RED Production and the Cultural Politics of Place1 Andrew Spicer My Work for Channel 4 Is Driven Not by Ad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOMINATIONS with WINNERS *HIGHLIGHTED 10 May 2015 FELLOWSHIP JON SNOW

NOMINATIONS WITH WINNERS *HIGHLIGHTED 10 May 2015 FELLOWSHIP JON SNOW SPECIAL AWARD JEFF POPE LEADING ACTOR BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Sherlock – BBC One TOBY JONES Marvellous – BBC Two JAMES NESBITT The Missing – BBC One *JASON WATKINS The Lost Honour of Christopher Jefferies - ITV LEADING ACTRESS *GEORGINA CAMPBELL Murdered by My Boyfriend – BBC Three KEELEY HAWES Line of Duty – BBC Two SARAH LANCASHIRE Happy Valley – BBC One SHERIDAN SMITH Cilla - ITV SUPPORTING ACTOR ADEEL AKHTAR Utopia – Channel 4 JAMES NORTON Happy Valley – BBC One *STEPHEN REA The Honourable Woman – BBC Two KEN STOTT The Missing – BBC One SUPPORTING ACTRESS *GEMMA JONES Marvellous – BBC Two VICKY MCCLURE Line of Duty – BBC Two AMANDA REDMAN Tommy Cooper: Not like That, Like This - ITV CHARLOTTE SPENCER Glue – E4 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE *ANT AND DEC Ant and Dec’s Saturday Night Takeaway – ITV LEIGH FRANCIS Celebrity Juice – ITV2 GRAHAM NORTON The Graham Norton Show – BBC One CLAUDIA WINKLEMAN Strictly Come Dancing – BBC One FEMALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME OLIVIA COLMAN Rev. – BBC Two TAMSIN GREIG Episodes – BBC Two *JESSICA HYNES W1A – BBC Two CATHERINE TATE Catherine Tate’s Nan – BBC One MALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME *MATT BERRY Toast of London – Channel 4 HUGH BONNEVILLE W1A – BBC Two TOM HOLLANDER Rev. – BBC Two BRENDAN O’CARROLL Mrs Brown’s Boys – Christmas Special – BBC One SINGLE DRAMA A POET IN NEW YORK Aisling Walsh, Ruth Caleb, Andrew Davies, Griff Rhys Jones - Modern Television/BBC Two COMMON Jimmy McGovern, David Blair, Colin McKeown, Donna -

Managing the BBC's Estate

Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media & Sport by Command of Her Majesty January 2015 © BBC 2015 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. BBC Trust response to the National Audit Office value for money study: Managing the BBC’s estate This year the Executive has developed a BBC Trust response new strategy which has been reviewed by As governing body of the BBC, the Trust is the Trust. In the short term, the Executive responsible for ensuring that the licence fee is focused on delivering the disposal of is spent efficiently and effectively. One of the Media Village in west London and associated ways we do this is by receiving and acting staff moves including plans to relocate staff upon value for money reports from the NAO. to surplus space in Birmingham, Salford, This report, which has focused on the BBC’s Bristol and Caversham. This disposal will management of its estate, has found that the reduce vacant space to just 2.6 per cent and BBC has made good progress in rationalising significantly reduce costs. -

FOTV-Report-Online-SP.Pdf

A FUTURE FOR PUBLIC SERVICE TELEVISION: CONTENT AND PLATFORMS IN A DIGITAL WORLD A report on the future of public service television in the UK in the 21st century www.futureoftv.org.uk 1 2 Contents Foreword by David Puttnam 4 Introduction 7 Chapter 1: Television and public service 14 Chapter 2: Principles of public service for the 21st century 28 Chapter 3: Television in a rapidly changing world: channels, content and platforms 38 Chapter 4: The BBC 50 Chapter 5: Channel 4 66 Chapter 6: ITV and Channel 5 78 Chapter 7: New sources of public service content 90 Chapter 8: TV: a diverse environment? 102 Chapter 9: Nations and regions 114 Chapter 10: Content diversity 128 Chapter 11: Talent development and training 144 Chapter 12: Conclusion and recommendations 152 Appendix 1: Sir David Normington’s proposals for appointing the BBC board 160 Appendix 2: BAFTA members’ survey 164 Appendix 3: Onora O’Neill, ‘Public service broadcasting, public value and public goods’ 172 Appendix 4: Inquiry events 176 Acknowledgements 179 3 Foreword by Lord Puttnam Public service broadcasting is a noble 20th If only the same could be said of much of century concept. Sitting down to write this our national popular press. Our democracy preface just a few days before the most suffers a distorting effect in the form of significant British political event of my mendacious axe-grinding on the part of most lifetime, with no idea of what the result might of the tabloid newspapers. In his brilliant be, there is every temptation to escape into new book, Enough Said, the former director neutral generalities. -

London Calling: BBC External Services, Whitehall and the Cold War 1944- 57

London calling: BBC external services, Whitehall and the cold war 1944- 57. Webb, Alban The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1577 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] LONDON CALLING: SSC EXTERNAL SERVICES, WHITEHALL AND THE COLD WAR, 1944-57 ALBAN WEBB Queen Mary College, University of London A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) 1 Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: '~"\ ~~Ue6b Alban Webb Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: Alban Webb ABSTRACT The Second World War had radically changed the focus of the BBC's overseas operation from providing an imperial service in English only, to that of a global broadcaster speaking to the world in over forty different languages. The end of that conflict saw the BBC's External Services, as they became known, re-engineered for a world at peace, but it was not long before splits in the international community caused the postwar geopolitical landscape to shift, plunging the world into a cold war. At the British government's insistence a re-calibration of the External Services' broadcasting remit was undertaken, particularly in its broadcasts to Central and Eastern Europe, to adapt its output to this new and emerging world order. -

The Speakers and Chairs 2016

WEDNESDAY 24 FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE 09:30-09:45 10:00-11:00 BREAK BREAK 11:45-12:45 BREAK 13:45-14:45 BREAK 15:30-16:30 BREAK 18:00-19:00 19:00-21:30 20:50-21:45 THE SPEAKERS AND CHAIRS 2016 SA The Rolling BT “Feed The 11:00-11:20 11:00-11:45 P Edinburgh 12:45-13:45 P Meet the 14:45-15:30 P Meet the MK London 2012 16:30-17:00 The MacTaggart ITV Opening Night FH People Hills Chorus Beast” Welcome F Revealed: The T Breakout Does… T Breakout Controller: T Creative Diversity Controller: to Rio 2016: SA Margaritas Lecture: Drinks Reception Just Do Nothing Joanna Abeyie David Brindley Craig Doyle Sara Geater Louise Holmes Alison Kirkham Antony Mayfield Craig Orr Peter Salmon Alan Tyler Breakfast Hottest Trends session: An App Taskmaster session: Charlotte Moore, Network Drinks: Jay Hunt, The Superhumans’ and music Shane Smith The Balmoral screening with Thursday 14.20 - 14.55 Wednesday 15:30-16:30 Thursday 15:00-16:00 Thursday 11:00-11:30 Thursday 09:45-10:45 Wednesday 15:30-16:30 Wednesday 12:50-13:40 Thursday 09:45-10:45 Thursday 10:45-11:30 Wednesday 11:45-12:45 The Tinto The Moorfoot/Kilsyth The Fintry The Tinto The Sidlaw The Fintry The Tinto The Sidlaw The Networking Lounge 10:00-11:30 in TV Formats for Success: Why Branded Content BBC A Little Less Channel 4 Struggle For The Edinburgh Hotel talent Q&A The Pentland Digital is Key in – Big Cash but Conversation, Equality Playhouse F Have I Got F Winning in F Confessions of FH Porridge Adam Abramson Dan Brooke Christiana Ebohon-Green Sam Glynne Alex Horne Thursday 11:30-12:30 Anne Mensah Cathy -

E-Petition Session: TV Licensing, HC 1233

Petitions Committee Oral evidence: E-petition session: TV Licensing, HC 1233 Monday 1 March 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 1 March 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Catherine McKinnell (Chair); Tonia Antoniazzi; Jonathan Gullis. Other Members present: Rosie Cooper; Damian Collins; Gill Furniss; Gareth Bacon; Jamie Stone; Ben Bradley; Tahir Ali; Brendan Clarke-Smith; Allan Dorans; Virginia Crosbie; Mr Gregory Campbell; Simon Jupp; Jeff Smith; Huw Merriman; Chris Bryant; Mark Eastwood; Ian Paisley; John Nicolson; Chris Matheson; Rt Hon Mr John Whittingdale OBE, Minister for Media and Data. Questions 1-21 Chair: Thank you all for joining us today. Today’s e-petition session has been scheduled to give Members from across the House an opportunity to discuss TV licensing. Sessions like this would normally take place in Westminster Hall, but due to the suspension of sittings, we have started holding these sessions as an alternative way to consider the issues raised by petitions and present these to Government. We have received more requests to take part than could be accommodated in the 90 minutes that we are able to schedule today. Even with a short speech limit for Back- Bench contributions, it shows just how important this issue is to Members right across the House. I am pleased to be holding this session virtually, and it means that Members who are shielding or self-isolating, and who are unable to take part in Westminster Hall debates, are able to participate. I am also pleased that we have Front-Bench speakers and that we have the Minister attending to respond to the debate today. -

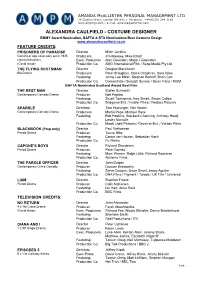

Alexandra Caulfield - Costume Designer

AMANDA McALLISTER PERSONAL MANAGEMENT LTD 74 Claxton Grove, London W6 8HE • Telephone: +44(0)207 244 1159 www.ampmgt.com • e-mail: [email protected] ALEXANDRA CAULFIELD - COSTUME DESIGNER EMMY Award Nomination, BAFTA & RTS Nominations Best Costume Design www.alexandracaulfield.co.uk FEATURE CREDITS: PRISONERS OF PARADISE Director Mitch Jenkins Coming of age Love story set in 1925 Producers Jim Mooney, Mike Elliott colonial Mauritius Exec. Producers Alan Govinden, Maria J Govinden (Covid shoot) Production Co. AMG International Film / Sega Media Pty Ltd THE FLYING SCOTSMAN Director Douglas Mackinnon Bio Drama Producers Peter Broughan, Claire Chapman, Sara Giles Featuring Jonny Lee Miller, Stephen Berkoff, Brian Cox Production Co. ContentFilm / Scottish Screen / Scion Films / MGM BAFTA Nominated Scotland Award Best Film THE BEST MAN Director Stefan Schwartz Contemporary Comedy Drama Producer Neil Peplow Featuring Stuart Townsend, Amy Smart, Simon Callow Production Co. Endgame Ent. / Insider Films / Redbus Pictures SPARKLE Directors Tom Hunsinger, Neil Hunter Contemporary Comedy Drama Producers Martin Pope, Michael Rose Featuring Bob Hoskins, Stockard Channing, Anthony Head, Lesley Manville Production Co. Magic Light Pictures / Revolver Ent. / Vertigo Films BLACKBOOK (Prep only) Director Paul Verhoeven Period Drama Producer Teune Hilte Featuring Carice van Houten, Sebastian Koch Production Co. Fu Works CAPONE’S BOYS Director Richard Standeven Period Drama Producer Peter Barnes Featuring Marc Warren, Ralph Little, Richard Rowntree Production Co. Alchemy Films THE PAROLE OFFICER Director John Duigan Contemporary Crime Comedy Producer Duncan Kenworthy Featuring Steve Coogan, Omar Sharif, Jenny Agutter Production Co. DNA Films / Figment / Toledo / UK Film / Universal LIAM Director Stephen Frears Period Drama Producer Colin McKeown Featuring Ian Hart, Anne Reid Production Co. -

Current Film Slate

CURRENT PROJECTS Updated 06 August 2021 For more information on any of the projects listed below, please contact the Premier film team as follows: • Email: [email protected] • Visit our website: https://www.premiercomms.com/specialisms/film/public-relations UK DISTRIBUTION NIGHT OF THE KINGS UK release date: 23 July 2021 (in cinemas) Directed by: Philippe Lacôte Starring: Koné Bakary, Barbe Noire, Steve Tientcheu, Rasmané Ouédraogo, Issaka Sawadogo, Digbeu Jean Cyrille Lass, Abdoul Karim Konaté, Anzian Marcel Laetitia Ky, Denis Lavant Running time: 93 mins Certificate: 12A UK release: 23 July 2021 Premier contacts: Annabel Hutton, Simon Bell, Josh Glenn When a young man (first-timer Koné Bakary) is sent to an infamous prison, located in the middle of the Ivorian forest and ruled by its inmates, he is chosen by the boss 'Blackbeard' (Steve Tientcheu, BAFTA and Academy-Award nominated LES MISÉRABLES) to take part in a storytelling ritual just as a violent battle for control bubbles to the surface. After discovering the grim fate that awaits him at the end of the night, Roman begins to narrate the mystical life of a legendary outlaw to make his story last until dawn and give himself any chance of survival. JOLT UK release date: 23 July 2021 (Amazon Prime Video) Directed by: Tanya Wexler Starring: Kate Beckinsale, Bobby Cannavale, Jai Courtney, Laverne Cox, David Bradley, Ori Pfeffer, Susan Sarandon, Stanley Tucci Running time: 91 mins Certificate: TBC UK release: Amazon Studios Premier contacts: Matty O’Riordan, Monique Reid, Brodie Walker, Priyanka Gundecha Lindy is a beautiful, sardonically-funny woman with a painful secret: Due to a lifelong, rare neurological disorder, she experiences sporadic rage-filled, murderous impulses that can only be stopped when she shocks herself with a special electrode device. -

Select Committee of Tynwald on the Television Licence Fee Report 2010/11

PP108/11 SELECT COMMITTEE OF TYNWALD ON THE TELEVISION LICENCE FEE REPORT 2010/11 REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE OF TYNWALD ON THE TELEVISION LICENCE FEE At the sitting of Tynwald Court on 18th November 2009 it was resolved - "That Tynwald appoints a Committee of three Members with powers to take written and oral evidence pursuant to sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, as amended, to investigate the feasibility and impact of withdrawal from or amendment of the agreement under which residents of the Isle of Man pay a television licence fee; and to report." The powers, privileges and immunities relating to the work of a committee of Tynwald are those conferred by sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, sections 1 to 4 of the Privileges of Tynwald (Publications) Act 1973 and sections 2 to 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1984. Mr G D Cregeen MHK (Malew & Santon) (Chairman) Mr D A Callister MLC Hon P A Gawne MHK (Rushen) Copies of this Report may be obtained from the Tynwald Library, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IM7 3PW (Tel 07624 685520, Fax 01624 685522) or may be consulted at www, ,tynwald.orgim All correspondence with regard to this Report should be addressed to the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IMI 3PW TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. The broadcasting landscape in the Isle of Man 4 Historical background 4 Legal framework 5 The requirement to pay the licence fee 5 Whether the licence fee is a UK tax 6 Licence fee collection and enforcement 7 Infrastructure for terrestrial broadcasting 10 Television 10 Radio: limitations of analogue transmission capability and extent of DAB coverage 13 3. -

Michelle Heaney Editor

AMANDA MCALLISTER PERSONAL MANAGEMENT LTD 74 Claxton Grove, London W6 8HE • Telephone: +44 (0) 207 244 1159 www.ampmgt.com • e-mail: [email protected] MICHELLE HEANEY EDITOR CREDITS INCLUDE: THE REUNION Director Bill Eagles Thriller Drama Series Producer Sydney Gallonde Episodes 2, 4 & 6 (Remote editing) Production Co. MGM International TV Prods / Make It Happen Studio / France Télévisions STAY CLOSE Director Lindy Heymann 8 x 1hr Contemporary Drama Producer Juliet Charlesworth Episodes 5 & 6 Exec. Producers Nicola Shindler, Harlan Coben, Richard Fee, Danny Brocklehurst Production Co. Red Production Company / Netflix TRACES Director Rebecca Gatward 2 x 1hr Crime Mystery Thriller Drama Producer Juliet Charlesworth (Additional Editor) Exec. Producers Nicola Shindler, Michaela Fereday, Liam Keelan Philippa Collie Cousins, Val McDermid Production Co. Red Production Company / ALIBI BAFTA Nomination Best Drama Series THE WORST WITCH Director Dermot Boyd 4 x ½hr Children’s Drama Series Producer Kim Crowther Exec. Producer Sue Knott Production Co. CBBC / Netflix / ZDF Enterprises THE STRANGER Director Daniel O’Hara 3 x 1hr Mystery Crime Drama Producer Madonna Baptiste (1st Assistant Editor) Exec. Producers Nicola Shindler, Harlan Coben, Danny Brocklehurst, Richard Fee Editor Steve Singleton Production Co. Red Production Company / Netflix BRASSIC Directors Daniel O'Hara, Jon Wright 6 x 1hr Comedy Series Producer Juliet Charlesworth (1st Assistant Editor/ Assembly Editor) Exec. Producers David Livingston, Joe Gilgun, Danny Brocklehurst, Jon Montague Editors Annie Kocur, Rachel Hoult Production Co. SKY / Calamity Films THE ROOK Director Kari Skogland 3 x 1hr Fantasy Thriller Drama Series Producer Steve Clark-Hall (1st Assistant Editor) Exec. Producer Stephen Garrett Editor Oral Ottey Production Co. -

Oxford Lecture 1 - Final Master

OXFORD LECTURE 1 - FINAL MASTER HOW TO GROW A CREATIVE BUSINESS BY ACCIDENT The legendarily bullish film director Alan Parker once adapted Shaw's famous dictum about the academic profession - "those who can, do. Those who can't teach." So far so familiar. And to many in this room, no doubt, so annoying. But he went on: "those who can't teach, teach gym. And those who can't teach gym, teach at film school." I appreciate that Oxford is not a film school, though it has a more distinguished record than any film school for supplying the talent that has fuelled the British film and TV industries for almost a century - on and off camera. Writers like Richard Curtis, who brought us 4 Weddings and a Funeral, Love Actually, The Vicar of Dibley and Blackadder; or The Full Monty and Slumdog Millionaire scribe Simon Beaufoy; directors of the diversity of Looking for Eric's Ken Loach and 24 Hour Party People's Michael Winterbottom; writer/directors like Monty Python's Terry Jones and the Thick of It's Armando Iannucci; actors and performers ranging from Hugh Grant to Rowan Atkinson; and broadcasting luminaries like the BBC's Director General Mark Thompson and News International's very own Rupert Murdoch. So, Oxford has been a pretty efficient film and TV school, without even trying. And perhaps that is Parker's point. Can what passes for creativity in film and TV ever really be taught? But here in my capacity as News International Visiting Professor of Broadcast Media (or if you prefer an acronym, NIVPOB - the final M is silent) I may be even further down Parker's food chain. -

James Cooper Avid and FCP Editor

James Cooper Avid and FCP Editor Profile James is a fast, creative and reliable editor with 10 years broadcast experience. Always calm, patient and personable, he works happily alongside directors and producers but he is also used to editing unattended. James prides himself in always getting the job done on time and to the very highest standard. His particular strengths are include narrative structure, visual creativity and working with music. He is skilled in all versions of Avid, specializing in offline editing, although he does have previous experience in online editing and grading. He also uses Final Cut Pro, and has his own home setup including DVD Studio Pro for authoring DVDs and Motion for creating motion graphics. As a sideline to editing factual television, he has written, directed and edited drama shorts, winning several film festival awards. Documentary Tiny Tots Talent Agency – TwoFour for Channel 4 (1 x 60 min) Documentary series following child talent agency Bizzy Kidz and the wannabe stars of the future starting out on their journey to fame and fortune. Producer/Director: Stevey Jones; Series Director: Fay Gibson; Executive Producer: David Clews. Avid offline. Love The Day - Minnow Films for Channel 4 (1 x 60 min) Documentary following the off-kilter world of Stalkie, a self-made life coach and business guru.Director: Andy Oxley; Executive Producer: Colin Barr. Avid offline. How to Live the Chelsea Life – Special Edition Films for Channel 4 (1 x 60 min) Observational documentary following entrepreneur Adam Goff and his company, a highly selective house sharing property ‘club’ which boasts the opportunity to offer young professionals in London a millionaire’s lifestyle.