Stanley Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0151 515 1846 Collection Redrow.Co.Uk/Woolton Fields

BEACONSFIELD ROAD, WOOLTON L25 6EE 0151 515 1846 COLLECTION REDROW.CO.UK/WOOLTON FIELDS BOWRING PARK A5047 BROADGREEN A5080 M62 A5080 M62 B5179 A5178 A5058 Directions A5178 M62 B A R WAVERTREE N H A M From the North/South/East/West D R IV E A5178 At Bryn Interchange take the second exit onto the M6 ramp A5178 to Warrington/ St Helens. Merge ontoB5179 M6. At Junction 21A, CHILDWALL exit onto M62 toward Liverpool. Continue onto A5080, keep A5058 G A T E A C R E left and stay on Bowring Park Road / A5080. Turn left onto P A R K D R I Queens Drive. Take the A5058 (South) ramp and merge onto V E BELLE VALE Queens Drive/ A5058. At the roundabout, take the thirdA562 exit ETHERLEY N G and stay on A5058. At the next roundabout take the first exit R A N G E B L 5 COLLECTION A 1 N 8 0 E onto Menlove Avenue / A562. Turn left onto Beaconsfield ATEACRE G D W A O O O LT R E O N N R LE A O L AD N DA E E N R G Road. The development is on the left. D RO OA R S S HE O CR S ID B5 U 17 R 1 D H D A A L From Liverpool / A5047 O E R W A WO D O A L OLTON HILL RO L O L L E I D R H T R T O R O B N A A562 A E 5 H 1 A D V AN 8 B 0 E L N 5 EFTON PARK 1 S SE U Turn right into Irvine Street, continue onto Wavertree Road/ 7 E D A 1 RO O R D EL SFI N O C EA B Q B5178. -

Post-Medieval and Modern Resource Assessment

THE SOLENT THAMES RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT POST-MEDIEVAL AND MODERN PERIOD (AD 1540 - ) Jill Hind April 2010 (County contributions by Vicky Basford, Owen Cambridge, Brian Giggins, David Green, David Hopkins, John Rhodes, and Chris Welch; palaeoenvironmental contribution by Mike Allen) Introduction The period from 1540 to the present encompasses a vast amount of change to society, stretching as it does from the end of the feudal medieval system to a multi-cultural, globally oriented state, which increasingly depends on the use of Information Technology. This transition has been punctuated by the protestant reformation of the 16th century, conflicts over religion and power structure, including regicide in the 17th century, the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions of the 18th and early 19th century and a series of major wars. Although land battles have not taken place on British soil since the 18th century, setting aside terrorism, civilians have become increasingly involved in these wars. The period has also seen the development of capitalism, with Britain leading the Industrial Revolution and becoming a major trading nation. Trade was followed by colonisation and by the second half of the 19th century the British Empire included vast areas across the world, despite the independence of the United States in 1783. The second half of the 20th century saw the end of imperialism. London became a centre of global importance as a result of trade and empire, but has maintained its status as a financial centre. The Solent Thames region generally is prosperous, benefiting from relative proximity to London and good communications routes. The Isle of Wight has its own particular issues, but has never been completely isolated from major events. -

Anfield Bicycle Club Annual Report

ANFIELD BICYCLE CLUB. FORMED 1879. W REPORT AND ACCOUNTS © AnfieldFOR BicycleTHE Club YEAR ENDING 3lst DECEMBER, I906. © Anfield Bicycle Club ANFIELD BICYCLE CLUB. FORMED 1879. w REPORT AND ACCOUNTS © AnfieldFOR BicycleTHE Club YEAR ENDING 31st DECEMBER, 1906. r © Anfield Bicycle Club CONTENTS. Names of Officers and Committee ... ... ... -1 Secretaries Reports ... ... ... ... 5—18 Accounts for 1906 19 Minutes of Annual General Meeting, held 8th January, 1907 20—23 Rules 24-28 Prize List, Rules, etc. ... ... ... 29—36 © Anfield Bicycle Club List of Members ... ... 37—39 ^X OFFICERS Kek, For 1907. President: Mr. W. R. TQFT. Vice-Presidents: Mr. G. B. MERCER. | Mr. E. G. WORTH. Captain : Mr. H. POOLE. Sub-Captains : Mr. E. J. COOV. | Mr. N. M. HIGHAM. Hon. Treasurer: Mr. W. M. OWEN, 40 Karslake Road, Seftoii Park, Liverpool. Committee : Mr. ,l. C. BAND. Mr. E. EDWARDS. „ E. A. BENTLET, „ R. L. L. KNIPE (resigned). „ E. BUCKLEY. „ S. J. LANCASTER. ., T. B. CONWAY. „ A. McCALL Mil. H. PHITCHARI). Hon. Secretary: .Mr. H. W. KEIZER, 70 Falkland Road, Egremoiit, Cheshire. © AnfieldAuditors Bicycle: Club Mr. D. R. FELL. I Mr. J. LOWENTHAL. Delegates: H.U.A.—Messrs. P. C. BEARDWOOD and H. W. KEIZER. N.R.R.A.—Messrs. N. M. HICHAM and H. W. KEIZER. ANFIELD BICYCLE CLUB. >—-e HON. SECRETARY'S REPORT, Presented at the Annual General Meeting- of the Members on Tuesday, the 8th January, 1907. Mr. Chairman and Gentlemen, I have much pleasure in submitting- the Report of the Club doings, other than racing, for 1906. The year may be described as a successful one. The runs have been fairly well attended, whilst the Bank Holiday fixtures, favoured by glorious weather, brought out quite exceptional musters. -

Flaybrick Cemetery CMP Volume2 17Dec18.Pdf

FLAYBRICK MEMORIAL GARDENS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VOLUME TWO: ANALYSIS DECEMBER 2018 Eleanor Cooper On behalf of Purcell ® 29 Marygate, York YO30 7WH [email protected] www.purcelluk.com All rights in this work are reserved. No part of this work may be Issue 01 reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means March 2017 (including without limitation by photocopying or placing on a Wirral Borough Council website) without the prior permission in writing of Purcell except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Issue 02 Patents Act 1988. Applications for permission to reproduce any part August 2017 of this work should be addressed to Purcell at [email protected]. Wirral Borough Council Undertaking any unauthorised act in relation to this work may Issue 03 result in a civil claim for damages and/or criminal prosecution. October 2017 Any materials used in this work which are subject to third party Wirral Borough Council copyright have been reproduced under licence from the copyright owner except in the case of works of unknown authorship as Issue 04 defined by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Any January 2018 person wishing to assert rights in relation to works which have Wirral Borough Council been reproduced as works of unknown authorship should contact Purcell at [email protected]. Issue 05 March 2018 Purcell asserts its moral rights to be identified as the author of Wirral Borough Council this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Consultation Draft Purcell® is the trading name of Purcell Miller Tritton LLP. -

Robert Hodgins

St Peter’s Church, Formby Review of the Ten Commonwealth War Graves in the Graveyard Prepared to mark the VE Day Celebrations 08-10 May 2020 Introduction This review has been prepared to commemorate the ten graves in the graveyard that meet the published criteria of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) which honours the 1.7 million men and women who died in the armed forces of the British Empire during the First and Second World Wars, and ensures they will never be forgotten. The CWGC work began with building, and now maintaining, cemeteries and memorials at 23,000 locations in more than 150 countries and territories and managing the official casualty database archives for their member nations. The CWGC core principles, articulated in their Royal Charter in 1917, are as relevant now as they were over a hundred years ago: • Each of the Commonwealth dead should be commemorated by name on a headstone or memorial • Headstones and memorials should be permanent • Headstones should be uniform • There should be equality of treatment for the war dead irrespective of rank or religion. CWGC are responsible for the commemoration of: • Personnel who died between 04 August 1914 and 31 August 1921; and between 03 September 1939 and 31 December 1947 whilst serving in a Commonwealth military force or specified auxiliary organisation. • Personnel who died between 04 August 1914 and 31 August 1921; and between 03 September 1939 and 31 December 1947 after they were discharged from a Commonwealth military force, if their death was caused by their wartime service. • Commonwealth civilians who died between 03 September 1939 and 31 December 1947 as a consequence of enemy action, Allied weapons of war or whilst in an enemy prison camp. -

Official E-Programme

OFFICIAL E-PROGRAMME Versus Castleford Tigers | 16 August 2020 Kick-off 4.15pm 5000 BETFRED WHERE YOU SEE AN CONTENTS ARROW - CLICK ME! 04 06 12 View from the Club Roby on his 500th appearance Top News 15 24 40 Opposition Heritage Squads SUPER LEAGUE HONOURS: PRE–SUPER LEAGUE HONOURS: Editor: Jamie Allen Super League Winners: 1996, 1999, Championship: 1931–32, 1952–53, Contributors: Alex Service, Bill Bates, 2000, 2002, 2006, 2014, 2019 1958–59, 1965–66, 1969–70, 1970–71, Steve Manning, Liam Platt, Gary World Club Challenge Honours: 1974–75 Wilton, Adam Cotham, Mark Onion, St. Helens R.F.C. Ltd 2001, 2007 Challenge Cup: 1955–56, 1960–61, Conor Cockroft. Totally Wicked Stadium, Challenge Cup Honours: 1996, 1997, 1965–66, 1971–72, 1975–76 McManus Drive, 2001, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008 Leaders’ Shield: 1964–65, 1965–66 Photography: Bernard Platt, Liam St Helens, WA9 3AL BBC Sports Team Of The Year: 2006 Regal Trophy: 1987–88 Platt, SW Pix. League Leaders’ Shield: 2005, 2006, Premiership: 1975–76, 1976–77, Tel: 01744 455 050 2007, 2008, 2014, 2018, 2019 1984–85, 1992–93 Fax: 01744 455 055 Lancashire Cup: 1926–27, 1953–54, Ticket Hotline: 01744 455 052 1960–61, 1961–62, 1962–63, 1963–64, Email: [email protected] 1964–65, 1967–68, 1968–69, 1984–85, Web: www.saintsrlfc.com 1991–92 Lancashire League: 1929–30, Founded 1873 1931–32, 1952–53, 1959–60, 1963–64, 1964–65, 1965–66, 1966–67, 1968–69 Charity Shield: 1992–93 BBC2 Floodlit Trophy: 1971–72, 1975–76 3 VIEW FROM THE CLUB.. -

Coach Welcome Scheme

Coach welcome scheme LIVERPOOL COACH WELCOME There is secure coach parking at the Eco Coach groups can register for a special Visitor Centre alongside the park and ride Coach Welcome, which involves a personal scheme. This includes lounge, kitchen welcome to the city of Liverpool from one and shower facilities for drivers. of our enthusiastic coach hosts, the latest For more information visit www.visitsouthport.com information on what’s on, complimentary or contact Steve Christian on +44 (0)151 934 2319 maps, rest room and refreshment facilities. For drivers, there are coach drop-off WIRRAL COACH WELCOME and pick-up facilities, parking and traffic For a Mersey Ferries river cruise, park at information and refreshments. Woodside Ferry Terminal. Mersey Ferries links There are two locations: Liverpool Cathedral a number of exciting waterfront attractions in the city’s historic Hope Street Quarter, in Liverpool and Wirral, enabling you to and at Liverpool ONE bus station. create flexible days out for your group. We recommend booking at least 10 days in advance. Port Sunlight, a fascinating 19th century garden • LIVERPOOL CATHEDRAL village, is a very popular group travel destination +44 (0)151 702 7284 and home to both the Port Sunlight Museum and [email protected] Lady Lever Art Gallery. There is extensive free coach parking adjacent to the Lady Lever Art Gallery, with • LIVERPOOL ONE BUS STATION the village attractions easily accessible on foot. +44 (0)151 330 1354 [email protected] For more information about these and more visit www.visitwirral.com/visitor-info/group-travel SOUTHPORT COACH WELCOME Coach hosts are available from April to October to meet and greet coach visitors disembarking at the coach drop-off point on Lord Street, adjacent to The Atkinson. -

Student Guide to Living in Liverpool

A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL www.hope.ac.uk 1 LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL CONTENTS THIS IS LIVERPOOL ........................................................ 4 LOCATION ....................................................................... 6 IN THE CITY .................................................................... 9 LIVERPOOL IN NUMBERS .............................................. 10 DID YOU KNOW? ............................................................. 11 OUR STUDENTS ............................................................. 12 HOW TO LIVE IN LIVERPOOL ......................................... 14 CULTURE ....................................................................... 17 FREE STUFF TO DO ........................................................ 20 FUN STUFF TO DO ......................................................... 23 NIGHTLIFE ..................................................................... 26 INDEPENDENT LIVERPOOL ......................................... 29 PLACES TO EAT .............................................................. 35 MUSIC IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 40 PLACES TO SHOP ........................................................... 45 SPORT IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 50 “LIFE GOES ON SPORT AT HOPE ............................................................. 52 DAY AFTER DAY...” LIVING ON CAMPUS ....................................................... 55 CONTACT -

Arthur Atkinson

Arthur Atkinson Arthur Atkinson was born on April 5,1906 at 12 Alfred Street, Castleford, just off Wheldon Road, where the now demolished Nestle's factory used to be. The 1911 Census however shows the family residing in Radcliffe, Lancashire and Arthur, then aged 5, at school there. Fortunately for Castleford fans however Arthur, at least, returned to Castleford. Legend has it that Arthur was behind the posts one day at Castleford's old ground at Sandy Desert, Lock Lane, when he fielded the ball and with expert ease punted or drop-kicked it back into the field of play and that a certain Mr Walter Smith saw a potential star in the making. Arthur signed for the club in 1926 as they made their introduction into the Rugby Football League and made his debut for the first team in their fifth match, away at Rochdale, on Saturday 11 September, 1926 when they lost 33-5. Arthur quickly made his mark in the side and scored his first try against Halifax the following month although Cas were destined to finish bottom of the league in their first season. Displaying strong qualities of leadership at an early age, he was appointed captain in the 1928-29 season, a role he retained until his retirement in 1942. His form that season alerted selectors to his abilities and he made his debut for Yorkshire, becoming the first Castleford player to gain such an honour, in the game against Glamorgan and Monmouth at Cardiff, going on to earn 14 caps for his county and became Castleford's first full international in that same season, eventually playing six times for England and ten times for Great Britain, including two tours to Australasia, for whom he scored five tries, and there were clear signs of what was to come as the team reached the semi final of the Challenge Cup, the first year that the final was to be played at Wembley. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

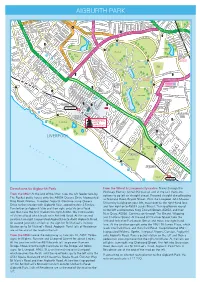

Aigburth Park

G R N G A A O A T D B N D LM G R R AIGBURTHA PARK 5 P R I R M B T 5 R LTAR E IN D D GR G 6 R 1 I Y CO O Superstore R R O 5 V Y 7 N D 2 R S E 5 E E L T A C L 4 A Toxteth Park R E 0 B E P A E D O Wavertree H S 7 A T A L S 8 Cemetery M N F R O Y T A Y E A S RM 1 R N Playground M R S P JE N D K V 9 G E L A IC R R K E D 5 OV N K R R O RW ST M L IN E O L A E O B O A O P 5 V O W IN A U C OL AD T R D A R D D O E A S S 6 P N U E Y R U B G U E E V D V W O TL G EN T 7 G D S EN A V M N N R D 1 7 I B UND A A N E 1 N L A 5 F R S V E B G G I N L L S E R D M A I T R O N I V V S R T W N A T A M K ST E E T V P V N A C Y K V L I V A T A D S R G K W I H A D H K A K H R T C N F I A R W IC ID I A P A H N N R N L L E A E R AV T D E N W S S L N ARDE D A T W D T N E A G K A Y GREENH H A H R E S D E B T B E M D T G E L M O R R Y O T V I N H O O O A D S S I T L M L R E T A W V O R K E T H W A T C P U S S R U Y P IT S T Y D C A N N R I O C H R C R R N X N R RL T E TE C N A DO T E E N TH M 9 A 56 G E C M O U 8 ND R S R R N 0 2 A S O 5 R B L E T T D R X A A L O R BE E S A R P M R Y T Y L A A C U T B D H H S M K RT ST S E T R O L E K I A H N L R W T T H D A L RD B B N I W A LA 5175 A U W I R T Y P S R R I F H EI S M S O Y C O L L T LA A O D O H A T T RD K R R H T O G D E N D L S S I R E DRI U V T Y R E H VE G D A ER E H N T ET A G L Y R EFTO XT R E V L H S I S N DR R H D E S G S O E T T W T H CR E S W A HR D R D Y T E N V O D U S A O M V B E N I O I IR R S N A RIDG N R B S A S N AL S T O T L D K S T R T S V T O R E T R E O A R EET E D TR K A D S LE T T E P E TI S N -

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project December 2011 Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project Museum of Liverpool Pier Head Liverpool L3 1DG © Trustees of National Museums Liverpool and English Heritage 2011 Contents Introduction to Historic Settlement Study..................................................................1 Aigburth....................................................................................................................4 Allerton.....................................................................................................................7 Anfield.................................................................................................................... 10 Broadgreen ............................................................................................................ 12 Childwall................................................................................................................. 14 Clubmoor ............................................................................................................... 16 Croxteth Park ......................................................................................................... 18 Dovecot.................................................................................................................. 20 Everton................................................................................................................... 22 Fairfield .................................................................................................................