What Happens When Local Phone Service Is Deregulated? Early Returns Suggest Liberalization Benefits Consumers Just As Long Distance Deregulation Did

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tds National Reports Itu Telecom World 2003 and Canton Ofgeneva Hosted by Therepublic

2003 ORLD W ELECOM TDS NATIONAL REPORTS TDS NATIONAL International Telecommunication Union Place des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 20, Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 730 6161 – Fax: +41 22 730 6444 E-mail: [email protected] TDS NATIONAL REPORTS TDS NATIONAL ITU T HOSTED BY THE REPUBLIC www.itu.int/itutelecom AND CANTON OF GENEVA TDS NATIONAL REPORTS The Republic and Canton of Geneva sponsors of the Telecom Development Symposium (TDS) Table of contents Page Page Albania ................................................. 1 Moldova................................................ 145 Angola .................................................. 5 Mongolia............................................... 147 Armenia................................................ 9 Myanmar .............................................. 155 Bangladesh .......................................... 11 Nepal .................................................... 159 Benin .................................................... 17 Nicaragua ............................................. 165 Bhutan.................................................. 21 Pakistan................................................ 167 Bosnia and Herzegovina ...................... 27 Papua New Guinea .............................. 179 Burkina Faso ........................................ 31 Paraguay .............................................. 183 Burundi................................................. 41 Cambodia............................................. 43 Peru ................................................... -

Trends in Telephone Service

Trends in Telephone Service Industry Analysis Division Common Carrier Bureau August 2001 This report is available for reference in the FCC’s Information Center at 445 12th Street, S.W., Courtyard Level. Copies may be purchased by calling International Transcription Service, Inc. at (202) 857-3800. The report can also be downloaded [file names: TREND101.ZIP, TREND101.PDF] from the FCC-State Link Internet site at <www.fcc.gov/ccb/stats>. Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................. 1-1 Access Charges ............................................................................................ 1-3 Table 1.1 Interstate Per-Line Access Charges ..........................................................................1-5 Table 1.2 Interstate Per-Minute Access Charges ......................................................................1-6 Table 1.3 Interstate Per-Line Access Charges by Carrier..........................................................1-7 Table 1.4 Interstate Per-Minute Access Charges by Carrier......................................................1-8 Advanced Telecommunications.................................................................... 2-1 Table 2.1 High-Speed Lines.....................................................................................................2-3 Table 2.2 Advanced Services Lines..........................................................................................2-3 Table 2.3 Residential and Small Business -

Telecommunications Provider Locator

Telecommunications Provider Locator Industry Analysis & Technology Division Wireline Competition Bureau January 2010 This report is available for reference in the FCC’s Information Center at 445 12th Street, S.W., Courtyard Level. Copies may be purchased by contacting Best Copy and Printing, Inc., Portals II, 445 12th Street S.W., Room CY-B402, Washington, D.C. 20554, telephone 800-378-3160, facsimile 202-488-5563, or via e-mail at [email protected]. This report can be downloaded and interactively searched on the Wireline Competition Bureau Statistical Reports Internet site located at www.fcc.gov/wcb/iatd/locator.html. Telecommunications Provider Locator This report lists the contact information, primary telecommunications business and service(s) offered by 6,493 telecommunications providers. The last report was released March 13, 2009.1 The information in this report is drawn from providers’ Telecommunications Reporting Worksheets (FCC Form 499-A). It can be used by customers to identify and locate telecommunications providers, by telecommunications providers to identify and locate others in the industry, and by equipment vendors to identify potential customers. Virtually all providers of telecommunications must file FCC Form 499-A each year.2 These forms are not filed with the FCC but rather with the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), which serves as the data collection agent. The pool of filers contained in this edition consists of companies that operated and collected revenue during 2007, as well as new companies that file the form to fulfill the Commission’s registration requirement.3 Information from filings received by USAC after October 13, 2008, and from filings that were incomplete has been excluded from this report. -

CODE of COLORADO REGULATIONS 4 CCR 723-2 Public Utilities Commission

DEPARTMENT OF REGULATORY AGENCIES Public Utilities Commission RULES REGULATING TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES AND PROVIDERS OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES 4 CCR 723-2 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] _________________________________________________________________________ BASIS, PURPOSE, AND STATUTORY AUTHORITY The basis and purpose of these rules is generally to implement, administer and enforce the telecommunications provisions of Title 40 of the Colorado Revised Statutes; and regulate telecommunications proceedings and regulatory activities before the Commission. These rules address a wide variety of subject areas. Therefore, specific statements of Basis, Purpose, and Statutory Authority are found at the beginning of each subchapter of these rules. The statutory authority for the promulgation of these rules is found at §§ 29-11-106(3); 38-5.5-101; 39-32- 104; 40-2-108; 40-3-101; 40-3-102; 40-3-103; 40-3-107; 40-3-110; 40-3.4-106; 40-4-101; 40-7-113.5; 40- 7-116.5; 40-15-101; 40-15-108(2); 40-15-109(3); 40-15-201; 40-15-203.5; 40-15-208(2)(a); 40-15-301; 40-15-302(1)(a) and (2); 40-15-302.5; 40-15-305; 40-15-404; 40-15-502(1), (3)(a), and (5)(b); 40-15-503; 40-17-103(2) and (3), C.R.S. GENERAL PROVISIONS 2000. Scope and Applicability. Rules 2000 through 2099 are rules of general applicability to be applied consistent with Commission jurisdiction and rules 2100 through 2999. More specific applicability provisions are found in the various subchapters of this Part 2. -

AT&T Small Business System Speakerphone with Intercom And

974CIB_(Rev11-12)ml24.05.06 5/24/06 9:29 PM Page II USER’S MANUAL Part 2 AT&T Small Business System Speakerphone with Intercom and Caller ID/Call Waiting 974 For Customer Service Or Product Please also read Information, Visit Our Web Site At Part 1 — Important www.telephones.att.com product information © 2006 Advanced American Telephones. All rights reserved. AT&T and the Globe Design are trademarks of AT&T Corp., licensed to Advanced American Telephones. 974CIB_(Rev11-12)ml24.05.06 5/24/06 9:29 PM Page III 974CIB_(Rev11-12)ml24.05.06 5/24/06 9:29 PM Page i Contents Product overview ........................... 1 Assign the line group for this phone ....................................... 39 Before you begin............................. 2 Parts list.................................................. 2 Erase all settings and return the phone to default settings..... 40 Tools needed......................................... 2 Set this phone to be the DSL users............................................... 4 Centrex console phone .............. 41 Glossary ................................................. 5 Set the Centrex console Programmable features list ............... 7 delayed ring time........................... 42 Contents Contents Audible signals.................................... 10 Set the display language................... 42 Installation ....................................... 11 Telephone operation...................... 43 Battery installation............................ 11 Make or answer a call...................... 43 Table/desk -

Telecom Customer Choice Overview

CUSTOMER CHOICE & LOCAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES IN DC Prepared: January 31, 2016 DC Residential Customers’ Local Telephone Service Choices as of January 2016 DC Residential Customers’ Local Telephone Service Choices as of January 2016 Local Exchange Service . Access Point, Inc.* . ACN Communication Services, Inc.* . Broadview Networks, Inc.* . Matrix Telecom, Inc. d/b/a Matrix Business Technologies d/b/a/ Trinsic* . Metropolitan Telecommunications of DC, Inc. (MetTel)* . Starpower Communications, LLC - d/b/a RCN* . Verizon Washington, DC Inc.* * Had residential customers as of January 2016 DC Residential Customers’ Local Telephone Service Choices as of January 2016 (Continued) • Wireless or Cellular (Bundles local and long distance) (Not tariffed at the DCPSC) • Pay Telephones • Phone cards • Voice over IP (Internet Protocol) Telephony (Not tariffed at DCPSC) -- AT&T, Verizon, Vonage • Voice Over Cable (Not tariffed at DCPSC) -- Comcast Residential Local Service Provider Options as of January 2016 Local Service & No Local Service – Local & Long Other Packages Custom Calling Packaged with Distance Packages (Combinations of Features Custom Calling voice, Internet, Features cable, and TV) Access Point, Inc. Verizon ACN Communication Comcast (not regulated Services, Inc. by PSC) ACN Communication Starpower Starpower Cavalier Telephone Services, Inc. Communications, Communications, Mid-Atlantic, L.L.C. LLC - d/b/a RCN LLC - d/b/a RCN Broadview Networks, Matrix Telecom, Inc. Starpower Inc. d/b/a Matrix Business Communications, LLC Technologies d/b/a/ - d/b/a RCN Trinsic Metropolitan Verizon Verizon FIOS (not Telecommunications of regulated by PSC) DC, Inc. (MetTel) Verizon Vonage (long distance and International, not regulated by PSC) Monthly Residential Telephone Prices in D.C. -

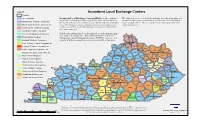

Incumbent Local Exchange Carriers

Legend Incumbent Local Exchange Carriers Counties AT&T Kentucky Incumbent Local Exchange Carriers (ILECs) are the companies The colored areas are based on the exchange area, the geographic area originally franchised by the Kentucky Public Service Commission as in which telephone prices and services are the same for an incumbent Ballard Rural Telephone Cooperative the sole provider of local telephone service within a specific geographic local exchange carrier. These areas do not necessarily coincide with Brandenburg Telephone Company, Inc. area. This map shows those companies that were providing service county boundaries. Cincinnati Bell Telephone Company on the effective date of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 or their successor companies. Coalfields Telephone Company Duo County Telephone Cooperative Now that the industry has been deregulated, several companies may offer service in a single area. New ones entering the market are Boone Foothills Rural Telephone Competitive Local Exchange Carriers (CLECs) , which are not Kenton Campbell Highland Telephone Cooperative associated with a geographic area and are not shown on this map. Cincinnati Leslie County Telephone Company, Inc. Gallatin Bell Pendleton Bracken Lewisport Telephone Company, Inc. Carroll Trimble Grant Mason Greenup Logan Telephone Cooperative, Inc. Owen Robertson Lewis Henry Harrison Mountain Telephone Cooperative, Inc. Windstream KY E Boyd Oldham Fleming Carter North Central Telephone AT&T Kentucky Scott Nicholas Shelby Franklin Bourbon Rowan Peoples Rural Telephone Jefferson -

Telecommunications Competition Survey for Retail Local Voice Services, Describing the Confidentiality Procedures the Board Would Apply to the Survey Responses

TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMPETITION SURVEY FOR RETAIL LOCAL VOICE SERVICES IN IOWA A Report of the Iowa Utilities Board Diane Munns, Chair Mark Lambert Elliott Smith January 2004 TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMPETITION SURVEY FOR RETAIL LOCAL VOICE SERVICES A Report of the Iowa Utilities Board IUB Project Manager: Larry M. Stevens Utility Specialist – Policy Development (515) 281-4725 [email protected] Iowa Utilities Board 350 Maple Street Des Moines, IA 50319 January 2004 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Executive Summary ..................................................................................... v List of Acronyms and Definitions ................................................................ix I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 1 A. Purpose and Design of the Study .......................................... 1 1. Retail Local Service Connections……………………………. 1 2. Retail Pricing Information…………………………………….... 2 3. Advertising Information……………………………………….... 2 4. Confidential Information……………………………………….. 3 5. The Survey Process………………………………………….. 3 6. Verification of Survey Responses…………………………….. 4 B. Background of Telecommunications Regulation in Iowa .... 4 1. Different Carriers Are Subject to Different Regulation…...... 4 2. Deregulation of Competitive Services……………………….. 6 C. Description of Relevant Federal Laws……………………….. .8 1. The Telecommunications Act of 1996………………………... 8 2. Pending FCC Actions………………………………...... ………9 II. DESCRIPTIONS OF POTENTIAL ALTERNATIVES ....................... -

UNITED TELEPHONE COMPANY of OHIO D/B/A CENTURYLINK

UNITED TELEPHONE COMPANY OF OHIO d/b/a CENTURYLINK LOCAL TERMS OF SERVICE FOR NON-BASIC LOCAL EXCHANGE SERVICES (INCLUDING TIER 2 BUSINESS SERVICES) AND MESSAGE TOLL TELEPHONE (LOCAL TOLL) SERVICE* Applying in all exchanges of the Company See Terms and Conditions for Business Products and Services for descriptions, terms and conditions governing additional de-tariffed business service not included herein. Rates and charges for all services contained herein may be found in the United Telephone Company of Ohio d/b/a CenturyLink Price List for De-Tariffed Non-BLES and Message Toll Telephone (Local Toll) Services *Referred to hereafter as MTS Page 1 June 20, 2016 OH 16-07 UNITED TELEPHONE COMPANY OF OHIO d/b/a CENTURYLINK LOCAL TERMS OF SERVICE FOR NON-BASIC LOCAL EXCHANGE SERVICES AND MTS INDEX Section Page Local Exchange General Regulations 2 Exchange Areas 4 Local Measured Service 41 Extended Local Calling Service 43 General Regulations 44 Explanation of Terms 56 Directory Listings 68 Directory Assistance (Residence and Business) 77 Advance Payments and Deposits 81 Service Connections, Changes and Moves 82 Circuit Miles and Zones 85 Key Telephone Systems 85 Private Branch Exchange Service 86 Toll Recording Trunks 86 Connection with Certain Facilities Provided by Subscribers 87 Special Equipment or Assemblages of Equipment 110 Temporary Suspension of Service (Vacation Service) 113 Termination of Service 114 Supplemental Equipment 116 Custom Calling Service 118 Call Line Identifier 124 Call Blocking and Screening Services 126 ExpressTouch -

Public Utility Commission of Texas Page 1 of 54 Substantive Rules

PUBLIC UTILITY COMMISSION OF TEXAS PAGE 1 OF 54 SUBSTANTIVE RULES. CHAPTER 26. TELECOMMUNICATIONS. The Public Utility Commission of Texas (commission) adopts an amendment to §26.5, relating to Definitions, with changes to the proposed text as published in the May 19, 2000, Texas Register (25 TexReg 4423). The amendment incorporates changes and additions required as a result of rulemakings in Project Number 21155, Rulemaking to Implement PURA Chapter 58 Provisions Relating to Customer Specific Contracts, Packaging Flexibility and Promotional Offerings; Project Number 21156, Rulemaking to Implement PURA Chapter 58 Provisions Relating to Withdrawal of Election, Rate Caps and Rate Adjustments, Packaging Flexibility and Pricing for Non-Basic Services; and Project Number 21161, Rulemaking to Establish Process for New Services and Promotional Offerings, Pricing and Packaging Flexibility Tariffs Pursuant to PURA Chapters 52, 58 and 59. This amendment, through the aforementioned integration, is necessary to provide continuity with the provisions implemented by the 76th Legislature in Senate Bill 560 and the Public Utility Regulatory Act (PURA). This amendment was adopted under Project Number 21169. Project Number 21169 also is being employed to make changes to the commission's substantive rules related to Senate Bill 560. The amendment also (1) removes references to Chapter 23 as a result of the commission's reorganization of its rules and the move of the telecommunications-related substantive rules to Chapter 26, and (2) modifies the definition of the term "electric utility" to comply with the new definition of PUBLIC UTILITY COMMISSION OF TEXAS PAGE 2 OF 54 SUBSTANTIVE RULES. CHAPTER 26. TELECOMMUNICATIONS. electric utility in PURA and the commission's rules in Chapter 25, Substantive Rules Applicable to Electric Service Providers. -

Phone Handbook

THE PHONE HANDBOOK From the Office of the Minnesota Attorney General helping people afford their lives and live with dignity and respect www.ag.state.mn.us Table of Contents Local Service ............................................................................................... 3 Do I Have a Choice for My Local Telephone Service? .............................................................................................. 3 What is the Cost of Local Phone Service? ................................................................................................................ 3 How Can I Reduce the Price of My Local Phone Bill? .............................................................................................. 4 What are the Charges on My Telephone Bill and are They Required?..................................................................... 4 Is Inside Wire Insurance A Good Deal? ..................................................................................................................... 5 How Can I Prevent Disconnection of My Phone Service? ....................................................................................... 5 Is There Any Assistance Available to Help Pay for My Telephone Service? ........................................................... 5 Telephone Service for the Communication Impaired .............................................................................................. 6 What if There is a Delay In Obtaining My Telephone Service? ............................................................................... -

Basic Questions About Telephone Service

Basic Questions about Telephone Service What's the difference What's the difference between wireline and wireless telephone service? between wireline and wireless telephone Wireline service means the telephone is connected to the telephone company's facilities by use of a wire. This includes portable and cordless service? phones because their base connects into the facilities. Wireline service is also known as landline service. Wireless service covers cell phones and other devices that use radio waves to transmit voice, text messages, and data through the company's facilities. What is the difference What is the difference between local service and long distance service between local service and provided by wireline telephone companies? long distance service? Local telephone service allows you to make and to receive telephone calls. The monthly service charge also covers calls that occur to places near you. Your telephone company may provide your local service at a flat rate per month. Some telephone companies also offer measured local service, which could include a set number of minutes or calls per month, and if you exceed that allowance, you may be billed, per call or per minute. Calls placed to locations outside your local service area may be billed, depending on the location or distance. They may be referred to as local toll or long distance calls. You can choose to have your local telephone company provide your local toll call service, or you can obtain it from another company. You can choose which company to provide your long distance service. You can also select no company, if you choose not to have long distance service.