A Dictionary of Cultural and Critical Theory, Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bbc Music Jazz 4

Available on your digital radio, online and bbc.co.uk/musicjazz THURSDAY 10th NOVEMBER FRIDAY 11th NOVEMBER SATURDAY 12th NOVEMBER SUNDAY 13th NOVEMBER MONDAY 14th NOVEMBER JAZZ NOW LIVE WITH JAZZ AT THE MOVIES WITH 00.00 - SOMERSET BLUES: 00.00 - JAZZ AT THE MOVIES 00.00 - 00.00 - WITH JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 1) SOWETO KINCH CONTINUED JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 2) THE STORY OF ACKER BILK Clarke Peters tells the strory of Acker Bilk, Jamie Cullum explores jazz in films – from Al Soweto Kinch presents Jazz Now Live from Jamie celebrates the work of some of his one of Britain’s finest jazz clarinettists. Jolson to Jean-Luc Godard. Pizza Express Dean Street in London. favourite directors. NEIL ‘N’ DUD – THE OTHER SIDE JAZZ JUNCTIONS: JAZZ JUNCTIONS: 01.00 - 01.00 - ELLA AT THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL 01.00 - 01.00 - OF DUDLEY MOORE JAZZ ON THE RECORD THE BIRTH OF THE SOLO Neil Cowley's tribute to his hero Dudley Ella Fitzgerald, live at the Royal Albert Hall in Guy Barker explores the turning points and Guy Barker looks at the birth of the jazz solo Moore, with material from Jazz FM's 1990 heralding the start of Jazz FM. pivotal events that have shaped jazz. and the legacy of Louis Armstrong. archive. GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: GUY BARKER’S JAZZ COLLECTION: GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - 02.00 - GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - THE OTHER SIDE OF THE POND: 02.00 - TRUMPET MASTERS (PT. 2) JAZZ FESTIVALS (PT. 1) JAZZ ON FILM (PT. -

Ethnocentric Bias in African Philosophy Vis-A-Vis Asouzu’S Ibuanyidanda Ontology

Filosofia Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy, Culture and Religions ETHNOCENTRIC BIAS IN AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY VIS-A-VIS ASOUZU’S IBUANYIDANDA ONTOLOGY Umezurike John EZUGWU, M.A Department of Philosophy, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria Abstract This paper is of the view that it is not bad for the Africans to defend their philosophy and their origin, as against the claims and positions of the few African thinkers, who do not believe that African philosophy exists, and a great number of the Westerners, who see nothing meaningful in their thoughts and ideas, but in doing so, they became biased and elevated their philosophy and relegated other philosophies to the background. This charge of ethnocentrism against those who deny African philosophy can also be extended to those African philosophers who in a bid to affirm African philosophy commit the discipline to strong ethnic reduction. This paper using Innocent Asouzu’s Ibuanyidanda ontology, observes that most of the African scholars are too biased and self aggrandized in doing African philosophy, and as such have marred the beauty of African philosophy, just in the name of attaching cultural value to it. Innocent Asouzu’s Ibuanyidanda ontology is used in this paper to educate the Africans that in as much as the Westerners cannot do without them, they too cannot do without Westerners. This paper therefore, is an attempt to eradicate ethnocentrism in and beyond Africa in doing philosophy through complementarity and mutual understanding of realities, not in a polarized mindset but in relationship to other realities that exist. KEYWORDS: Ethnocentrism, Bias, Ibuanyidanda, Ontology, Complementarity, Ethnophilosophy. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Critical Universalism

Critical universalism Franziska Dubgen and Stefan Skupien, Paulin Hountondji: African Philosophy as Critical Universalism (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019). 192pp., €67,62 hb., 978 3 03001 994 5 During the extraordinarily intense debates on the future after independence in the 1960s, they embarked on the trajectory of modern African philosophy at the dawn arduous task of nation-building as the heads of state of African independence, Paulin J. Hountondji, along of their respective countries. By contrast, Hountondji with the likes of Kwasi Wiredu in Ghana, Henry O. Or- sought to return philosophy to a purer, less frenetic and uka in Kenya and Peter O. Bodunrin in Nigeria, played less politicised state and this entailed observing stricter a pivotal role. This group of professional philosophers, benchmarks of professionalisation. all of whom were obviously greatly influenced by their First, he turned to the discipline itself and found Western educations, was called the universalists. Houn- it wanting in terms of the levels of rigour he preferred. tondji was born in the Republic of Benin (then known as Ethnophilosophy, a discourse within the field that Houn- Dahomey) in 1942 and after his secondary school educa- tondji all but demolished, provided him with his decisive tion, he traveled to France where he studied philosophy entry into the world of established philosophical luminar- at the École normale supérieure under the supervision ies. Ethnophilosophy was pioneered by a Belgian cleric of professors such as Jacques Derrida, Louis Althusser, called Placide Frans Tempels (1906-1977) and a Rwandan Paul Ricoeur and Georges Cangulheim. priest, Alexis Kagame (1902-1981). -

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises a Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920S-1950S)

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 15 April 2019 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s- 1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Professor Stéphane Van Damme, European University Institute Professor Laura Downs, European University Institute Professor Catherine Tackley, University of Liverpool Professor Pap Ndiaye, SciencesPo © Veronica Chincoli, 2019 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I Veronica Chincoli certify that I am the author of the work “Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises: A Transnatioanl Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s). I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. I certify that this work complies with the Code of Ethics in Academic Research issued by the European University Institute (IUE 332/2/10 (CA 297). -

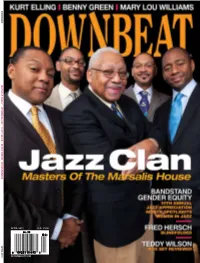

Downbeat.Com April 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. PRIL 2011 DOWNBEAT.COM A D OW N B E AT MARSALIS FAMILY // WOMEN IN JAZZ // KURT ELLING // BENNY GREEN // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2011 APRIL 2011 VOLume 78 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Maureen Flaherty ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Truth and Method, second, revised edition, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Translation revised by Joel Weinshcimer and Donald Marshall, (New York: Crossroad Publishers, 1989), pp.xxxviii + 594. Reviewed by Ted Vaggalis, University of Kansas. Truth and Method by H.-G. Gadamer is one of the great works in contemporary continental philosophy. However its importance has only recently begun to be widely appreciated by the American philosophical community. Its slow reception has been due primarily to its initial English translation, which was so poorly done that it contributed to frequent misunderstandings of Gadamer's work. This second edition, edited and revised by Joel Weinsheimer and Donald Marshall, is a welcome event that finally provides an accurate access to H.-G. Gadamer's magnum opus. Not only has the translation been cleaned up and made coherent, footnotes have been updated and new ones added that refer the reader to recent books and articles, by the author and others, that bear on the issues at hand. Gadamer himself has gone over the translation and added points of clarification as well, (xviii) Also, Weinsheimer and Marshall have written a brief preface that explains many of the key German words and concepts crucial for understanding Gadamer's analyses, (xi—xix) On the whole, this is a more critical translation that enables one to see how well Gadamer's account of philosophical hermeneutics has held up over the years since its publication in 1960. The new edition of Truth and Method is an excellent opportunity for recalling the book's overall argument. Perhaps the best place to start is with the correction of a common misunderstanding of Gadamer's project. -

Intimacy and Warmth In

A C T A K O R ANA VOL. 16, NO. 1, JUNE 2013: 177–197 A RESEARCH METHODOLOGY FOR KOREAN NEO-CONFUCIANISM1 By WEON-KI YOO This article suggests a new research methodology for Korean Neo-Confucianism. In order to do this, we need first to be clear about the nature of Korean Neo- Confucianism in relation to the question of whether it can be legitimately called philosophy in the Western sense of the term. In this article, I shall focus on the following questions: (1) Is there such a thing as world or universal philosophy? (2) Can Korean Neo-Confucianism be considered to be world philosophy? (3) What is the reason for the Western rejection of non-Western thought as philosophy? And (4) what conditions are required for Korean Neo-Confucianism to remain as a science which is understandable to the ordinary man of reason? I offer a negative answer to (1) for the reason that there is no consensus on the definition of philosophy itself. And if there is no such philosophy, we do not have to be concerned with (2). In relation to (3), I examine Defoort who blames the rejection of the existence or legitimacy of Chinese philosophy on Western chauvinism or ethnocentrism. Unlike Defoort, I consider that the rejection is rather due to Western indifference to, or ignorance of, East Asian traditions of thought. The main contention here is that, although there is no such thing as world philosophy, contemporary Korean Neo-Confucian scholars still need to satisfy a number of basic conditions to make Korean Neo-Confucianism a science worthy of discussion in the future. -

Bbc Music Jazz British and European Jazz (Pt

Available on your digital radio, online and bbc.co.uk/musicjazz THURSDAY 10TH NOVEMBER FRIDAY 11TH NOVEMBER SATURDAY 12TH NOVEMBER SUNDAY 13TH NOVEMBER MONDAY 14H NOVEMBER 00.00 - JAZZ AT THE MOVIES WITH 00.00 - JAZZ NOW LIVE WITH 00.00 - JAZZ AT THE MOVIES WITH 00.00 - THE LISTENING SERVICE JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 1) SOWETO KINCH CONTINUED JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 2) WITH TOM SERVICE Jamie Cullum explores jazz in films – from Soweto Kinch presents Jazz Now Live from Jamie celebrates the work of some Tom Service considers the art of musical Al Jolson to Jean-Luc Godard. Pizza Express Dean Street in London. of his favourite directors. improvisation with David Toop and Joelle Leandre. 00.30 - GREAT LIVES: THELONIOUS MONK Hannah Rothschild looks back at the life of jazz musician Thelonious Monk. 01.00 - NEIL ‘N’ DUD – THE OTHER SIDE 01.00 - ELLA AT THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL 01.00 - JAZZ JUNCTIONS: 01.00 - JAZZ JUNCTIONS: OF DUDLEY MOORE JAZZ ON THE RECORD THE BIRTH OF THE SOLO Neil Cowley’s tribute to his hero Dudley Moore, Ella Fitzgerald, live at the Royal Albert Hall Guy Barker explores the turning points and Guy Barker looks at the birth of the jazz solo with material from Jazz FM’s archive. in 1990 heralding the start of Jazz FM. pivotal events that have shaped jazz. and the legacy of Louis Armstrong. 02.00 - GUY BARKER’S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - GUY BARKER’S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - GUY BARKER’S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - GUY BARKER’S JAZZ COLLECTION: JAZZ FESTIVALS (PT. -

The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly to the Myth That These Books Were Explicit

VOLUME XXXIV The Historic New Orleans NUMBER 1 Collection Quarterly WINTER 2017 Shop online at www.hnoc.org/shop BLUE NOTES: The World of Storyville EVENT CALENDAR EXHIBITIONS & TOURS CREOLE CHRISTMAS HOUSE TOURS All exhibitions are free unless noted otherwise. Tour The Collection’s Williams Residence as part of the Friends of the Cabildo’s annual holiday home tour. CURRENT Tuesday–Thursday, December 27–29, 10 a.m.–4 p.m.; last tour begins at 3 p.m. Holiday Home and Courtyard Tour Tours depart from 523 St. Ann Street Through December 30; closed December 24–25 $25; tickets available through Friends of the Cabildo, (504) 523- 3939 Tuesday–Saturday, 10 and 11 a.m., 2 and 3 p.m. Sunday, 11 a.m., 2 and 3 p.m. “FROM THE QUEEN CITY TO THE CRESCENT CITY: CINCINNATI 533 Royal Street DECORATIVE ARTS IN NEW ORLEANS, 1825–1900” $5 admission; free for THNOC members Join us for a lecture with decorative arts historian Andrew Richmond and learn about the furniture, glass, and other goods that traveled down the Mississippi River to be sold in Clarence John Laughlin and His Contemporaries: A Picture and a New Orleans. Thousand Words Wednesday, February 1, 6–7:30 p.m. Through March 25, 2017 533 Royal Street Williams Research Center, 410 Chartres Street Free; reservations encouraged. Please visit www.hnoc.org or call (504) 523- 4662 for more information. Goods of Every Description: Shopping in New Orleans, 1825–1925 GUIDEBOOKS TO SIN LAUNCH PARTY Through April 9, 2017 Author Pamela D. Arceneaux will present a lecture and sign books as we launch THNOC's Williams Gallery, 533 Royal Street newest title, Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans. -

Jazzletter PO Box 240, Ojai CA

Gene Lees Jazzletter PO Box 240, Ojai CA. 93024-0240 April 1999 Vol. 18 No. 4 There is a widespread competence in young players, but they are The Immortal joker ofien as interchangeable as the parts on a GM pickup. They may Part Three be accomplished at the technical level, but too many are no more individual than Rich Little doing impressions. It is impossible in our time to perceive how Beethoven’s music The flatted fiflh chord and the minor-seventh-flat-five chord was perceived in his. This is true of artists generally We can were not new in westem music, but as composer Hale Smith points deduce it from the outrage visited on them by critics — Nicolas out, they were probably, for Monk and other jazz musicians, Slonirnsky’s Lexicon ofMusical Invective is a fascinating compen- discoveries, and thus became personal vocabulary. dium of such writings — but we can never actually feel the _ As" composers explored what we call western music over these original impact. last centuries, they expanded the vocabulary but they did not Even knowing how original Louis Annstrong was, we can invent, or re-invent it. However, this expansion, particularly in the never perceive him the way the thunderstruck young musicians of Romantic music of the nineteenth century, appeared to be.inven- his early days did. By the time many of us became aware of him, tion. Thus too with jazz, when Parker and Gillespie entered with Joe Glaser, his manager had manipulated him into position as an such éclat on the scene. -

Jazzletter PO Box 240, Ojai CA 93024-0240

Gene Lees jazzletter PO Box 240, Ojai CA 93024-0240 March 1999 Vol. 18 No. 3 The Immortal Joker vibrations. In the frequencies of light, they are processed as vision, interpreted as colors. We have no way of knowing whether you Part Two process the frequency of yellow into what I would call green and I process what you call blue into what I call red. Instruments, but not we, can detect vibrations in the radio and x-ray frequencies, leading to major advances in astronomy, although as has been observed—I think by Sir James .Jeans—the universe is not only stranger than you think, it is stranger than you can think. When one touches an object with a fingertip and finds it hot or cold, your nerve endings are merely reacting to the frequency of molecular motion within it. When we process vibrations in an approximate frequency range of I00 to 15,000’cycles, we call it sound, and by a process of its coherent organizing, we make what we call music. All beginning music students are taught that it is made up of- three elements, melody, harmony, and rhythm. This is a usage of convenience, like Newton’s physics, but in a higher sense it is wrong. Music consists of only one element, rhythm, for when you double the frequency of the vibration of A 440, to get A 880, you have jumped the tone up an octave, and other mathematical variants will give you all the tones of the scale. As for harmony, the use of several tones simultaneously, this too is a rhythmic phenomenon, for the beats put out by the second tone reinforce (or interfere with) those ofthe first.