The Purple Heart: Background and Issues for Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D4 DEACCESSION LIST 2019-2020 FINAL for HLC Merged.Xlsx

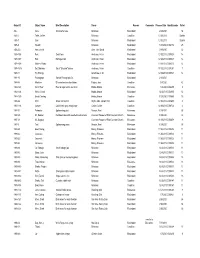

Object ID Object Name Brief Description Donor Reason Comments Process Date Box Barcode Pallet 496 Vase Ornamental vase Unknown Redundant 2/20/2020 54 1975-7 Table, Coffee Unknown Condition 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-7 Saw Unknown Redundant 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-9 Wrench Unknown Redundant 1/28/2020 C002172 25 1978-5-3 Fan, Electric Baer, John David Redundant 2/19/2020 52 1978-10-5 Fork Small form Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-7 Fork Barbeque fork Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-9 Masher, Potato Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-16 Set, Dishware Set of "Bluebird" dishes Anderson, Helen Condition 11/12/2019 C001351 7 1978-11 Pin, Rolling Grantham, C. W. Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1981-10 Phonograph Sonora Phonograph Co. Unknown Redundant 2/11/2020 1984-4-6 Medicine Dr's wooden box of antidotes Fugina, Jean Condition 2/4/2020 42 1984-12-3 Sack, Flour Flour & sugar sacks, not local Hobbs, Marian Relevance 1/2/2020 C002250 9 1984-12-8 Writer, Check Hobbs, Marian Redundant 12/3/2019 C002995 12 1984-12-9 Book, Coloring Hobbs, Marian Condition 1/23/2020 C001050 15 1985-6-2 Shirt Arrow men's shirt Wythe, Mrs. Joseph Hills Condition 12/18/2019 C003605 4 1985-11-6 Jumper Calvin Klein gray wool jumper Castro, Carrie Condition 12/18/2019 C001724 4 1987-3-2 Perimeter Opthamology tool Benson, Neal Relevance 1/29/2020 36 1987-4-5 Kit, Medical Cardboard box with assorted medical tools Covenant Women of First Covenant Church Relevance 1/29/2020 32 1987-4-8 Kit, Surgical Covenant -

Do You Know Where This

The SAR Colorguardsman National Society, Sons of the American Revolution Vol. 6 No. 3 Oct 2017 Inside This Issue From the Commander From the Vice-Commander Ad Hoc Committee Update Do you Firelock Drill positions Color Guard Commanders SAR Vigil at Mt Vernon know where Reports from the Field - 13 Societies Congress Color Guard Breakfast this is? Change of Command Ring Ritual Color Guardsman of the Year National Historic Sites Calendar Color Guard Events 2017 The SAR Colorguardsman Page 2 The purpose of this Commander’s Report Magazine is to It has been a very active two month period since the Knoxville Congress in provide July. I have had the honor of commanding the Color Guard at the Installation interesting Banquet in Knoxville, at the Commemoration of the Battle of Blue Licks in articles about the Kentucky, at the Fall Leadership Meeting in Louisville,the grave markings of Revolutionary War and Joshua Jones and George Vest, and at the Anniversary of the Battle of Kings Mountain in South Carolina. information regarding the I have also approved 11 medals - 6 Molly Pitcher Medals and 5 Silver Color activities of your chapter Guard Medals. Please review the Color Guard Handbook for the qualifica- tions for these medals as well as the National Von Steuben Medal for Sus- and/or state color guards tained Activity. The application forms for these can be found on the National website. THE SAR The following goals have been established for the National Color Guard COLORGUARDSMAN for 2017 to 2018: The SAR Colorguardsman is 1) Establish published safety protocols and procedures with respect to Color Guard conduct published four times a year and use of weaponry at events. -

Purple Heartbeat November 2019

November 2019 NATIONAL COMMANDER’S CALL Inside this issue: My fellow Patriots: As your National Commander, I am proud of each and every Patriot member of the Military Order of the Purple Heart and I salute you for your loyal and valiant service to our great nation. Veterans Day is a special day, set aside Commanders Call 1 for all Americans to reflect on the many sacrifices and the great achievements of the brave men and women who have protected and defended our freedom since the Adjutants Call 2 days of the American Revolution. For those of us who bear the scars of war, this day has special meaning and sentiment. Patriots of the Month 3-6 Unlike Memorial Day, when we honor those who made the ultimate sacrifice, this day honors the many other veterans who gave their all, but were able to return to their Chapters of the Month 7 homes and their families. At home, they continue to serve and contribute to making their communities a better place to live. I urge all Americans to pause today to pay respect those veterans in your family, your community, and other friends by thanking Activities Across the 8-12 them for their service and sacrifice. If possible, take time to visit with our sick and Order disabled veterans and assure them that they will not be forgotten. For me, Veterans Washington Post Article 13- Day is a day of reflection --it's the day that I allow my thoughts to return to Iraq and 14 pay tribute to those brave men and women with whom I served. -

MR Abbreviations

What are Morning Reports? Filed each morning by each company to higher headquarters, the company morning report provided a day-by-day record of unit location, activity, and changes in company personnel. That is, these reports were an “exception-based” accounting of the individuals whose duty status had changed from the previous day. Among the reasons for an individual being listed in this report were: transfer into the unit, promotion or demotion, killed or wounded (including a brief description of wounds), captured or missing in action, transfer to another unit, hospitalization, training, AWOL and desertion. Entries included the soldier’s rank, Army Serial Number, and other information. The morning report entries made extensive use of abbreviations, including the following: A Army gr grade A&D Admission & Disposition (hospital) GSW Gun-Shot Wound Abv Above hosp hospital AGF Allied Ground Forces jd joined APO Army Post Office LD Line of Duty aptd appointed LIA Lightly Injured in Action ar arrest Lv Leave of Duty AR Army Regulation LWA Lightly Injured in Action arr arrived MCO Main Civilian Occupation ASF Army Service Forces MOS Military Occupational Specialty asgd assigned NLD Not in line of duty asgmt assignment NYPE New York Port of Embarkation atchd attached par paragraph AW Articles of War Pers personnel AWOL Absent without Leave Plat or Pltn platoon Bn battalion PM Postmaster Clr Sta Clearing Station qrs quarters CM Court Martial RD Replacement Depot Conf confined Regt Regiment DB Daily Bulletin reld relieved DoP Detachment of Patients -

2020-2021 Veteran Services Guide

2020-2021 Veteran Services Guide July 2021 Welcome to North Carolina Wesleyan College and the Office of Veteran Services. This Guide was created so that military-connected students could find all the information specific to them in one place. We update yearly, so if there is information you would like to see that we have left out, please email [email protected] and give us your input. The Veterans Services Office is located next to the Business Office in the Pearsall Classroom Building, Room 192-B at the Main Campus in Rocky Mount. Please stop by and say hello. Thank you to you and your family for your service to our Country. We look forward to serving you! Very Respectfully, Laura Estes Brown Associate Dean of Veteran Services ROTC Adviser VA School Certifying Official 2 Revised 29 June 2021 Table of Contents Getting Started Checklist .............................................................................................................4 VA Benefits Overview ......................................................................................................................................................5 Benefits At-A-Glance ..................................................................................................................................7 Frequently Asked Questions ....................................................................................................................7 Resources Military Deployment Policy .................................................................................................................. -

How Huge U. S. Navy Guns Mounted on Railway Cars

PalaLIJHEDDAILr under order of THE PREXIDENT of THE UNITED STATES by COMMITTEE on PUBLIC INFORMATION GEORGE CREEL, ChairmaA * * COMPLETE Record of U. S. GOVERNMENT Activities VoL. 2 WASHINGTON, SATURDAY, OCTOBER 26, 1918. No. 447 REPORT AGAINST WAGE INCREASE TWELVE FOE AIRCRAFT DOWNED HOW HUGE U.S. NAVY GUNS FOR BITUMINOUS COAL MINERS BY II.S. FLYERS IN13 DAYS MOUNTED ON RAILWAY CARS MADE TO FUEL ADMINISTRATOR The War Department authorizes the . following: ARE NOW HURLING SHELLS HELD NOT WARRANTED AT PRESENT Eleven enemy airplanes and one hos- tile balloon were brought down by Ameri- can aviators brigaded -lth the British FAR BEHIND GERMAN LINES "Uncalled for as Part of the Plan during the period from September 9 to September 22, inclusive, and five Ameri- of Stabilization" Says Telegram can aviators were awarded the British BAN OFSECRECYLIFTED Sent President Hayes of United distinguished flying cross, according to the latest Royal Flying Corps commu- BYSECRETARYDANIELS Mine Workers of America. niques just received here. Received Special Mention. Special Cars and Locomo- Bituminous mine workers under agree- ment with the Government to continue Special mention was made as follows: tives Were Built in This " Lieut. G. A. Vaughn, while on offen- operations at the existing scale until the Country - Largest Can- end of the war or for a period of two sive patrol. was engaged by about 15 en- years were notified on Friday by United emy airplanes, one of which, which was at- non Ever Placed on Mobile States Fuel Administrator Harry A. Gar- tacking a flight of our machines he dived field that existing information does not on and shot down in flames. -

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Updated July 29, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32492 American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Summary This report provides U.S. war casualty statistics. It includes data tables containing the number of casualties among American military personnel who served in principal wars and combat operations from 1775 to the present. It also includes data on those wounded in action and information such as race and ethnicity, gender, branch of service, and cause of death. The tables are compiled from various Department of Defense (DOD) sources. Wars covered include the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam Conflict, and the Persian Gulf War. Military operations covered include the Iranian Hostage Rescue Mission; Lebanon Peacekeeping; Urgent Fury in Grenada; Just Cause in Panama; Desert Shield and Desert Storm; Restore Hope in Somalia; Uphold Democracy in Haiti; Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF); Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF); Operation New Dawn (OND); Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR); and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). Starting with the Korean War and the more recent conflicts, this report includes additional detailed information on types of casualties and, when available, demographics. It also cites a number of resources for further information, including sources of historical statistics on active duty military deaths, published lists of military personnel killed in combat actions, data on demographic indicators among U.S. military personnel, related websites, and relevant CRS reports. Congressional Research Service American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

Guidebook: American Revolution

Guidebook: American Revolution UPPER HUDSON Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site http://nysparks.state.ny.us/sites/info.asp?siteId=3 5181 Route 67 Hoosick Falls, NY 12090 Hours: May-Labor Day, daily 10 AM-7 PM Labor Day-Veterans Day weekends only, 10 AM-7 PM Memorial Day- Columbus Day, 1-4 p.m on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday Phone: (518) 279-1155 (Special Collections of Bailey/Howe Library at Uni Historical Description: Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site is the location of a Revolutionary War battle between the British forces of Colonel Friedrich Baum and Lieutenant Colonel Henrick von Breymann—800 Brunswickers, Canadians, Tories, British regulars, and Native Americans--against American militiamen from Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire under Brigadier General John Stark (1,500 men) and Colonel Seth Warner (330 men). This battle was fought on August 16, 1777, in a British effort to capture American storehouses in Bennington to restock their depleting provisions. Baum had entrenched his men at the bridge across the Walloomsac River, Dragoon Redoubt, and Tory Fort, which Stark successfully attacked. Colonel Warner's Vermont militia arrived in time to assist Stark's reconstituted force in repelling Breymann's relief column of some 600 men. The British forces had underestimated the strength of their enemy and failed to get the supplies they had sought, weakening General John Burgoyne's army at Saratoga. Baum and over 200 men died and 700 men surrendered. The Americans lost 30 killed and forty wounded The Site: Hessian Hill offers picturesque views and interpretative signs about the battle. Directions: Take Route 7 east to Route 22, then take Route 22 north to Route 67. -

Purple Heartbeat October 2019 Approved

October 2019 NATIONAL COMMANDER’S CALL Inside this issue: Patriots, Associates, Auxiliary, and Friends of MOPH: Commanders Call 1 It is with a great sense of personal loss and sadness that I Adjutants Call 2 inform you that the National Viola Chairman, Robert J. "Bob" Connor, passed away on October 3, 2019 and joined the ranks of America’s Membership 3 great fallen heroes. Patriot Connor was appointed to the position of National Viola Chairman in 2012 by Past National Commander Bruce Chapters on the Move 4 McKenty. In addition to serving as both Adjutant and Finance Officer for Chapter 268, he also served as Adjutant for the Department of Chapters of the Week 5 Minnesota for several years.. In 2011, Patriot Connor served as Chairman of the MOPH National Convention. Bob is a Vietnam Patriots of the Week 6-10 Veteran and served on active duty with the US Army from 1967-1969. He is a1967 graduate of St. John’s University (MN). Bob was born in Purple Heart Veteran to 11 receive ‘rolling tribute’ St. Paul, Minnesota where he continued to reside with his wife Nan truck and Children. Additional information on memorial services and burial Postal Service to start 12 will be provided when made available. selling new PH stamps on Oct. 4 Legacy Program 13 Yours In Patriotism, Felix Garcia III MOPH Calendar 14 Know Your National 15 Felix Garcia III Officers National Commander MOPH Region Commanders 16 October 2019 NATIONAL ADJUTANT’S CALL Dear Patriots, Since arriving at the National HQ in July, we have been able to get 95% of all past bills paid and all contracts restructured. -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

Cheers! 'Stuttgarter Weindorf'

MORE ONLINE: Visit StuttgartCitizen.com and sign up for the daily email for more timely announcements NEWS FEATURE HEALTH BEAT FORCES UNITE ARE YOU PREPARED? New science-based techno- U.S. Marine Forces Europe and How to be ready in the event logy to reach and sustain a Africa unite with a new commander. — PAGE 2 of an emergency. — PAGES 12-13 healthy weight. — PAGE 10 FLAKKASERNE REMEMBERED Ludwigsburg to honor the service of U.S. Armed Forces with plaque unveiling and free entrance to Garrison Museum and Ludwigsburg Palace Sept. 13. — PAGE 3 Thursday, September 3, 2015 Sustaining & Supporting the Stuttgart U.S. Military Community Garrison Website: www.stuttgart.army.mil Facebook: facebook.com/USAGarrisonStuttgart stuttgartcitizen.com Cheers! ‘Stuttgarter Weindorf’ Only a few days left to enjoy a swell time at local wine fest. — Page 5 Photos courtesy of Regio Stuttgart Marketing-und Tourismus GmbH Tourismus Stuttgart Marketing-und Photos courtesy of Regio NEWS ANNOUNCEMENTS GOING GREEN ASK A JAG 709th Military Police Battalion Löwen Award Community news updates including closures Federal Procurement programs require purchases What newcomers need to know about fi ling presented to outstanding FRG leader of 554th and service changes, plus fun activities of 'green' products and services. claims for household goods, vehicles and Military Police Company. — PAGE 8 coming up at the garrison. — PAGE 6-7 — PAGE 4 more. — PAGE 4 Page 2 NEWS The Citizen, September 3, 2015 is newspaper is an authorized publication for members of the Department of Defense. Contents of e Citizen are not necessarily the o cial views of, or Marines across continents unite endorsed by, the U.S. -

Purple Heart

Purple Heart MAGAZINE January/February 2019 © Purple Heart Magazine ISSN: 0279-0653 January/February 2019 2IÀFLDO3XEOLFDWLRQRIWKH MILITARY ORDER OF THE PURPLE HEART OF THE U.S.A., Inc. Chartered by Act of Congress RAELYNN MCAFEE, EDITOR, PURPLE HEART MAGAZINE • LOLLO SCHNITTGER NYLEN, DESIGN & PRODUCTION • JEFF TAMARKIN, COPY EDITOR MOPH National Headquarters [email protected] ADDRESS changes, DEATH of a Member & SUBSCRIPTIONS %%DFNOLFN5RDG6SULQJÀHOG9$9RLFH )D[ 6XEVFULSWLRQUDWHVIRUQRQPHPEHUVLQWKH8QLWHG6WDWHVDQGLWVSRVVHVVLRQVDUHSHU\HDU LVVXHV RUSHUVLQJOHLVVXHLQRWKHUFRXQWULHVSHU\HDU which includes postage. NEWS, PHOTOS, and EDITORIALS to: National Editor [email protected] RaeLynn McAfee, 2037 Warner Drive,Chuluota, FL 32766 Magazine COMMENTS to: Publications Committee Chairman [email protected] 1LFN0F,QWRVK&KDSHO/DQH1HZ$OEDQ\,1 & COPYRIGHT 2019 by Military Order of the Purple Heart, Inc. All rights reserved. 3XUSOH+HDUW ,661 LVSXEOLVKHGELPRQWKO\E\0LOLWDU\2UGHURIWKH3XUSOH+HDUWRIWKH86$,QF%%DFNOLFN5G6SULQJÀHOG9$ 3HULRGLFDOVSRVWDJHSDLGDW6SULQJÀHOG9$DQGDWDGGLWLRQDOPDLOLQJRIÀFHV POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Purple Heart Magazine,%%DFNOLFN5RDG6SULQJÀHOG9$ THE HOMECOMING THEY DESERVE... THE SUPPORT THEY NEED. Donate Today! Purple Heart Service Foundation Call us to donate: 888-414-4483 • Or go online: www.purpleheartcars.org HELPING OUR COMBAT WOUNDED WARRIORS & THEIR FAMILIES 2 PURPLE HEART MAGAZINE January/February 2019 Purple Heart 4(.(A05, 6ɉJPHS7\ISPJH[PVUVM[OL4PSP[HY`6YKLYVM[OL7\YWSL/LHY[VM[OL<:(0UJ TABLEOFCONTENTS