Harvey C. Condon Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tuya-Teslin Areal Northern British Columbia

BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES HON. E. C. CARSON, Minister JOHN F. WALKER, Dopulu Minis/#, BULLETIN No. 19 THE TUYA-TESLIN AREAL NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA by K. DeP. WATSON and W. H.MATHEWS 1944 CONTENTS. P*GS SUMMARY.................................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I.-Introduction ....................................................................................................... 6 Location............................................................................................................................. 6 Access................................................................................................................................. 7 Field-work .......................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................. 7 Previous Work.................................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER11.- I Topography ........................................................................................................................ 9 Kawdy Plateau.......................................................................................................... 9 Trenches ...................................................................................................................... 9 Teslin -

A Family Float Trip Down the Yukon River by John Morton

Refuge Notebook • Vol. 10, No. 39 • October 17, 2008 A family float trip down the Yukon River by John Morton the Yukon Quest. But it’s equally challenging when young kids are involved and you’re worried about making sure they’re having fun and are SAFE. This is a tall order when they’re inhaling mosquitoes, pad- dling through water as cold as ice with big hydraulics or camping in bear country. Our “wilderness” trip got a rocky start as we passed a sign below Whitehorse that cautioned about treated effluent being discharged into the river. Sev- eral miles below town we ran into a grocery cart stick- ing out of a muddy bar in a bend on the river. As we paddled across the 30-mile long Lake Lebarge, made famous by Robert Service’s poetic celebration of the Cremation of Sam McGee, we saw abundant signs of humans everywhere: tent sites, rusted cans, old cables, and broken glass. But gradually these modern archaeological arti- facts disappear as we get into dining on grayling and wild onions further down the river. Saxifrage, blue- Straight off the water to the telephone, Mika Morton, 11, bells, cinquefoil, wild sweet pea, and fleabane are flow- reconnects with civilization in Eagle after 700 miles on ering everywhere. Ravens stick their heads into the the Yukon River. Her sister Charly, 6, is not in such a holes of cliff and bank swallows to feed on nestlings rush. The Morton family made the 4-week wilderness and eggs. As we pass one of many spectacular cliffs trip from Whitehorse, Yukon Territory to Eagle, Alaska along the river, a pair of peregrine falcons double by canoe in June. -

Àghâ T'á Huch'gíxh Wusitîyi

Àghâ T’á Huch’gíxh wusitîyi gàw A time when salmon are no more Teslin, Yukon Gadzûsda, Virginia Smarch, at her fish camp on the Teslin River (VS 1980) “That is who we are, part of the land, part of the water.” Teslin Elder, the late Virginia Smarch - early days of Land Claims negotiations © Teslin Tlingit Council 2015 Teslin bridge (PM 2014) The That is who we are; Teslin part of the land, Story Teslin is located in southern-central Yukon on Teslin Lake, a major headwater of the Yukon River Drainage. These headwaters are in the heart of the traditional territory of the Teslin Tlingit people. The Teslin Tlingit have shared ancestry with the coastal Tlingit of Southeast Alaska and the part of the water Inland Tlingit of Taku River First Nation and Carcross-Tagish First Nation. There are five Teslin Tlingit Clans which play a central role in Teslin Tlingit Council’s (TTC) government structure and cultural practices. They are the Raven Child Clan (Kùkhhittàn), Frog Clan (Ishkìtàn), Wolf Clan (Yanyèdí), Beaver Clan (Dèshitàn), and Eagle Clan (Dakhl’awèdí). Chinook salmon (T’à), also known as King salmon, and a part of the Ishkìtàn Clan, is an important resource for Teslin Tlingit Citizens, being both culturally significant and important for subsistence. Once, Chinook salmon returned to the Teslin area in numbers that made the rivers run red. Over the last 30 years, pressures such as ocean bycatch, in-river commercial fisheries, and climate change have cumulatively taken a significant toll on the Chinook salmon returns. TTC has taken a proactive approach to salmon management and has implemented conservation measures for over 15 years in response to the alarming decrease in the salmon run size and quality. -

NATIONAL HISTORIC SITES SERVICE MANUSCRIPT REPORT NUMBER YUKON TERRITORY: a COMMUNITY of MEN by James Weppler

NATIONAL HISTORIC SITES SERVICE MANUSCRIPT REPORT NUMBER YUKON TERRITORY: A COMMUNITY OF MEN by James Weppler NATIONAL AND HISTORIC PARKS BRANCH DEPARTMENT OF INDIAN AFFAIRS AND NORTHERN DEVELOPMENT A COMMUNITY OF MEN Jim Weppler June 25, 1969. IAND Publication No. QS-2039-000-EE-A-ll A Community of Men The Klondike gold rush has eclipsed the early history of the Yukon Territory. This proves twofold unfortunate: first, because the Klondike rush cannot be understood without the historical frame work of the pre-1896 period; secondly, because the Klondike rush in its historical context can be considered a momentary aberration of Yukon history. The Yukon presents a case study of how to deal with an inaccessible territory and a harsh climate. The adventurers who dared the Yukon - fur traders and prospectors - formed an interdependent community. This society, based on the golden rule, gave the men the margin required for survival in the Yukon. The Klondike hordes temporarily destroyed the community of traders and prospectors, but a decade after the gold rush the spirit and practice of the Yukon pioneers partially reasserted itself. The immense wealth of the Klondike strike and the plethora of romantic, nostalgic writings on the 1897-98 rush have obscured the most successful response to the harsh environment of the Yukon. Contemporary companies, eager to mine Yukon resources at the urging of the Department of Northern Development, would do well to forget the El Dorado approach of the Klondike gold rush and, instead, to follow the example of the early traders and prospectors. In the beginning was the Indian. -

Teslin Tlingit Council Final Agreement

TESLIN TLINGIT COUNCIL FINAL AGREEMENT between THE TESLIN TLINGIT COUNCIL, THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA, and THE GOVERNMENT OF THE YUKON - 1 - AGREEMENT made this 29th day of May, 1993. AMONG: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada as represented by the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (hereinafter referred to as "Canada"); AND The Government of the Yukon as represented by the Government Leader of the Yukon on behalf of the Yukon (hereinafter referred to as "the Yukon"); AND The Teslin Tlingit Council as represented by the Teslin Tlingit Council General Council (hereinafter referred to as the "Teslin Tlingit Council") being the parties to the Teslin Tlingit Council Final Agreement (hereinafter referred to as "this Agreement"). WHEREAS: The Teslin Tlingit Council asserts aboriginal rights, titles and interests with respect to its Traditional Territory; the Teslin Tlingit Council wishes to retain, subject to this Agreement, the aboriginal rights, titles and interests it asserts with respect to its Settlement Land; the parties to this Agreement wish to recognize and protect a way of life that is based on an economic and spiritual relationship between Teslin Tlingit and the land; the parties to this Agreement wish to encourage and protect the cultural distinctiveness and social well-being of Teslin Tlingit; - 2 - the parties to this Agreement recognize the significant contributions of Teslin Tlingit and the Teslin Tlingit Council to the history and culture of the Yukon and Canada; the parties to this Agreement wish to enhance -

Yukon Mining &Geology Week

Yukon Mining &Geology Week MAY 31 – JUNE 4, 2021 activity Guide DISCOVERY SPONSOR: Partners & Sponsors presented in partnershiP: DISCOVERY SPONSOR: EXPLORER SPONSORS: PROSPECTOR SPONSORS: STAMPEDER SPONSORS: Yukon Mining &Geology Week MAY 31 – JUNE 4, 2021 2 Celebrating 125th Anniversary: Klondike Gold Rush Discovery Yukon Mining & Geology Week 2021 will take place from May 31 to June 4. This year is a special one as we commemorate and celebrate the 125th anniversary of the discovery of gold in the Klondike. Since that time, Yukon has built a mining history that has contributed to the territory’s diverse and inclusive culture, thriving economy, and a globally leading quality of life. Shaw Tláa (Kate Carmack) Gumboot mother Klondike Discoverer – Yukon Gold Rush 1896 INDUCTEE 2019 Share on Social: #KateDidIt Enter ONE or ALL completed activities on Facebook @YukonMining 100+ YEARS OF YUKON WOMEN IN MINING #YMGW2021 #Explore125Au to Kate Carmack’s induction, and the acknowledgement be entered into a draw for prizes of her role alongside the Klondike Discoverers in the from Yukon businesses Mining Hall of Fame, recognizes the untold and artists! contributions of all women in the mining industry. VIRTURAL YUKON MINING ACTIVITY BOOK Download this fun-for-all-ages activity book at: Yukonwim.ca/vym/vym-activities Yukon Mining &Geology Week MAY 31 – JUNE 4, 2021 3 OPEN TO ALL YUKONERS! Yukon Rocks & Walks Scavenger Hunt SPONSORED BY: DEADLINE TO POST: JUNE 11 Tag Us!” Tag @YukonMining & add #Explore125Au How it Works: #YMGW2021 1 Use the Scavenger Hunt Site Guide with the checklist and clues 2 Safely explore in your backyard, community and across the territory (Remember the Safe 6 + 1) 3 Photo op with your discovery and post: a. -

Yukon Territory King Salmon Studies

AYK REGION YUKON ESC. REPORT # 1 YUKON TERRITORY KING SALMON STUDIES 1970 ----- Robert C. Lebida Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Commercial Fisheries Anchorage. Alaska INTRODUCTION In conjunction with the Canadian Department of Fisheries salmon counting program at the Whitehorse Dam fishway (in operation since 1959), the Alaska Department of Fish and Game began a special king salmon sampling project during 1970. A smaller than average 1970 Yukon River king run warranted collection of additional information, Preliminary catch data indicated a large percentage of small males comprising the run. In view of this, the Whitehorse station was used to make further studies of fish numbers and the percentage of females in the escapement. Aerial surveys were also conducted to assess king salmon escapement magnitudes in major spawning systems and to survey index streams (identi- fied in 1968 (Figure 1). METHODS AND MATERIALS A fishery technician enumerated and sampled king salmon passing through the Whitehorse Dam fishway from July 26 to August 21. Daily records were kept of all kings utilizing the fishladder. Approximately -- ------- --· 17 percent of the run was sampled for age, sex and size information and then released unharmed. Scale samples were removed from the area of the first or second scale row above the lateral line on a diagonal down from the insertion of the dorsal fin to the origin of the anal fin. All scales were interpreted for age and data tabulated. For purposes of this report, a 42 salmon returning to spawn in 1970 would be the progeny of the 1966 run that migrated from fresh water to the ocean in the spring of 1968. -

Glaciation and the Physical, Chemical and Biological Limnology of Yukon ·Lakes

i i © Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1981 Cat. no. Fs 97-6/966 ISSN 0706-6457 Correct citation for this publication: Lindsey, C. C., K. Patalas, R. A. Bodaly, and C. P. Archibald. 1981. Glaciation and the physical, chemical and biological limnology of Yukon ·lakes. Can. Tech·. Rep. Fish. Aquat Sri. 966: v·i + 37 p. iii I TABLE OF CONTENTS .Iohle. Page g Temperature (temp) (°C) and oxygen (mg/L) profiles for lakes of the ABSTRACT/RESUME v Stewart, Takhini, Tatchun, Teslin, ·and White subdrainages of tile INTRODUCTION . 1 Yukon River drainage system 18 10 Water chemistry of lal~es of the Alsek, SOURCES AND METHODS 1 Liard, Peel, and Porcupine River drainage systems • . 19 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 11 Water chemistry of lakes of the Atlin, Physical Limnology Lewe~. Mandanna, Nordenskiold, Lake area 2 Pelly;·Big Salmon, and Little Maximum depth 2 Salmon subdrainages of the Yukon Elevation 2 River drainage system 20 Temperature . 2 12 Water chemistry of lakes of the Stewart, Chemical Limnology Takhini, Tatchun, Teslin, and White Total dissolved solids (TDS) 2 subdrainages of the Yukon River Major ions, chlorophyll a, and Secchi 2 drainage system 21 disc visibility • 13 Absolute abundance of crustaceans, Oxygen content . 2 rotifers. and total zooplankton Glaciological Background 2 (crustaceans plus rotifers) and Zooplankton Abundance and Distribution 3 relative abundance (% by number) Glacial History and Fish Distributions 4 of crustacean species for lakes Alsek and White River drainages 4 of the Alsek, Liard, Peel and Por- Yukon River drainages 4 cupine River drainage systems 22 Liard River drainages . 6 14 Absolute abundance of crustaceans, Peel and Porcupine River drainages 6 rotifers, and total zooplankton (crustaceans plus rotifers) and ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7 relative abundance (% by number) of crustacean species for lakes REFERENCES 8 of the Atlin, Lewes, Mandanna, Nordenskiold, Pelly, Big Salmon, and Little Salmon subdrainages of the Yukon River drainage LIST OF TABLES system . -

Teslin Strategic Forest Management Plan

Teslin Strategic Forest Management Plan Strategic Direction for Sustainable Forest Resource Development Strategic Forest Management Plan for the Teslin Tlingit Traditional Territory TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION . 1 1.1 Purpose. 1 1.2 The Need and the Challenge . 1 1.3 Planning Region and Time Frame . 2 1.4 Planning Region Description . 2 1.4.1 Land . 2 1.4.2 Environment . 3 1.4.3 Climate, Soil and Vegetation . 3 1.4.4 Forests. 3 1.4.5 Forest Disturbances . 5 1.4.6 Fish and Wildlife . 6 1.4.7 The People . 8 1.4.8 The Economy . 9 1.4.9 Special Places . 10 2.0 PRINCIPLES FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT . 12 Vision Statements . 12 3.0 FOREST PLANNING PROCESS . 13 3.1 Legislative Context . 13 3.2 Planning Framework . 13 3.3 Planning Process . 17 3.3.1 Chronology of Key Steps . 17 3.3.2 Participation in Strategic Forest Management Planning . 17 4.0 STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS FROM PLANNING AND LEGISLATIVE INITIATIVES . 18 4.1 Teslin Tlingit Council Final Agreement . 18 4.2 Land Use Planning in the Teslin Tlingit Traditional Territory . 19 4.3 Nisutlin River Delta National Wildlife Area . 19 4.4 Priorities of the Teslin Tlingit Council . 20 4.5 Priorities of the Yukon Government in regards to Forest Management . 20 4.6 Teslin Tlingit Council Settlement Land and Resources Act . 21 4.7 Teslin Tlingit Council Fish and Wildlife Act . 21 4.8 Teslin Regional Tourism Plan . 21 4.9 Teslin Integrated Fish and Wildlife Management Plan . 22 4.10 Yukon Salmon Committee . -

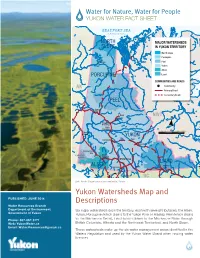

Yukon Watersheds Map and Descriptions

Water for Nature, Water for People YUKON WATER FACT SHEET Left: North Slope tundra and wetlands, Yukon Yukon Watersheds Map and PUBLISHED: JUNE 2014 Descriptions Water Resources Branch Department of Environment Six major watersheds drain the territory, each with several tributaries: the Alsek, Government of Yukon Yukon, Porcupine (which drains to the Yukon River in Alaska), Peel (which drains to the Mackenzie Delta), Liard (which drains to the Mackenzie Basin through Phone: 867-667-3171 Web: YukonWater.ca British Columbia, Alberta and the Northwest Territories), and North Slope. Email: [email protected] These watersheds make up the six water management areas identified in the Waters Regulation and used by the Yukon Water Board when issuing water licences. 1 Water for Nature, Water for People YUKON WATER FACT SHEET City of Whitehorse, and Yukon River Yukon River Basin (including the Alsek River Basin Porcupine River Basin) The Alsek River drains the southwestern portion of the Yukon to the Pacific Ocean. It is classified as a The Yukon River Headwaters contains the Southern Canadian Heritage River because of its significant Lakes region of Yukon and Northern British Columbia; natural resources: massive ice fields, high mountain there are glaciers throughout the mountains of these peaks, unique geologic history, coastal and interior headwaters. The Teslin River joins the Yukon River plant communities, significant grizzly bear population, north of Lake Laberge, contributing water mainly from and diverse bird species. snowmelt runoff in the upper portions of the basin. The Pelly and Stewart Rivers drain the eastern portion of the drainage, including mountainous terrain. -

Teslin Watershed

EiNiiOIllI.....c.... Catalogue of Fish and S ream esources of he es i a ershed British Columbia and CATALOGUE OF FISH AND STREAM RESOURCES OF THE TESLIN WATERSHED Alaska Northwest Terr. Staff of Northern British Columbia and Yukon Division DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT FISHERIES AND MARINE SERVICE PACIFIC REGION VANCOUVER 1973 , Teslin Lake • Highway bridge crossing Teslin R. at Johnsons Crossing, Mile 836.3·of the Alaska Highway. "• FOR E WaR D This catalogue is a historical record and information source concerning fish species and their habitats in the Teslin River drainage basin. It has been assembled for the use of those people involved in fisheries management and environmental protection and is the first of a series covering the major drain age basins in the Northern B.C. and Yukon Division. The rapidity with which unnatural change now takes place in the north makes it essential that managers be able to control such developments or changes so that environmental damage is avoided or at least minimized. Harvest of the fishery resources must be controlled by sensible management based on biologically sound facts; this catalogue provides a tool towards these ends. A. Gibson, Chief, Northern B.C. and Yukon Division. ABSTRACT Fourteen species are represented in the fish stocks of the Teslin watershed. The Teslin watershed is a 12,000 square-mile area in the south-central Yukon Territory and northern British Columbia. Physical, chemical and biological characteristics are presented for each of 8 major tributary systems. Detail on life history and abundance is known to a limited degree for chinook salmon only. -

Yukon River: Thirty Mile Section 20-Year Monitoring Report

Yukon River: Thirty Mile Section 20-year Monitoring Report Prepared for: Yukon Parks Department of Environment Government of Yukon and the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board Prepared by: Bruce K. Downie PRP Parks: Research & Planning Inc. Whitehorse, Yukon Purpose of the Report The Thirty Mile Section of the Yukon River was designated as a Canadian Heritage River in 1991 – the second designation in Yukon. The CHRS requires regular monitoring of the natural, heritage and recreational values underpinning each designation. This report presents the results of the 20- year review of the river values and key elements of the intended and articulated management strategies for the area. This analysis points out the characteristics and qualities of the designated river that have been consistently and naturally maintained as well as those activities and management actions being implemented to ensure continued integrity of the river values. This report is not intended to be a thorough review of the management plan but will make a contribution to formal management plan reviews when they are undertaken. Acknowledgements Thanks are due to those individuals consulted through this analysis and especially to the dedicated individuals in Yukon and First Nations governments who continue to work towards the protection of the natural and cultural values of the Thirty Mile segment of the Yukon River. Thanks are also extended to the Parks Canada Agency for funding this project in part and providing support through the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board Secretariat.