da interenxertia. -

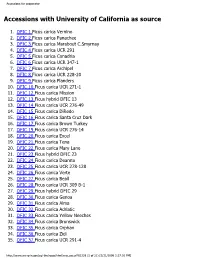

Accessions for Cooperator

Accessions for cooperator Accessions with University of California as source 1. DFIC 1 Ficus carica Vernino 2. DFIC 2 Ficus carica Panachee 3. DFIC 3 Ficus carica Marabout C.Smyrnay 4. DFIC 4 Ficus carica UCR 291 5. DFIC 5 Ficus carica Conadria 6. DFIC 6 Ficus carica UCR 347-1 7. DFIC 7 Ficus carica Archipel 8. DFIC 8 Ficus carica UCR 228-20 9. DFIC 9 Ficus carica Flanders 10. DFIC 10 Ficus carica UCR 271-1 11. DFIC 12 Ficus carica Mission 12. DFIC 13 Ficus hybrid DFIC 13 13. DFIC 14 Ficus carica UCR 276-49 14. DFIC 15 Ficus carica DiRedo 15. DFIC 16 Ficus carica Santa Cruz Dark 16. DFIC 17 Ficus carica Brown Turkey 17. DFIC 19 Ficus carica UCR 276-14 18. DFIC 20 Ficus carica Excel 19. DFIC 21 Ficus carica Tena 20. DFIC 22 Ficus carica Mary Lane 21. DFIC 23 Ficus hybrid DFIC 23 22. DFIC 24 Ficus carica Deanna 23. DFIC 25 Ficus carica UCR 278-128 24. DFIC 26 Ficus carica Verte 25. DFIC 27 Ficus carica Beall 26. DFIC 28 Ficus carica UCR 309 B-1 27. DFIC 29 Ficus hybrid DFIC 29 28. DFIC 30 Ficus carica Genoa 29. DFIC 31 Ficus carica Alma 30. DFIC 32 Ficus carica Adriatic 31. DFIC 33 Ficus carica Yellow Neeches 32. DFIC 34 Ficus carica Brunswick 33. DFIC 35 Ficus carica Orphan 34. DFIC 36 Ficus carica Zidi 35. DFIC 37 Ficus carica UCR 291-4 http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/cno_acc.pl?61329 (1 of 21) [5/31/2009 3:37:10 PM] Accessions for cooperator 36. -

1 Anastrepha Ludens, Mexican Fruit Fly Host List, 2016

Anastrepha ludens, Mexican Fruit Fly Host List, 2016 The berry, fruit, nut or vegetable of the following plant species are now considered regulated (host) articles for Mexican fruit fly and are subject to the requirements of 7 CFR 301.32. In addition, all varieties, subspecies and hybrids of the regulated articles listed are assumed to be suitable hosts unless proven otherwise. Scientific Name Common Name Anacardium occidentale L. Cashew nut Annona cherimola Mill. Cherimoya Annona liebmanniana Baill. Hardshell custard apple Annona reticulata L. Custard apple Annona squamosa L. Sugar apple Capsicum pubescens Ruiz & Pav. Apple chile White sapote, yellow chapote, Casimiroa spp. matasano Citrofortunella microcarpa (bunge) Wijnands Calamondin Citrus aurantium L. Sour orange Italian tangerine, willow-leaf Citrus deliciosa Ten. mandarin Citrus hassakuhort. ex Tanaka Hassaku orange Citrus limetta Risso Sweet lime Citrus limettioides Tanaka Sweet lime Rangpur lime, canton lemon, sour Citrus limonia Osbeck lemon, Mandarin lime Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr. Pummelo, shaddock Citrus medica L. Buddha's-Hand, citron, finger citron Meyer lemon, dwarf lemon, Chinese Citrus meyeri Yu. Tanaka dwarf lemon Citrus nobilis Lour. King orange Citrus paradisi Macfad. Grapefruit Citrus reshni hort. ex. Tanaka Cleopatra mandarin, spice mandarin Citrus reticulata Blanco Mandarin orange, tangerine Common, Kona, blood, baladi, navel, Valencia, corriente or sweet Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck orange 1 Citrus xtangelo J. W. Ingram & H. E. Moore Tangelo Citrus tangerina Tanaka Tangerine, dancy tangerine Citrus unshiu Marcow Satsuma orange, unshiu, mikan Coffea arabica L. Arabian coffee Cydonia oblonga Mill. Quince Diospyros kaki Thunb. Japanese persimmon Inga jinicuil G. Don N/A Inga micheliana Harms N/A Malus pumila Mill. -

Mediterranean Fruit Fly, Ceratitis Capitata, Host List the Berries, Fruit, Nuts and Vegetables of the Listed Plant Species Are Now Considered Host Articles for C

January 2017 Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata, Host List The berries, fruit, nuts and vegetables of the listed plant species are now considered host articles for C. capitata. Unless proven otherwise, all cultivars, varieties, and hybrids of the plant species listed herein are considered suitable hosts of C. capitata. Scientific Name Common Name Acca sellowiana (O. Berg) Burret Pineapple guava Acokanthera oppositifolia (Lam.) Codd Bushman's poison Acokanthera schimperi (A. DC.) Benth. & Hook. f. ex Schweinf. Arrow poison tree Actinidia chinensis Planch Golden kiwifruit Actinidia deliciosa (A. Chev.) C. F. Liang & A. R. Ferguson Kiwifruit Anacardium occidentale L. Cashew1 Annona cherimola Mill. Cherimoya Annona muricata L. Soursop Annona reticulata L. Custard apple Annona senegalensis Pers. Wild custard apple Antiaris toxicaria (Pers.) Lesch. Sackingtree Antidesma venosum E. Mey. ex Tul. Tassel berry Arbutus unedo L. Strawberry tree Arenga pinnata (Wurmb) Merr. Sugar palm Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels Argantree Artabotrys monteiroae Oliv. N/A Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg Breadfruit Averrhoa bilimbi L. Bilimbi Averrhoa carambola L. Starfruit Azima tetracantha Lam. N/A Berberis holstii Engl. N/A Blighia sapida K. D. Koenig Akee Bourreria petiolaris (Lam.) Thulin N/A Brucea antidysenterica J. F. Mill N/A Butia capitata (Mart.) Becc. Jelly palm, coco palm Byrsonima crassifolia (L.) Kunth Golden spoon Calophyllum inophyllum L. Alexandrian laurel Calophyllum tacamahaca Willd. N/A Calotropis procera (Aiton) W. T. Aiton Sodom’s apple milkweed Cananga odorata (Lam.) Hook. f. & Thomson Ylang-ylang Capparicordis crotonoides (Kunth) Iltis & Cornejo N/A Capparis sandwichiana DC. Puapilo Capparis sepiaria L. N/A Capparis spinosa L. Caperbush Capsicum annuum L. Sweet pepper Capsicum baccatum L. -

Diaphorina Citri

EPPO Datasheet: Diaphorina citri Last updated: 2020-09-03 IDENTITY Preferred name: Diaphorina citri Authority: Kuwayana Taxonomic position: Animalia: Arthropoda: Hexapoda: Insecta: Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Liviidae Other scientific names: Euphalerus citri (Kuwayana) Common names: Asian citrus psyllid, citrus psylla, citrus psyllid view more common names online... EPPO Categorization: A1 list view more categorizations online... EU Categorization: A1 Quarantine pest (Annex II A) more photos... EPPO Code: DIAACI Notes on taxonomy and nomenclature Diaphorina citri was recently moved from the family Psyllidae to the family Liviidae. Literature prior to 2015 will probably allocate this species in Psyllidae. HOSTS D. citri is confined to Rutaceae, occurring on wild hosts and on cultivated Citrus, especially grapefruit (Citrus paradisi), lemons (C. limon) and limes (C. aurantiifolia). Murraya paniculata, a rutaceous plant often used for hedges, is a preferred host. Within the EPPO region, host species are generally confined to countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. Host list: Aegle marmelos, Afraegle paniculata, Archidendron lucidum, Atalantia buxifolia, Atalantia, Balsamocitrus dawei, Casimiroa edulis, Citroncirus webberi, Citroncirus, Citrus amblycarpa, Citrus aurantiifolia, Citrus aurantium, Citrus australasica, Citrus australis, Citrus glauca, Citrus halimii, Citrus hassaku, Citrus hystrix, Citrus inodora, Citrus jambhiri, Citrus latipes, Citrus limettioides, Citrus limon, Citrus macrophylla, Citrus maxima, Citrus medica, Citrus paradisi, -

Ceratitis Capitata

EPPO Datasheet: Ceratitis capitata Last updated: 2021-04-28 IDENTITY Preferred name: Ceratitis capitata Authority: (Wiedemann) Taxonomic position: Animalia: Arthropoda: Hexapoda: Insecta: Diptera: Tephritidae Other scientific names: Ceratitis citriperda Macleay, Ceratitis hispanica de Breme, Pardalaspis asparagi Bezzi, Tephritis capitata Wiedemann Common names: Mediterranean fruit fly, medfly view more common names online... EPPO Categorization: A2 list more photos... view more categorizations online... EPPO Code: CERTCA HOSTS C. capitata is a highly polyphagous species whose larvae develop in a very wide range of unrelated fruits. It is recorded from more than 350 different confirmed hosts worldwide, belonging to 70 plant families. In addition, it is associated with a large number of other plant taxa for which the host status is not certain. The USDA Compendium of Fruit Fly Host Information (CoFFHI) (Liquido et al., 2020) provides an extensive host list with detailed references. Host list: Acca sellowiana, Acokanthera abyssinica, Acokanthera oppositifolia, Acokanthera sp., Actinidia chinensis , Actinidia deliciosa, Anacardium occidentale, Annona cherimola, Annona muricata, Annona reticulata, Annona senegalensis, Annona squamosa, Antiaris toxicaria, Antidesma venosum, Arbutus unedo, Arenga pinnata, Argania spinosa, Artabotrys monteiroae, Artocarpus altilis, Asparagus sp., Astropanax volkensii, Atalantia sp., Averrhoa bilimbi, Averrhoa carambola, Azima tetracantha, Berberis holstii, Berchemia discolor, Blighia sapida, Bourreria petiolaris, -

Resistance of Citrus Rootstocks to Phytophthora Citrophthora During

Resistance of Citrus Rootstocks to Phytophthoracitrophthora During Winter Dormancy 0. TUZCU, Associate Professor, Department of Horticulture, University of Qukurova; A. QINAR, Professor, Department of Plant Protection, University of Qukurova; M. 0. GOKSEDEF, Research Plant Pathologist, Regional Plant Protection Institute; M. OZSAN, Professor, Department of Horticulture, University of Qukurova; and M. Bii•iC, Teaching Research Assistant, Department of Plant Protection, University of Qukurova, Adana, Turkey Use of resistant rootstocks has ABSTRACT provided partial success in preventing Tuzcu, 0., Qlnar, A., Gbksedef, M. 0., Ozsan, M., and Bicici, M. 1984. Resistance of citrus gummosis in Turkey. Lemons, although rootstocks to Phytophthora citrophthoraduring winter dormancy. Plant Disease 68:502-505. grafted on resistant sour orange stocks, show high incidence of infection in the Resistance of 70 citrus genera, species, and cultivars to Phytophthora citrophthora was eastern Mediterranean area. This paper investigated during winter dormancy. Aeglopsis chevalieri; Citrus yatsushiro; C. sulcata; C. reports a study of the relative resistance aurantium 'Alibert'and 'Granito'; C. reshni'Kibris';Poncirus trifoliata'Yerli,'"Jacobson,'"SEAB,' of various citrus rootstocks to root rot 'Luisi,'" Rubidoux,' 'Benecke,' 'Rich,' 'Ferme Blanche,' 'Troyer' citrange, and C. ampullaceae were and canker caused by P. citrophihor found to be very resistant. Citrus celebica; C. aurantium 'Cardosi,' 'Santucci,' and 'Curagao'; C. pennivesiculata'CRC'; C. depressa 'CRC'; Carrizo citrange, C. trifoliata 'Menager'; C. wilsonii; and C. webberi 'SRA' were resistant. C. keraji; C. nobilis; C. aurantium 'Azaguie'; C. trifoliata MATERIALS AND METHODS 'Christian,' 'Town,' and 'Yamagushi'; C. assamensis;and C. micrantha were very susceptible. C. Two-year-old seedlings of 70 varieties aurantium 'Yerli' showed medium resistance and 'Okan' was susceptible. -

Variation of Citrus Cultivars in Egypt Assessed

African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 11(91), pp. 15755-15762, 13 November, 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB DOI: 10.5897/AJB12.2259 ISSN 1684–5315 ©2012 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Phytohormones content and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) marker assessment of some Egyptian citrus cultivars Hala F. Ahmed Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted 26 September, 2012 In Egypt, Citrus represents one of the main fruit tree crops for both local and export potentials. In this study, leaf and vegetative bud samples were studied for cultivars of sour orange (seedless, sweet seeded, Brazilian and Spanish), common sweet orange (Florida, Fsido, Shamoty, and Valencia) and navel orange B29 from four different areas in Egypt (El-Qalubaiya governorate, Wadi El-Mollak; Ismailia governorate, El-Salheia; Sharqaia governorate, and El-Minya; South Egypt). Cluster analysis generated by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) molecular marker showed close similarities of the four sour orange accessions, used as rootstocks, where they were grouped in one cluster. The four cultivars of sweet common orange and sweet navel orange was linked together in a separate cluster. Navel orange cultivated at El-Minya and El-Salheia showed drop in yield due to substantial flower and young fruit abscission, whereas trees of the same cultivar did not suffer from abscission and yielded enhanced crop. Comparison of the four previously mentioned localities speculated that the navel orange accessions at El-Minya and El-Salheia are subjected to drought stress. This could be further verified by the substantially enhanced levels of abscisic acid in the plants showing abscission, as compared to those exhibiting normal flowering and enhanced fruiting at El-Qalubaiya and Wadi El- Mollak.