The Labour Market in Cognitive Bio-Capitalism. the Italian Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Information Education and Training Professional Experience

CURRICULUM VITAE Personal information Family name : Kiikeri First name : Markku Nationality : Finnish Date of birth : 1.9.1964 Gender : Male Professional address : Telephone number : +358-(0)54-4844010 (Fin), +32474924612 (Bel) Fax : E-mail : [email protected], [email protected] [email protected] Education and training Institution (Date) Degree(s) or Diploma(s) obtained 2005-2009, University of Helsinki University pedagogy I-III, 50 university credits (final thesis not completed) 1999, European University Institute, Florence, Italy Doctor of Law, dr.iur. 1992, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, Belgium Master of International and Comparative Law, LLM 1991, University of Turku, Finland Master of Law, LLM 1990, Institute of Human Rights, Äbo Akademi, Certificate Turku, Finland 1989, Hague Institute for International Law Certificate Professional experience Date from – Location Employer Position Description Date to 2015 UNAM/Mexico city Lecturer European law 2014/2015 La Salle university/Mexico Lecturer European law, human city rights 2013 Universite de Montpellier/ Lecturer European law, Basics of France, Faculty of Law, Law Tallinn University/Estonia, Faculty of Law 2012 Universita degli Studi, Lecturer European law, Legal Milan/Italy, Faculty of theory Political and social sciences, Tallinn University/Estonia, Faculty of Law 2011 Vytautas Magnus Lecturer European law, visiting University/Kaunas, Faculty professor of Law, University of Oulu/Technology 2009-2010 Dundee Business Lecturer, teacher Visiting lecturer, School/UK, University -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Personal information Family name: Kiikeri First name: Markku Nationality: Finnish Date of birth: 1.9.1964 Gender : Male Professional address: Kiertotie 53, 96100 Rovaniemi, Finland Telephone number: +358-(0)40-4844010, +358-(0)50-9117919 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Education and training Institution (Date) Degree(s) or Diploma(s) obtained 2005-2009, University of Helsinki University pedagogy I-III, 50 university credits (final thesis not completed) 1999, European University Institute, Florence, Italy Doctor of Law, dr.iur. (Academy of Finland) 1992, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, Belgium Master of International and Comparative Law, LLM 1991, University of Turku, Finland Master of Law, LLM 1990, Institute of Human Rights, Äbo Akademi, Certificate Turku, Finland 1989, Hague Institute for International Law Certificate Professional experience Date from – Location Employer Position Description Date to 2020 Sami Parliament, Finland Sami Attorney, rapporteur Appeals to the Supreme autumn parliament court 2020 Spring Helsinki University of Professor/Lecturer Teaching United London Kingdom Public law, 44 hours 2008- University of Lapland, Assistant professor Lecturer, research, Rovaniemi/Finland in European law an, administration, member philosophy of law of pedagogical planning and social sciences board, etc. 2006- University of Turku and Adjunct professor European law University of Lapland (Title of Docent) 1.1.2019- Sami Parliament, Finland Sami Attorney, rapporteur Appeals to the Supreme 31.2.2020 -

M O R in I Competition Ar M Sa

ETIT MP IO O N C A I THE INVENTOR OF R N COMPRESSED AIR PISTOLS M I DER ERFINDER R S DER PRESSLUFTPISTOLE O A M SWISS MADE ETIT THE INVENTOR DER ERFINDER MP IO O N C A I OF COMPRESSED DER PRESSLUFT- R N M I R S AIR PISTOLS PISTOLE O A What is now produced by all big Was heute von allen grossen M pistol manufacturers and every year Pistolenherstellern produziert more used by the best shooters und immer mehr von den besten comes from a project presented Schützen weltweit verwendet wird, for the first time worldwide in stammt von einem Projekt, welches 1992 by Morini Competition Arm zum ersten Mal im Jahr 1992 S.A., the CM 162E. The use of von Morini Competition Arm SA compressed air, electronic trigger präsentiert wurde: die CM 162E, and ball bearing trigger unit. The welche Pressluft verwendet und excellent results shown at Olympic eine elektronisch kugelgelagerte Games, World Championships, Abzugseinheit hat. Die hervorragenden World Cups, European and National Ergebnisse bei Olympischen Spielen, Championships are a proof of good Weltmeisterschaften, Weltcups, project and good gun. One of the europäischen und nationalen world’s legendary shooters, Ragnar Meisterschaften sind Beweis dafür, Skanaker from Sweden actively took dass es sich um ein gutes Produkt part in the design. The cooperation handelt. Der weltbekannte legendäre with the great Skanaker also brought Schütze, Ragnar Skanaker aus further fruits and, in 1993, the Schweden, nahm aktiv an der CM 84E free pistol was born, sporting Projektentwicklung teil. an electronic trigger, ball bearing and Die Zusammenarbeit mit dem a sensor which detects the finger’s „grossen Skanaker“ brachte weitere presence inside the trigger guard. -

01 EU – Croatia

EU Bibliography Compiled by: Aleksandra Čar, European Law Information Centre, Faculty of Law, Zagreb Below you will find a list of bibliographic references to selected articles in the field of European law and policy. This issue covers items from a wide range of academic and specialised periodicals published from December 2011 to October 2012. References are presented in 19 subject headings covering all activities of the European Union. 01 EU – Croatia 1 ĆUDINA, Andrijana; Lukini ć, Gordana; Suši ć, Gordi. Croatia's Export Performance in the EU Market . Ekonomski pregled . 63 (2012) No. 5-6: 291. 2 DŽIHI Ć, Vedran; Segert, Dieter; Wieser, Angela. The Crisis of Representative Democracy in the Post-Yugoslav Region: Discrepancies of Elite Policies and Citizens' Expectations . Southeastern Europe . 36 (2012) No. 1: 87. 3 FABIJANI Ć GAGRO, S.; Vukas, B. Jr. The Path of the Former Yugoslav Countries to the European Union: From Integration to Disintegration and Back . Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law . 19 (2012) No. 2: 300. 4 GOLDNER LANG, Iris. The Impact of Enlargement(s) on the EU Institutions and Decision- Making: special focus: Croatia . Yearbook of European Law . 31 (2012): 1. 5 GREGOVI Ć, Marko. A Human Rights Based Evaluation of the Croatian Asylum System in the Context of Europeanization . Croatian Yearbook of European Law and Policy . (2011) No. 7: 135. 6 HORVAT, Sre ćko; Štiks, Igor. Post-Socialism, the European Union, and a New Left in the Balkans . Monthly Review . 63 (2012) No. 10 7 PECOTI Ć KAUFMAN, Jasminka. Croatia: Abuse of Dominant Position – Cigarettes . ECLR – European Competition Law Review . -

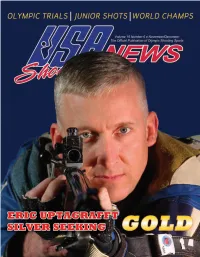

USAS Nov Dec5ver6 Small.Pdf

USA SHOOTING 1 Olympic Plaza Colorado Springs, CO 80909 Phone: 719-866-4670 Columns Administration Fax: 719-866-2200 Competitions Fax: 719-866-4884 6 From the Director Calling all USAST Members USAS STAFF USA’s Kim Rhode is all smiles after her first ISSF Chief Executive Officer: Robert Mitchell 8 Coaches’ Corner [email protected], ext. 4899 World Cup Final gold medal in Women’s Skeet. Planning for Your Match Executive Director of USAST Foundation: Buddy DuVall 8 Technical [email protected], 719-866-4880 Trigger Release Part I Chief Development Officer: Tom Harris Photo ISSF [email protected] 22 AIM with the AMU Director, Marketing & Communications: Corrie West Uptagrafft: Silver Seeking Gold Let’s Make Good . Great! [email protected], ext. 4616 Eric Uptagrafft has seen a lot of silver in the past Competitions Director: Nicole Levine 26 Training [email protected], ext. 4885 two years, but this time he’s aiming for gold. Are you Fundamentally Sound? Competitions Coordinator: Pete Carson 28 Equipment [email protected], ext. 4897 What is the Best Airgun? National Paralympic Coach: Bob Foth 2011 NJOSC for Shotgun [email protected], ext. 4881 30 Athlete of the Month National Pistol Coach: Sergey Luzov Junior talent shined at the 2011 National Junior Glenn Eller [email protected], ext. 4615 Olympic Championships for Shotgun in Colorado. National Rifle Coach: Dave Johnson 31 Youth Programs [email protected], ext. 4630 The 2011 PPP National Champs National Shotgun Coach: Bret Erickson [email protected] Media & PR Manager: Katie Yergensen Sponsors, Suppliers & Supporting Partners [email protected], ext. -

Game Notes Vs. Finland • Thursday, May 18, 2017 • 2017 IIHF Men’S World Championship • Page Two

Team USA Game Notes 2017 IIHF Men’s World Championship • Cologne, Germany USA (6-0-0-1) vs. Finland (2-2-1-2) Thursday, May 18, 2017 • LANXESS Arena • Quarterfinals Team USA Schedule (times are local/ET) USA Hockey Media Officer: Dave Fischer Email: [email protected] • Cell: +447771830718 Friday, May 5 -- Group A (Cologne) USA vs. Germany* L, 1-2 • TODAY’S GAME The U.S. Men’s National Team faces Finland today Sunday, May 7 -- Group A (Cologne) (live on NBCSN in U.S.) in the quarterfinal round of the USA vs. Denmark* W, 7-2 2017 International Ice Hockey Federation Men’s World Monday, May 8 -- Group A (Cologne) Championship at LANXESS Arena in Cologne, Germany. USA vs. Sweden* W, 4-3 The winner advances to play either Sweden or Switzerland in Wednesday, May 10 -- Group A (Cologne) the semifinals on Saturday, while the loser goes home. USA vs. Italy^ W, 3-0 Saturday, May 13 -- Group A (Cologne) • JIMMY HOWARD GETS NOD IN GOAL TODAY Latvia vs. USA* W, 5-3 Jimmy Howard will start in goal today against Finland. In Howard’s other appearance in the men’s worlds (2012), Sunday, May 14 -- Group A (Cologne) he faced Finland twice. In the preliminary round, Howard Slovakia vs. USA* W, 6-1 recorded an 18-save shutout in a 5-0 win. In the quarterfinals Tuesday, May 16 -- Group A (Cologne) that year, he made 28 saves in a 3-2 loss. Finland’s Jesse Russia vs. USA^ W, 5-3 Joenssu scored with :09 left in regulation to secure the victo- Thursday, May 18 -- Quarterfinals (TBD) ry. -

Gamifin Conference 2020

GamiFIN Conference 2020 Proceedings of the 4th International GamiFIN Conference Levi, Finland, April 1-3, 2020 (Organized as an online conference) Edited by Jonna Koivisto Gamification Group, Tampere University, Finland Mila Bujić Gamification Group, Tampere University, Finland Juho Hamari Gamification Group, Tampere University, Finland GamiFIN 2020 Proceedings This volume of CEUR-WS Proceedings contains 20 papers presented at the 4th International GamiFIN Conference (GamiFIN 2020). The conference was held as an online conference on April 1-3, 2020. Copyright © 2020 for the individual papers by the papers’ authors. Copying permitted only for private and academic purposes. This volume is published and copyrighted by its editors. Preface The GamiFIN conference is an annual international academic conference on gamification with rigorous double blind international peer-review practices. The conference brings together a community of researchers and practitioners to present results from their latest work regarding gamification. The fourth international GamiFIN conference, organized by the Gamification Group, took place on April 1-3, 2020. The conference was planned to be held in Levi, Finland, but due to the COVID- 19 pandemic restrictions the conference was held online. All of the planned conference sessions and keynote were delivered and attended by the conference participants using Zoom software. GamiFIN 2020 was chaired by Professor Juho Hamari and Dr. Jonna Koivisto. GamiFIN 2020 conference was proud to have as a keynote speaker Assistant Professor Andreas Lieberoth (University of Aarhus, Denmark) who has conducted extensive research on the behavioural and psychological impact of gamification. GamiFIN 2020 included six academic paper sessions: 1) Gamification (general); 2) Gamification & Education; 3) Gamification & Consumption; 4) Gamification on the Move; 5) Gameful Media; and 6) Esports and Streaming. -

EDISON CYLINDERS Blue Amberols Are Housed in Fine Quality Reproduction Edison Orange Boxes Or in Original Boxes

EDISON CYLINDERS Blue Amberols are housed in fine quality reproduction Edison orange boxes or in original boxes. Wax cylinders are in padded boxes, either original or appropriately protective. Any mold on wax cylinders is always described. All grading is visual and refers to the cylinders rather than the boxes. 4354. 2-M 17139. CÉCILLE MERGUILLIER [s]. DOMINO NOIR: Un fée (Auber). Just about 1-2. $40.00. 4355. 2-M 15897. FRANZISKA KRUG-ELFGEN [s]. SCHLARAFFENDLAND: Walzerlied (Schleif- fahrt). Just about 1-2. $40.00. 4356. 2-M 18070. PIERRE CORNUBERT [t]. LA DAME BLANCHE: Ah! quel plaisir d’être soldat (Boieldieu). Just about 1-2. $75.00. 4353. 4-M Wax Amberol B-152. LEO SLEZAK [t] STÄNDCHEN (Schubert). Just about 1-2. $75.00. 4351. 4-M Wax Amberol B-165. FLORENCIO CONSTANTINO [t]. TOSCA: Recondita armonia (Puccini). Just about 1-2. $75.00. 4348. 4-M Wax Amberol B-166. BLANCHE ARRAL [s]. MIGNON: Polonaise (Thomas). Just about 1-2. $40.00. 4350. 4-M Wax Amberol B-174. ADELINA AGOSTINELLI [s], ATTILIO PAROLA [t]. LA BOHÈME: O soave fanciulla (Puccini). Just about 1-2. $75.00. 4349. 4-M Wax Amberol 30044. MARIE RAPPOLD [s]. CHANSON PROVENÇALE (Dell’Acqua) Just about 1-2. $40.00. 4352. 4-M Wax Amberol 844. HENRI SCOTT [bs]. O’ER THE FRESH GREEN FIELDS (Chami- nade). Just about 1-2. $20.00. 4363. 4-M Blue Amberol 2388. CLEMENTINE DE VERE SAPIO [s], VERNON ARCHIBALD [b]. ROSE OF THE MOUNTAIN TRAIL (Brennan). Archibald sings the main tune about Rose, who we hear vocalizing in the distance on the Mountain Trail. -

Swiss Made the Inventor of Compressed Air Pistol Der Erfinder Der Pressluftpistole

THE INVENTOR OF COMPRESSED AIR PISTOL DER ERFINDER DER PRESSLUFTPISTOLE SWISS MADE ETIT MP IO O N C A I R N M I R S O A M Morini Competition Arm S.A. Via ai gelsi, 11 CH-6930 Bedano - Switzerland tel.: +41 91 935 22 30 fax.: +41 91 935 22 31 [email protected] www.morini.ch THE INVENTOR DER ERFINDER OF COMPRESSED DER PRESSLUFT- AIR PISTOL PISTOLE What is now produced by all Was heute von sämtlichen pistol manufacturers and used Pistolenherstellern produziert by more and more increasing und von den besten Schützen number of shooters, is the weltweit verwendet wird, result of a successfull project stammt aus einem Projekt, presented worldwide the das erstmals 1992 von Morini first time in 1992 by Morini Competition Arm SA weltweit Competition Arm SA: the vorgestellt wurde: die CM 162E compressed air pistol CM 162E. mit Pressluftsystem. Dieses The modell uses exclusively Modell löst die CO2 Pistolen compressed air, has an vollständig ab und verwendet electronic trigger und ball ausschliesslich Pressluft bearing trigger unit system. und hat eine elektronisch The excellent results shown kugelgelagerte Abzugseinheit. at Olympic Games, World Die hervorragenden Ergebnisse Championships, World Cups, bei Olympischen Spielen, European and National Weltmeisterschaften, Weltcups, Championships are the proof europäischen und nationalen of a good project and a good Meisterschaften sind Beweis product. One of the world’s dafür, dass es sich um ein legendary shooter Ragnar bewährtes Produkt handelt. Skanaker from Sweden, actively Der weltbekannte legendäre took part in the project. The Schütze, Ragnar Skanaker aus cooperation with Skanaker also Schweden, nahm aktiv an der brought further fruits and, Projektentwicklung teil. -

Registration Status IWA Outdoorclassics 2022 As of 28.06.2021

Registration status IWA OutdoorClassics 2022 as of 28.06.2021 Among others, the following companies have already signed up for IWA OutdoorClassics 2022. We expect many more registrations in the coming weeks. 5.11 Sweden 3E Electro Optical Systems Turkey 3HGR Slings Finland 4 stable stick France 4-14 Factory Italy 4MILITARY Sp. z o.o. - RUBOX system Poland 4SYS FOOTWEAR Netherlands Abílio P. Carneiro & Filhos S.A Portugal ABRONA International Pakistan ACCURIZE AS Norway ACETECH Taiwan ACI Laser GmbH Germany ACMA - Distributor For Fine Knives Germany ACT-MAG SRL Italy ADC Armi Dallera Custom srl Italy ADLER ARMS Turkey AGAOGLU / AHSS Turkey AGM Global Vision Ltd U S A Aguila Ammunition U S A AGUIRRE Y ARANZABAL Spain ahg-Anschütz Handels GmbH Germany Aimpoint AB Sweden aimSport Sweden AB Sweden Air Chrony s.r.o. Czech Republic Airgun Technology Czech Republic Airsoft Innovations Inc. Canada AK SAVUNMA Turkey AKAH Albrecht Kind GmbH Germany Akar Holster Turkey Akdas Arms Company Turkey AKKAR Turkey Alan Paine Country Collection United Kingdom Albrecht Bender GmbH u. Co Germany ALFAPROJ spol. s r.o. Czech Republic Allen Company U S A Alpenheat GmbH Austria Alpha Loading Systems U S A Alpha Optics Canada ALSACE LIMITED China ALTEK DOKUM AS Turkey Amazing Industries Pakistan 1 Registration status IWA OutdoorClassics 2022 as of 28.06.2021 American Outdoor Brands U S A AMMUNITIONS EG DEL SUR Spain ANATOLIA Fisek A.S. Turkey Andres Industries AG Germany ANORAK HELLAS LTD Greece ANSCHÜTZ GmbH & Co. KG Germany Antonini srl Italy ANTREG Czech Republic ANV Knives Czech Republic APOLO AIRGUNS Argentina APS Limited Hong Kong ARDESA Spain AREX defense Slovenia Arktis United Kingdom ARMA ZEKA Czech Republic Armanov Slovenia Armed Guns Turkey Armi Perazzi SpA Italy ArmourLite Watch Company U S A Armsan Turkey ARMSCOR Global Defense, Inc. -

Greece: with an Ai to the Future

GREECE: WITH AN AI TO THE FUTURE in collaboration with 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 6 2. AI Explained 9 2.1 Introduction 10 2.2 So, what is exactly Artificial Intelligence? 12 2.3 Conclusion 17 3. The Greek AI Public Sentiment 19 3.1 Introduction 20 3.2 AI enters the public’s consciousness 20 3.3 Prospects of an AI future - For better or for worse? 21 3.4 AI trust for selected tasks 26 3.5 Conclusion 29 4. Greek Organizations’ AI Readiness 31 4.1 Introduction 32 4.2 AI as an ″agent for change″ 33 4.3 Greek organizations’ AI inertia 37 4.4 Responsible AI - With great power comes great responsibility 41 4.5 Conclusion 45 5. AI as a driver for Greece’s Growth 47 5.1 Introduction 48 5.2 Factoring in AI to boost the national economic growth 49 5.3 Dissecting the additional GDP growth 50 5.4 Seizing AI’s full potential - The National Absorptive Capacity Index 55 5.5 Conclusion 61 6. Next Steps for Policy Makers and Business Leaders 63 6.1 Introduction 64 6.2 For Policy Makers: Clearing the path to an AI future 65 6.3 For Business Leaders: Creating a new playbook for an AI world 74 6.4 Conclusion 81 Appendix: Study Notes 82 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Copyright © 2019 Accenture. All rights reserved. FOREWORD Artificial Intelligence (AI) transforms our societies, The potential is enormous. Our world is becoming the way we perceive the world, essentially altering more intelligent. -

Public Sector Economics Program

CONFERENCE PUBLIC SECTOR ECONOMICS OCTOBER 14-15, 2016, ZAGREB, CROATIA PROGRAM DAY 1 (OCTOBER 14, 2016) 8.30―9.00 REGISTRATION OPENING KATARINA OTT, Institute of Public Finance MAX BRÄNDLE, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung 9.00―10.00 ZRINKA ŽIVKOVIĆ MATIJEVIĆ, Raiffeisenbank Austria d.d. MANICA HAUPTMAN, European Commission Representation in the Republic of Croatia ZDRAVKO MARIĆ, Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Croatia KEYNOTE SPEECH 10.00―10.45 EHTISHAM AHMAD, Center for Development Research, University of Bonn and London School of Economics and Political Science 10.45―11.00 Break PLENARY SESSION 11.00―12.15 Session 1: Macro fiscal policy issues 12.15―12.30 Break PARALLEL SESSIONS 12.30―13.45 Session 2: Taxation 1 Session 3: Local public finance and transparency 13.45―14.45 Lunch KEYNOTE SPEECH 14.45―15:30 MATTHIAS KOLLATZ-AHNEN, Bundesrat, Berlin, Senator for Finance 15.30―15.45 Break PARALLEL SESSIONS 15.45―17.00 Session 4: Macroeconomy and sustainability Session 5: Sport, culture and infrastructure 1 PUBLIC SECTOR ECONOMICS: PROGRAM DAY 2 (OCTOBER 15, 2016) PARALLEL SESSIONS 9.00―10.15 Session 6: Social protection and education Session 7: Capital flows and fiscal policy 10.15―10.30 Break PARALLEL SESSIONS 10.30―11.20 Session 8: Empirics of current fiscal issues Session 9: Institutions and governance 11.20―11.30 Break PLENARY SESSION 11.30―12.45 Session 10: Taxation 2 KEYNOTE SPEECH 12.45―13.30 DEBORA REVOLTELLA, European Investment Bank 13.30―13.45 CONCLUDING REMARKS 13.45―14.30 Lunch PROGRAM COMMITTEE DUBRAVKO MIHALJEK, Bank for