The Ultimate Judgment of History” the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Almanac, November 1962, Vol. 9, No. 3

Research Grants, Fellowships Management Committee Reports Now Available to Faculty To President's Staff Conference The University's Committee on the Advancement of A four-point program designed to strengthen and sys- Research has announced plans to award ten Summer tematize the methods by which the University recruits and Research Fellowships for 1963. In keeping with University retains administrative staff personnel was submitted this policy of providing more generous support for faculty month to the President's Staff Conference by the newly research, these awards have been increased in number and organized Committee on Management Development. the stipend raised to $1500. The program, which the Conference has asked the Com- Competition for these fellowships is open to all full-time mittee to find means of implementing, contains these members of the faculty who hold a doctorate or its equiva- points: lent. While appointments will be based primarily on the 1. The Committee on Management Development should merit of projects proposed and on the research potential be established as a standing committee. of applicants, preference is given to applications from 2. The Committee should have the responsibility of younger members of the faculty and those from the lower seeing that periodic evaluations are made of the abilities, academic ranks. experience, and performance of the present administrative The committee also has somewhat greater resources for personnel, so that those staff members who show the great- its regular grants in aid of research than it has had in est promise of further development can be identified. recent years. These grants provide for clerical or technical 3. -

The ICRC and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, Le CICR Et La Crise

RICR Juin IRRC June 2001 Vol. 83 No 842 287 The ICRC and the 1962 Cuban missile crisis by Thomas Fischer n 6 November 1962, the Swiss ambassador and former President of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Paul Rüegger, embarked on a delicate mission to negotiate with the United Nations OSecretary-General and the representatives of the two superpowers and Cuba in New York. His task was to specify and obtain prior acceptance of the conditions under which the ICRC was prepared to lend its good offices to the United Nations and the parties involved in the Cuban missile crisis, so as to help ease the tension that had arisen from the secret introduction of Soviet nuclear weapons in the Caribbean. This article deals with the unusual role the ICRC was ready to play in that crisis and sheds new light on how it came to be engaged in these highly political matters. New American, Soviet and Cuban sources that have become known since 1990 reveal in great detail the events surround- ing the planned ICRC intervention in the missile crisis. It is a story that has so far remained untold. Most of the new material is to be found in the microfiche collection of declassified documents on the Cuban missile crisis compiled and made available by the National Thomas Fischer is a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Political Science, University of Zurich, Switzerland, and a research assistant at the Center for International Studies (CIS), Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich. 288 The ICRC and the 1962 Cuban missile crisis Security Archive, a private research institution in Washington DC.1 The collection also contains the relevant documents of the United Nations Archives in New York. -

13 Introduction to the Statutes and Regulations

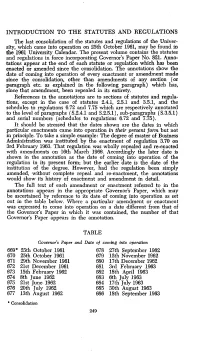

INTRODUCTION TO THE STATUTES AND REGULATIONS The last consolidation of the statutes and regulations of the Univer sity, which came into operation on 25th October 1961, may be found in the 1961 University Calendar. The present volume contains the statutes and regulations in force incorporating Governor's Paper No. 821. Anno tations appear at the end of each statute or regulation which has been enacted or amended since the consolidation. The annotations show the date of coming into operation of every enactment or amendment made since the consolidation, other than amendments of any section (or paragraph etc. as explained in the following paragraph) which has, since that amendment, been repealed in its entirety. References in the annotations are to sections of statutes and regula tions, except in the case of statutes 2.4.1, 2.5.1 and 3.5.1, and the schedules to regulations 6.72 and 7,75 which are respectively annotated to the level of paragraphs (S.2.4.1 and S.2.5.1), sub-paragraphs (S.3.5.1) and serial numbers (schedules to regulations 6.72 and 7.75). It should be stressed that the dates shown are the dates in which particular enactments came into operation in their present form but not in principle. To talce a simple example: The degree of master of Business AoSriinistration was instituted by the enactment of regulation 3.70 on 3rd February 1963. That regulation was wholly repealed and re-enacted with amendments on 16th March 1966. Accordingly the later date is shown in the annotation as the date of coming into operation of the regulation in its present form; but the earlier date is the date of the institution of the degree. -

World Economic Survey 1962

WORLD ECONOMIC SURVEY 1962 II. Current Economie Developments UNITED NATIONS Department of Economic and Social Affairs WOR D ECO OMIC SURVEY 1962 II. Current Economic Developments UNITED NATIONS New York, 1963 E/3761/Rev.l ST/ECA/78 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No.: 63. II.C. 2 Price: $U.5. 1.50 (or equivalent in other currencies) FOREWORD This report represents part II of the World Economic Survey, 1962. As indicated in the Foreword to part I, "The Developing Countries in World Trade" (Sales No.: 63.II.C.1), it consists of three chapters dealing with recent developments in the world economy. Chapter 1 analyses the situation in the industrially advanced private enterprise countries. Chapter 2 reviews current trends in the countries that are heavily dependent on the export of primary commodities. Chapter 3 provides an account of recent changes in the centrally planned economies. The three chapters follow a brief introduction which draws attention to some of the salient features of the current situation. Most of the analysis is concerned with the calendar year 1962; chapters 1 and 2 conclude with brief assessments of the outlook for 1963. These discussions of outlook draw to a large extent on the replies of Governments to a questionnaire on economic trends, problems and policies circulated by the Secretary-General in November 1962. Like part I, part II of the World Economic Survey, 1962 was prepared in the Department of Economic and Social Affairs by the Bureau of General Economic Research and Policies. iii EXPLANATORY NOTES The following -

221 the Dates of Publication of Crustaceana Vols. 1-50

221 THE DATES OF PUBLICATION OF CRUSTACEANA VOLS. 1-50 AND SUPPL. 1-10 BY L. B. HOLTHUIS Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden, Netherlands Now that 50 volumes of Crustaceana have been published it seems a fitting occasion to give a list of the dates of publication of the various parts and of the supplements. The actual dates in some cases are different from those printed on the covers, although in only a very few cases this discrepancy is serious. I am most indebted to Mr. P. A. Kranenburg of Messrs. E. J. Brill for providing me with these data, viz., the data that the copies were sent out. The data of supplements 1 to 3 incl. and 5 could not be found in the files of Brill's; the ones given here are those on which the copies were received by the library of the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, they are at the most 1 or 2 days later than the actual dates of publication. CRUSTACEANA, VOLS. 1-50 1 (1), 25 January 1960; 1 (2), 19 May 1960; 1 (3), 24 August 1960; 1 (4), 12 October 1960. 2 (1), 20 February 1961; 2 (2), 8 April 1961; 2 (3), 21 June 1961; 2 (4), 4 August 1961. 3 (1), 18 August 1961; 3 (2), 29 July 1961; 3 (3), 15 February 1962; 3 (4), 15 March 1962. 4 (1), 27June 1962; 4 (2), 4 July 1962; 4 (3), 10 September 1962; 4 (4), 6 November 1962. 5 (1), 30 January 1963; 5 (2), 28 March 1963; 5 (3), 22 May 1963; 5 (4), 15 July 1963. -

Cuban Missile Crisis Operations

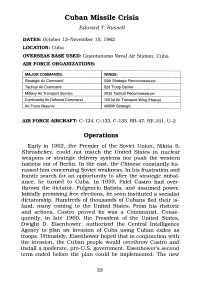

Cuban Missile Crisis Edward T. Russell DATES: October 13-November 15, 1962 LOCATION: Cuba OVERSEAS BASE USED : Guantanamo Naval Air Station, Cuba AIR FORCE ORGANIZATIONS : MAJOR COMMANDS: WINGS: Strategic Air Command 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Tactical Air Command 62d Troop Carrier Military Air Transport Service 363d Tactical Reconnaissance Continental Air Defense Command 1501 st Air Transport Wing (Heavy) Air Force Reserve 4080th Strategic AIR FORCE AIRCRAFT: C-124, C-133, C-135, RB-47, RF-101, U-2 Operations Early in 1962, the Premier of the Soviet Union, Nikita S . Khrushchev, could not match the United States in nuclear weapons or strategic delivery systems nor push the western nations out of Berlin. In the east, the Chinese constantly ha- rassed him concerning Soviet weakness. In his frustration and frantic search for an opportunity to alter the strategic imbal- ance, he turned to Cuba . In 1959, Fidel Castro had over- thrown the dictator, Fulgencio Batista, and assumed power. Initially promising free elections, he soon instituted a socialist dictatorship . Hundreds of thousands of Cubans fled their is- land, many coming to the United States . From his rhetoric and actions, Castro proved he was a Communist. Conse- quently, in late 1960, the President of the United States, Dwight D . Eisenhower, authorized the Central Intelligence Agency to plan an invasion of Cuba using Cuban exiles as troops . Ultimately, Eisenhower hoped that in conjunction with the invasion, the Cuban people would overthrow Castro and install a moderate, pro-U.S . government. Eisenhower's second term ended before the plan could be implemented . The new 33 SHORT OF WAR president, John F. -

28 January 1965 TARIFFS and TRADE Limited Distribution

RESTRICTED GENERAL AGREEMENT ON 28 January 1965 TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution Original: English ACCESSION OF YUGOSLAVIA The following communication dated 27 January has been received from the head of the Yugoslav delegation in Geneva. On the basis of the Declaration of 13 November 1962 and the Decision of the same date concerning the participation of Yugoslavia in the work of the CONTRACTfIG PARTIES my country has -,he status of a provisional member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. The validity of the Declaration and the Decision expires at the end of this year. Accordingly, I have the honour to inform you that my Government has decided to participate in the Kennedy negotiations with a view to its full accession to the General Agreement. My Government expects that the terms of participation of Yugoslavia as a less- developed country in the trade negotiations and its accession to the GATT will be governed by the principles and decisions adopted at the meeting of Ministers in Stay 1963 and in Pay 1964 and the provisions of the new chapter on trade and develop- ment, as well as by the general conditions of participation in the Kennedy Round to be set for the less-developed contracting parties. The Yugoslav Government is convinced that its decision will promote the realisa- tion of the purposes set forth in the Declaration of 13 November 1962 and that it will make a contribution to the objectives of the General Agreement. Finally, I have the honour to communicate that, in view of the foregoing. my Government expects also that the validity of the said Declaration and Decision will be further extended,, if the Kennedy negotiations are not completed by the end of this year, ./.. -

Membership of the Bureau of the General Conference

MEMBERSHIP OF THE BUREAU OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE States Date of entry Number of times member of Bureau Afghanistan 4 May 1948 6 Albania 16 October 1958 3 Algeria 15 October 1962 9 Andorra 20 October 1993 – Angola 11 March 1977 4 Antigua and Barbuda 15 July 1982 – Argentina 15 September 1948 16 Armenia 9 June 1992 – Australia 4 November 1946 19 Austria 13 August 1948 9 Azerbaijan 3 June 1992 2 Bahamas 23 April 1981 1 Bahrain 18 January 1972 2 Bangladesh 27 October 1972 3 Barbados 24 October 1968 9 Belarus 12 May 1954 – Belgium 29 November 1946 11 Belize 10 May 1982 – Benin 18 October 1960 5 Bhutan 13 April 1982 – Bolivia, Plurinational State of 13 November 1946 – Bosnia and Herzegovina 2 June 1993 3 Botswana 16 January 1980 1 Brazil 4 November 1946 22 Brunei Darussalam 17 March 2005 – Bulgaria1 17 May 1956 7 Burkina Faso 14 November 1960 2 Burundi 16 November 1962 5 Cambodia2 3 July 1951 – Cameroon 11 November 1960 10 Canada 4 November 1946 20 Cabo Verde 15 February 1978 1 Central African Republic 11 November 1960 3 Chad 19 December 1960 2 Chile 7 July 1953 9 China 4 November 1946 20 Colombia 31 October 1947 6 Comoros 22 March 1977 2 Congo 24 October 1960 2 Cook Islands 25 October 1989 – Costa Rica 19 May 1950 7 Côte d’Ivoire 27 October 1960 6 Croatia 1 June 1992 5 Cuba 29 August 1947 13 Cyprus 6 February 1961 – 1 At the 35th session of the General Conference, Bulgaria was a member of the Bureau in two capacities (Vice- President of the General Conference and Chairperson of the SC Commission). -

Survey of Current Business November 1962

NOVEMBER 1962 survey of CURRENT BUSINESS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE OFFICE OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS NOVEMBER 1962 VOL. 42, NO. II U.S. Department of Commerc Luther H. Hodges Secretary Office of Business Economics M. Joseph Meehan Director THE BUSINESS SITUATION PAGE Louis J. Paradiso Summary * . 1 Managing Director Automobile Purchases at Record Pace—Personal Income Up—Indus- trial Production Steady Murray F. Foss Financial Conditions Ease 2 Editor Expansion in Government Programs in Fiscal 1963 4 K. Celeste Stokes Billy Jo Dawl Statistics Editor Graphics GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT AND INCOME IN STAFF CONTRIBUTORS QUARTER 6 TO THIS ISSUE Expansion in Final Purchases ,«,«,.» 7 Business Review and Feature: Inventory Buying Slackens *... *. 7 John A. Gorman ARTICLES Helen B. Junz EXPANSION OF FIXED CAPITAL IN THE UNITED STATES National Income and Product: Rapid Postwar Growth—-Rise Slackens. 9 Frederick M. Cone Postwar Investment Greatly Increases Stock of Fixed Capital—Rate Articles: of Increase in Equipment Stocks Tapers Off, While Stocks of Structures George Jaszi Continue to Grow Robert C. Wasson Lawrence Grose CORPORATE PROFITS AND NATIONAL OUTPUT E. Lynn Williamson Profits Share Declines in Postwar Period 19 Robert E. Graham, Jr. Trend Over Postwar Period Reviewed—Effect on Corporate Profits and Jaeqtielin Bauman National Income of Changes in Treasury Regulations—"Quarterly Annette R. Presley Measure of Corporate Gross Profit NEW OR REVISED STATISTICAL Subscription prices, including week Industrial Production Index on New Base. * ,.....*..... S3 statistical supplements, are $4 a year f Building Cost Index (AGC) on New Base. S9 domestic and $7.50 for foreign mailing. Sing Commercial Bank Credit (Seasonally Adjusted), New S17 issue 30 cents. -

General Ageementon L/1907

GENERAL AGEEMENTON L/1907. TARIFFS AND TRADE 14 November 1962 Limited Distribution CONTARCTING PARTIES Twentieth Session PROVISIONAL ACCESSION OF ARGENTINA Extension of the Declaration of 18 November 1960 Procès-verbal dated 7 November 1962 The parties to the Declaration on the ProvisionalAccession of Argentina to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, of 18 November 1960 (hereinafter referred to as "the Declaration of 18 November 1960'' and "the General Agreement" TespectiveLy), Desiring to extend the Declaration pursuant to paragraph 4, Acting pursuant to paragraph 4 thereof: Agree: 1. The period of validity of the Declaration of 18 November 1960 is extended for two years by changing the date in paragraph 4 from "31 December 1962" to "31 December 1964". 2. This Procè-verbal shall be deposited with the Exeoutive Secretary of the CONTRACTING PARTIES to the General Agreement. It shall remain open for acceptance, by signature or otherwise, by Argentina, by the participating govern- ments to the Declaration of 18 November 1960, and by contracting parties to the General Agreement and other governments following their acceptance of the Declaration of 18 November 1960. 3. This Procès-verbal shall enter into force upon its acceptance by all the parties to the Declaration of 18 November 1960; provided that if it shall not have been accepted by all such parties by 31 December 1962, (a) it shall enter into force in respect of those parties thereto which shall have accepted it as soon as it shall have been accepted by Argentina and any other such party; and (b) it shall enter into force for any such party subsequently accepting it upon such acceptance or upon the entry into force of the Declaration of 18 November 1960 in respect of is the later. -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

KEg/ifilCIED GENERAL AGREEMENT ON L/19^7 13 December 1962 TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution NEWLY INDEPENDENT STATES Status under Recommendations of 18 November i960, 9 December 196l and 14 November 1962 By the Recommendation of 18 November i960 (9S/l6) contracting parties are recommended to continue for a period of two years to apply the GATT, on a de facto basis and subject to reciprocity, in their relations with territories which acquire full autonomy in the conduct of their external commercial relations and of other matters provided for in the General Agreement but which require some time to consider their future commercial policy and the question of their relations with the GATT. Under the Recommendation of 9 December 1961 (lOS/17), this de facto application is to be extended for a further year in respect of States which request this longer period in which to decide upon their future relations with the GATT. For certain States in Africa, the period was again extended, by the Decision of 14 November 1962 (L/1934), until the close of the last ordinary session of the CONTRACTING PARTIES in 1963.I The following is the situation in respect of the States to which the Recommendations are at present applicable: Expiry date under Extended expiry date Recommendation of I960 under Recommendation (2 years after date of of 1961 or 1962 independence) Algeria 3 July 1964 Burundi 1 July 1964 •Cameroun 1 January 1962 15 November 1963 •Central African Republic 14 August 1962 15 November 1963 *Chad 11 August 1962 15 November 1963 •Congo (Brazzaville) -

Wood Hill Herald 1962-11-01, (November, 1962) Wood Hill Herald Staff Writer

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Park Forest South Regional Archives 11-1-1962 Wood Hill Herald 1962-11-01, (November, 1962) Wood Hill Herald staff writer Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/region_pfs Recommended Citation Wood Hill Herald staff writer, "Wood Hill Herald 1962-11-01, (November, 1962)" (1962). Park Forest South. 22. http://opus.govst.edu/region_pfs/22 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Regional Archives at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Park Forest South by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ELECTED ( Wood Hill HERALD NOVEMBER 1962 Politics in II Politics came to Wood Hill prior the November 6 elections. This was the first time that a large enough segment of Wood Hill vo- ters could cast ballots enough to be considered an Important factor in the votes cast in Dis- trict 4 of the Monee Precinct. Each party waged entirely diff- erent campaigns. The Democratic Party sponsored motorcades, the traditional rally, etc. Repub- licans ran more to "base roots" organization, "coffees" and an even greater reliance on the use of Block Captains. Traditionally the vote in Dist- rict 4 has been about 3 to 1 in favor of Republican candidates. RESULTS (District 4): Final results from this area are Senator-Dirksen 431; Yates 201 tabulated here. However, it is Treasurer-Scott 421; Lorenz 208 interesting to note that the Supt Ins-Page 410; Wilkins 217 voting as shown has not upset Clerk, Supreme Court- the "traditional" balance.