Bleeding Bile (Hemobilia): an Obscure Cause of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Case Report and Review of the Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Report Acute Pancreatitis Secondary to Hemobilia After Percutaneous Liver Biopsy: a Rare Complication of a Common Procedure, Presenting in an Atypical Fashion

Hindawi Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine Volume 2018, Article ID 1284610, 4 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1284610 Case Report Acute Pancreatitis Secondary to Hemobilia after Percutaneous Liver Biopsy: A Rare Complication of a Common Procedure, Presenting in an Atypical Fashion Ramy Mansour and Justin Miller Genesys Regional Medical Center Gastroenterology, 1 Genesys Parkway, ATTN: Medical Education, Grand Blanc, MI 48439, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Ramy Mansour; [email protected] Received 4 June 2018; Accepted 16 August 2018; Published 2 September 2018 Academic Editor: Engin Altintas Copyright © 2018 Ramy Mansour and Justin Miller. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Percutaneous Liver Biopsy is an ofen-required procedure for the evaluation of multiple liver diseases. Te complications are rare but well reported. Here we present a case of a 60-year-old overweight female who underwent liver biopsy for elevated alkaline phosphatase. She developed acute pancreatitis secondary to hemobilia, with atypical signs and symptoms, following the biopsy. She never had the classic triad of RUQ pain, jaundice, and upper GI hemorrhage. Tere were also multiple negative imaging studies, thus complicating the presentation. She was successfully treated with ERCP, sphincterotomy, balloon sweep, and stent placement. Angiography and transcatheter embolization were not required. 1. Introduction complained of hematuria during the review of systems. A CT scan was performed without contrast for the hematuria and Histological assessment of the liver is the gold standard for revealed difuse hepatic steatosis. -

Abdominal Distension

2003 OSCE Handbook The world according to Kelly, Marshall, Shaw and Tripp Our OSCE group, like many, laboured away through 5th year preparing for the OSCE exam. The main thing we learnt was that our time was better spent practising our history taking and examination on each other, rather than with our noses in books. We therefore hope that by sharing the notes we compiled you will have more time for practice, as well as sparing you the trauma of feeling like you‟ve got to know everything about everything on the list. You don‟t! You can‟t swot for an OSCE in a library! This version is the same as the 2002 OSCE Handbook, except for the addition of the 2002 OSCE stations. We have used the following books where we needed reference material: th Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine, 4 Edition, R A Hope, J M Longmore, S K McManus and C A Wood-Allum, Oxford University Press, 1998 Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties, 5th Edition, J A B Collier, J M Longmore, T Duncan Brown, Oxford University Press, 1999 N J Talley and S O‟Connor, Clinical Examination – a Systematic Guide to Physical Diagnosis, Third Edition, MacLennan & Petty Pty Ltd, 1998 J. Murtagh, General Practice, McGraw-Hill, 1994 These are good books – buy them! Warning: This document is intended to help you cram for your OSEC. It is not intended as a clinical reference, and should not be used for making real life decisions. We‟ve done our best to be accurate, but don‟t accept any responsibility for exam failure as a result of bloopers…. -

A Rare Case of Fulminant Hemobilia Resulting from Gallstone Erosion of the Right Hepatic Artery

CASE REPORT A Rare Case of Fulminant Hemobilia Resulting From Gallstone Erosion of the Right Hepatic Artery Shir Li JEE, MRCS (Edin)*; Kin Foong LIM, FRCS (IRE)**; KRISHNAN Raman, FRCS (Edin)*** *Surgical Trainee, General Surgery, Hospital Selayang, Lebuhraya Selayang-Kepong, Batu Caves, Selangor 68100, Malaysia, **Consultant Hepatobiliary Surgeon, Hepatobiliary Department, Hospital Selayang, ***Senior Consultant Hepatobiliary Surgeon, Hepatobiliary Department, Hospital Selayang µmol/L with predominant direct hyperbilirubinaemia and SUMMARY serum alkaline phosphotase of 208 U/L. The renal profile Hemobilia is a rare but potentially lethal condition. The and tumour markers were normal. commonest cause of hemobilia is trauma, accounting up to 85% of all cases. Hemobilia caused by gallstones is very An oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGDS) was performed rare. Most of the cases of hemobilia are either managed but failed to identify any active bleeding lesion. A side conservatively or treated by embolization. Surgery is viewing duodenoscopy subsequently revealed intermittent indicated only when there is an associated surgical blood and pus oozing from the papilla of Vater. Endoscopic condition or when embolization fails. We report a case of a retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and common 72-year-old patient with massive hemobilia caused by bile duct stenting were carried out. The cholangiogram did gallstone erosion to the adjacent artery, diagnosed intra- not show any filling defect. In view of the finding of operatively. The complication was successfully managed by haemobilia, an abdominal computerised tomography cholecystectomy and repair of the bleeding vessel. This angiography (CTA) was done. The CTA did not reveal any case highlights the importance that hemobilia should be active contrast extravasation and all visualized vessels were suspected in patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal normal in caliber. -

Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS); Review of Initial Experience at Aga Khan University Hospital Rana Shoaib Hamid Aga Khan University

eCommons@AKU Department of Radiology Medical College, Pakistan April 2011 Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS); review of initial experience at Aga Khan University Hospital Rana Shoaib Hamid Aga Khan University Tanveer-ul-haq Aga Khan University Muhammad Azeemuddin Aga Khan University Zafar Sajjad Aga Khan University Ishtiaq Chishti Aga Khan University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_radiol Part of the Radiology Commons Recommended Citation Hamid, R., Tanveer-ul-haq, ., Azeemuddin, M., Sajjad, Z., Chishti, I., Salam, B. (2011). Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS); review of initial experience at Aga Khan University Hospital. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 61(4), 336-9. Available at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_radiol/25 Authors Rana Shoaib Hamid, Tanveer-ul-haq, Muhammad Azeemuddin, Zafar Sajjad, Ishtiaq Chishti, and Basit Salam This article is available at eCommons@AKU: http://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_radiol/25 Original Article Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS); review of initial experience at Aga Khan University Hospital Rana Shoaib Hamid, Tanveer-ul-Haq, Muhammad Azeemuddin, Zafar Sajjad, Ishtiaq Chishti, Basit Salam Radiology Department, Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan. Abstract Objective: To retrospectively assess the therapeutic effectiveness and safety of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in patients with portal hypertension related complications. Methods: Over a period of 7.5 years 19 patients (10 males and 9 females, age range 25-69 years) were referred for TIPS at our radiology department. Thirteen patients suffered from liver cirrhosis while 6 had Budd Chiari syndrome. All patients were evaluated with colour doppler ultrasonography and cross sectional imaging. -

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: a Rare Complication of Acute Cholecystitis

CASE REPORT – OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 4 (2013) 761–764 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector International Journal of Surgery Case Reports journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijscr Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A rare complication of acute cholecystitis a,∗ b b a Gael R. Nana , Matthew Gibson , Archie Speirs , James R. Ramus a Department of Surgery, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, Berkshire RG1 5AN, UK b Department of Radiology, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, Berkshire RG1 5AN, UK a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: INTRODUCTION: Haemobilia is a rare complication of acute cholecystitis and may present as upper gas- Received 28 May 2013 trointestinal bleeding. Received in revised form 31 May 2013 PRESENTATION OF CASE: We describe two patients with acute cholecystitis presenting with upper gas- Accepted 31 May 2013 trointestinal bleeding due to haemobilia. Bleeding from the duodenal papilla was seen at endoscopy Available online 15 June 2013 in one case but none in the other. CT demonstrated acute cholecystitis with a pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery in both cases. Definitive control of intracholecystic bleeding was achieved in both cases by Keywords: embolisation of the cystic artery. Both patients remain symptom free. One had subsequent laparoscopic Haemobilia Pseudoaneurysm cholecystostomy and the other no surgery. Cholecystitis DISCUSSION: Pseudoaneurysms of the cystic artery are uncommon in the setting of acute cholecystitis. Transarterial embolisation OGD and CT angiography play a key role in diagnosis. -

Anaemia in Alimentary Tract Disease

Open Access Austin Journal of Gastroenterology Review Article Anaemia in Alimentary Tract Disease Weledji EP* Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, Abstract University of Buea, S.W. Region, Cameroon, W/Africa Blood loss from the alimentary tract may be chronic and occult resulting *Corresponding author: Elroy Patrick Weledji, in anaemia, or, acute requiring emergency resuscitation, investigation and Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, management. Anaemia in alimentary tract disease usually results from deficiency University of Buea, S.W. Region, Cameroon, W/Africa of iron, vitamin B12 or folic acid. In this review, the common causes of chronic anaemia manifesting in the alimentary tract are discussed. The importance of Received: April 06, 2019; Accepted: May 03, 2019; clinically diagnosing and treating the underlying disease is emphasized. Published: May 10, 2019 Keywords: Bleeding; Chronic; Anaemia; Disease; Alimentary tract Introduction chronic blood loss is located in the small bowel [1,2-4,7,9]. Anaemia may be the result of blood loss due to a number of Iron-deficiency anaemia causes in the gastrointestinal tract. The loss can be obvious and Although the major cause of iron deficiency anaemia is blood spectacular as in bleeding oesophageal varices, peptic ulcer, or loss from the alimentary tract, in women menstrual blood loss must insidious and occult from a colonic polyp. Anaemia can also be also be considered. In some cases of chronic and occult blood loss the due to malabsorption of iron, folate, and vitamin B12 because of patient may present with symptoms of anaemia, such as, dyspnoea, a variety of disease, or can simply reflect an inadequate dietary dizziness, or angina. -

Acute Cholangitis: Diagnosis and Management

Journal of Visceral Surgery (2019) 156, 515—525 Available online at ScienceDirect www.sciencedirect.com REVIEW Acute cholangitis: Diagnosis and management a b a,c A. Sokal , A. Sauvanet , B. Fantin , a,c,∗ V. de Lastours a Internal medicine unit, hôpital Beaujon, Assistance—publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, 92110 Clichy, France b Hepatic and pancreatic surgery unit, digestive disease center, hôpital Beaujon, Assistance—publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, 92110 Clichy, France c Inserm, IAME, UMR 1137, université Paris Diderot, 75018 Paris, France Available online 24 June 2019 KEYWORDS Summary Acute cholangitis is an infection of the bile and biliary tract which in most cases is the consequence of biliary tract obstruction. The two main causes are choledocholithiasis Acute cholangitis; Etiology; and neoplasia. Clinical diagnosis relies on Charcot’s triad (pain, fever, jaundice) but the insuf- Epidemiology; ficient sensitivity of the latter led to the introduction in 2007 of a new score validated by the Management Tokyo Guidelines, which includes biological and radiological data. In case of clinical suspicion, abdominal ultrasound quickly explores the biliary tract, but its diagnostic capacities are poor, especially in case of non-gallstone obstruction, as opposed to magnetic resonance cholangiopan- creatography and endoscopic ultrasound, of which the diagnostic capacities are excellent. CT scan is more widely available, with intermediate diagnostic capacities. Bacteriological sampling through blood cultures (positive in 40% of cases) and bile cultures is essential. A wide variety of bacteria are involved, but the main pathogens having been found are Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp., justifying first-line antimicrobial therapy by a third-generation cephalosporin. -

Recurrent Acute Pancreatitis Due to Haemobilia from a Hepatic Artery Aneurysm A

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.59.695.590 on 1 September 1983. Downloaded from Postgraduate Medical Journal (September 1983) 59, 590-592 Recurrent acute pancreatitis due to haemobilia from a hepatic artery aneurysm A. S. MEE J. A. MCM. TURNER M.D., M.R.C.P. M.R.C.P. N. MENZIES GOW F.R.C.S. Departments of Gastroenterology, Medicine and Surgery, Central Middlesex Hospital, Acton Lane, London NW10 Summary history of malaise, lethargy and anorexia and a 4-day A case of recurrent acute pancreatitis due to haemo- history of vomiting. Following one episode of vomit- bilia secondary to a bleeding hepatic artery aneurysm ing, she had brought up fresh blood clots. Two days is presented. Embolization of the hepatic artery before admission, she complained of a continuous resulted in cessation of bleeding and resolution of aching pain in the right hypochondrium which pancreatitis. persisted for 24 hr. On the was examination, patient well-nourished,by copyright. KEY WORDS: recurrent pancreatitis, haemobilia, hepatic artery pyrexial 38-2°C and jaundiced. The abdomen was aneurysm. soft with no palpable masses. Rectal examination showed no melaena. Introduction Investigations showed haemoglobin 12-3 g/dl, Haemobilia remains an uncommon cause of gas- white cell count 22-4 x 109/litre, erythrocyte sedimen- trointestinal haemorrhage. Trauma accounts for the tation rate 43 mm/hr, bilirubin 110 ,umol/litre, majority of cases although other causes are inflam- alanine aminotransferase 627 iu/litre (normal<35), matory (pyogenic and helminthic), cholelithiasis, aspartate aminotransferase 825 iu/litre (nor- vascular malformations, pancreatitis and neoplasms. -

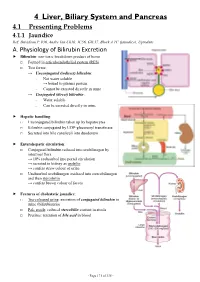

4 Liver, Biliary System and Pancreas 4.1 Presenting Problems 4.1.1 Jaundice Ref: Davidson P

4 Liver, Biliary System and Pancreas 4.1 Presenting Problems 4.1.1 Jaundice Ref: Davidson P. 936, Andre Tan Ch10, JC56, GIL17, Block A TC (jaundice), Uptodate A. Physiology of Bilirubin Excretion Bilirubin: non-toxic breakdown product of heme □ Formed in reticuloendothelial system (RES) □ Two forms: → Unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin: - Not water soluble → bound to plasma protein - Cannot be excreted directly in urine → Conjugated (direct) bilirubin: - Water soluble - Can be excreted directly in urine Hepatic handling: □ Unconjugated bilirubin taken up by hepatocytes □ Bilirubin conjugated by UDP-glucuronyl transferase □ Secreted into bile canaliculi into duodenum Enterohepatic circulation: □ Conjugated bilirubin reduced into urobilinogen by intestinal flora → 10% reabsorbed into portal circulation → secreted in kidney as urobilin → confers straw colour of urine □ Unabsorbed urobilinogen oxidized into stercobilinogen and then stercobilin → confers brown colour of faeces Features of cholestatic jaundice: □ Tea-coloured urine: excretion of conjugated bilirubin in urine (bilirubinuria) □ Pale stools: reduced stercobilin content in stools □ Pruritus: retention of bile acid in blood - Page 171 of 335 - B. Causes of Jaundice Pre-hepatic Hepatic Post-hepatic Suggestive - Lemon yellow jaundice - Yellow jaundice - Greenish jaundice features - Dark stools (↑stercobilin) - Normal stools - Pale stools - Normal urine - Tea-coloured urine - Tea-coloured urine - Pruritus ± scratch marks LFT - ↑unconj. bilirubin - ↑conj. bilirubin - ↑conj. Bilirubin -

Pseudosclerosing Cholangitis in Extrahepatic Portal Venous Obstruction 273

272 Gut, 1992, 33, 272-276 Pseudosclerosing cholangitis in extrahepatic portal venous obstruction Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.33.2.272 on 1 February 1992. Downloaded from J B Dilawari, Y K Chawla Abstract procedure and what we were looking for and Biliary changes secondary to portal advised that the ERCP findings would probably hypertension have rarely been described in have little bearing on their management. published reports. Twenty consecutive patients with extrahepatic portal venous obstruction, all of whom showed a variable SPLENOPORTOVENOGRAPHY degree of abnormalities in the biliary tract Percutaneous splenoportovenography was done suggestive of sclerosing cholangitis, are under fluoroscopic control using 40 ml ofConray described. These biliary abnormalities were: 420 (sodium iothalamate BP) by the standard focal narrowing, dilatations, and cholangitic technique5 (Fig 1). Six films at the rate of changes affecting the main bile ducts and 1/second were taken. Spontaneous splenorenal hepatic ducts. The left hepatic duct and its shunt was defined when contrast, injected into branches were affected in all patients. Only the splenic pulp, was seen entering the inferior one patient had clinical or biochemical vena cava through collaterals between the splenic evidence of cholestasis. The mechanism of and renal veins. these abnormalities in the biliary tract of these patients is perhaps the development of portal collaterals. SPLENIC PULP PRESSURE Splenic pulp pressure was measured using an electronic pressure recorder (Siemens mingo- There are only a few case reports of biliary graph) at the time of splenoportovenography. changes in patients with portal hypertension,'" and most are of patients with extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. -

Diseases of the Gall Bladder and Biliary Tract

Diseases of the gall-bladder and biliary tract based on www.harrisonsonline.com images.MD, Gallstones Grant Sanders, Andrew N Kingsnorth BMJ 2007;335:295-9 NEJM and and many others Dr. Fenyvesi Tamás 04/10/2017 11 „Become a doctor, no lectures required.” Saying Goodbye to Lectures in Medical School — Paradigm Shift or Passing Fad? Richard M. Schwartzstein, M.D., and David H. Roberts, M.D. NEJM 2017;377:605 2 Secretion of the bile in the. hepatic lobuli : ductuli---interlobular ducti—right and and left ductus hepaticus ; Here joins the ductus cysticus, The common ductus choledochus -ampulla Vateri-duodenum 33 44 . The bile is a pigmented isotonic fluid: water 82%,bile acids 12%, lecithin and other phospholipids 4%, Non esteric cholesterol 0,7%, etc ( ions, proteins, mucus,metabolites) 55 The primary bile acids : cholic- and chenodeoxicholic-acid derived from cholesterole and excreded in conjugation with glycin or taurin. They are detergents in watery solution, above 2mM concentration they form aggregates (micellum) 66 The enterohepatic circulation is a basic phenomenon Bile acids (b.a)are reabsorbed from the whole intestine in a passive way and actively from the jejunum Tha b.a.reserv is ~ 2-4g , 5-10 recirculations daily loss about 0.3-0.6g synthesis is being hinderd by reabsorbed b.a. ( 7 α-hydroxylase ) 77 . [email protected] 88 Function of the g.b. and of the Oddi sphincter The O.s. controlls the excretion of bile and stops reflux from the duodenum The g.b. function is controlled by cholecystokinin from duodenum mucosa (amino acids and fat…) g.b. -

Indications for Non‐Transplant Surgery in Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector HPB, 2005; 7: 292–297 Indications for non-transplant surgery in primary sclerosing cholangitis BASTIAN DOMAJNKO & STEVEN A. AHRENDT Department of Surgery, University of Rochester Medical School, Rochester, NY 14642, USA Abstract Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PCS) is a progressive disease leading to secondary biliary cirrhosis. Patients are at increased risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma, which is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage. Treatment of PCS includes medical therapy, endoscopic biliary dilation, percutaneous transhepatic stenting, extrahepatic biliary resection and liver transplantation. The most effective management of primary sclerosing cholangitis before the onset of cirrhosis remains unclear. Non-transplant surgical procedures have a limited but defined role in patients with PCS. Resection of the extrahepatic biliary tree in symptomatic non-cirrhotic patients improves hyperbilirubinaemia and prolongs both transplant- free and overall survival when compared with non-operative dilation and/or stenting. Surgical resection may also definitively establish or exclude a diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with dominant extrahepatic or perihilar strictures. Extrahepatic bile duct resection may also reduce the risk of cholangiocarcinoma. Extrahepatic biliary resection should be considered in selected non-cirrhotic patients with symptomatic biliary obstruction and dominant extrahepatic and/or perihilar strictures. Those