Survey on Issue Analysis of Food Value Chain in the Philippines Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Climate Change on the World's Oceans

3rd International Symposium Effects of Climate Change on the World’s Oceans March 21–27, 2015 Santos, Brazil Table of Contents Welcome � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � v Organizers and Sponsors � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �vi Notes for Guidance � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �ix Symposium Timetable � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � x List of Sessions and Workshops � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � xiii Floor Plans � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �xiv Detailed Schedules � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1 Abstracts - Oral Presentations Keynote � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �77 Plenary Talks � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �79 Theme Session S1 Role of advection and mixing in -

Updated Directory of City /Municipal Civil Registrars Province of Antique As of January 3, 2020

Updated Directory of City /Municipal Civil Registrars Province of Antique As of January 3, 2020 NAME Appointment Telephone Number City/Municipality Sex E-mail Address Address of LCRO Remarks Last First Middle Status Landline Mobile Fax [email protected] ANINI-Y PADOHINOG CLARIBEL CLARITO F PERMANENT 09067500306/ 09171266474 ANINI-Y, ANTIQUE [email protected] BARBAZA ALABADO JACOBINA REMO F PERMANENT 09175521507 [email protected] BARBAZA,ANTIQUE BELISON ABARIENTOS MERCY LAMPREA F PERMANENT 09162430477 [email protected] BELISON,ANTIQUE BUGASONG CRESPO KARINA MAE PEDIANGCO F PERMANENT 09352748755 [email protected] BUGASONG, ANTIQUE CALUYA PAGAYONAN NINI YAP F PERMANENT 09122817444/09171003404 [email protected] CALUYA, ANTIQUE CULASI GUAMEN RONALD REY REMEGIO M PERMANENT (036)277-8622 09193543534/ 09778830071 (036)277-8003 [email protected] CULASI, ANTIQUE T. FORNIER (DAO) SARCON DELIA YSULAT F PERMANENT 09175617419/09286349619 [email protected] T. FORNIER, ANTIQUE HAMTIC MABAQUIAO RAMONA ZALDIVAR F OIC-MCR (036) 641-5335 09173524504 HAMTIC, ANTIQUE [email protected]/ LAUA-AN PON-AN GINA LAGRIMOSA F PERMANENT 09088910468/09171407920 LAUA-AN, ANTIQUE [email protected] LIBERTAD PALMARES ELMA CASTILLO F PERMANENT (036) 278-1675 09276875529/09192292222 [email protected] LIBERTAD, ANTIQUE PANDAN EBON DONNA RIOMALOS F PERMANENT (036) 278-9567 09496149243 [email protected] PANDAN, ANTIQUE PATNONGON DUNGGANON VICTORIA ESTARIS F PERMANENT 09369721019 [email protected] PATNONGON,ANTIQUE SAN -

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines November 2005 Republika ng Pilipinas PAMBANSANG LUPON SA UGNAYANG PANG-ESTADISTIKA (NATIONAL STATISTICAL COORDINATION BOARD) http://www.nscb.gov.ph in cooperation with The WORLD BANK Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines FOREWORD This report is part of the output of the Poverty Mapping Project implemented by the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) with funding assistance from the World Bank ASEM Trust Fund. The methodology employed in the project combined the 2000 Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES), 2000 Labor Force Survey (LFS) and 2000 Census of Population and Housing (CPH) to estimate poverty incidence, poverty gap, and poverty severity for the provincial and municipal levels. We acknowledge with thanks the valuable assistance provided by the Project Consultants, Dr. Stephen Haslett and Dr. Geoffrey Jones of the Statistics Research and Consulting Centre, Massey University, New Zealand. Ms. Caridad Araujo, for the assistance in the preliminary preparations for the project; and Dr. Peter Lanjouw of the World Bank for the continued support. The Project Consultants prepared Chapters 1 to 8 of the report with Mr. Joseph M. Addawe, Rey Angelo Millendez, and Amando Patio, Jr. of the NSCB Poverty Team, assisting in the data preparation and modeling. Chapters 9 to 11 were prepared mainly by the NSCB Project Staff after conducting validation workshops in selected provinces of the country and the project’s national dissemination forum. It is hoped that the results of this project will help local communities and policy makers in the formulation of appropriate programs and improvements in the targeting schemes aimed at reducing poverty. -

Ensemble Forecast Experiment for Typhoon

Ensemble Forecast Experiment for Typhoon Quantitatively Precipitation in Taiwan Ling-Feng Hsiao1, Delia Yen-Chu Chen1, Ming-Jen Yang1, 2, Chin-Cheng Tsai1, Chieh-Ju Wang1, Lung-Yao Chang1, 3, Hung-Chi Kuo1, 3, Lei Feng1, Cheng-Shang Lee1, 3 1Taiwan Typhoon and Flood Research Institute, NARL, Taipei 2Dept. of Atmospheric Sciences, National Central University, Chung-Li 3Dept. of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University, Taipei ABSTRACT The continuous torrential rain associated with a typhoon often caused flood, landslide or debris flow, leading to serious damages to Taiwan. Therefore the quantitative precipitation forecast (QPF) during typhoon period is highly needed for disaster preparedness and emergency evacuation operation in Taiwan. Therefore, Taiwan Typhoon and Flood Research Institute (TTFRI) started the typhoon quantitative precipitation forecast ensemble forecast experiment in 2010. The ensemble QPF experiment included 20 members. The ensemble members include various models (ARW-WRF, MM5 and CreSS models) and consider different setups in the model initial perturbations, data assimilation processes and model physics. Results show that the ensemble mean provides valuable information on typhoon track forecast and quantitative precipitation forecasts around Taiwan. For example, the ensemble mean track captured the sharp northward turning when Typhoon Megi (2010) moved westward to the South China Sea. The model rainfall also continued showing that the total rainfall at the northeastern Taiwan would exceed 1,000 mm, before the heavy rainfall occurred. Track forecasts for 21 typhoons in 2011 showed that the ensemble forecast has a comparable skill to those of operational centers and has better performance than a deterministic prediction. With an accurate track forecast for Typhoon Nanmadol, the ability for the model to predict rainfall distribution is significantly improved. -

Cagayan Riverine Zone Development Framework Plan 2005—2030

Cagayan Riverine Zone Development Framework Plan 2005—2030 Regional Development Council 02 Tuguegarao City Message The adoption of the Cagayan Riverine Zone Development Framework Plan (CRZDFP) 2005-2030, is a step closer to our desire to harmonize and sustainably maximize the multiple uses of the Cagayan River as identified in the Regional Physical Framework Plan (RPFP) 2005-2030. A greater challenge is the implementation of the document which requires a deeper commitment in the preservation of the integrity of our environment while allowing the development of the River and its environs. The formulation of the document involved the wide participation of concerned agencies and with extensive consultation the local government units and the civil society, prior to its adoption and approval by the Regional Development Council. The inputs and proposals from the consultations have enriched this document as our convergence framework for the sustainable development of the Cagayan Riverine Zone. The document will provide the policy framework to synchronize efforts in addressing issues and problems to accelerate the sustainable development in the Riverine Zone and realize its full development potential. The Plan should also provide the overall direction for programs and projects in the Development Plans of the Provinces, Cities and Municipalities in the region. Let us therefore, purposively use this Plan to guide the utilization and management of water and land resources along the Cagayan River. I appreciate the importance of crafting a good plan and give higher degree of credence to ensuring its successful implementation. This is the greatest challenge for the Local Government Units and to other stakeholders of the Cagayan River’s development. -

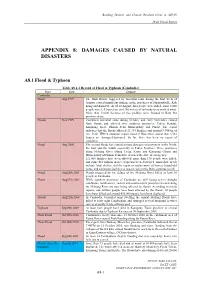

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Cepf Final Project Completion Report

CEPF FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT I. BASIC DATA Organization Legal Name: Cagayan Valley Partners in People Development Project Title (as stated in the grant agreement): Design and Management of the Northeastern Cagayan Conservation Corridor Implementation Partners for this Project: Project Dates (as stated in the grant agreement): December 1, 2004 – June 30, 2007 Date of Report (month/year): August 2007 II. OPENING REMARKS Provide any opening remarks that may assist in the review of this report. Civil society -non-government organizations and people’s organizations, together with the academe and the church- have long been in the forefront of environmental protection in the Cagayan Valley region since the 1990s. They were and still are very active in the multi-sectoral forest protection committee and community-based forest resource management (CBFM) activities. A shift towards a conservation orientation came as a natural consequence of the Rio Summit and in view of the observation that biodiversity conservation was a neglected component of CBFM. Aside from this, there began to be implemented in region 02 biodiversity conservation projects under the CPPAP- GEF, Dutch assisted conservation and development project all in Isabela and the German assisted CBFM and Conservation project in the province of Quirino. Alongside with this was the push for the corridor approach. The CEPF assisted project is a conservation initiative that has come just at the right time when there was an upswing of interest in Cagayan in biodiversity conservation and environment protection. It came as a conservation felt need for the province of Cagayan in view of the successful pro-active actions in the neighboring province of Isabela which led to the establishment of the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park. -

1. Preliminaries A) Invocation

1 2 3 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL AND BOARD OF DIRECTORS 4 Development Year 2011-2013 5 4th Regular Meeting 6 Golden Pine Hotel 7 Corner Cariño and Yandoc Streets, Baguio City 8 9 1. Preliminaries 10 a) Invocation - Bro Leonardo Cairo 11 b) National Anthem - Sis Rosalyn Bañagale 12 c) Vision-Mission Statement - Bro Leonardo Cairo 13 d) Scout Oath and Law - Bro Ray Robin Abache 14 15 2. Call to Order: 16 17 National President Mike Taha called the 4th Regular National Executive 18 Council Meeting to order at 10:01 AM at Grand Ball room, Golden Pine Hotel, 19 Baguio City. 20 21 On the same manner, BOD Chairman Luis Paredes called the 4th Regular 22 Board of Directors Meeting to order at 10:02 AM at Grand Ball room, Golden 23 Pine Hotel, Baguio City. 24 25 BOD Chairman Luis Paredes asked the NED in doing the roll call for the 26 Board of Directors Members. 27 28 3. Roll Call / Determination of Quorum 29 30 NED Reinald Relova did the roll call for the Board of Directors. 31 32 Present were: 33 BOD Chairman Luis Paredes 34 Director for Alumni Wenefredo Abordo 35 Director for Fraternity Ray Robin Abache 36 National President Mamintal Taha 37 NCAR Regional Representative Ariel Darilag 38 NLAR Regional Representative Marcelino Ferry 39 SLAR Regional Representative Rosalyn M. Banagale 40 NVAR Regional Representative Jimmy Patino APPROVED 4TH NEC & BOD MINUTES FOR DY JULY 1, 2013-JUNE 30, 2015 Page 1 of 107 41 NMAR Regional Representative Eric Cabalida 42 SMAR Regional Representative Gerardo Erasmo 43 ARNA Permanent Representative represented by Placido Fernandez 44 ARAP Permanent Representative Roberto Fajardo 45 ARE Permanent Representative Alvina Juanitez 46 National Executive Director Reinald Relova 47 48 Absent were: 49 BOD Vice Chairman Israel Ricardo Somera 50 Director for Sorority Jessica Moldez 51 SVAR Regional Representative Rodolfo Brasset Espiritu 52 ARME Permanent Representative Carina Yago 53 54 BOD Chairman Luis Paredes asked the NED Reinald Relova if there is a 55 quorum for the Board of Directors. -

Scale and Spatial Distribution Assessment of Rainfall-Induced Landslides in a Catchment with Mountain Roads

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 18, 687–708, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-18-687-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Scale and spatial distribution assessment of rainfall-induced landslides in a catchment with mountain roads Chih-Ming Tseng1, Yie-Ruey Chen1, and Szu-Mi Wu2 1Department of Land Management and Development, Chang Jung Christian University, Tainan, 71101, Taiwan (ROC) 2Chen-Du Construction Limited, Taoyuan, 33059, Taiwan (ROC) Correspondence: Chih-Ming Tseng ([email protected]) Received: 14 July 2017 – Discussion started: 4 October 2017 Revised: 27 December 2017 – Accepted: 22 January 2018 – Published: 2 March 2018 Abstract. This study focused on landslides in a catchment Landslide susceptibility can be evaluated by analysing the with mountain roads that were caused by Nanmadol (2011) relationships between landslides and various factors that are and Kong-rey (2013) typhoons. Image interpretation tech- responsible for the occurrence of landslides (Brabb, 1984; niques were employed to for satellite images captured before Guzzetti et al., 1999, 2005). In general, the factors that af- and after the typhoons to derive the surface changes. A mul- fect landslides include predisposing factors (e.g. geology, to- tivariate hazard evaluation method was adopted to establish pography, and hydrology) and triggering factors (e.g. rainfall, a landslide susceptibility assessment model. The evaluation earthquakes, and anthropogenic factors) (Chen et al., 2013a, of landslide locations and relationship between landslide and b; Chue et al., 2015). Geological factors include lithological predisposing factors is preparatory for assessing and map- factors, structural conditions, and soil thickness; topograph- ping landslide susceptibility. -

The Effect of Warm Water and Its Weak Negative Feedback on the Rapid Intensification of Typhoon Hato (2017)

Vol.26 No.4 JOURNAL OF TROPICAL METEOROLOGY Dec 2020 Article ID: 1006-8775(2020) 04-0402-15 The Effect of Warm Water and Its Weak Negative Feedback on the Rapid Intensification of Typhoon Hato (2017) HUO Zi-mo (霍子墨), DUAN Yi-hong (端义宏), LIU Xin (刘 欣) (State Key Laboratory of Severe Weather, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing 100081 China) Abstract: Typhoon Hato (2017) went through a rapid intensification (RI) process before making landfall in Zhuhai, Guangdong Province, as the observational data shows. Within 24 hours, its minimum sea level pressure deepened by 35hPa and its maximum sustained wind speed increased by 20m s-1. According to satellite observations, Hato encountered a large area of warm water and two warm core rings before the RI process, and the average sea surface temperature cooling (SSTC) induced by Hato was only around 0.73℃. Air-sea coupled simulations were implemented to investigate the specific impact of the warm water on its RI process. The results showed that the warm water played an important role by facilitating the RI process by around 20%. Sea surface temperature budget analysis showed that the SSTC induced by mixing mechanism was not obvious due to the warm water. Besides, the cold advection hardly caused any SSTC, either. Therefore, the SSTC induced by Hato was much weaker compared with that in general cases. The negative feedback between ocean and Hato was restrained and abundant heat and moisture were sufficiently supplied to Hato. The warm water helped heat flux increase by around 20%, too. Therefore, the warm water influenced the structure and the intensity of Hato. -

Updated Directory of City /Municipal Civil Registrars Province of Antique As of January 7, 2016

Updated Directory of City /Municipal Civil Registrars Province of Antique As of January 7, 2016 NAME Appointment Telephone Number City/Municipality Sex E-mail Address Address of LCRO Last First Middle Status Landline Mobile Fax ANINI-Y PADOHINOG CLARIBEL CLARITO F PERMANENT 09154138960/09086760395 [email protected] ANINI-Y, ANTIQUE BARBAZA ALABADO JACOBINA REMO F PERMANENT 09175521507 [email protected] BARBAZA,ANTIQUE BELISON ABARIENTOS MERCY LAMPREA F PERMANENT 09162430477/09475634977 [email protected] BELISON,ANTIQUE BUGASONG CRESPO KARINA MAE PEDIANGCO F PERMANENT 09272141243/09352748755 [email protected], ANTIQUE CALUYA PAGAYONAN NINI YAP F PERMANENT 09177746530 [email protected] CALUYA, ANTIQUE CULASI GUAMEN RONALD REY REMEGIO M PERMANENT (036)277-86-22 09193543534 (036)277-80-03 [email protected] CULASI, ANTIQUE T. FORNIER (DAO) SARCON DELIA YSULAT F PERMANENT 09179704355/09286349619 [email protected] T. FORNIER, ANTIQUE HAMTIC ELIZALDE JOSELINDA OLAGUER F PERMANENT 09173050847/09175621587 [email protected] HAMTIC, ANTIQUE LAUA-AN PON-AN GINA LAGRIMOSA F PERMANENT 09173103479/09088910468 [email protected] LAUA-AN, ANTIQUE LIBERTAD PALMARES ELMA CASTILLO F PERMANENT (036)278-1675 09192292222 036-278-1510 [email protected] LIBERTAD, ANTIQUE PANDAN EBON DONNA RIOMALOS F PERMANENT 09496149243/09460668080 PANDAN, ANTIQUE PATNONGON DUNGGANON VICTORIA ESTARIS F PERMANENT 09369721019 [email protected] PATNONGON,ANTIQUE SAN JOSE VEGO INOCENCIO JR SALAZAR M PERMANENT (036)540-7832 -

Health Action in Crises PHILIPPINES FLOODS

Health Action in Crises PHILIPPINES FLOODS Situation 2 December 2004 - Tropical Depression "Winnie" has triggered massive floods in northern and central Philippines. Some 400 persons are reported dead, with many people still unaccounted for. An estimated 240,000 persons have been directly affected (government figures). The most affected provinces include Isabela (Region II); Bulacan, Nueva Ecija and Aurora (Region III); Quezon and Rizal (Region IV) and Camarines Sur (Region V). Efforts are focused on search and rescue activities. The procurement and distribution of relief items are also underway. The National Disaster Coordination Council (NDCC) is charged with heading the response, in conjunction with the Defense Department. The NDCC is supported by the UN in-country team. Possible needs in the health sector A comprehensive impact assessment has not yet been undertaken. However, it can be anticipated that the following issues may be of concern: ¾ Damage to health facilities and equipment, as well as disrupted medical supply systems. ¾ Outages in electricity endanger the cold chain. ¾ Relocation of people may result in an overburden of functional primary and referral health services. ¾ Floods and landslides could lead to the disruption of water distribution systems and the loss/contamination of water supplies. In flood situations, the lack of safe drinking water supplies and adequate sanitation, combined with population displacement, heightens the risk of outbreaks of water- and vector-borne diseases. ¾ Shortage of supplies and staff for mass casualty management could occur. WHO immediate actions WHO has mobilized US$ 20,000 to support the assessment of urgent health needs. Medical kits are on standby and are ready to be shipped should they be needed.