The River Adur and the Knepp Estate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncontested Parish Election 2015

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Horsham District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Parish of Amberley on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Parish of Amberley. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ALLINSON Garden House, East Street, Hazel Patricia Amberley, Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9NN CHARMAN 9 Newland Gardens, Amberley, Jason Rex Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9FF CONLON Stream Barn, The Square, Geoffrey Stephen Amberley, Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9SR CRESSWELL Lindalls, Church Street, Amberley, Leigh David Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9ND SIMPSON Downlands Loft, High Street, Tim Amberley, Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9NL UREN The Granary, East Street, Geoffrey Cecil Amberley, Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9NN Dated Friday 24 April 2015 Tom Crowley Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Horsham District Council, Park North, North Street, Horsham, West Sussex, RH12 1RL NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Horsham District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Parish of Ashington on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Parish of Ashington. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) CLARK Spindrift, Timberlea Close, Independent Neville Ernest Ashington, Pulborough, West Sussex, RH20 3LD COX 8 Ashdene Gardens, Ashington, Sebastian Frederick -

Boating on Sussex Rivers

K1&A - Soo U n <zj r \ I A t 1" BOATING ON SUSSEX RIVERS NRA National Rivers Authority Southern Region Guardians of the Water Environment BOATING ON SUSSEX RIVERS Intro duction NRA The Sussex Rivers have a unique appeal, with their wide valleys giving spectacular views of Chalk Downs within sight and smell of the sea. There is no better way to enjoy their natural beauty and charm than by boat. A short voyage inland can reveal some of the most attractive and unspoilt scenery in the Country. The long tidal sections, created over the centuries by flashy Wealden Rivers carving through the soft coastal chalk, give public rights of navigation well into the heartland of Sussex. From Rye in the Eastern part of the County, small boats can navigate up the River Rother to Bodiam with its magnificent castle just 16 miles from the sea. On the River Arun, in an even shorter distance from Littlehampton Harbour, lies the historic city of Arundel in the heart of the Duke of Norfolk’s estate. But for those with more energetic tastes, Sussex rivers also have plenty to offer. Increased activity by canoeists, especially by Scouting and other youth organisations has led to the setting up of regular canoe races on the County’s rivers in recent years. CARING FOR OUR WATERWAYS The National Rivers Authority welcomes all river users and seeks their support in preserving the tranquillity and charm of the Sussex rivers. This booklet aims to help everyone to enjoy their leisure activities in safety and to foster good relations and a spirit of understanding between river users. -

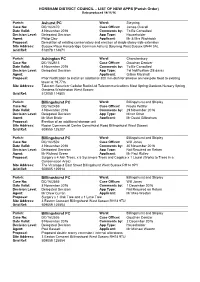

HORSHAM DISTRICT COUNCIL – LIST of NEW APPS (Parish Order) Data Produced 14/11/16

HORSHAM DISTRICT COUNCIL – LIST OF NEW APPS (Parish Order) Data produced 14/11/16 Parish: Ashurst PC Ward: Steyning Case No: DC/16/2470 Case Officer: James Overall Date Valid: 8 November 2016 Comments by: To Be Consulted Decision Level: Delegated Decision App Type: Householder Agent: Philip Clay Applicant: Mr & Mrs Wightwick Proposal: Demolition of existing conservatory and erection of single storey side extension Site Address: Sussex Place Horsebridge Common Ashurst Steyning West Sussex BN44 3AL Grid Ref: 518078 114671 Parish: Ashington PC Ward: Chanctonbury Case No: DC/16/2513 Case Officer: Oguzhan Denizer Date Valid: 4 November 2016 Comments by: To Be Consulted Decision Level: Delegated Decision App Type: Tel Notification (28 days) Agent: Applicant: Gillian Marshall Proposal: Prior Notification to install an additional 300 mm dish for airwave on new pole fixed to existing tower at 19.77m Site Address: Telecom Securicor Cellular Radio Ltd Telecommunications Mast Spring Gardens Nursery Spring Gardens Washington West Sussex Grid Ref: 512059 114805 Parish: Billingshurst PC Ward: Billingshurst and Shipley Case No: DC/16/2459 Case Officer: Nicola Pettifer Date Valid: 4 November 2016 Comments by: 29 November 2016 Decision Level: Delegated Decision App Type: Minor Other Agent: Mr Matt Bridle Applicant: Mr David Gillingham Proposal: Erection of an additional storage unit Site Address: Rosier Commercial Centre Coneyhurst Road Billingshurst West Sussex Grid Ref: 509555 125207 Parish: Billingshurst PC Ward: Billingshurst and Shipley Case No: DC/16/2502 -

A Medieval Moated Site and Manorial Complex Rediscovered Through Lidar at Broadbridge Heath, West Sussex

SUSSEX ARCHAEOLOGICAL COLLECTIONS 155 (2017), 111–117 ◆A medieval moated site and manorial complex rediscovered through LiDAR at Broadbridge Heath, West Sussex By Andrew Margetts Combining historic landscape analysis with freely available LiDAR data has revealed a forgotten medieval moated site. The results also identified the probable medieval site of Broadbridge Mill as well as highlighting the potential of this form of survey for Wealden site recognition. INTRODUCTION (Margetts in prep.; Fig. 1). Amongst the reasonably dense multi-period remains was evidence of a well hen Gardiner conducted a survey preserved medieval landscape including several sites and review of the archaeology of the of potential ‘manorial’ status. The earliest of these WWeald over 25 years ago (1990) it was dated from the late 10th or early 11th century and clear that the archaeology of the entire pay (taken may relate to a lost holding mentioned in Domesday from the French term for an area of culturally and (Morris 1976, 11.58). The application of the label environmentally distinctive territory, country ‘manor’ prior to 1086 is essentially an anachronism and region) was little studied. This was as true as the Latin word manerium from which it derives for the Middle Ages, traditionally viewed as the is wholly a Norman introduction (Lewis 2012). time of most fundamental Wealden landscape Though these sites appeared to straddle the change (Witney 1976; Everitt 1986; Brandon 1974; Conquest the term ‘estate centre’ is more correct 2003), as it was for the prehistoric and Romano- as at least one of the holdings appears to have been British periods. -

NOTICE of POLL Election of a County Councillor

NOTICE OF POLL West Sussex County Council Election of a County Councillor for Billingshurst Division Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Billingshurst Division will be held on Thursday 4 May 2017, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BROWN 6 Woodpeckers, Labour Party Peter H Williams (+) Anthony M Parker (++) Robert William Southwater, Jonathan C Austin Susie V Clitheroe Horsham, Caroline J Butler Susan Furness West Sussex, Stuart D C Brown Lee Strachan John E Marder Swee Lian Marder RH13 9AA GREENWOOD 2 Pathfield Cottages, Liberal Democrats Katarzyna M James G Nicholls (++) Richard John Cross Lane, Greenwood (+) Robert J H Hammond Barns Green, Philippa D Hammond Kathleen M Welch Horsham, Daphne Chennell Callum A m Hilder Barry P Welch Alan Lambkin West Sussex, Carolyn P Lambkin RH13 0QF HARPER Filbuds Cottage, UK Independence Alison J Standring (+) Gail Playford (++) Graham Hartridge Stane Street, Party (UKIP) Luke A Pody Colin N Winckler Adversane, Nicholas C Mason Wayne R Playford Billingshurst, Raymond T Playford Marion G Ireland Henry Ayre Heather J Partridge West Sussex, RH14 9JP JUPP Daniels Farm, The Conservative Party Hariot K Anniss (+) Gordon A Lindsay (++) Amanda Jane West Chiltington Lane, Candidate David J Meadows Timothy J Bulmer Coneyhurst, Beverley J Sperring Jean Taylor Billingshurst, David N Currie Denis A Critchley Phyllis Davies Owen J Davies West Sussex, RH14 9DX 4. -

Area Infrastructure Plan

Agenda Item No. 8 Appendix A Chanctonbury County Local Committee Infrastructure Plan Prioritisation Infrastructure Plan Proposed Priorities: • Steyning - improvements to improve safety at the junction of A283 Steyning Bypass with Horsham Road, going into/from Steyning and into/from Ashurst. • Bramber - The Street (o/s St Marys House) and near car park access. Traffic Management (Alternations) - Removal of two speed bumps, plus a chicane with raised road surface level and a narrowed road entrance together with a smoothing of the other bumps considered too high with traffic vibrations from buses. • Ashington - Install a VAS at the entrance to the village on Billingshurst Rd. plus anti skid surfacing on the bend at Spears Hill. • Amberley – Extension of 40mph speed limit eastwards on The Turnpike to approximately the far side of the football field and install 'Gateways'. • Henfield - Installation of a speed indication device on London Road. • Henfield - Gateway Features and road safety points on the B2116 at Backlands. • Thakeham – New footpath– Storrington Road B2139, eastside between, just north of the southern junction with Crescent Rise – new section of footway by shop frontages to provide continuous north/south pedestrian link. • Pulborough – Lower Street Regeneration Scheme – Support the delivery of highway associated works, including the potential introduction of revised waiting restrictions. • Pulborough - New Railway line Footbridge (A29) London Road - progress any preferred option in line with feasibility study recommendations. Items highlighted for future Infrastructure Plan Prioritisation and/or to be progressed in other ways: • Ashington - Review parking issues at Church Lane / Foster Lane and put together scheme to improve. • Ashington - Review Meiros Way/Rectory Lane junction priorities. -

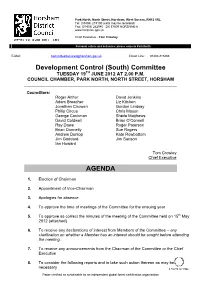

Development Control (South) Committee TUESDAY 19TH JUNE 2012 at 2.00 P.M

Park North, North Street, Horsham, West Sussex, RH12 1RL Tel: (01403) 215100 (calls may be recorded) Fax: (01403) 262985 DX 57609 HORSHAM 6 www.horsham.gov.uk Chief Executive - Tom Crowley Personal callers and deliveries: please come to Park North E-Mail: [email protected] Direct Line: 01403 215465 Development Control (South) Committee TUESDAY 19TH JUNE 2012 AT 2.00 P.M. COUNCIL CHAMBER, PARK NORTH, NORTH STREET, HORSHAM Councillors: Roger Arthur David Jenkins Adam Breacher Liz Kitchen Jonathan Chowen Gordon Lindsay Philip Circus Chris Mason George Cockman Sheila Matthews David Coldwell Brian O’Connell Ray Dawe Roger Paterson Brian Donnelly Sue Rogers Andrew Dunlop Kate Rowbottom Jim Goddard Jim Sanson Ian Howard Tom Crowley Chief Executive AGENDA 1. Election of Chairman 2. Appointment of Vice-Chairman 3. Apologies for absence 4. To approve the time of meetings of the Committee for the ensuing year 5. To approve as correct the minutes of the meeting of the Committee held on 15th May 2012 (attached) 6. To receive any declarations of interest from Members of the Committee – any clarification on whether a Member has an interest should be sought before attending the meeting. 7. To receive any announcements from the Chairman of the Committee or the Chief Executive 8. To consider the following reports and to take such action thereon as may be necessary Paper certified as sustainable by an independent global forest certification organisation Head of Planning & Environmental Services Appeals Applications for determination by Committee -

Community Youth Work Quarterly Report Form Youth Worker: Emma Edwards Area: Steyning, Upper Beeding, Bramber & Ashurst Date: 25Th February 2015

Community Youth Work Quarterly Report Form Youth worker: Emma Edwards Area: Steyning, Upper Beeding, Bramber & Ashurst Date: 25th February 2015 Main areas of work since last report Outcomes / Achievements Youth Café Youth café continues to run on a Monday night in Upper Beeding. We have seen a drop in numbers lately and have been delivering flyers and working on an advertising drive to get more young people along. We would particularly like to see the younger end year 9 pupils. We currently have two young people working putting together Youth Neighbourhood plan a youth survey to go out following the neighbourhood plan. We have now had two meetings and the young people have completed writing the survey really to be tested before distributing. The key areas they felt were important were housing, community and transport and so have focused on these. Youth Voice It is hoped that following the youth neighbourhood plan a new youth voice group can be established starting with the young people involved in writing the questionnaire. Emma has been approached by The Steyning Downlands Scheme to start a new Youth Vision group for young peoples input, as well as The Community partnership who wish to gather a group of young people to give input and participate into their work. It is hoped that these different groups can be one in the same and bring together a youth council for the area. Emma has been in touch with a pupil of Steyning Grammar school who has just been elected Member of Youth Parliament for East Arun, Adur Worthing and Member of Youth Cabinet for Steyning and Storrington. -

7-Night South Downs Gentle Walking Holiday

7-Night South Downs Gentle Walking Holiday Tour Style: Gentle Walks Destinations: South Downs & England Trip code: AWBEW-7 1 & 2 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW This easier variation of our best-selling Guided Walking holidays is the perfect way to enjoy a gentle exploration of the South Downs. The choice of three guided walks includes a very short walk of 3 or 4 miles. Enjoy the rolling hills and magnificent chalk cliffs of the South Downs. This wildlife-rich chalk downland is a colourful tapestry of historic villages, thatched cottages, pastoral landscapes of sweeping cornfields and market towns. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking and 1 free day • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on full day walks to discover the varied beauty of the South Downs on foot • Admire panoramic sea and cliff views • Let a local leader bring classic routes and offbeat areas to life • Enjoy magnificent South Downs coastal scenery • Visit charming English villages • Look out for wildlife, find secret corners and learn about the rich history • A relaxed pace of discovery in a sociable group keen to get some fresh air in one of England’s most beautiful walking areas • Discover what makes the South Downs so special from the white cliffs to the sandy beaches • Evenings in our country house where you share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 1 and 2. -

ASHINGTON ASSETS & TREASURES REPORT MAY 2019 Produced By

ASHINGTON PARISH Neighbourhood Plan ASHINGTON ASSETS & TREASURES REPORT MAY 2019 Produced by Ashington Neighbourhood Plan Steering Committee CONTENTS OVERVIEW page 2 APPENDIX 1 PLAY AREAS, OPEN SPACE, COMMUNITY & page 3 RECREATION FACILITIES APPENDIX 2 EDUCATION FACILITIES page 4 APPENDIX 3 LISTED BUILDINGS & HERITAGE ASSETS page 5 APPENDIX 4 WOODLANDS, NATURAL & GREEN SPACES, TPO’S page 14 APPENDIX 5 PONDS, WATERCOURSES & DRAINAGE DITCHES page 16 APPENDIX 6 EMPLOYMENT SPACE, BUSINESS & RETAIL page 18 APPENDIX 7 TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE including FOOTPATHS, BRIDLEWAYS & GREEN LINKS page 19 This is a ‘live’ document and may be revised, if appropriate, during the Neighbourhood Plan process. Ashington Neighbourhood Plan Assets & Treasures Report May 2019 OVERVIEW ASSETS OWNED BY ASHINGTON PARISH COUNCIL – see Appendix 1 1. Freehold property east side of London Road, Ashington. Title No WSX 29553 2. Freehold property east side of London Road, Ashington, to the south of The Mews Title No WSX 265651 3. Land east side of Ashington (Nature Trail) Title Number WSX 277205 4. Land around Church Close Title Number WSX 292639 5. Northern end of Nature Trail Title Number WSX 294226 6. Warminghurst Close Play Area. Title Number WSX 299572 7. Northern end of western tree boundary (buffer zone). Title Number WSX 299575 8. Persimmon Homes land - balancing pond area, part of western tree boundary and various pieces of verge in Covert Mead, land west of Footpath 2606 Title Number WSX 322598 9. Wimpey Homes – balancing pond area Title Number WSX223475 10. Other significant assets: 4 bus shelters, 2 village seats, 6 noticeboards, Posthorses Play Area Playground equipment, Warminghurst Close Play Area Playground equipment, Foster Lane Play Equipment, Youth Shelter ASSETS OWNED BY ASHINGTON COMMUNITY CENTRE TRUST – see Appendix 1 1. -

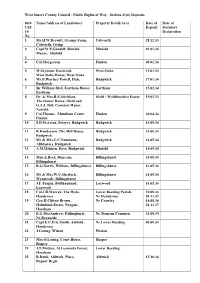

Section 31(6) Deposits 06/0 1/20 10 No. Name/Address of Landowner

West Sussex County Council - Public Rights of Way - Section 31(6) Deposits 06/0 Name/Address of Landowner Property Detail/Area Date of Date of 1/20 Deposit Statutory 10 Declaration No. 1 Mr.H.W.Drewitt, Grange Farm, Colworth 28.12.33 Colworth, Oving 2 Capt.W.P.Gandell, Slinfold Slinfold 01.01.34 Manor, Slinfold 3 4 Col.Margesson Findon 05.01.34 5 W.Seymour Eastwood, West Stoke 12.01.34 West Stoke House, West Stoke 6 Mr.B.Worlsey Powell, Hale, Rudgwick 17.01.34 Rudgwick 7 Sir William Bird, Eartham House, Eartham 15.02.34 Eartham 8 Dr. & Mrs.R.S.Aitchison, Ifield - Woldhurstlea Estate 19.02.34 The Dower House, Ifield and G.A.J. Bell, Cawston Manor, Norfolk. 9 Col.Thynne, Muntham Court, Findon 30.04.34 Findon 10 S.D.Secretan, Swayes, Rudgwick Rudgwick 14.05.34 11 R.Henderson, The Mill House, Rudgwick 14.05.34 Rudgwick 12 Mr & Mrs.C.C.Naumann, Rudgwick 14.05.34 Aliblasters, Rudgwick 13 A.M.Holman, Hyes, Rudgwick Slinfold 14.05.34 14 Miss E.Beck, Duncans, Billingshurst 14.05.34 Billingshurst 15 R.G.Norris, Wildens, Billingshurst Billingshurst 14.05.34 16 Mr & Mrs.W.U.Sherlock, Billingshurst 14.05.34 Wynstrode, Billingshurst 17 J.F.Turpin, Beldhamland, Loxwood 14.05.34 Loxwood 18 Col.J.R.Warren, The Hyde, Lower Beeding Parish, 10.08.34 Handcross Nr.Handcross 24.11.37 19 Gen.H.Clifton-Brown, Nr.Crawley 16.08.34 Holmbush Estate, Faygate, 24.11.37 Horsham 20 E.G.MacAndrew, Pallinghurst, Nr.Tismans Common 31.08.34 Nr.Baynards 21 Capt.E.C.Eric Smith, Ashfold , Nr.Lower Beeding 05.09.34 Handcross 22 J.Goring, Wiston Wiston 23 Mrs.O.Loring, Court House, Rusper Rusper 24 J.T.McGaw, St.Leonards Forest, Lower Beeding Horsham 25 R.Rank, Aldwick Place, Aldwick 15.10.34 Bognor Regis No. -

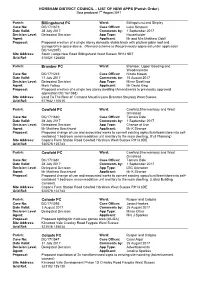

HORSHAM DISTRICT COUNCIL – LIST of NEW APPS (Parish Order) Data Produced 7Th August 2017

HORSHAM DISTRICT COUNCIL – LIST OF NEW APPS (Parish Order) Data produced 7th August 2017 Parish: Billingshurst PC Ward: Billingshurst and Shipley Case No: DC/17/1673 Case Officer: Luke Simpson Date Valid: 28 July 2017 Comments by: 1 September 2017 Decision Level: Delegated Decision App Type: Householder Agent: Applicant: Mr and Mrs Matthew Odell Proposal: Proposed erection of a single storey domestic stable block with pitched gable roof and storage/office space above. (Revised scheme to that previously approved under application DC/14/2097). Site Address: South Lodge New Road Billingshurst West Sussex RH14 9DT Grid Ref: 510021 126858 Parish: Bramber PC Ward: Bramber, Upper Beeding and Woodmancote Case No: DC/17/1245 Case Officer: Nicola Mason Date Valid: 17 July 2017 Comments by: 15 August 2017 Decision Level: Delegated Decision App Type: Minor Dwellings Agent: Mark Folkes Applicant: Mr David King Proposal: Proposed erection of a single two storey dwelling (Amendments to previously approved application DC/16/1088) Site Address: Land To The Rear of Crimond Maudlin Lane Bramber Steyning West Sussex Grid Ref: 517942 110615 Parish: Cowfold PC Ward: Cowfold,Shermanbury and West Grinstead Case No: DC/17/1680 Case Officer: Tamara Dale Date Valid: 28 July 2017 Comments by: 1 September 2017 Decision Level: Delegated Decision App Type: Change of Use Agent: Mr Matthew Brockhurst Applicant: Mr K Strange Proposal: Proposed change of use and associated works to convert existing agricultural barn/store into self- contained 1 bedroom accommodation unit