Neatishead Conservation Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

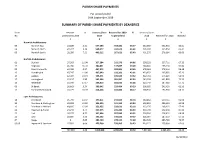

Parish Share Report

PARISH SHARE PAYMENTS For period ended 30th September 2019 SUMMARY OF PARISH SHARE PAYMENTS BY DEANERIES Dean Amount % Deanery Share Received for 2019 % Deanery Share % No Outstanding 2018 2019 to period end 2018 Received for 2018 received £ £ £ £ £ Norwich Archdeaconry 06 Norwich East 23,500 4.41 557,186 354,184 63.57 532,380 322,654 60.61 04 Norwich North 47,317 9.36 508,577 333,671 65.61 505,697 335,854 66.41 05 Norwich South 28,950 7.21 409,212 267,621 65.40 401,270 276,984 69.03 Norfolk Archdeaconry 01 Blofield 37,303 11.04 327,284 212,276 64.86 338,033 227,711 67.36 11 Depwade 46,736 16.20 280,831 137,847 49.09 288,484 155,218 53.80 02 Great Yarmouth 44,786 9.37 467,972 283,804 60.65 478,063 278,114 58.18 13 Humbleyard 47,747 11.00 437,949 192,301 43.91 433,952 205,085 47.26 14 Loddon 62,404 19.34 335,571 165,520 49.32 322,731 174,229 53.99 15 Lothingland 21,237 3.90 562,194 381,997 67.95 545,102 401,890 73.73 16 Redenhall 55,930 17.17 339,813 183,032 53.86 325,740 187,989 57.71 09 St Benet 36,663 9.24 380,642 229,484 60.29 396,955 243,433 61.33 17 Thetford & Rockland 31,271 10.39 314,266 182,806 58.17 300,933 192,966 64.12 Lynn Archdeaconry 18 Breckland 45,799 11.97 397,811 233,505 58.70 382,462 239,714 62.68 20 Burnham & Walsingham 63,028 15.65 396,393 241,163 60.84 402,850 256,123 63.58 12 Dereham in Mitford 43,605 12.03 353,955 223,631 63.18 362,376 208,125 57.43 21 Heacham & Rising 24,243 6.74 377,375 245,242 64.99 359,790 242,156 67.30 22 Holt 28,275 8.55 327,646 207,089 63.21 330,766 214,952 64.99 23 Lynn 10,805 3.30 330,152 196,022 59.37 326,964 187,510 57.35 07 Repps 0 0.00 383,729 278,123 72.48 382,728 285,790 74.67 03 08 Ingworth & Sparham 27,983 6.66 425,260 239,965 56.43 420,215 258,960 61.63 727,583 9.28 7,913,818 4,789,282 60.52 7,837,491 4,895,456 62.46 01/10/2019 NORWICH DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE LTD DEANERY HISTORY REPORT MONTH September YEAR 2019 SUMMARY PARISH 2017 OUTST. -

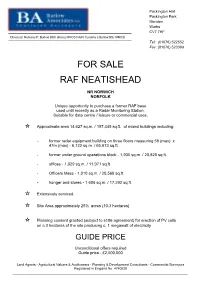

Raf Neatishead

Packington Hall Packington Park Meriden Warks CV7 7HF Directors: Nicholas P. Barlow BSC (Hons) FRICS FAAV Caroline J.Barlow BSc MRICS Tel: (01676) 522552 Fax: (01676) 523399 FOR SALE RAF NEATISHEAD NR NORWICH NORFOLK Unique opportunity to purchase a former RAF base used until recently as a Radar Monitoring Station. Suitable for data centre / leisure or commercial uses. l Approximate area 14,627 sq.m. / 157,445 sq.ft. of mixed buildings including: - former radar equipment building on three floors measuring 58 (max) x 47m (max) - 6,122 sq.m. / 65,873 sq.ft. - former under ground operations block - 1,935 sq.m. / 20,820 sq.ft. - offices - 1,029 sq.m. / 11,071 sq.ft. - Officers Mess - 1,910 sq.m. / 20,560 sq.ft. - hanger and stores - 1,606 sq.m. / 17,292 sq.ft. l Extensively serviced. l Site Area approximately 25½ acres (10.3 hectares) l Planning consent granted (subject to s106 agreement) for erection of PV cells on c.3 hectares of the site producing c. 1 megawatt of electricity GUIDE PRICE Unconditional offers required Guide price - £2,500,000 Land Agents - Agricultural Valuers & Auctioneers - Planning & Development Consultants - Commercial Surveyors Registered in England No. 4740520 RAF NEATISHEAD SCHEDULE OF PROPERTY No. Building Sq.M. Sq.Ft. (gross ext.) (gross ext.) 1 Property Management 335 3,606 2 Garages (ex small archive store) 69 74 3 Store with lean-to 24 (+ 20) 258 (+ 215) 4 Station Headquarters and Headquarters 698 7,511 Extension 5 Combined Mess 1,910 20,560 6 Squash Courts and Changing Rooms 163 1,754 7 Old Fitness Suite 110.5 1,189 8 Bungalow 466 5,021 9 Former Medical Centre and Dental Centre 146 1,572 10 Office Building 331 3,560 11 MT Main Building and stores 750 8,076 12 MT Hangar 856 9,216 13 Gymnasium 513 5,524 14 Gym Changing Rooms 178.5 1,921 15 Building no longer in existence - - 16 R12 Two storey (and basement) former radar 6,122 * 65,873 * equipment building 58m x 47m 17 R3 Underground former operations block 1,935 * 20,820 * Totals 14,627 157,445 * Approximate areas for indicative purposes only, as supplied by the RAF. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

Georgian Farmhouse in Unspoilt Position

Georgian farmhouse in unspoilt position Grove House, Irstead, Norfolk Freehold Entrance hall • Drawing room • Dining room • Kitchen/ breakfast room with Aga • Study • Utility room • Old dairy Studio • Cloakroom/WC • Cellar • Six bedrooms • Family bathroom • Shower room • Outbuildings including barn Garaging • Mooring rights nearby • Mature gardens and grounds in all about 0.48 of an acre The Property traditionally constructed of red Grove House is a most brick and providing garaging attractive Grade II listed and workshop/storage space. Georgian farmhouse of circa The land in all extends to about 1820 with earlier origins 0.48 of an acre. believed to date to the 17th century. The house has elegant Situation and well-proportioned rooms Irstead is a small unspoilt rural typical of the period and lit by hamlet lying between Horning fine sash windows. Much and Neatishead. The village of period detail remains Neatishead is about half a mile throughout the house which and has a community village was acquired by the current shop and traditional pub. There owners in 1991 and who carried is a new village hall which hosts out a sensitive and faithful a number of local events. The programme of renovation and village of Irstead itself is about restoration. a mile and there is access via a boardwalk with fine walks Outside around the periphery of Barton The house is approached by a Broad nearby. The bustling gravelled drive to the east of riverside village of Horning the house which finishes in a (about two miles) has further large gravelled turning and everyday shopping including a parking space to the north of delicatessen, three public the house. -

Church Officers

2 To Advertise Tel: 01603 782466 or e-mail [email protected] CHURCH OFFICERS in Wroxham Hoveton Belaugh Tunstead & Neatishead Church of England Rector Revd Elizabeth Jump The Vicarage 11 Church Lane Wroxham NR12 8SH Tel: 01603 784150 [email protected] www.wroxhambenefice.org Associate Priests Revd Fr Tim Gosden Tel: 07500 864929 Revd Barry Furness Tel: 01603 782919 Reader Veronica Mowat Tel: 01603 782489 [email protected] Authorised Worship Assistants Mrs Sue Cobb Tel: 01603 783387 Mrs Sandy Lines Tel: 01603 782282 Churchwardens Wroxham St Mary Rod Stone Tel: 782735 Hoveton St Peter Sandy Lines Tel: 782282 [email protected] Tunstead St Mary John Carter Tel: 01692 536380 Barbara Wharton Tel: 01603 738958 United Reformed Church Minister Rev Bruno Boldrini 94 Welsford Road NR4 6QH Tel: 01603 458873 Secretary Mrs Lynne Howard Tel: 01603 738835 [email protected] Contact for JAM (Sunday School) Mr Chris Billing Tel: 783992 [email protected] Roman Catholic Church Parish Priest Fr. James Walsh The Presbytery 4 Norwich Road North Walsham NR28 9JP Tel: 01692 403258 www.sacredheartnorthwalsham.com Sacristan Tryddyn Horning Road West Hoveton NR12 8QJ Tel: 782758 Baptist Church Neatishead Baptist Church, Chapel Road, Neatishead, NR12 8YF ww.neatisheadbaptist.org.uk Tel: 01603 738893 Pastor Ian Bloomfield [email protected] Contact Church Secretary [email protected] In Association with Broadgrace Church Minister John Hindley Tel: 737974 [email protected] Inputs by 15th Please 3 From the Rector the Revd. Liz Jump is has been a strange year, to say the least. As I write this, we are in the second lockdown – words that would have meant nothing just a year ago, and would have been difficult to even explain. -

North Norfolk District Council (Alby

DEFINITIVE STATEMENT OF PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY NORTH NORFOLK DISTRICT VOLUME I PARISH OF ALBY WITH THWAITE Footpath No. 1 (Middle Hill to Aldborough Mill). Starts from Middle Hill and runs north westwards to Aldborough Hill at parish boundary where it joins Footpath No. 12 of Aldborough. Footpath No. 2 (Alby Hill to All Saints' Church). Starts from Alby Hill and runs southwards to enter road opposite All Saints' Church. Footpath No. 3 (Dovehouse Lane to Footpath 13). Starts from Alby Hill and runs northwards, then turning eastwards, crosses Footpath No. 5 then again northwards, and continuing north-eastwards to field gate. Path continues from field gate in a south- easterly direction crossing the end Footpath No. 4 and U14440 continuing until it meets Footpath No.13 at TG 20567/34065. Footpath No. 4 (Park Farm to Sunday School). Starts from Park Farm and runs south westwards to Footpath No. 3 and U14440. Footpath No. 5 (Pack Lane). Starts from the C288 at TG 20237/33581 going in a northerly direction parallel and to the eastern boundary of the cemetery for a distance of approximately 11 metres to TG 20236/33589. Continuing in a westerly direction following the existing path for approximately 34 metres to TG 20201/33589 at the western boundary of the cemetery. Continuing in a generally northerly direction parallel to the western boundary of the cemetery for approximately 23 metres to the field boundary at TG 20206/33611. Continuing in a westerly direction parallel to and to the northern side of the field boundary for a distance of approximately 153 metres to exit onto the U440 road at TG 20054/33633. -

NORFOLK. • Witton & Worstead

518 NORTH W ALSHAM, NORFOLK. • Witton & Worstead. Rapping division-Brunstead, Medical Officer & Public Vaccinator, North Walsham Catfield, East Ruston, Happisburgh, Hempstead-cum District, Smallburgh Union, Sidney Hope Harrison Eccles, Hiclding, Horsey, Ingham, Lessingham, Lud M.R.C.S.Eng., L.R.C.P.Lond. Aylsham road ham, Palling, Potter Heigham, Stalham, Sutton, Wal Medical Officer & Public Vaccinator, Southrepps District, cott & W a:xham Erpingham Union, John Shepheard B.A.,M.R.C.S.Eng., L.R.C.P.Lond. Cromer road 1 NORTH WALSHAM SUB-COMMITTEE OF NORFOLK Registrar of Marriages & Deputy for Births & Deaths LOCAL PENSION COMMITTEE. for the Smallburgh District, Ernest W. Gregory, ' The following places are included in the Sub-District: Excelsior house, -King's Arms street Alby, Aldborough, Antingham, Bacton, Banningham, Relieving & Vaccination Officer, Tunstead District & ,Barton Turf, Beeston St. Lawrence, Bradfield, Brum Registrar of Births & Deaths, North Walsham District;, stead, Burgh, Calthorpe, Catfield, Colby, Crostwight, "Smallburgh Union, George Boult Hewitt, Yarmouth rd Dilham, Ea~t Ruston, Edingthorpe, Erpingham, Fel Superintendent Registrar of Smallburgh Union, Fairfax mingham, Gimingham, Gunton, Happisburgh, Hemp Davies. Grammar School road stead-cum-Eccles, Hickling, Honing, Ingham, Ingworth, PLACES OF WORSHIP, with times of Services. Irstead, Knapton, Lessingham, Mundesley, Neatishead, _N orthrepps, North Walsham, Overstrand, Oxnead, St. Nicholas Church, Rev. Robert Aubrey Aitken M.A. Paston, Ridlington, Sidestrand, Skeyton, Sea Palling, vicar & rural dean; Rev. Tom Harry Cromwell Nash Smallburgh, Southrepps, Suffield, Sutton, Swafield, Th.A.K.C. curate; 8 & II a.m. & 3 & 6.30 p.m. ; Stalham, Swanton Abbott, Thorpe Market, Thwaite, mon. wed. & fri. li a.m. ; tues. thurs. -

Planning Committee AGENDA Friday 18 August 2017 10.00Am 1

Planning Committee AGENDA Friday 18 August 2017 10.00am Page 1. Appointment of Chairman 2. Appointment of Vice-Chairman 3. To receive apologies for absence and introductions 4. To receive declarations of interest 5. To receive and confirm the minutes of the previous 4 – 14 meeting held on 21 July 2017 (herewith) 6. Points of information arising from the minutes 7. To note whether any items have been proposed as matters of urgent business MATTERS FOR DECISION 8. Chairman’s Announcements and Introduction to Public Speaking Please note that public speaking is in operation in accordance with the Authority’s Code of Conduct for Planning Committee. Those who wish to speak are requested to come up to the public speaking desk at the beginning of the presentation of the relevant application 9. Request to defer applications included in this agenda and/or to vary the order of the Agenda To consider any requests from ward members, officers or applicants to defer an application included in this agenda, or to vary the order in which applications are considered to save unnecessary waiting by members of the public attending 10. To consider applications for planning permission including matters for consideration of enforcement of planning control: 1 Page • BA/2017/0103/OUT Hedera House, the Street, Thurne 15 – 45 • BA/2017/0224/FUL Land to North of Cemetery, Pyebush 46 – 56 Lane, Acle • BA/2017/0179/FUL Burghwood Barns, Burghwood Road, 57 – 72 Ormesby St Michael • BA/2017/0193/HOUSEH Freshfields, St Olaves 73 – 81 11. Enforcement of Planning Control 82 – 84 Enforcement Item for Noting: No.1 & No.2 Manor Farm House, Oby Report by Enforcement Officer (herewith) 12. -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED Election of Parish

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED North Norfolk Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Councillor for Aldborough and Thurgarton Reason why Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer no longer nominated* BAILLIE The Bays, Chapel Murat Anne M Tony Road, Thurgarton, Norwich, NR11 7NP ELLIOTT Sunholme, The Elliott Ruth Paul Martin Green, Aldborough, NR11 7AA GALLANT Spring Cottage, The Elliott Paul M David Peter Green, Aldborough, NR11 7AA WHEELER 4 Pipits Meadow, Grieves John B Jean Elizabeth Aldborough, NR11 7NW WORDINGHAM Two Oaks, Freeman James H J Peter Thurgarton Road, Aldborough, NR11 7NY *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. The persons above against whose name no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. Dated: Friday 10 April 2015 Sheila Oxtoby Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Electoral Services, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9EN STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED North Norfolk Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Councillor for Antingham Reason why Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer no longer nominated* EVERSON Margra, Southrepps Long Trevor F Graham Fredrick Road, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP JONES The Old Coach Independent Bacon Robert H Graham House, Antingham Hall, Cromer Road, Antingham, N. Walsham, NR28 0NJ LONG The Old Forge, Everson Graham F Trevor Francis Elderton Lane, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NR LOVE Holly Cottage, McLeod Lynn W Steven Paul Antingham Hill, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0NH PARAMOR Field View, Long Trevor F Stuart John Southrepps Road, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. -

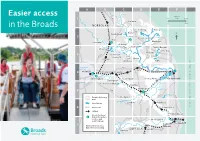

Easier Access Guide

A B C D E F R Ant Easier access A149 approx. 1 0 scale 4.3m R Bure Stalham 0 7km in the Broads NORFOLK A149 Hickling Horsey Barton Neatishead How Hill 2 Potter Heigham R Thurne Hoveton Horstead Martham Horning A1 062 Ludham Trinity Broads Wroxham Ormesby Rollesby 3 Cockshoot A1151 Ranworth Salhouse South Upton Walsham Filby R Wensum A47 R Bure Acle A47 4 Norwich Postwick Brundall R Yare Breydon Whitlingham Buckenham Berney Arms Water Gt Yarmouth Surlingham Rockland St Mary Cantley R Yare A146 Reedham 5 R Waveney A143 A12 Broads Authority Chedgrave area river/broad R Chet Loddon Haddiscoe 6 main road Somerleyton railway A143 Oulton Broad Broads National Park information centres and Worlingham yacht stations R Waveney Carlton Lowesto 7 Grid references (e.g. Marshes C2) refer to this map SUFFOLK Beccles Bungay A146 Welcome to People to help you Public transport the Broads National Park Broads Authority Buses Yare House, 62-64 Thorpe Road For all bus services in the Broads contact There’s something magical about water and Norwich NR1 1RY traveline 0871 200 2233 access is getting easier, with boats to suit 01603 610734 www.travelinesoutheast.org.uk all tastes, whether you want to sit back and www.broads-authority.gov.uk enjoy the ride or have a go yourself. www.VisitTheBroads.co.uk Trains If you prefer ‘dry’ land, easy access paths and From Norwich the Bittern Line goes north Broads National Park information centres boardwalks, many of which are on nature through Wroxham and the Wherry Lines go reserves, are often the best way to explore • Whitlingham Visitor Centre east to Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft. -

The Local Government Boundary Commission for England Electoral Review of North Norfolk

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF NORTH NORFOLK Final recommendations for ward boundaries in the district of North Norfolk April 2017 Sheet 1 of 1 This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2017. Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. KEY TO PARISH WARDS CROMER CP WELLS-NEXT-THE-SEA CP A SUFFIELD PARK STIFFKEY CP MORSTON CP B TOWN BLAKENEY CP SALTHOUSE WARHAM CP CP SHERI COASTAL CLEY NEXT NGHAM NORTH J WELLS WITH HOLKHAM THE SEA CP FAKENHAM CP SHERINGHAM C NORTH CP BEESTON REGIS D SOUTH HOLKHAM CP WIVETON WEYBOURNE CP SHERINGHAM & THE RUNTONS CP K BEESTON KELLING CP SOUTH REGIS CP RUNTON CP CROMER TOWN SUFFIELD NORTH WALSHAM CP UPPER SHERINGHAM CP PARK CROMER LANGHAM CP B CP E EAST A F NORTH OVERSTRAND CP G TOWN CENTRE EAST H TOWN CENTRE WEST BINHAM CP LETHERINGSETT HIGH EAST WITH KELLING BECKHAM CP I WEST WIGHTON CP GLANDFORD CP CP AYLMERTON CP PRIORY SIDESTRAND BODHAM CP WEST POPPYLAND BECKHAM FELBRIGG CP CP SHERINGHAM CP CP HOLT NORTHREPPS CP J NORTH HOLT CP FIELD DALLING CP TRIMINGHAM K SOUTH CP GRESHAM CP WALSINGHAM CP ROUGHTON CP GRESHAM BACONSTHORPE SUSTEAD CP -

Norfolk Vanguard Limited Document Reference: 5.1 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(Q)

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 12.3 Scoping Area and PCZ Mailing Area Map Applicant: Norfolk Vanguard Limited Document Reference: 5.1 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(q) Date: June 2018 Revision: Version 1 Author: BECG Photo: Kentish Flats Offshore Wind Farm This page is intentionally blank. Norfolk Vanguard Offs hore Wind Farm Appendices 585000 590000 595000 600000 605000 610000 615000 620000 625000 630000 635000 640000 Thornage Mundesley Indicative Onshore Elements of Brinton Hunworth Thorpe Market theSouth Project Creake (incl. Landfall, CableHoughton Hanworth St Giles Gunthorpe Stody Relay Station Zones, and Project Plumstead Matlaske Thurgarton Trunch F Great Snoring 335000 East Barsham Briningham Edgefield Alby Hill Knapton 335000 Substation Zone) Thursford West Barsham Little Bacton Ramsgate Barningham Wickmere Primary Consultation Zone Briston Antingham Little Swanton Street Suffield Snoring Novers Swafield Historic Scoping SculthorpeArea Barney Calthorpe Parish Boundaries (OS, 2017) Kettlestone Fulmodeston Itteringham Saxthorpe North Walsham Dunton Tattersett Fakenham Corpusty Crostwight 330000 330000 Hindolveston Thurning Hempton Happisburgh Common Oulton Tatterford Little Stibbard Lessingham Ryburgh Wood Norton Honing East Toftrees Great Ryburgh Heydon Bengate Ruston Guestwick Wood Dalling Tuttington Colkirk Westwick Helhoughton Aylsham Ingham Guist Burgh Skeyton Worstead Stalham next Aylsham East Raynham Oxwick Foulsham Dilham Brampton Stalham Green 325000 325000 Marsham Low Street Hickling