Chapter 4: Culture and Tradition As a Development Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kingdom of Bhutan Health System Review

Health Sy Health Systems in Transition Vol. 7 No. 2 2017 s t ems in T r ansition Vol. 7 No. 2 2017 The Kingdom of Bhutan Health System Review The Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (the APO) is a collaborative partnership of interested governments, international agencies, The Kingdom of Bhutan Health System Review foundations, and researchers that promotes evidence-informed health systems policy regionally and in all countries in the Asia Pacific region. The APO collaboratively identifies priority health system issues across the Asia Pacific region; develops and synthesizes relevant research to support and inform countries' evidence-based policy development; and builds country and regional health systems research and evidence-informed policy capacity. ISBN-13 978 92 9022 584 3 Health Systems in Transition Vol. 7 No. 2 2017 The Kingdom of Bhutan Health System Review Written by: Sangay Thinley: Ex-Health Secretary, Ex-Director, WHO Pandup Tshering: Director General, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Health Kinzang Wangmo: Senior Planning Officer, Policy and Planning Division, Ministry of Health Namgay Wangchuk: Chief Human Resource Officer, Human Resource Division, Ministry of Health Tandin Dorji: Chief Programme Officer, Health Care and Diagnostic Division, Ministry of Health Tashi Tobgay: Director, Human Resource and Planning, Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan Jayendra Sharma: Senior Planning Officer, Policy and Planning Division, Ministry of Health Edited by: Walaiporn Patcharanarumol: International Health Policy Program, Thailand Viroj Tangcharoensathien: International Health Policy Program, Thailand Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies i World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. The Kingdom of Bhutan health system review. -

Bhutan's Political Transition –

Spotlight South Asia Paper Nr. 2: Bhutan’s Political Transition – Between Ethnic Conflict and Democracy Author: Dr. Siegried Wolf (Heidelberg) ISSN 2195-2787 1 SSA ist eine regelmäßig erscheinende Analyse- Reihe mit einem Fokus auf aktuelle politische Ereignisse und Situationen Südasien betreffend. Die Reihe soll Einblicke schaffen, Situationen erklären und Politikempfehlungen geben. SSA is a frequently published analysis series with a focus on current political events and situations concerning South Asia. The series should present insights, explain situations and give policy recommendations. APSA (Angewandte Politikwissenschaft Südasiens) ist ein auf Forschungsförderung und wissenschaftliche Beratung ausgelegter Stiftungsfonds im Bereich der Politikwissenschaft Südasiens. APSA (Applied Political Science of South Asia) is a foundation aiming at promoting science and scientific consultancy in the realm of political science of South Asia. Die Meinungen in dieser Ausgabe sind einzig die der Autoren und werden sich nicht von APSA zu eigen gemacht. The views expressed in this paper are solely the views of the authors and are not in any way owned by APSA. Impressum: APSA Im Neuehnheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg [email protected] www.apsa.info 2 Acknowledgment: The author is grateful to the South Asia Democratic Forum (SADF), Brussels for the extended support on this report. 3 Bhutan ’ s Political Transition – Between Ethnic Conflict and Democracy Until recently Bhutan (Drukyul - Land of the Thunder Dragon) did not fit into the story of the global triumph of democracy. Not only the way it came into existence but also the manner in which it was interpreted made the process of democratization exceptional. As a land- locked country which is bordered on the north by Tibet in China and on the south by the Indian states Sikkim, West Bengal, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, it was a late starter in the process of state-building. -

GE.06-65882 19 December 2006 ENGLISH/RUSSIAN ONLY UNITED

19 December 2006 ENGLISH/RUSSIAN ONLY UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION TO COMBAT DESERTIFICATION COMMITTEE FOR THE REVIEW OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CONVENTION Fifth session Buenos Aires, 12–21 March 2007 REVIEW OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CONVENTION AND OF ITS INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS, PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 22, PARAGRAPH 2 (a) AND (b), AND ARTICLE 26 OF THE CONVENTION, AS WELL AS DECISION 1/COP.5, PARAGRAPH 10 REVIEW OF THE REPORTS ON IMPLEMENTATION OF AFFECTED COUNTRY PARTIES OF REGIONS OTHER THAN AFRICA, INCLUDING ON THE PARTICIPATORY PROCESS, AND ON EXPERIENCE GAINED AND RESULTS ACHIEVED IN THE PREPARATION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF ACTION PROGRAMMES Compilation of summaries of reports submitted by affected Asian country Parties 1. In accordance with decision 9/COP.7, the Committee for the Review of the Implementation of the Convention at its fifth session will review the reports on implementation of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification by affected country Parties of regions other than Africa, including Asia and the Pacific. By its decision 11/COP.1, the Conference of the Parties requested the secretariat to compile summaries of such reports. Decision 11/COP.1 also defined the format and content of reports and, in particular, required summaries not to exceed six pages. 2. This document contains 31 narrative summaries of reports as submitted by affected Asian country Parties as at 17 November 2006, and document ICCD/CRIC(5)/MISC.1/Add.1 contains 26 tabular summaries; these are reproduced without formal editing. The secretariat has also made these reports available in their entirety on its website <www.unccd.int>. -

Governing Bodies

Section 1 Governing Bodies 1 Governing Bodies The Fifty-first World Health Assembly, held in Geneva from World Health 11 to 15 May 1998, elected Dr Faisal Radhi Al-Mousawi Assembly (Bahrain) as President, Mr J.Y. Thinley (Bhutan) as one of the Vice-Presidents, and Dr Nimal Seripala de Silva (Sri Lanka) as Chairman of Committee B. Bangladesh was elected to designate a person to serve as a Member of the Executive Board for a term of three years, to fill the vacancy created by one of the outgoing Members (Bhutan) from the South-East Asia Region on completion of its term. The Assembly appointed Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland as the Director-General of the Organization for a five-year term beginning 21 July 1998. It also debated the issue of regional allocations and adopted resolution WHA51.31. This resulted in a consensus for a compromise approach, which is substantially more favourable to the South-East Asia Region when compared with the earlier Executive Board proposal. The Fifty-second World Health Assembly was held in Geneva from 17 to 25 May 1999. The Assembly elected Mrs Maria de Belem Roseira (Portugal) as President. Mr S.U. Yussuf (Bangladesh) was elected as one of the Vice-Presidents and Dasho Sangay Ngedup (Bhutan) as one of the Vice-Chairmen of The Work of WHO in SEA 1 Committee B. In addition, delegates from Bangladesh and Myanmar from SEA Region were included in the Committee on Nominations. India was elected to designate a person to serve as a Member of the Executive Board for a term of three years, to fill the vacancy created by one of the outgoing Members (Indonesia) from the South-East Asia Region on completion of its term. -

Harald N. Nestroy, German Ambassador (Rtd.)

Harald N. Nestroy, German Ambassador (rtd.) Executive Chairman of “Pro Bhutan, Germany” Curriculum vitae and relations with Bhutan (January 2011) 1) CV Born : 1. February, 1938 in Breslau, Germany Married to Angelika J. Nestroy in Bhutan 14th November 1999 1957- 1963: Studies of Law at University of Mainz, Germany, and Barcelona, Spain. 1963 : First state diploma in Law 1964-1967 : School of Diplomacy, German Foreign Ministry, Bonn 1967-1968 : Member of the cabinet of Foreign Minister Willy Brandt 1968-1971 : German Embassy New Delhi, India : political officer 1971-1974 : German Embassy Bogota, Colombia: cultural attaché 1974-1977 : Foreign Ministry Bonn : Latin America desk 1977-1979 : Foreign Ministry Bonn : head of office “Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief” of the German Government 1979-1982 : German Ambassador in Congo 1982-1985 : German Consul General at Atlanta, Georgia for the South East of the USA. 1985-1989 : German Ambassador to Costa Rica, Central America 1989-1994 : Foreign Ministry Bonn : Political Dpt., head of desk for Western Neighbors of Germany 1994-1998 : German Ambassador to Malaysia 1998-2003 : German Ambassador to Namibia. 2009: The Cross 1. Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany was bestowed on Ambassador Nestroy by H.E. the President of the Federal Republic of Germany - 2 - 2 2) Relations of Ambassador Harald N. Nestroy with Bhutan: 1987 1st visit to Bhutan. 1992 2nd visit to Bhutan : * Preparation of Punakha Hospital project. * Received in private audience by H.M. the King of Bhutan. 1993 3rd visit to Bhutan : Signing of agreement with RGOB for construction of Punakha Hospital 1994 4th visit to Bhutan : laying of foundation stone for Punakha hospital. -

Portrait of a Leader

Portrait of a Leader Portrait of a Leader Through the Looking-Glass of His Majesty’s Decrees Mieko Nishimizu The Centre for Bhutan Studies Portrait of a Leader Through the Looking-Glass of His Majesty’s Decrees Copyright © The Centre for Bhutan Studies, 2008 First Published 2008 ISBN 99936-14-43-2 The Centre for Bhutan Studies Post Box No. 1111 Thimphu, Bhutan Phone: 975-2-321005, 321111,335870, 335871, 335872 Fax: 975-2-321001 e-mail: [email protected] www.bhutanstudies.org.bt To Three Precious Jewels of the Thunder Dragon, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck, Druk Gyalpo IV, His Majesty Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, Druk Gyalpo V and The People of Bhutan, of whom Druk Gyalpo IV has said, “In Bhutan, whether it is the external fence or the internal wealth, it is our people.” The Author of Gross National Happiness, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the Fourth Druk Gyalpo of the Royal Kingdom of Bhutan CONTENTS Preface xi 2 ENVISIONING THE FUTURE 1 To the Director of Health 6 2 To Special Commission 7 3 To Punakha Dratshang 8 4 To the Thrompon, Thimphu City Corporation 9 5 To the Planning Commission 10 6 To the Dzongdas, Gups, Chimis and the People 13 7 To the Home Minister 15 18 JUSTICE BORN OF HUMILITY 8 Kadoen Ghapa (Charter C, issued to the Judiciary) 22 9 Kadoen Ghapa Ka (Charter C.a, issued to the Judiciary) 25 10 Kadoen Ngapa (Chapter 5, issued to the Judiciary) 28 11 Charter pertaining to land 30 12 Charter (issued to Tshering) 31 13 To the Judges of High Court 33 14 To the Home Minister 36 15 Appointment of the Judges 37 16 To -

The University of Reading Forest Policy and Income Opportunities

The University of Reading International and Rural Development Department PhD Thesis Forest Policy and Income Opportunities from NTFP Commercialisation in Bhutan PHUNTSHO NAMGYEL Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy MAY 2005 Declaration I confirm that this is my own work and the use of all materials from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged. …………..……………………… Phuntsho Namgyel May 2005 DEDICATION TO THE KING, COUNTRY AND PEOPLE OF BHUTAN Acknowledgement Studying for a PhD is a demanding enterprise of time, funding and emotion. I am therefore indebted to a large number of people and agencies. Firstly, I am most grateful to the Royal Government of Bhutan for granting me a long leave of absence from work. In the Ministry of Agriculture where I work, I am most thankful to Lyonpo (Dr.) Kinzang Dorji, former Minister; Dasho Sangay Thinley, Secretary; and Dr. Pema Choephyel, Director. I also remain most thankful to Lyonpo Sangay Ngedup, Minister for his good wishes and personal interest in the research topic. With the war cry of ‘Walking the Extra Mile’, the Minister is all out to bring about a major transformation in rural life in the country. I look forward to being a part of the exciting time ahead in rural development in Bhutan. I have also received much support from Lyonpo (Dr.) Jigme Singay, Minister for Health, when the Minister was then Secretary, Royal Civil Service Commission. His Lordship Chief Justice Lyonpo Sonam Tobgye has been a source of great inspiration, support and information. I remain much indebted to the two Lyonpos. -

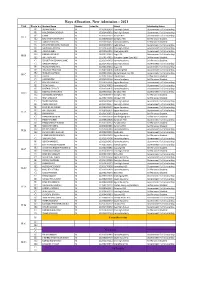

First Year Hostel Allocation 2021-Final

Boys Allocation, New Admission - 2021 Unit Room no. Student Name Gender Index No School Scholarship Status B1 SONAM DORJI M 12201400402 Desi High School Government Full Scholarship B1 KINLEY PEMA DENDUP M 12201400031 Desi High School Government Full Scholarship B2 JIGME M 12201210129 Jampel HSS Government Full Scholarship H1A B2 BAL KRISHNA SAPKOTA M 12200080102 Gelephu HSS Self Financed Student C1 TANDIN YOEDZER M 12201390412 Karma Academy Self Financed Student C1 PHUNTSHO NORBU WANGDI M 12201500242 Kelki School Government Full Scholarship B1 MONASH GURUNG M 12191400080 Desi High School Government Full Scholarship B1 ARJUN SUBBA M 12200360001 Drukjegang HSS Government Full Scholarship B2 KARMA LHENDUP M 12200330023 Daga HSS Government Full Scholarship H1B B2 ANIL GURUNG M 12190270025 Gongzim Ugyen Dorji HSS Self Financed Student C1 TSHULTRIM SONAM JURME M 12201390462 Karma Academy Self Financed Student C1 GANESH RASAILY M 12201400190 Desi High School Government Full Scholarship B1 TULASI RAM DAHAL M 12200330034 Daga HSS Government Full Scholarship B1 TIKA RAM PRADHAN M 12200930096 Dashiding HSS Government Full Scholarship B2 THINLEY JAMTSHO M 12200110149 Jigme Sherubling HSS Government Full Scholarship H1C B2 UGYEN M 12200190062 Lhuntse HSS Self Financed Student C1 UGYEN DORJI M 12201390416 Karma Academy Self Financed Student C1 KINLEY TSHERING M 12200260438 Ugyen Academy Government Full Scholarship B1 TASHI DAWA M 12201170053 Karmaling HSS Government Full Scholarship B1 KINZANG THINLEY M 12201390405 Karma Academy Government Full Scholarship -

Tiger Action Plan

TIGER ACTION PLAN FOR THE KINGDOM OF BHUTAN 2006-2015 Nature Conservation Division Department of Forests Ministry of Agriculture Royal Government of Bhutan In collaboration with WWF Bhutan Program TIGER ACTION PLAN FOR THE KINGDOM OF BHUTAN 2006-2015 Nature Conservation Division Department of Forests Ministry of Agriculture Royal Government of Bhutan In collaboration with WWF Bhutan Program Save The Tiger Fund Compiled by: Tiger Sangay Tshewang Wangchuk © 2005 Nature Conservation Division Department of Forests Ministry of Agriculture Royal Government of Bhutan ISBN 99936-666-0-2 CONTENTS Foreword by His Excellency, Lyonpo Sangay Ngedup Minister of Agriculture, Royal Government of Bhutan v Acknowledgement vi Executive Summary vii 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. STATUS OF TIGER CONSERVATION IN BHUTAN 3 2.1. Tiger Conservation Program 3 2.2. Tiger Population and Distribution 5 2.3. National and Global Significance 5 3. OPPORTUNITIES 8 3.1. Extensive Habitat 8 3.2. Legislation 9 3.3. Inaccessible Habitat and Wide Tiger Distribution 9 3.4. Pro-conservation Development Strategy and Stable Political Conditions 9 4 KEY THREATS 10 4.1. Commercial Poaching and Wildlife Trade 10 4.2. Fragmentation of Habitat 10 4.3. Reconciling Tiger Conservation And Human Needs 11 4.4. Lack of Public Awareness on Tiger Conservation Issues 12 4.5. Inadequate Database and Data Management 13 4.6. Lack of Trained Manpower 13 5. ACTION PLAN 14 5.1. Goal 15 5.2. Objectives 15 A. Species Conservation 16 B. Habitat Conservation 18 C. Human Wildlife Conflict Management 20 D. Education and Awareness Program 22 E. Regional Cooperation 22 F. -

76Th Session.Pdf

TRANSLATION OF THE PROCEEDINGS AND RESOLUTIONS OF THE 76TH SESSION OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF BHUTAN HELD FROM THE FIFTH DAY OF THE FIFTH MONTH TO THE SEVENTH DAY OF THE SIXTH MONTH OF THE MALE EARTH TIGER YEAR (JUNE 29TH TO JULY 30TH, 1998) I. OPENING CEREMONY The 76th Session of the National Assembly of Bhutan commenced on the Fifth Day of the auspicious Fifth Month of the Male Earth Tiger Year corresponding to 29th June 1998 with the arrival of His Majesty the King in the traditional Chipdrel ceremony followed by the performance of the auspicious Zhugdrel Phunsum Tsogpai Tendrel. In his opening address, the Speaker of the National Assembly, Dasho Kinzang Dorji, welcomed His Majesty the King, the representatives of the Dratshang and Rabdeys, the government representatives, people’s representatives (Chimis) and the candidates who had come from the Dzongkhags for the election of six new Royal Advisory Councillors. The Speaker also extended a warm Tashi Delek and welcomed the new Chimis and representatives of the Dratshang and the government. He reminded them of their important responsibilities as members of the National Assembly and emphasized the need for them to participate sincerely and thoughtfully in the decision-making process of the country. The Speaker informed the members that despite a late start on the path of modern development, Bhutan is today regarded as a ‘success story’, a country that has developed and achieved remarkable success within a very short span of time. Bhutan had achieved unprecedented development and progress without eroding the values of its age-old culture and traditions. -

BA Sociology & Political Science 2021

BA Sociology & Political Science 2021 Merit List of Registered Candidates for In-Country RGoB Scholarships to RTC for 2021 (B.A Sociology & Political SCIs (Min. 55% in English with 50% each in three best subject) Sex CID COM Name School Stream MATHS SUMTAG ENGLISH HISTORY PHYSICS BIOLOGY NYENCHA Merit Rank NYENGAG Total Marks Total CHOEDJUK DZONGKHA CHEMISTRY ECONOMICS GEOGRAPHY Index Number VISUAL ARTS VISUAL AGRICULTURE MEDIA STUDIES MEDIA ACCOUNTANCY Total Ranking Point Total ENVIRONMENT SCI Application Number COMPUTER STUDIES DZONGKHA RIZHUNG DZONGKHA BUSINESS MATHEMATICS 1 941_2104S02065 Seisa Kokusai High School Nidup Dorji M 11504002968 SCI 94 93 93 94 90 374 464 2 941_2104S00858 12200060042 DAMPHU CS Kelden Ghalay M 11202005418 SCI 97 94 77 82 97 370 447 3 941_2104S01101 12200060013 DAMPHU CS Norbu Tshering SamdrupM 11109002476 SCI 92 93 81 75 100 360 441 4 941_2104S00311 12200020001 YANGCHENPHUG HSS Rekha Chhetri F 11203002997 SCI 89 93 93 73 83 91 360 522 5 941_2104S01723 12200210070 RANJUNG CS Tshering Dekar F 11513002665 COM 88 85 80 86 98 93 359 530 6 941_2104S00400 12200260084 UGYEN ACADEMY HSS Tashi Rabten M 11108001278 SCI 94 93 81 73 98 358 439 7 941_2104S00461 12200260051 UGYEN ACADEMY HSS Divya Nepal F 11306001086 SCI 85 96 94 68 72 94 356 509 8 941_2104S01060 12200060016 DAMPHU CS Sisir Pokhrel M 11805003584 SCI 91 95 72 76 93 355 427 9 941_2104S02838 12200210010 RANJUNG CS Sonam Norbu M 11509004845 SCI 93 89 85 75 97 354 439 10 941_2104S00591 12201390024 KARMA ACADEMY Kinzang Lhaden F 11705002292 SCI 92 93 80 72 97 -

1 Father Estevao Cacella's Report on Bhutan in 1627

FATHER ESTEVAO CACELLA'S REPORT ON BHUTAN IN 1627 Luiza Maria Baillie** Abstract The article introduces a translation of the account written in 1627 by the Jesuit priest Father Estevao Cacella, of his journey with his companion Father Joao Cabral, first through Bengal and then through Bhutan where they stayed for nearly eight months. The report is significant because the Fathers were the first Westerners to visit and describe Bhutan. More important, the report gives a first-hand account of Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyel, the Founder of Bhutan. Introduction After exploring the Indian Ocean in the 15th century, the Portuguese settled as traders in several ports of the coast of India, and by mid 16th century Jesuit missionaries had been established in the Malabar Coast (the main centres being Cochin and Goa), in Bengal and in the Deccan. The first Jesuit Mission disembarked in India in 1542 with the arrival of Father Francis Xavier, proclaimed saint in 1622. * Luiza Maria Baillie holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree in English and French from Natal University, South Africa, and a Teacher's Certificate from the College of Education, Aberdeen, Scotland. She worked as a secretary and a translator, and is retired now. * Acknowledgements are due to the following who provided information, advice, encouragement and support. - Monsignor Cardoso, Ecclesiastic Counsellor at the Portuguese Embassy, the Vatican, Rome. - Dr. Paulo Teodoro de Matos of 'Comissao dos Descobrimentos Portugueses'; Lisbon, Portugal. - Dr. Michael Vinding, Counsellor, Resident Coordinator, Liaison Office of Denmark, Thimphu. 1 Father Estevao Cacella's Report on Bhutan in 1627 The aim of the Jesuits was to spread Christianity in India and in the Far East, but the regions of Tibet were also of great interest to them.