Metallicity, Debris Discs and Planets � � � J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measuring the Velocity Field from Type Ia Supernovae in an LSST-Like Sky

Prepared for submission to JCAP Measuring the velocity field from type Ia supernovae in an LSST-like sky survey Io Odderskov,a Steen Hannestada aDepartment of Physics and Astronomy University of Aarhus, Ny Munkegade, Aarhus C, Denmark E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. In a few years, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope will vastly increase the number of type Ia supernovae observed in the local universe. This will allow for a precise mapping of the velocity field and, since the source of peculiar velocities is variations in the density field, cosmological parameters related to the matter distribution can subsequently be extracted from the velocity power spectrum. One way to quantify this is through the angular power spectrum of radial peculiar velocities on spheres at different redshifts. We investigate how well this observable can be measured, despite the problems caused by areas with no information. To obtain a realistic distribution of supernovae, we create mock supernova catalogs by using a semi-analytical code for galaxy formation on the merger trees extracted from N-body simulations. We measure the cosmic variance in the velocity power spectrum by repeating the procedure many times for differently located observers, and vary several aspects of the analysis, such as the observer environment, to see how this affects the measurements. Our results confirm the findings from earlier studies regarding the precision with which the angular velocity power spectrum can be determined in the near future. This level of precision has been found to imply, that the angular velocity power spectrum from type Ia supernovae is competitive in its potential to measure parameters such as σ8. -

Chapter 1 a Theoretical and Observational Overview of Brown

Chapter 1 A theoretical and observational overview of brown dwarfs Stars are large spheres of gas composed of 73 % of hydrogen in mass, 25 % of helium, and about 2 % of metals, elements with atomic number larger than two like oxygen, nitrogen, carbon or iron. The core temperature and pressure are high enough to convert hydrogen into helium by the proton-proton cycle of nuclear reaction yielding sufficient energy to prevent the star from gravitational collapse. The increased number of helium atoms yields a decrease of the central pressure and temperature. The inner region is thus compressed under the gravitational pressure which dominates the nuclear pressure. This increase in density generates higher temperatures, making nuclear reactions more efficient. The consequence of this feedback cycle is that a star such as the Sun spend most of its lifetime on the main-sequence. The most important parameter of a star is its mass because it determines its luminosity, ef- fective temperature, radius, and lifetime. The distribution of stars with mass, known as the Initial Mass Function (hereafter IMF), is therefore of prime importance to understand star formation pro- cesses, including the conversion of interstellar matter into stars and back again. A major issue regarding the IMF concerns its universality, i.e. whether the IMF is constant in time, place, and metallicity. When a solar-metallicity star reaches a mass below 0.072 M ¡ (Baraffe et al. 1998), the core temperature and pressure are too low to burn hydrogen stably. Objects below this mass were originally termed “black dwarfs” because the low-luminosity would hamper their detection (Ku- mar 1963). -

Search for Brown-Dwarf Companions of Stars⋆⋆⋆

A&A 525, A95 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201015427 & c ESO 2010 Astrophysics Search for brown-dwarf companions of stars, J. Sahlmann1,2, D. Ségransan1,D.Queloz1,S.Udry1,N.C.Santos3,4, M. Marmier1,M.Mayor1, D. Naef1,F.Pepe1, and S. Zucker5 1 Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, 51 Chemin des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] 2 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching bei München, Germany 3 Centro de Astrofísica, Universidade do Porto, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal 4 Departamento de Física e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Portugal 5 Department of Geophysics and Planetary Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel Received 19 July 2010 / Accepted 23 September 2010 ABSTRACT Context. The frequency of brown-dwarf companions in close orbit around Sun-like stars is low compared to the frequency of plane- tary and stellar companions. There is presently no comprehensive explanation of this lack of brown-dwarf companions. Aims. By combining the orbital solutions obtained from stellar radial-velocity curves and Hipparcos astrometric measurements, we attempt to determine the orbit inclinations and therefore the masses of the orbiting companions. By determining the masses of poten- tial brown-dwarf companions, we improve our knowledge of the companion mass-function. Methods. The radial-velocity solutions revealing potential brown-dwarf companions are obtained for stars from the CORALIE and HARPS planet-search surveys or from the literature. The best Keplerian fit to our radial-velocity measurements is found using the Levenberg-Marquardt method. -

Public Naming of Exoplanets and Their Stars: Implementation and Outcomes of the IAU100

Public Naming of Exoplanets and Their Stars: Implementation and Outcomes of the IAU100 Best Practice Best NameExoWorlds Global Project Eric Mamajek Debra Meloy Elmegreen Alain Lecavelier des Etangs Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Vassar College Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris Institute of Technology [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Eduardo Monfardini Penteado Lars Lindberg Christensen [email protected] NSF’s NOIRLab [email protected] Gareth Williams [email protected] Hitoshi Yamaoka National Astronomical Observatory of Guillem Anglada-Escudé Japan (NAOJ) Institute for Space Science (ICE/CSIC), [email protected] Queen Mary University of London Keywords [email protected] exoplanets, IAU nomenclature The IAU100 NameExoWorlds public naming campaign was a core project during the International Astronomical Union’s 100th anniversary (IAU100) in 2019, giving the opportunity to everyone, everywhere, to propose official names for exoplanets and their host stars. With IAU100 NameExoWorlds the IAU encouraged all peoples of Earth to consider themselves as “Citizens of the Universe”, united “under one sky”. The 113 national campaigns involved hundreds of thousands of people in a global effort to bring the public closer to science by allowing them to participate in the process of naming stars and planets, and learning more about astronomy in the process. The campaign resulted in nearly 425 000 votes, and 113 new IAU-recognised proper names for exoplanets and 113 new names for their stars. The IAU now officially recognises the chosen proper names in addition to their previous scientific designations, and they appear in popular databases. Introduction wished to contribute to the fraternity of all through international cooperation, the IAU people with a significant token of global is the authority responsible for assigning Over the past three decades, astronomers identity. -

The UV Perspective of Low-Mass Star Formation

galaxies Review The UV Perspective of Low-Mass Star Formation P. Christian Schneider 1,* , H. Moritz Günther 2 and Kevin France 3 1 Hamburger Sternwarte, University of Hamburg, 21029 Hamburg, Germany 2 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research; Cambridge, MA 02109, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, University of Colorado, Denver, CO 80203, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 January 2020; Accepted: 29 February 2020; Published: 21 March 2020 Abstract: The formation of low-mass (M? . 2 M ) stars in molecular clouds involves accretion disks and jets, which are of broad astrophysical interest. Accreting stars represent the closest examples of these phenomena. Star and planet formation are also intimately connected, setting the starting point for planetary systems like our own. The ultraviolet (UV) spectral range is particularly suited for studying star formation, because virtually all relevant processes radiate at temperatures associated with UV emission processes or have strong observational signatures in the UV range. In this review, we describe how UV observations provide unique diagnostics for the accretion process, the physical properties of the protoplanetary disk, and jets and outflows. Keywords: star formation; ultraviolet; low-mass stars 1. Introduction Stars form in molecular clouds. When these clouds fragment, localized cloud regions collapse into groups of protostars. Stars with final masses between 0.08 M and 2 M , broadly the progenitors of Sun-like stars, start as cores deeply embedded in a dusty envelope, where they can be seen only in the sub-mm and far-IR spectral windows (so-called class 0 sources). -

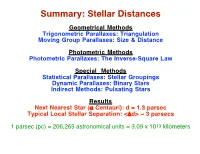

Summary: Stellar Distances

Summary: Stellar Distances Geometrical Methods Trigonometric Parallaxes: Triangulation Moving Group Parallaxes: Size & Distance Photometric Methods Photometric Parallaxes: The Inverse-Square Law Special Methods Statistical Parallaxes: Stellar Groupings Dynamic Parallaxes: Binary Stars Indirect Methods: Pulsating Stars Results Next Nearest Star (α Centauri): d = 1.3 parsec Typical Local Stellar Separation: <Δd> ~ 3 parsecs 1 parsec (pc) = 206,265 astronomical units = 3.09 x 1013 kilometers Stellar Motions The space velocity, v, can always be separated into a radial component, vr, and a tangential component, vt v2 = vr2 + vt2 The radial part is what causes the distance to change. The tangential part is what causes the direction to change. Stellar Motions The radial and tangential components are perpendicular to one another, so the space velocity is given by: v2 = vr2 + vt2 (Remember Pythagoras?) The radial and tangential parts of a star’s velocity are determined separately - and in quite different ways. Determining the Radial Velocity Radial velocities are obtained by observing the star’s spectrum and making use of the Doppler Effect: vr/c = (λ - λo)/λo (λo is the emitted wavelength, λ the observed wavelength) Generally many absorption lines of known wavelength in a star’s spectrum are measured to obtain an accurate value for the star’s radial velocity. Determining the Tangential Velocity The proper motion of a star, µ , is the annual rate at which its location (direction) on the celestial sphere changes. (This is in addition to the annual parallactic motion.) It is usually expressed in seconds-of-arc per year. Tangential velocities are obtained by measuring both a star’s proper motion, µ , and its distance, d: +vt(km/s) = 4.74µ (“/yr) d(pc) (The “constant” 4.74 is appropriate for the units used.) (Note: 1 km/s = 2,235 mph = 1,944 knots) The distance, d, is usually obtained from a measurement of the trigonometric parallax, p. -

A Brief on the Exo-Planet and Star Assigned to Nigeria to Name by Iau

A BRIEF ON THE EXO-PLANET AND STAR ASSIGNED TO NIGERIA TO NAME BY IAU. Within the framework of its 100th anniversary commemorations, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) is organizing the IAU100 NameExoWorlds gloBal competition that allows any country in the world including Nigeria to give a popular name to a selected exoplanet and its host star. Star: HD 43197 Exo-Planet: HD 43197b STAR- HD 43197 HD 43197's star type is suBgiant star that can Be located in the constellation of canis major. The description is Based on the spectral class. HD 43197 is not part of the constellation outline But is within the Borders of the constellation. Based on the spectral type (G8/K0IV/V) of the star, the star's color is white to yellow. The star cannot Be seen By the naked eye, you need a telescope to see it. HD 43197 has at least 1 extrasolar planets Believed to Be in orBit around the star. Using the most recent figures given By the 2007 Hipparcos data, the star is 183.65 light years away from us. For HD 43197, the location is 06h 13m 35.56s and -29° 53` 50.3 and is determined By the Right Ascension (R.A.) and Declination (Dec.) which are equivalent to the Longitude and Latitude of the Earth. DISTANCE TO HD 43197 Using the original Hipparcos data that was released in 1997, the parallax to the star was given as 18.20 which gave the calculated distance to HD 43197 as 179.21 light years away from Earth or 54.95 parsecs. -

Proper Motion of a Star

Page 1 of 7 Group Members: __________________ __________________ __________________ Proper Motion of a Star In this exercise you will measure the proper motion of Barnard’s Star and use it, with a given parallax and radial velocity, to determine the space motion of the star. Background information In 1718 Edmund Halley had noted that some stars were not fixed, but appeared to move in the sky relative to other stars. Arctures in Boötes and Sirius in Canis Major were the first stars detected by Halley to have proper motion. Proper motion is the angular change in position of a star across our line of sight, measured in arc seconds per year, and symbolized with the Greek letter “mu” μ. Proper motion is generally measured by taking photographs several years apart and measuring the movement of the image of a star with respect to more distant background stars over that time period. Usually decades must elapse between successive photographs before a reliable measurement can be made. The star with the largest proper motion was discovered by E. E. Barnard in 1916 at Yerkes Observatory. This star, now called Barnard’s Star, is a 9.5 magnitude star located in the constellation Ophiuchus. Its proper motion is so much larger than that of any other star that it is considered to be virtually a “runaway” star. Even so, the angular velocity is small enough that measurements must be made from photographs taken many years apart. The negatives of Barnard’s Star provided in this lab were taken in 1924 and 1951 respectively. -

William Pendry Bidelman (1918-2011)

William Pendry Bidelman (1918–2011)1 Howard E. Bond2 Received ; accepted arXiv:1609.09109v1 [astro-ph.SR] 28 Sep 2016 1Material for this article was contributed by several family members, colleagues, and former students, including: Billie Bidelman Little, Joseph Little, James Caplinger, D. Jack MacConnell, Wayne Osborn, George W. Preston, Nancy G. Roman, and Nolan Walborn. Any opinions stated are those of the author. 2Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; [email protected] –2– ABSTRACT William P. Bidelman—Editor of these Publications from 1956 to 1961—passed away on 2011 May 3, at the age of 92. He was one of the last of the masters of visual stellar spectral classification and the identification of peculiar stars. I re- view his contributions to these subjects, including the discoveries of barium stars, hydrogen-deficient stars, high-galactic-latitude supergiants, stars with anomalous carbon content, and exotic chemical abundances in peculiar A and B stars. Bidel- man was legendary for his encyclopedic knowledge of the stellar literature. He had a profound and inspirational influence on many colleagues and students. Some of the bizarre stellar phenomena he discovered remain unexplained to the present day. Subject headings: obituaries (W. P. Bidelman) –3– William Pendry Bidelman—famous among his astronomical colleagues and students for his encyclopedic knowledge of stellar spectra and their peculiarities—passed away at the age of 92 on 2011 May 3, in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. He was Editor of these Publications from 1956 to 1961. Bidelman was born in Los Angeles on 1918 September 25, but when the family fell onto hard financial times, his mother moved with him to Grand Forks, North Dakota in 1922. -

Radial Velocity Survey for Planets and Brown Dwarf Companions to Very Young Brown Dwarfs and Very Low-Mass Stars in Chamaeleon I with UVES at the VLT�,

A&A 446, 1165–1176 (2006) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20053406 & c ESO 2006 Astrophysics Radial velocity survey for planets and brown dwarf companions to very young brown dwarfs and very low-mass stars in Chamaeleon I with UVES at the VLT, V. Joergens Leiden Observatory / Sterrewacht Leiden, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] Received 11 May 2005 / Accepted 6 September 2005 ABSTRACT We present results of a radial velocity (RV) survey for planets and brown dwarf (BD) companions to very young BDs and (very) low-mass stars in the Cha I star-forming cloud. Time-resolved high-resolution echelle spectra of Cha Hα 1–8 and Cha Hα 12 (M6–M8), B34 (M5), CHXR 74 (M4.5), and Sz 23 (M2.5) were taken with UVES at the VLT between 2000 and 2004. The precision achieved for the relative RVs range between 40 and 670 m s−1 and is sufficient to detect Jupiter mass planets around the targets. This is the first RV survey of very young BDs. It probes multiplicity, which is a key parameter for formation in an as yet unexplored domain, in terms of age, mass, and orbital < separation. We find that the subsample of ten BDs and very low-mass stars (VLMSs, M ∼ 0.12 M, spectral types M5−M8) has constant RVs on time scales of 40 days and less. For this group, estimates of upper limits for masses of hypothetical companions range between 0.1 MJup and 1.5 MJup for assumed orbital separations of 0.1 AU. -

Lecture21.Pdf

Extraterrestrial Life: Lecture #21 Transits As seen from Earth, both Mercury and Venus occasionally Homework #5 is due Thursday (limited office hours this transit the face of the Sun: afternoon, but I will be available all tomorrow afternoon if you have queries) Transits of Venus are rare: occur in pairs Last time discussed radial velocity method for finding every ~200 years (next planets - very good for finding massive planets one in 2012) How can we find habitable planets (Earth mass, in roughly Earth-like orbits)? Extraterrestrial Life: Spring 2008 Extraterrestrial Life: Spring 2008 Transits Magnitude of the transit signal If an extrasolar planet transits its Fraction of the starlight blocked is just host star as seen from Earth, cannot the fraction of the stellar disk that is resolve the disk of the star and directly covered - i.e. the ratio of the area of see the transit the planet disk to the stellar disk. Planet has radius R , star has radius R Instead, measure the reduction in the starlight caused by p * the transiting planet blocking light from a fraction of the Fractional drop is: 2 2 star’s surface (i.e. see a very partial eclipse of the star). "Rp # Rp & f = 2 = % ( "R* $ R* ' Extraterrestrial Life: Spring 2008 Extraterrestrial Life: Spring 2008 ! Relation of the light Sun’s radius is 6.96 x 108 m curve to the geometry Jupiter’s radius is 7.14 x 107 m of the transit Earth’s radius is 6.4 x 106 m 2 7 2 " Rp % " 7.14 (10 m% f = $ ' = $ 8 ' = 0.01 # R* & # 6.96 (10 m& The signal for a Jupiter radius planets is ~1% drop in the stellar light during the transit - this is large enough to see from the ground. -

WIDC-A-Ras Directory of Astronomical Data Files

Tin Mo. '« i WIDC-A-RaS 78-05 National Space Science Data Center/ World Data Center A For Rockets and Satellites Directory of Astronomical Data Files September 1978 PREFACE This Directory of Astronomical Data Files has been prepared by the Data Task Force of the Interagency Coordination Committee for Astronomy (ICCA) in cooperation with the National Space Science Data Center (NSSDC). The purpose of the Directory is to provide a listing.which will enable a user to locate stellar and extragalactic data sources keyed along with sufficient descriptive information to permit him to assess the value of the files for his use as well as the status and availability of the com- pilations. An ad hoc committee of the Federal Council for Science and Technol- ogy, ICCA, was composed of representatives from each of the major Federal agencies funding astronomical research. Its charge to the Data Task Force was "to outline a sequence of steps that the Federal agencies might take to coordinate the archiving of astronomical data in order to maximize utility." Among the recommendations contained in its final report, the Task Force advocated that the Federal, agencies "prepare a directory of astronomical data centers and other sources for both machine-readable and non-machine-readable data, including type of data, description of file, method of access, person-in-charge, and location for distribution to agen- cies and the astronomical researchers they support." The ICCA subsequent- ly reappointed the Task Force with a revised charge to suggest appropriate steps to carry out its recommendations, including cost estimates and ac- ceptability to the astronomical community.