Estoring Flows Into the Earth’S Arteries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

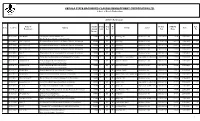

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

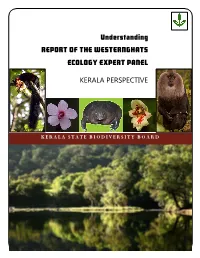

Understanding REPORT of the WESTERNGHATS ECOLOGY EXPERT PANEL

Understanding REPORT OF THE WESTERNGHATS ECOLOGY EXPERT PANEL KERALA PERSPECTIVE KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD Preface The Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel report and subsequent heritage tag accorded by UNESCO has brought cheers to environmental NGOs and local communities while creating apprehensions among some others. The Kerala State Biodiversity Board has taken an initiative to translate the report to a Kerala perspective so that the stakeholders are rightly informed. We need to realise that the whole ecosystem from Agasthyamala in the South to Parambikulam in the North along the Western Ghats in Kerala needs to be protected. The Western Ghats is a continuous entity and therefore all the 6 states should adopt a holistic approach to its preservation. The attempt by KSBB is in that direction so that the people of Kerala along with the political decision makers are sensitized to the need of Western Ghats protection for the survival of themselves. The Kerala-centric report now available in the website of KSBB is expected to evolve consensus of people from all walks of life towards environmental conservation and Green planning. Dr. Oommen V. Oommen (Chairman, KSBB) EDITORIAL Western Ghats is considered to be one of the eight hottest hot spots of biodiversity in the World and an ecologically sensitive area. The vegetation has reached its highest diversity towards the southern tip in Kerala with its high statured, rich tropical rain fores ts. But several factors have led to the disturbance of this delicate ecosystem and this has necessitated conservation of the Ghats and sustainable use of its resources. With this objective Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel was constituted by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) comprising of 14 members and chaired by Prof. -

Athirapally Hydel Electric Project

Athirapally Hydel Electric Project drishtiias.com/printpdf/athirapally-hydel-electric-project Why in News Recently, the Kerala government has approved the proposed Athirapally Hydro Electric Project (AHEP) on the Chalakudy river in Thrissur district of the state. There are already five dams for power and one for irrigation and it will be the seventh along the 145 km course of the Chalakudy river. Chalakudy River It originates in the Anamalai region of Tamil Nadu and is joined by its major tributaries Parambikulam, Kuriyarkutti, Sholayar, Karapara and Anakayam in Kerala. The river flows through Palakkad, Thrissur and Ernakulam districts of Kerala. It is the 4th longest river in Kerala and one of very few rivers of Kerala, which is having relics of riparian vegetation in substantial level. A riparian zone is the interface between land and a river or stream. Plant habitats and communities along the river margins and banks are called riparian vegetation, characterized by hydrophilic plants. It is the richest river in fish diversity perhaps in India as it contains 85 species of freshwater fishes out of the 152 species known from Kerala only. The famous waterfalls, Athirappilly Falls and Vazhachal Falls, are situated on this river. It merges with the Periyar River near Puthenvelikkara in Ernakulam district. Key Points 1/3 The total installed capacity of AHEP is 163 MW and the project is supposed to make use of the tail end water coming out of the existing Poringalkuthu Hydro Electric Project that is constructed across the Chalakudy river. AHEP envisages diverting water from the Poringalkuthu project as well as from its own catchment of 26 sq km. -

Patterns of Discovery of Birds in Kerala Breeding of Black-Winged

Vol.14 (1-3) Jan-Dec. 2016 newsletter of malabar natural history society Akkulam Lake: Changes in the birdlife Breeding of in two decades Black-winged Patterns of Stilt Discovery of at Munderi Birds in Kerala Kadavu European Bee-eater Odonates from Thrissur of Kadavoor village District, Kerala Common Pochard Fulvous Whistling Duck A new duck species - An addition to the in Kerala Bird list of - Kerala for subscription scan this qr code Contents Vol.14 (1-3)Jan-Dec. 2016 Executive Committee Patterns of Discovery of Birds in Kerala ................................................... 6 President Mr. Sathyan Meppayur From the Field .......................................................................................................... 13 Secretary Akkulam Lake: Changes in the birdlife in two decades ..................... 14 Dr. Muhamed Jafer Palot A Checklist of Odonates of Kadavoor village, Vice President Mr. S. Arjun Ernakulam district, Kerala................................................................................ 21 Jt. Secretary Breeding of Black-winged Stilt At Munderi Kadavu, Mr. K.G. Bimalnath Kattampally Wetlands, Kannur ...................................................................... 23 Treasurer Common Pochard/ Aythya ferina Dr. Muhamed Rafeek A.P. M. A new duck species in Kerala .......................................................................... 25 Members Eurasian Coot / Fulica atra Dr.T.N. Vijayakumar affected by progressive greying ..................................................................... 27 -

KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD on Athirappilly HE Project -163 MW Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP)

KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD Presentation on Athirappilly HE Project -163 MW before Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP) Chalakudy, Thrissur – 29 th January 2011 Athirappilly HE Project – 163 MW Athirappilly HEP ––LocationLocation Proposed project is located in Chalakudy river basin in Thrissur District, Kerala State Cascade Scheme with 94 % utilization of tail race discharges and spills from existing upstream reservoirs Projects up stream Sholayar Hydro Electric Project (54MW) Poringalkuthu Hydro Electric Project (48MW) KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD Athirappilly HE Project – 163 MW An overview Athirappilly project KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD Athirappilly HE Project – 163 MW Surge Dam Reservoir Tunnel Dam toe Power House Power House Vertical shaft Kannankuzhy thodu Kannankuzhythodu LONGITUDINAL SECTION Poringal dam Charpa Poringal Power Houses Poringal Adit Reservoir Tunnel Athirappilly Reservoir Dam toe PH To Sholayar Surge SH 21 Pokalappara Colony Dam Power House(2X80) MW Replacement Road To Chalakudy Athirappilly Falls Chalakudy River LAY OUT PLAN Athirappilly HE Project – 163 MW • The upstream most project is Sholayar which is operation since 1966. • The Sholayar project utilizes the water resources of Sholayar River a tributary of Chalakudy River • The tail water of Sholayar after generation flows to downstream Poringalkuthu reservoir. • The Poringalkuthu project is in operation for more than 50 years it is in the main river itself. Athirappilly HE Project – 163 MW • The tail water of Poringalkuthu discharges to Chalakudy -

Morphological and Genetic Evidence for Multiple Evolutionary Distinct

Morphological and Genetic Evidence for Multiple Evolutionary Distinct Lineages in the Endangered and Commercially Exploited Red Lined Torpedo Barbs Endemic to the Western Ghats of India Lijo John1,2., Siby Philip3,4,5., Neelesh Dahanukar6,7, Palakkaparambil Hamsa Anvar Ali5, Josin Tharian8, Rajeev Raghavan5,7,9,10*, Agostinho Antunes3,4* 1 Marine Biotechnology Division, Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), Kochi, India, 2 Export Inspection Agency (EIA), Kochi, India, 3 CIMAR/CIIMAR, Centro Interdisciplinar de Investigac¸a˜o Marinha e Ambiental, Rua dos Bragas, Porto, Portugal, 4 Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de Cieˆncias, Universidade do Porto, Rua do Campo Alegre, Porto, Portugal, 5 Conservation Research Group (CRG), St. Albert’s College, Kochi, India, 6 Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Pune, India, 7 Zoo Outreach Organization (ZOO), Coimbatore, India, 8 Department of Zoology, St. John’s College, Anchal, Kerala, India, 9 Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE), University of Kent, Canterbury, United Kingdom, 10 Research Group Zoology: Biodiversity & Toxicology, Center for Environmental Sciences, University of Hasselt, Diepenbeek, Belgium Abstract Red lined torpedo barbs (RLTBs) (Cyprinidae: Puntius) endemic to the Western Ghats Hotspot of India, are popular and highly priced freshwater aquarium fishes. Two decades of indiscriminate exploitation for the pet trade, restricted range, fragmented populations and continuing decline in quality of habitats has resulted in their ‘Endangered’ listing. Here, we tested whether the isolated RLTB populations demonstrated considerable variation qualifying to be considered as distinct conservation targets. Multivariate morphometric analysis using 24 size-adjusted characters delineated all allopatric populations. Similarly, the species-tree highlighted a phylogeny with 12 distinct RLTB lineages corresponding to each of the different riverine populations. -

Hydro Electric Power Dams in Kerala and Environmental Consequences from Socio-Economic Perspectives

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY – SEPT 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Hydro Electric Power Dams in Kerala and Environmental Consequences from Socio-Economic Perspectives. Liji Samuel* & Dr. Prasad A. K.** *Research Scholar, Department of Economics, University of Kerala Kariavattom Campus P.O., Thiruvananthapuram. **Associate Professor, Department of Economics, University of Kerala Kariavattom Campus P.O., Thiruvananthapuram. Received: June 25, 2018 Accepted: August 11, 2018 ABSTRACT Energy has been a key instrument in the development scenario of mankind. Energy resources are obtained from environmental resources, and used in different economic sectors in carrying out various activities. Production of energy directly depletes the environmental resources, and indirectly pollutes the biosphere. In Kerala, electricity is mainly produced from hydelsources. Sometimeshydroelectric dams cause flash flood and landslides. This paper attempts to analyse the social and environmental consequences of hydroelectric dams in Kerala Keywords: dams, hydroelectricity, environment Introduction Electric power industry has grown, since its origin around hundred years ago, into one of the most important sectors of our economy. It provides infrastructure for economic life, and it is a basic and essential overhead capital for economic development. It would be impossible to plan production and marketing process in the industrial or agricultural sectors without the availability of reliable and flexible energy resources in the form of electricity. Indeed, electricity is a universally accepted yardstick to measure the level of economic development of a country. Higher the level of electricity consumption, higher would be the percapitaGDP. In Kerala, electricity production mainly depends upon hydel resources.One of the peculiar aspects of the State is the network of river system originating from the Western Ghats, although majority of them are short rapid ones with low discharges. -

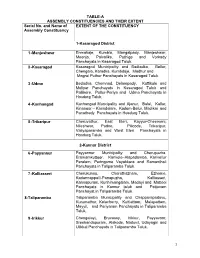

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Tourism Impact Assessment in Forested Land Using Geo Informatics

International Journal of Scientific Engineering and Research (IJSER) ISSN (Online): 2347-3878 (UGC Approved, Sr. No. 48096) Index Copernicus Value (2015): 62.86 | Impact Factor (2015): 3.791 Tourism Impact Assessment in Forested Land Using Geo Informatics Subin K. Jose*, Radhulakshmi V S Christ College (Autonomous), Thrissur, Kerala, India Abstract: The environment is being increasingly recognized as a key factor in tourism. The main purpose of tourism activities is the deployment of recreational facilities in an area with tourism potential. Tourism in Athirappilly is the largest industry, that providing several benefits to government and rural peoples. Tourism emergence, which lead naturally or consciously to the degradation of tourist heritage are represented by the natural disturbance of the surface areas of tourist interest and forest cover. The study focused on the impacts of tourism on forest area in Athirappilly region by comparing Landsat images from 1985 and 2012.The work was mapping the affected areas of forest as a result of tourism introduction based on physical characteristics. These are landscape or naturalness (land use/cover), topography (slope, drainage) and settlement size. At First, a list of tourism related criteria were developed. In present study raster based weightage method was carried out for the preparation of tourism disturbance map. GIS based techniques were used to measure the ranking of different criteria according those with the best potential for the study data utilized include survey of India to geographic maps. Subsequently, the forest disturbance map was created based on the combination of criteria and factors with their respective weights. The disturbed area of forest was classified as very high, high, moderate and low. -

A Flood Model for the Chalakudy River Area

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-8, Issue-9S4, July 2019 A Flood Model for the Chalakudy River Area Georg Gutjahr, Sachin Das that resulted in the death of about 400 or more persons during Abstract—The Kerala flood in the August of 2018 was the the past 90 years [2]. most severe flood in South India in almost a century. Kerala In this paper we consider the Chalakudy river area in was under high alert.14 districts were given red alert. Over 5 detail. The Chalakudy River is the fifth largest river in million people lost their homes and many of them were affected with fever and cold and several other diseases. After Kerala.The main part of the river flows through two districts: the flood, over 1 million people had to stay in relief camps for Ernakulam in the south and Thrissur in the north. The several months. Around 3200 relief camps were opened to Chalakudy river area was one of the most severely affected help the people. This works presents a model of the flood for areas during the flood. Uncommon precipitation events and Chalakudy river area. The area was one of the most severely flooding caused a great human loss and also resulted in affected areas during the flood. The model is a adaptation of a damage of ground-works. Hundreds of people from the area model that was introduced by Kourgialas and Karatzas for had to be evacuated and stayed in relief camps for multiple river basins in Greece. -

Western Ghats

Western Ghats From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "Sahyadri" redirects here. For other uses, see Sahyadri (disambiguation). Western Ghats Sahyadri सहहदररद Western Ghats as seen from Gobichettipalayam, Tamil Nadu Highest point Peak Anamudi (Eravikulam National Park) Elevation 2,695 m (8,842 ft) Coordinates 10°10′N 77°04′E Coordinates: 10°10′N 77°04′E Dimensions Length 1,600 km (990 mi) N–S Width 100 km (62 mi) E–W Area 160,000 km2 (62,000 sq mi) Geography The Western Ghats lie roughly parallel to the west coast of India Country India States List[show] Settlements List[show] Biome Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Geology Period Cenozoic Type of rock Basalt and Laterite UNESCO World Heritage Site Official name: Natural Properties - Western Ghats (India) Type Natural Criteria ix, x Designated 2012 (36th session) Reference no. 1342 State Party India Region Indian subcontinent The Western Ghats are a mountain range that runs almost parallel to the western coast of the Indian peninsula, located entirely in India. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is one of the eight "hottest hotspots" of biological diversity in the world.[1][2] It is sometimes called the Great Escarpment of India.[3] The range runs north to south along the western edge of the Deccan Plateau, and separates the plateau from a narrow coastal plain, called Konkan, along the Arabian Sea. A total of thirty nine properties including national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and reserve forests were designated as world heritage sites - twenty in Kerala, ten in Karnataka, five in Tamil Nadu and four in Maharashtra.[4][5] The range starts near the border of Gujarat and Maharashtra, south of the Tapti river, and runs approximately 1,600 km (990 mi) through the states of Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu ending at Kanyakumari, at the southern tip of India. -

Report of Rapid Impact Assessment of Flood/ Landslides on Biodiversity Focus on Community Perspectives of the Affect on Biodiversity and Ecosystems

IMPACT OF FLOOD/ LANDSLIDES ON BIODIVERSITY COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVES AUGUST 2018 KERALA state BIODIVERSITY board 1 IMPACT OF FLOOD/LANDSLIDES ON BIODIVERSITY - COMMUnity Perspectives August 2018 Editor in Chief Dr S.C. Joshi IFS (Retd) Chairman, Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram Editorial team Dr. V. Balakrishnan Member Secretary, Kerala State Biodiversity Board Dr. Preetha N. Mrs. Mithrambika N. B. Dr. Baiju Lal B. Dr .Pradeep S. Dr . Suresh T. Mrs. Sunitha Menon Typography : Mrs. Ajmi U.R. Design: Shinelal Published by Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram 2 FOREWORD Kerala is the only state in India where Biodiversity Management Committees (BMC) has been constituted in all Panchayats, Municipalities and Corporation way back in 2012. The BMCs of Kerala has also been declared as Environmental watch groups by the Government of Kerala vide GO No 04/13/Envt dated 13.05.2013. In Kerala after the devastating natural disasters of August 2018 Post Disaster Needs Assessment ( PDNA) has been conducted officially by international organizations. The present report of Rapid Impact Assessment of flood/ landslides on Biodiversity focus on community perspectives of the affect on Biodiversity and Ecosystems. It is for the first time in India that such an assessment of impact of natural disasters on Biodiversity was conducted at LSG level and it is a collaborative effort of BMC and Kerala State Biodiversity Board (KSBB). More importantly each of the 187 BMCs who were involved had also outlined the major causes for such an impact as perceived by them and suggested strategies for biodiversity conservation at local level. Being a study conducted by local community all efforts has been made to incorporate practical approaches for prioritizing areas for biodiversity conservation which can be implemented at local level.