Texas Advance Directives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cool Canadian Crime 2021

2021 Second Edition Cool Canadian Crime 2021 Books by Release Month January Carolyn Arnold, The Little Grave, Bookouture Vicki Delany, A Curious Incident, Crooked Lane Books A.J. Fotheringham, Secrets at the Spa, Book 4 of The Lamb's Bay Mysteries, Amazon Sarah Fox, A Room with a Roux (A Pancake House Mystery #7), Kensington Lyrical Barbara Fradkin, The Ancient Dead, Dundurn Press Jim Koris, Human Trafficking, the Retribution, Austin Macauley Publishers USA Lorna Poplak, The Don: The Story of Toronto's Infamous Jail, Dundurn Byron TD Smith, Windfall: A Henry Lysyk Mystery, Shima Kun Press Alan R Warren, Zodiac Killer Interviews, House of Mystery February Alice Bienia, Knight Trials, A. Bienia Victoria Hamilton, Double or Muffin, Beyond the Page Publishing Wendy Heuvel, Faith, Rope, and Love - Faith and Foils Cozy Mystery Series #4, Olde Crow Publishing Robert Rotenberg, Downfall, Simon & Schuster Alan R Warren, JFK Assassination: The Interviews, House of Mystery Alan R Warren, Jack the Ripper : The Interviews, House of Mystery March Diane Bator, All That Shines, BWL Publishing Ltd. Richard Boyer, Murder 101, Friesen Press William Deverell, Stung, ECW Press RM Greenaway, Five Ways to Disappear, Dundurn Press Julie Hiner, Acid Track, KillersAndDemons.com John MacGougan, Secrets of the Innocent, Tellwell Talent C.S. O'Cinneide, Starr Sign: The Candace Starr Series, Dundurn Press Gloria Pearson-Vasey, The Hallowmas Train, Tellwell Talent Judy Penz Sheluk, Where There's A Will, ACX/Judy Penz Sheluk Chris Racknor, Hidden Variables, Yellow Brick -

![[S6X4]⋙ Safe Harbour by Danielle Steel #1JVZ2RIS8CQ #Free Read](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4361/s6x4-safe-harbour-by-danielle-steel-1jvz2ris8cq-free-read-3164361.webp)

[S6X4]⋙ Safe Harbour by Danielle Steel #1JVZ2RIS8CQ #Free Read

Safe Harbour Danielle Steel Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically Safe Harbour Danielle Steel Safe Harbour Danielle Steel In her fifty-ninth bestselling novel, Danielle Steel tells an unforgettable story of survival...of how two people who lost everything find hope...and of the extraordinary acts of faith and courage that bring —and keep— families together... On a windswept summer day, as the fog rolls across the San Francisco coastline, a solitary figure walks down the beach, a dog at her side. At eleven, Pip Mackenzie's young life has already been touched by tragedy; nine months before, a terrible accident plunged her mother into inconsolable grief. But on this chilly July afternoon, Pip meets someone who fills her sad gray world with color and light. And in her innocence and in his kindness, a spark will be kindled, lives will be changed, and a journey of hope will begin. From the moment the curly-haired girl walks up to his easel on the sand, Matt Bowles senses something magical about her. Pip reminds him of his own daughter at that age, before a bitter divorce tore his family apart and swept his children halfway across the world. With her own mother, Ophélie, retreating deeper into her grief, Pip spends her summer at the shore the way lonely children do: watching the glittering waters and rushing clouds, daydreaming and remembering how things used to be. That is, until she meets artist Matt Bowles, who offers to teach the girl to draw—and can't help but notice her beautiful, lonely mother. -

Halifax Explosion Diary of Charlotte Blackburn

Reference List 1. Lawson, Julie. NO SAFE HARBOUR: THE HALIFAX EXPLOSION DIARY OF CHARLOTTE BLACKBURN. Scholastic Canada Ltd.; 2006; ISBN: 0-439-96930-1. Keywords: Explosion; Marine Calamities; Fatalities; Children's Reactions Call Number: JUV.130.L3.N6 Notes: Gift of T. Joseph Scanlon Family Series title: Dear Canada 2. Verstraete, Larry. AT THE EDGE: DARING ACTS IN DESPERATE TIMES. New York: Scholastic; 2009; ISBN: 978-0-545-27335-0. Keywords: Explosion; Chemical Disaster; Tsunamis-Case Studies; Hurricanes-Case Studies; Floods-Case Studies; Terrorism Call Number: JUV.135.V4.A8 (ELQ RC Annex) Notes: Contents: At the Edge of Disaster At the Edge of Terror At the Edge of Injustice At the Edge of the Impossible Abstract: More than twenty incredible true stories show people facing critical life-or-death choices, and the decisions that had to be made, at the edge... Includes sections about the Halifax explosion of 1917, the Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster, the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, Hurricane Katrina and the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 3. Kitz, Janet F. SURVIVORS: CHILDREN OF THE HALIFAX EXPLOSION. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Nimbus Publishing Ltd; 1992; ISBN: 1-55109-034-1. Keywords: Explosion; Children's Reactions; Caring for Survivors Call Number: JUV.150.K5.S8 (ELQ RC Annex) Notes: Both copies gifts of T. Joseph Scanlon Family Library owns 2 copies. Contents: December, 1917 Life in Richmond Morning, December 6, 1917 Explosion! Refuge What Next? A New Life Begins Back to School A Different Kind of School Looking Back Abstract: Over five hundred children from Halifax and Dartmouth were killed when the munitions ship Mont Blanc, blew up in the city's harbour on December 6, 1917. -

A Chronology of Danielle Steel Novels the NUMBERS GAME March 2020 Hardcover (9780399179563) MORAL COMPASS January 2020 Hardcov

A Chronology of Danielle Steel Novels THE NUMBERS GAME March 2020 Hardcover (9780399179563) MORAL COMPASS January 2020 Hardcover (9780399179532) SPY November 2019 Hardcover (9780399179440) CHILD’S PLAY October 2019 Hardcover (9780399179501) THE DARK SIDE August 2019 Hardcover (9780399179419) LOST AND FOUND June 2019 Hardcover (9780399179471) March 2020 Paperback (9780399179495) BLESSING IN DISGUISE May 2019 Hardcover (9780399179327) January 2020 Paperback (9780399179341) SILENT NIGHT March 2019 Hardcover (9780399179389) December 2020 Paperback (9780399179402) TURNING POINT January 2019 Hardcover (9780399179358) July 2019 Paperback (9780399179372) BEAUCHAMP HALL November 2018 Hardcover (9780399179297) October 2019 Paperback (9780399179310) IN HIS FATHER’S FOOTSTEPS September 2018 Hardcover (9780399179266) May 2019 Paperback (9780399179280) THE GOOD FIGHT July 2018 Hardcover (9781101884126) March 2019 Paperback (9781101884140) THE CAST May 2018 Hardcover (9781101884034) January 2019 Paperback (9781101884058) ACCIDENTAL HEROES March 2018 Hardcover (9781101884096) December 2018 Paperback (9781101884119) FALL FROM GRACE January 2018 Hardcover (9781101884003) October 2018 Paperback (9781101884027) PAST PERFECT November 2017 Hardcover (9781101883976) August 2018 Paperback (9781101883990) FAIRYTALE October 2017 Hardcover (9781101884065) May 2018 Paperback (9781101884089) THE RIGHT TIME August 2017 Hardcover (9781101883945) April 2018 Paperback (9781101883969) THE DUCHESS June 2017 Hardcover (9780345531087) February 2018 Paperback (9780425285411) -

Penticton Reads Ballots Results Bad - Good 1 - 5 Title Author Rating Comments Brava Valentine a Trigiani 3 the Woman in the Window A

Penticton Reads Ballots Results Bad - Good 1 - 5 Title Author Rating Comments Brava Valentine A Trigiani 3 The Woman in the Window A. J. Finn 4 First rate mystery/thriller! lots of parts to skip through as writing repetitive and darkness before dawn ace collins 2 unnecessary The Great Nadar Adam Begley 4 Intersting man, colourful and talented Kiss Carlo Adriana Trigiani 4 An intriguing storyline. Started re-reading. Intense and emotional story. Very different women come together in a "Mommy" group to share their experience and support each other as they navigate life being first-time mothers with newborn babies. Tragedy draws them closer but no one is prepared when secrets are revealed. Lots of twists The Perfect Mother: A Novel Aimee Molloy 4 and turns before a surprising ending. Truth Al Franken 4 If you were here Alafair Burke 5 Things I Overheard While … Alan Alda 5 Turned into an amusing writer Excellent very detailed but easy to read about early history of A savage empire alan axelrod 5 North America A book from my book shelf about reirement and how to Advance to go Alan Dickson 3 prepare, over simplistic and not realistic in 2018! Murder Most Malicious Alyssa Maxwell 4 BREATH OF FIRE AMANDA BOUCHET 5 LOTS OF ACTION AND ROMANCE lethal licorice amanda flower 5 Death's daughter Amber Benson 5 lots of action A gentleman in Moscow Amor Towle 5 Interesting, sad and funny. Enjoyable the rift frequency amy foster 3 Not a fast read, but extremely interesting.Every human emotion The Valley of Amazement Amy Tan 5 is in this book. -

Safe Harbour Oral Evidence and Written Submissions

EUROPEAN UNION COMMITTEE HOME AFFAIRS, HEALTH AND EDUCATION SUB- COMMITTEE Safe Harbour Oral Evidence and Written Submissions Contents Caspar Bowden, Phil Lee and Professor Charles Raab—Oral Evidence (QQ1-11) .................... 2 European Commission—Oral Evidence (QQ12-20) ....................................................................... 40 European Data Protection Supervisor and Information Commissioner’s Office—Oral Evidence (QQ21-32) ............................................................................................................................... 58 Information Commissioner’s Office—Written Evidence ................................................................ 82 Information Commissioner’s Office and European Data Protection Supervisor—Oral evidence (QQ21-32) ............................................................................................................................... 86 Information Commissioner’s Office—Supplementary Written Evidence ................................... 87 Phil Lee, Caspar Bowden and Professor Charles Raab—Oral Evidence (QQ1-11) ................. 89 Professor Charles Raab, Caspar Bowden and Phil Lee—Oral Evidence (QQ1-11) ................. 90 UK Government—Oral evidence (QQ33-46) .................................................................................. 91 Caspar Bowden, Phil Lee and Professor Charles Raab—Oral Evidence (QQ1-11) Caspar Bowden, Phil Lee and Professor Charles Raab—Oral Evidence (QQ1-11) Evidence Session No. 1 Heard in Public Questions 1 - 11 WEDNESDAY -

The Hotel Riviera by Elizabeth Adler the House in Amalfi by Elizabeth

Romance and Suspense Romance: The Hotel Riviera by Elizabeth Adler I am traveling abroad with Elizabeth Adler this summer. Great light read for the summer. The House in Amalfi by Elizabeth Adler Pleasure to read. Good author, great descriptions. You experience the location, even the food. Invitation to Provence by Elizabeth Adler I always enjoy Ms. Adler’s books. They are romantic, light reading with a little mystery. Heart of a Husband by Kathryn Alexander This is a love inspired book not a Harlequin Romance. No sex. Just a good romance. I enjoyed reading it. My Sunshine by Catherine Anderson Loved the book. I will read other books by this author. I Took My Love to the Country by Margaret Culkin Banning O.K. I would not recommend it. Every Move She Makes by Beverly Barton I did not enjoy this book. For me, it started off bad and kept going. I probably wouldn’t read any other books by this author. Just Rewards by Barbara Taylor Bradford This is the story of Linnet O’Neil. The family has owned a store or rather a series of stores called Hartes. It is also a family saga going back to her Great-Grandmother. Very interesting story. Flashpoint by Susanne Brookmann Fast paced action from page 1. Interestingly developed characters. Plots and subplots catching – great read, can’t put it down. The Fifth Daughter by Elaine Coffman I can see and feel how the fifth daughter feels because I was a middle child and dealt with some of the same things even though I was not a fifth daughter. -

Danielle Steel's

Danielle Steel Danielle Steel Danielle Steel Partial Checklist Partial Checklist Partial Checklist (1996-2013) (1996-2013) (1996-2013) Winners (Oct.. 2013) The House Winners (Oct.. 2013) The House Winners (Oct.. 2013) The House Until the End of Time Impossible Until the End of Time Impossible Until the End of Time Impossible First Sight Miracle First Sight Miracle First Sight Miracle Sins of the Mother Toxic Bachelors Sins of the Mother Toxic Bachelors Sins of the Mother Toxic Bachelors Friends Forever Echoes Friends Forever Echoes Friends Forever Echoes Betrayal Ransom Betrayal Ransom Betrayal Ransom Hotel Vendome Second Chance Hotel Vendome Second Chance Hotel Vendome Second Chance Happy Birthday Dating Game Happy Birthday Dating Game Happy Birthday Dating Game 44 Charles Street Johnny Angel 44 Charles Street Johnny Angel 44 Charles Street Johnny Angel Legacy Safe Harbour Legacy Safe Harbour Legacy Safe Harbour Family Ties Answered Prayers Family Ties Answered Prayers Family Ties Answered Prayers Big Girl The Cottage Big Girl The Cottage Big Girl The Cottage Southern Lights Sunset in St. Tropez Southern Lights Sunset in St. Tropez Southern Lights Sunset in St. Tropez Matters of the Heart The Kiss Matters of the Heart The Kiss Matters of the Heart The Kiss One Day at a Time Leap of Faith One Day at a Time Leap of Faith One Day at a Time Leap of Faith A Good Woman Lone Eagle A Good Woman Lone Eagle A Good Woman Lone Eagle Honor Thyself The House on Hope Honor Thyself The House on Hope Honor Thyself The House on Hope Street Street Street Rogue Rogue Rogue Journey Journey Journey Amazing Grace Amazing Grace Amazing Grace The Wedding The Wedding The Wedding Bungalow 2 Bungalow 2 Bungalow 2 Bittersweet Bittersweet Bittersweet Sisters Sisters Sisters Granny Dan Granny Dan Granny Dan Coming Out Coming Out Coming Out Irresistible (1996) Irresistible (1996) Irresistible (1996) H. -

Taltp-Spring-2008-American-Romance

Teaching American Literature: A Journal of Theory and Practice Special Issue Spring/Summer 2008 Volume 2 Issue 2/3 Suzanne Brockmann (Anne Brock) (5 June 1960- Suzanne Brockmann, New York Times best-selling and RITA-award-winning author, pioneered and popularized military romances. Her well-researched, tightly-plotted, highly emotional, action-packed novels with their socially- and politically-pertinent messages have firmly entrenched the romance genre in the previously male-dominated world of the military thriller and expanded the reach and relevance of the romance genre far beyond its stereotypical boundaries. The Navy SEAL heroes of her Tall, Dark and Dangerous series published under the Silhouette Intimate Moments imprint and the heroes and even occasionally the heroines of her best-selling, mainstream Troubleshooter series who work for various military and counter-terrorism agencies have set the standards for military characters in the romance genre. In these two series, Brockmann combines romance, action, adventure, and mystery with frank, realistic examinations of contemporary issues such as terrorism, sexism, racial profiling, interracial relationships, divorce, rape, and homosexuality. Brockmann’s strong, emotional, and realistic heroes, her prolonged story arcs in which the heroes and heroines of future books are not only introduced but start their relationships with each other books before their own, and her innovative interactions with her readers, have made her a reader favorite. Suzanne was born in Englewood, New Jersey on 6 May, 1960 to Frederick J. Brockmann, a teacher and public education administrator, and Elise-Marie “Lee” Schriever Brockmann, an English teacher. Suzanne and her family, including one older sister, Carolee, born 28 January, 1958, lived in Pearl River, N.Y., Guilford, Conn., and Farmingdale, N.Y., following Fred Brockmann’s career as a Superintendent of Schools. -

1 BOOK REVIEW of LEAP of FAITH by DANIELLE STEEL Yessi

BOOK REVIEW OF LEAP OF FAITH BY DANIELLE STEEL Yessi Tifa Nuraina (13020111150012) : Jurusan Strata 1 Sastra Inggris Universitas Diponegoro Semarang Abstract Leap of Faith is a novel by a famous novelist Danielle Steel. Leap of Faith debuted at the New York Times and is listed as the best-selling novel to fifty-two of Danielle Steel. This novel is about a girl from France, she is Marie-Ange Hawkins who lives in a magnificent castle name, Chateau de Marmouton. At the castle, she has childhood like everyone's dream. She has the freedom, security and abundant affection of both parents and her brother. But when Marie-Ange Hawkins is eleven years old, a tragic accident that befell his parents take her happiness. She becomes an orphan and is sent to America to live with a cruel aunt of her father. Alone in a foreign land, Marie-Ange Hawkins becomes slave of agricultural land by her aunt, only her friendship with Billy and her dream to return to the castle of her childhood memories that make Marie-Ange endures. But the magic happens when Marie-Ange is 21 years old. She makes it back to the castle Chateau de Marmouton again and even get a chance to be the hostess which is the new owner of the castle, Comte Bernard de Beauchamp proposed her. But behind his proposal, Comte Bernard de Beauchamp keeps his hidden bad intentions to Marie-Ange Hawkins. In desperation and uncertainty areas around her, Marie- Ange has to find the faith and courage to take her last step to save her love ones and herself. -

From Safe Harbour to Privacy Shield Page 1 of 36

From Safe Harbour to Advances and shortcomings of thePrivacynew EU-US data Shield transfer rules IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service Authors: Shara Monteleone and Laura Puccio Members' Research Service January 2017 — PE 595.892 EN The October 2015 Schrems judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) declared invalid the European Commission’s decision on a 'Safe Harbour' for EU-US data transfer. The European Commission negotiated a new arrangement, known as Privacy Shield, and this new framework for EU-US data transfer was adopted in July 2016. This publication aims to present the context to the adoption of Privacy Shield as well as its content and the changes introduced. PE 595.892 ISBN 978-92-846-0369-5 doi:10.2861/09488 QA-06-16-293-EN-N Original manuscript, in English, completed in January 2017. Disclaimer The content of this document is the sole responsibility of the author and any opinions expressed therein do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. It is addressed to the Members and staff of the EP for their parliamentary work. Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy. © European Union, 2017. Photo credits: © vector_master / Fotolia. [email protected] http://www.eprs.ep.parl.union.eu (intranet) http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank (internet) http://epthinktank.eu (blog) From Safe Harbour to Privacy Shield Page 1 of 36 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In the 2015 Schrems case, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) declared the European Commission's 2000 decision on the 'adequacy' of the EU-US Safe Harbour (SH) regime invalid, thus allowing data transfers for commercial purposes from the EU to the United States of America (USA). -

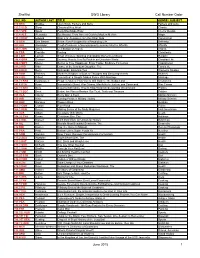

Shelflist DWO Library Call Number Order June 2015 1

Shelflist DWO Library Call Number Order CALL NO. AUTHOR LAST TITLE GENRE / SUBJECT 070 BRA Bradlee Life's Work: Fathers and Sons Fathers and sons 133.3 SLO Sloan Ghosts of Key West Ghosts 133.3 SPE Spear Feng Shui Made Easy Interior Design 133.4 ALE Alexander Spellbound: From Ancient Gods to Modern Merlins Magic 133.9 EDW Edward After Life: Answers From the Other Side Paranormal 170 DEN Den Besten Shine: Five Principles for a Rewarding Life Self-help 202 ALE Alexander Proof of Heaven: a Neurosurgeon's Journey Into the Afterlife Afterlife 235.3 JON Jones Celebration of Angels Angels 248 FRA Franklin Fasting Christianity 248 LAM Lamott Small Victories: Spotting Improbable Moments of Grace Religion 248.4 GRA Graham Journey: How to Live By Faith in an Uncertain World Christian Life 248.4 MEY Meyer Secret to True Happiness: Enjoy Today, Embrace Tomorrow Inspirational 291.2 KID Kidd Dance of the Dissident Daughter, The Family life 305.4 BER Berry Girlfriends: Enduring Ties Women's Studies 306 RAM Ramsey Mother's Wisdom: a Book of Thoughts and Encouragements Mothers 306.8 GIL Gilbert Committed: a Skeptic Makes Peace With Marriage Marriage 336.73 RAS Rasmussen People's Money: How Voters Will Balance the Budget and … Economics 341.6 RYA Ryan Yamashita's Ghost: War Crimes, MacArthur's Justice, and Command… War Crimes 342.73 BEC Beck Arguing With Idiots: How to Stop Small Minds and Big Government Politics 342.73 BEC Beck Broke: the Plan to Restore Our Trust, Truth and Treasure Politics 355 CLA Clancy Every Man a Tiger Military Science 355 WEI Weir