1 Revision 3: Phase Transformation of Hydrous Ringwoodite to the Lower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantification of Water in Hydrous Ringwoodite

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 28 January 2015 EARTH SCIENCE doi: 10.3389/feart.2014.00038 Quantification of water in hydrous ringwoodite Sylvia-Monique Thomas 1*,StevenD.Jacobsen2, Craig R. Bina 2, Patrick Reichart 3, Marcus Moser 3, Erik H. Hauri 4, Monika Koch-Müller 5,JosephR.Smyth6 and Günther Dollinger 3 1 Department of Geoscience, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV, USA 2 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA 3 Department für Luft- und Raumfahrttechnik LRT2, Universität der Bundeswehr München, Neubiberg, Germany 4 Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, DC, USA 5 Helmholtz-Zentrum Potsdam, Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum (GFZ), Potsdam, Germany 6 Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA Edited by: Ringwoodite, γ-(Mg,Fe)2SiO4, in the lower 150 km of Earth’s mantle transition zone Mainak Mookherjee, Cornell (410–660 km depth) can incorporate up to 1.5–2wt% H2O as hydroxyl defects. We University, USA present a mineral-specific IR calibration for the absolute water content in hydrous Reviewed by: ringwoodite by combining results from Raman spectroscopy, secondary ion mass Geoffrey David Bromiley, University of Edinburgh, UK spectrometry (SIMS) and proton-proton (pp)-scattering on a suite of synthetic Mg- and Marc Blanchard, CNRS - Université Fe-bearing hydrous ringwoodites. H2O concentrations in the crystals studied here Pierre et Marie Curie, France range from 0.46 to 1.7wt% H2O (absolute methods), with the maximum H2Oin *Correspondence: the same sample giving 2.5 wt% by SIMS calibration. Anchoring our spectroscopic Sylvia-Monique Thomas, results to absolute H-atom concentrations from pp-scattering measurements, we report Department of Geoscience, University of Nevada Las Vegas, frequency-dependent integrated IR-absorption coefficients for water in ringwoodite −1 −2 4505 S. -

Seismic Evidence for Water Deep in Earth's Upper Mantle

R EPORTS million years ago (Ma), subduction mainly took place in the eastern Mediterranean with Seismic Evidence for Water Deep mostly south- and eastward-dipping subduc- tion. Remnants of the subducted slab can be in Earth’s Upper Mantle found in the lower mantle between 1300 and 1900 km depth under locations such as Egypt Mark van der Meijde,* Federica Marone, Domenico Giardini, and Libya (18). Subduction was ubiquitous Suzan van der Lee after 80 Ma. At present, active subduction zones are found in southern Italy and Greece. Water in the deep upper mantle can influence the properties of seismic dis- We investigated seismic discontinuities in the continuities in the mantle transition zone. Observations of converted seismic deep upper mantle of the Mediterranean re- waves provide evidence of a 20- to 35-kilometer-thick discontinuity near a gion by searching seismograms for seismic S depth of 410 kilometers, most likely explained by as much as 700 parts per waves that converted from P waves at the million of water by weight. discontinuities. Our search was facilitated by a recent temporary deployment of mobile Two major seismic velocity discontinuities, lies in the mantle transition zone would broadband seismic stations [MIDSEA (19)] at nominal depths of 410 and 660 km, border have no seismically observable effect on along the plate boundary between Eurasia the transition zone of Earth’s mantle. The the thickness of the 660-km discontinuity and Africa. We analyzed over 500 seismo- 410-km discontinuity is the result of the tran- (7), whereas the effect on the 520-km dis- grams recorded in the Mediterranean region sition from olivine to wadsleyite. -

Influence of the Ringwoodite-Perovskite Transition on Mantle Convection in Spherical Geometry As a Function of Clapeyron Slope A

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Solid Earth Discuss., 3, 713–741, 2011 Solid Earth www.solid-earth-discuss.net/3/713/2011/ Discussions doi:10.5194/sed-3-713-2011 © Author(s) 2011. CC Attribution 3.0 License. This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Solid Earth (SE). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in SE if available. Influence of the Ringwoodite-Perovskite transition on mantle convection in spherical geometry as a function of Clapeyron slope and Rayleigh number M. Wolstencroft1,* and J. H. Davies1 1School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Main Building, Park Place, Cardiff, Wales, CF10 3AT, UK *now at: University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Received: 21 July 2011 – Accepted: 27 July 2011 – Published: 4 August 2011 Correspondence to: J. H. Davies ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. 713 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract We investigate the influence on mantle convection of the negative Clapeyron slope ringwoodite to perovskite and ferro-periclase mantle phase transition, which is corre- lated with the seismic discontinuity at 660 km depth. In particular, we focus on un- 5 derstanding the influence of the magnitude of the Clapeyron slope (as measured by the Phase Buoyancy parameter, P ) and the vigour of convection (as measured by the Rayleigh number, Ra) on mantle convection. We have undertaken 76 simulations of isoviscous mantle convection in spherical geometry varying Ra and P . Three domains of behaviour were found: layered convection for high Ra and more negative P , whole 10 mantle convection for low Ra and less negative P and transitional behaviour in an inter- vening domain. -

The Eyes Have It

news and views flow of heat and matter in the interior2. This Irifune and Isshiki1 have shown such transition to higher pressures (as can be seen flow, in turn, drives the tectonic evolution artificial separation to be misleading by in Irifune and Isshiki’s Fig. 3 on page 704), so of the surface, including the occurrence of experimentally demonstrating Mg–Fe ex- the onset of the transition in pyrolite is post- volcanism and seismicity. change between a, b, garnet and clino- poned to greater depths relative to that in Olivine, a solid solution of forsterite pyroxene. We have known5 for some time Fo89. On the other side of the phase change, b (Mg2SiO4) and fayalite (Fe2SiO4), has the that the proportions of these minerals vary does not partition Fe into garnet as strong- a b approximate composition (Mg0.89 Fe0.11)2SiO4 with depth, as shown by the bold white lines ly as does , so is not initially Mg-enriched, (called forsterite-89 or Fo89) in samples from in Fig. 1, but Irifune and Isshiki have now and the completion of the a–b transition the shallow mantle. It transforms from the measured the accompanying variations in is not postponed relative to Fo89. The net olivine (a) phase to wadsleyite (b), changing the compositions of coexisting minerals, effect of postponing onset but not co8m- again to ringwoodite (g) at greater depths shown by the colours. In isolated Fo89 pletion is to concentrate the transition into and eventually breaking down to a mixture of olivine, mineral compositions must remain a narrower range of depths, decreasing the silicate perovskite and magnesiowüstite. -

The Upper Mantle and Transition Zone

The Upper Mantle and Transition Zone Daniel J. Frost* DOI: 10.2113/GSELEMENTS.4.3.171 he upper mantle is the source of almost all magmas. It contains major body wave velocity structure, such as PREM (preliminary reference transitions in rheological and thermal behaviour that control the character Earth model) (e.g. Dziewonski and Tof plate tectonics and the style of mantle dynamics. Essential parameters Anderson 1981). in any model to describe these phenomena are the mantle’s compositional The transition zone, between 410 and thermal structure. Most samples of the mantle come from the lithosphere. and 660 km, is an excellent region Although the composition of the underlying asthenospheric mantle can be to perform such a comparison estimated, this is made difficult by the fact that this part of the mantle partially because it is free of the complex thermal and chemical structure melts and differentiates before samples ever reach the surface. The composition imparted on the shallow mantle by and conditions in the mantle at depths significantly below the lithosphere must the lithosphere and melting be interpreted from geophysical observations combined with experimental processes. It contains a number of seismic discontinuities—sharp jumps data on mineral and rock properties. Fortunately, the transition zone, which in seismic velocity, that are gener- extends from approximately 410 to 660 km, has a number of characteristic ally accepted to arise from mineral globally observed seismic properties that should ultimately place essential phase transformations (Agee 1998). These discontinuities have certain constraints on the compositional and thermal state of the mantle. features that correlate directly with characteristics of the mineral trans- KEYWORDS: seismic discontinuity, phase transformation, pyrolite, wadsleyite, ringwoodite formations, such as the proportions of the transforming minerals and the temperature at the discontinu- INTRODUCTION ity. -

RINGWOODITE-OLIVINE ASSEMBLAGES in DHOFAR 922 L6 MELT VEINS. D. D. Badjukov1, F. Brandstaetter2, G. Kurat3, E. Libowitzky3 and J

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVI (2005) 1684.pdf RINGWOODITE-OLIVINE ASSEMBLAGES IN DHOFAR 922 L6 MELT VEINS. D. D. Badjukov1, F. Brandstaetter2, G. Kurat3, E. Libowitzky3 and J. Raitala4, 1V.I. Vernadsky Institute RAS, Kosygin str. 19, 11991, Moscow, Russia, [email protected], 2Naturhistorisches Museum, Burgring 7, A-1010 Wien, Austria, [email protected], 3Universität Wien, Institut für Geologische Wissenschaften, Althanstr. 14, A- 1090 Wien, Austria, [email protected], 3University of Oulu, FIN 90401, Finland, [email protected], Introduction. Shock-induced melt veins stand out gave in average a composition enriched in Al and Ca among different types of veins in ordinary chondrites relatively to the host chondrite, which is proposed to due to their specific mineral assemblages. They often be due to preferred melting of plagioclase. Embedded contain high pressure polymorphs of host chondrite in the veins are non-melted inclusions of the host minerals like wadsleyite, ringwoodite, majorite, chondrite which were converted to different phases, akimotoite and so on [1-4]. Because of a compositional common are ringwoodite, olivine, majorite, pyroxene similarity between chondrites and the Earth’s mantle, and plagioclase glass. Several areas contain also green the shock melt veins are an unique natural source of wadsleyite aggregates. Some majorite and ringwoodite study of mantle mineralogy. Two lithologies are clasts are enveloped by a silica mantle. Ringwoodite is characteristic for the veins: silicates, oxide(s), observed also at a distance of no more than ~0.5 mm sulfide(s) and metal crystallized from a melt and solid from vein walls in the host rock. -

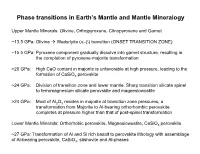

Phase Transitions in Earth's Mantle and Mantle Mineralogy

Phase transitions in Earth’s Mantle and Mantle Mineralogy Upper Mantle Minerals: Olivine, Orthopyroxene, Clinopyroxene and Garnet ~13.5 GPa: Olivine Æ Wadsrlyite (DE) transition (ONSET TRANSITION ZONE) ~15.5 GPa: Pyroxene component gradually dissolve into garnet structure, resulting in the completion of pyroxene-majorite transformation >20 GPa: High CaO content in majorite is unfavorable at high pressure, leading to the formation of CaSiO3 perovskite ~24 GPa: Division of transition zone and lower mantle. Sharp transition silicate spinel to ferromagnesium silicate perovskite and magnesiowustite >24 GPa: Most of Al2O3 resides in majorite at transition zone pressures, a transformation from Majorite to Al-bearing orthorhombic perovskite completes at pressure higher than that of post-spinel transformation Lower Mantle Minerals: Orthorhobic perovskite, Magnesiowustite, CaSiO3 perovskite ~27 GPa: Transformation of Al and Si rich basalt to perovskite lithology with assemblage of Al-bearing perovskite, CaSiO3, stishovite and Al-phases Upper Mantle: olivine, garnet and pyroxene Transition zone: olivine (a-phase) transforms to wadsleyite (b-phase) then to spinel structure (g-phase) and finally to perovskite + magnesio-wüstite. Transformations occur at P and T conditions similar to 410, 520 and 660 km seismic discontinuities Xenoliths: (mantle fragments brought to surface in lavas) 60% Olivine + 40 % Pyroxene + some garnet Images removed due to copyright considerations. Garnet: A3B2(SiO4)3 Majorite FeSiO4, (Mg,Fe)2 SiO4 Germanates (Co-, Ni- and Fe- -

Time-Varying Subduction and Rollback Velocities in Slab Stagnation

Phase transformation of harzburgite and stagnant slab in the mantle transition zone Y. Zh ang 1,2, Y. Wu1, Y. Wang2, Z. Jin1, C. R. Bina3 1State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources (GPMR), China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China 2Center for Advanced Radiation Sources, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA 3Dept. of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA Subducted materials play an important role in affecting chemical composition and structure of the mantle transition zone. Harzburgite is generally accepted as an important part of subducting slabs, overlain by a layer of basalt. Seismic tomography studies have detected widespread fast anomalies in the mantle transition zone (MTZ) and lower mantle around the circum-Pacific and the Mediterranean region. These anomalies have been interpreted as stagnant oceanic lithosphere materials as these regions are closely associated with subduction zones, where the oceanic lithosphere plunges deeply into the MTZ. However, experimental studies on the phase transformations of harzburgite have been very limited, and no experimental studies have been conducted on the physical properties of harzburgite under MTZ conditions. In this study, we conducted high-temperature and high-pressure experiments, using a 1000-ton Kawai-type multi-anvil apparatus at GPMR, on a natural harzburgite at 14.1-24.2 GPa and 1473-1673 K. At 1673 K, harzburgite transformed to wadsleyite + garnet + clinopyroxene below 19 GPa and further decomposed into an assemblage of ringwoodite + garnet + stishovite above 20 GPa. Some amounts of akimotoite were produced at still higher pressures (22-23 GPa), and finally perovskite and magnesiowustite were found to coexist with garnet at 24.2 GPa. -

Geochemistry

GEOCHEMISTRY “Structure & Composition of the Earth” (M.Sc. Sem IV) Shekhar Assistant Professor Department of Geology Patna Science College Patna University E-mail: [email protected] Mob: +91-7004784271 Structure of the Earth • Earth structure and it’s composition is the essential component of Geochemistry. • Seismology is the main tool for the determination of the Earth’s interior. • Interpretation of the property is based on the behaviour of two body waves travelling within the interior. Structure of the Earth Variation in seismic body-wave paths, which in turn represents the variation in properties of the earth’s interior. Structure of the Earth Based on seismic data, Earth is broadly divided into- i. The Crust ii. The Mantle iii. The Core *Figure courtesy Geologycafe.com Density, Pressure & Temperature variation with Depth *From Bullen, An introduction to the theory of seismology. Courtesy of Cambridge Cambridge University Press *Figure courtesy Brian Mason: Principle of Geochemistry The crust • The crust is the outermost layer of the earth. • It consist 0.5-1.0 per cent of the earth’s volume and less than 1 per cent of Earth’s mass. • The average density is about “2.7 g/cm3” (average density of the earth is 5.51 g/cm³). • The crust is differentiated into- i) Oceanic crust ii) Continental crust The Oceanic crust • Covers approx. ~ 70% of the Earth’s surface area. • Average thickness ~ 6km (~4km at MOR : ~10km at volcanic plateau) • Mostly mafic in nature. • Relatively younger in age. The Oceanic crust Seismic study shows layered structural arrangement. - Seawater - Sediments - Basaltic layer - Gabbroic layer *Figure courtesy W.M.White: Geochemistry The Continental crust • Heterogeneous in nature. -

Crystal Structures of Minerals in the Lower Mantle

6 Crystal Structures of Minerals in the Lower Mantle June K. Wicks and Thomas S. Duffy ABSTRACT The crystal structures of lower mantle minerals are vital components for interpreting geophysical observations of Earth’s deep interior and in understanding the history and composition of this complex and remote region. The expected minerals in the lower mantle have been inferred from high pressure‐temperature experiments on mantle‐relevant compositions augmented by theoretical studies and observations of inclusions in natural diamonds of deep origin. While bridgmanite, ferropericlase, and CaSiO3 perovskite are expected to make up the bulk of the mineralogy in most of the lower mantle, other phases such as SiO2 polymorphs or hydrous silicates and oxides may play an important subsidiary role or may be regionally important. Here we describe the crystal structure of the key minerals expected to be found in the deep mantle and discuss some examples of the relationship between structure and chemical and physical properties of these phases. 6.1. IntrODUCTION properties of lower mantle minerals [Duffy, 2005; Mao and Mao, 2007; Shen and Wang, 2014; Ito, 2015]. Earth’s lower mantle, which spans from 660 km depth The crystal structure is the most fundamental property to the core‐mantle boundary (CMB), encompasses nearly of a mineral and is intimately related to its major physical three quarters of the mass of the bulk silicate Earth (crust and chemical characteristics, including compressibility, and mantle). Our understanding of the mineralogy and density, -

Spin Transition of Fe2+ in Ringwoodite (Mg,Fe)2Sio4 at High Pressures

American Mineralogist, Volume 98, pages 1803–1810, 2013 2+ Spin transition of Fe in ringwoodite (Mg,Fe)2SiO4 at high pressures IGOR S. LYUBUTIN1, JUNG-FU LIN2, ALEXANDER G. GAVRILIUK1,3,*, ANNA A. MIRONOVICH3, ANNA G. IVANOVA1, VLADIMIR V. RODDATIS4 AND ALEXANDER L. VASILIEV1,4 1Shubnikov Institute of Crystallography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow 119333, Russia 2Department of Geological Sciences, Jackson School of Geosciences, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712-0254, U.S.A. 3Institute for Nuclear Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, 60-letiya Oktyabrya prospekt 7a, Moscow 117312, Russia 4National Scientific Center, “Kurchatov Institute,” Moscow 123098, Russia ABSTRACT Electronic spin transitions of iron in the Earth’s mantle minerals are of great interest to deep-Earth researchers because their effects on the physical and chemical properties of mantle minerals can significantly affect our understanding of the properties of the deep planet. Here we have studied the electronic spin states of iron in ringwoodite (Mg0.75Fe0.25)2SiO4 using synchrotron Mössbauer spec- troscopy in a diamond-anvil cell up to 82 GPa. The starting samples were analyzed extensively using transmission and scanning electron microscopes to investigate nanoscale crystal chemistry and local iron distributions. Analyses of the synchrotron Mössbauer spectra at ambient conditions reveal two 2+ 2+ non-equivalent iron species, (Fe )1 and (Fe )2, which can be attributed to octahedral and tetrahedral sites in the cubic spinel structure, respectively. High-pressure Mössbauer measurements show the disappearance of the hyperfine quadrupole splitting (QS) of the Fe2+ ions in both sites at approximately 45–70 GPa, indicating an electronic high-spin (HS) to low-spin (LS) transition. -

Whole-Mantle Convection and the Transition-Zone Water Filter

hypothesis Whole-mantle convection and the transition-zone water filter David Bercovici & Shun-ichiro Karato Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, PO Box 208109, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8109, USA ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Because of their distinct chemical signatures, ocean-island and mid-ocean-ridge basalts are traditionally inferred to arise from separate, isolated reservoirs in the Earth’s mantle. Such mantle reservoir models, however, typically satisfy geochemical constraints, but not geophysical observations. Here we propose an alternative hypothesis that, rather than being divided into isolated reservoirs, the mantle is filtered at the 410-km-deep discontinuity. We propose that, as the ascending ambient mantle (forced up by the downward flux of subducting slabs) rises out of the high-water-solubility transition zone (between the 660 km and 410 km discontinuities) into the low-solubility upper mantle above 410 km, it undergoes dehydration-induced partial melting that filters out incompatible elements. The filtered, dry and depleted solid phase continues to rise to become the source material for mid-ocean-ridge basalts. The wet, enriched melt residue may be denser than the surrounding solid and accordingly trapped at the 410 km boundary until slab entrainment returns it to the deeper mantle. The filter could be suppressed for