Lady in the Dark and Each Spoofs a Style of Operetta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francis Poulenc

CHAN 3134(2) CCHANHAN 33134134 WWideide bbookook ccover.inddover.indd 1 330/7/060/7/06 112:43:332:43:33 Francis Poulenc © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht The Carmelites Francis Poulenc © Stephen Vaughan © Stephen CCHANHAN 33134(2)134(2) BBook.inddook.indd 22-3-3 330/7/060/7/06 112:44:212:44:21 Francis Poulenc (1899 – 1963) The Carmelites Opera in three acts Libretto by the composer after Georges Bernanos’ play Dialogues des Carmélites, revised English version by Joseph Machlis Marquis de la Force ................................................................................ Ashley Holland baritone First Commissioner ......................................................................................James Edwards tenor Blanche de la Force, his daughter ....................................................... Catrin Wyn-Davies soprano Second Commissioner ...............................................................................Roland Wood baritone Chevalier de la Force, his son ............................................................................. Peter Wedd tenor First Offi cer ......................................................................................Toby Stafford-Allen baritone Thierry, a valet ........................................................................................... Gary Coward baritone Gaoler .................................................................................................David Stephenson baritone Off-stage voice ....................................................................................... -

Critical Perspectives on American Musical Theatre Thea

Critical Perspectives on American Musical Theatre Thea. 80200, Spring 2002 David Savran, CUNY Feb 4—Introduction: One Singular Sensation To be read early in the semester: DiMaggio, “Cultural Boundaries and Structural Change: The Extension of the High Culture Model to Theater, Opera, and the Dance, 1900-1940;” Block, “The Broadway Canon from Show Boat to West Side Story and the European Operatic Ideal;” Savran, “Middlebrow Anxiety” 11—Kern, Hammerstein, Ferber, Show Boat Mast, “The Tin-Pan-Tithesis of Melody: American Song, American Sound,” “When E’er a Cloud Appears in the Blue,” Can’t Help Singin’; Berlant, “Pax Americana: The Case of Show Boat;” 18—No class 20—G. and I. Gershwin, Bolton, McGowan, Girl Crazy; Rodgers, Hart, Babes in Arms ***Andrea Most class visit*** Most, Chapters 1, 2, and 3 of her manuscript, “We Know We Belong to the Land”: Jews and the American Musical Theatre; Rogin, Chapter 1, “Uncle Sammy and My Mammy” and Chapter 2, “Two Declarations of Independence: The Contaminated Origins of American National Culture,” in Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot; Melnick, “Blackface Jews,” from A Right to Sing the Blues: African Americans, Jews, and American Popular Song 25— G. and I. Gershwin, Kaufman, Ryskind, Of Thee I Sing, Shall We Dance Furia, “‘S’Wonderful: Ira Gershwin,” in his Poets of Tin Pan Alley, Mast, “Pounding on Tin: George and Ira Gershwin;” Roost, “Of Thee I Sing” Mar 4—Porter, Anything Goes, Kiss Me, Kate Furia, “The Tinpantithesis of Poetry: Cole Porter;” Mast, “Do Do That Voodoo That You Do So Well: Cole Porter;” Lawson-Peebles, “Brush Up Your Shakespeare: The Case of Kiss Me Kate,” 11—Rodgers, Hart, Abbott, On Your Toes; Duke, Gershwin, Ziegfeld Follies of 1936 Furia, “Funny Valentine: Lorenz Hart;” Mast, “It Feels Like Neuritis But Nevertheless It’s Love: Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart;” Furia, Ira Gershwin: The Art of the Lyricist, pages 125-33 18—Berkeley, Gold Diggers of 1933; Minnelli, The Band Wagon Altman, The American Film Musical, Chaps. -

SMTA Catalog Complete

The Integrated Broadway Library Index including the complete works from 34 collections: sorted by musical HL The Singer's Musical Theatre Anthology (22 vols) A The Singer's Library of Musical Theatre (8 vols) TMTC The Teen's Musical Theatre Collection (2 vols) MTAT The Musical Theatre Anthology for Teens (2 vols) Publishers: HL = Hal Leonard; A = Alfred *denotes a song absent in the revised edition Pub Voice Vol Page Song Title Musical Title HL S 4 161 He Plays the Violin 1776 HL T 4 198 Mama, Look Sharp 1776 HL B 4 180 Molasses to Rum 1776 HL S 5 246 The Girl in 14G (not from a musical) HL Duet 1 96 A Man and A Woman 110 In The Shade HL B 5 146 Gonna Be Another Hot Day 110 in the Shade HL S 2 156 Is It Really Me? 110 in the Shade A S 1 32 Is It Really Me? 110 in the Shade HL S 4 117 Love, Don't Turn Away 110 in the Shade A S 1 22 Love, Don't Turn Away 110 in the Shade HL S 1 177 Old Maid 110 in the Shade HL S 2 150 Raunchy 110 in the Shade HL S 2 159 Simple Little Things 110 in the Shade A S 1 27 Simple Little Things 110 in the Shade HL S 5 194 Take Care of This House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue A T 2 41 Dames 42nd Street HL B 5 98 Lullaby of Broadway 42nd Street A B 1 23 Lullaby of Broadway 42nd Street HL T 3 200 Coffee (In a Cardboard Cup) 70, Girls, 70 HL Mezz 1 78 Dance: Ten, Looks: Three A Chorus Line HL T 4 30 I Can Do That A Chorus Line HL YW MTAT 120 Nothing A Chorus Line HL Mezz 3 68 Nothing A Chorus Line HL Mezz 4 70 The Music and the Mirror A Chorus Line HL Mezz 2 64 What I Did for Love A Chorus Line HL T 4 42 One More Beautiful -

Assisted by Katie Rowan, Accompanist

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Morgan Robertson & Ellie Wise Junior Voice Recital assisted by Katie Rowan, Accompanist Tuesday, April 9, 2013 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert. Please turn off all pagers and cell phones. PROGRAM I Wish It So from Juno Marc Blitzstein • 1905 - 1964 My Ship from Lady in the Dark Kurt Weill • 1900 - 1950 Ira Gershwin • 1896 - 1983 Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Out There from Hunchback of Notre Dame Stephen Schwarts • b. 1948 Alan Menken • b. 1949 There Won’t Be Trumpets from Anyone Can Whistle Stephen Sondhiem • b. 1930 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Take Me to the World from Evening Primrose Stephen Sondheim The Girls of Summer from Marry Me a Little Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Glamorous Life from A Little Night Music Stephen Sondheim My New Philosophy from You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown Clark Gesner • 1938 - 2002 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Mr. Snow from Carousel Richard Rodgers • 1902 - 1979 Oscar Hammerstein II • 1895 - 1960 Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist My Party Dress from Henry and Mudge Kait Kerrigan • b. 1981 Brian Loudermilk • b. 1983 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist INTERMISSION Always a Bridesmaid from I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change Jimmy Roberts Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Music and the Mirror from A Chorus Line Joe DiPietro • b. -

99 Stat. 288 Public Law 99-86—Aug. 9, 1985

99 STAT. 288 PUBLIC LAW 99-86—AUG. 9, 1985 Public Law 99-86 99th Congress Joint Resolution To provide that a special gold medal honoring George Gershwin be presented to his Aug. 9, li>a5 sister, Frances Gershwin Godowsky, and a special gold medal honoring Ira Gersh- [H.J. Res. 251] win be presented to his widow, Leonore Gershwin, and to provide for the production of bronze duplicates of such medals for sale to the public. Whereas George and Ira Gershwin, individually and jointly, created music which is undeniably American and which is internationally admired; Whereas George Gershwin composed works acclaimed both as classi cal music and as popular music, including "Rhapsody in Blue", "An American in Paris", "Concerto in F", and "Three Preludes for Piano"; Whereas Ira Gershwin won a Pulitzer Prize for the lyrics for "Of Thee I Sing", the first lyricist ever to receive such prize; Whereas Ira Gershwin composed the lyrics for major Broadway productions, including "A Star is Born", "Lady in the Dark", "The Barkleys of Broadway", and for hit songs, including "I Can't Get Started", "Long Ago and Far Away", and "The Man That Got Away"; Whereas George and Ira Gershwin collaborated to compose the music and lyrics for major Broadway productions, including "Lady Be Good", "Of Thee I Sing", "Strike Up the Band", "Oh Kay!", and "Funny Face"; Whereas George and Ira Gershwin collaborated to produce the opera "Porgy and Bess" and the 50th anniversary of its first perform ance will occur during 1985; Whereas George and Ira Gershwin collaborated to compose -

Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding Also Provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 839 CS 508 906 AUTHOR Carr, John C. TITLE "Crazy for You." Spotlight on Theater Notes. INSTITUTION John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE [95] NOTE 17p.; Produced by the Performance Plus Program, Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding also provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund. For other guides in this series, see CS 508 902-905. PUB TYPE Guides General (050) EDRS PRTCE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Acting; *Cultural Enrichment; *Drama; Higher Education; Playwriting; Popular Culture; Production Techniques; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Crazy for You; Historical Background; Musicals ABSTRACT This booklet presents a variety of materials concerning the musical play "Crazy for You," a recasting of the 1930 hit. "Girl Crazy." After a brief historical introduction to the musical play. the booklet presents biographical information on composers George and Ira Gershwin, the book writer, the director, the star choreographer, various actors in the production, the designers, and the musical director. The booklet also offers a quiz about plays. and a 7-item list of additional readings. (RS) ....... ; Reproductions supplied by EDRS ore the best that can he made from the original document, U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Ofi.co ofEaucabonni Research aria improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER IERIC1 Et This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization onqinallnq d 0 Minor charms have been made to improve reproduction quality. Points or view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent official OERI position or policy -1411.1tn, *.,3^ ..*. -

Weill, Kurt (Julian)

Weill, Kurt (Julian) (b Dessau, 2 March 1900; d New York, 3 April 1950). German composer, American citizen from 1943. He was one of the outstanding composers in the generation that came to maturity after World War I, and a key figure in the development of modern forms of musical theatre. His successful and innovatory work for Broadway during the 1940s was a development in more popular terms of the exploratory stage works that had made him the foremost avant- garde theatre composer of the Weimar Republic. 1. Life. Weill‟s father Albert was chief cantor at the synagogue in Dessau from 1899 to 1919 and was himself a composer, mostly of liturgical music and sacred motets. Kurt was the third of his four children, all of whom were from an early age taught music and taken regularly to the opera. Despite its strong Wagnerian emphasis, the Hoftheater‟s repertory was broad enough to provide the young Weill with a wide range of music-theatrical experiences which were supplemented by the orchestra‟s subscription concerts and by much domestic music-making. Weill began to show an interest in composition as he entered his teens. By 1915 the evidence of a creative bent was such that his father sought the advice of Albert Bing, the assistant conductor at the Hoftheater. Bing was so impressed by Weill‟s gifts that he undertook to teach him himself. For three years Bing and his wife, a sister of the Expressionist playwright Carl Sternheim, provided Weill with what almost amounted to a second home and introduced him a world of metropolitan sophistication. -

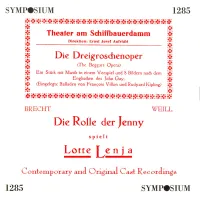

4601553-3Aa246-Booklet-SYMP1285

SYMPOSIUM RECORDS CD 1285 MUSIK IN DER WEIMAR REPUBLIK Brecht Die Dreigroschenoper Weill There is an interesting entry for Thursday, 27th September 1928 in Count Harry Kessler’s Diary of a Cosmopolitan, “In the evening saw Brecht’s Dreigroschenoper, music by Weill. A fascinating production, with rudimentary staging in the Piscator style. Weill’s music is catchy and expressive and the players (Harald Paulsen, Rosa Valetti, and so on) are excellent. It is the show of the season, always sold out: ‘You must see it!’”. Perhaps this diary note by an acute observer of the Berlin scene should be framed between two further references. In Before the Deluge, published in 1972, Otto Friedrich (an equally keen observer, he also wrote the introduction to the Kessler volume) commented laconically how “the opening night was a legendary triumph, and of every ten Berliners alive today, at least three claim to have been in the cheering audience”. Kessler’s editor comments that the work made Brecht’s name, and adds that “some of the tunes by Kurt Weill are still sung”. During the last part of the twentieth century, there was a growing interest in ‘rediscovering’ apparently neglected, or forgotten, music. Particular attention has been given to the genre attacked by the Nazis as “Entartete Musik” (degenerate music) of which the compositions of Weill were chosen as prime examples. In January 2000 the BBC celebrated the centenary of Weill’s birth and the fiftieth anniversary of his death by sponsoring a festival at the Barbican focusing on his less familiar works. Popular and media reception was rapturous. -

An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2011 An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill Elizabeth Rose Williamson Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Williamson, Elizabeth Rose, "An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill" (2011). Honors Theses. 2157. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2157 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION AND MUSICAL ADAPTATION IN VOCAL COMPOSITIONS OF KURT WEILL by Elizabeth Rose Williamson A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2011 Approved by Reader: Professor Corina Petrescu Reader: Professor Charles Gates I T46S 2^1 © 2007 Elizabeth Rose Williamson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the people of the Kurt Weill Zentrum in Dessau Gennany who graciously worked with me despite the reconstruction in the facility. They opened their resources to me and were willing to answer any and all questions. Thanks to Clay Terry, I was able to have an uproariously hilarious ending number to my recital with “Song of the Rhineland.” I thank Dr. Charles Gates for his attention and interest in my work. -

New Real Book: Vol

New Real Book: Vol. 2 Title Composer / As Played By Page 26-2 John Coltrane 398 500 Miles High Chick Corea & Neville Potter 104 Afro-Centric Joe Henderson 1 After The Rain John Coltrane 3 After You've Gone Creamer & Layton 5 Ain't Misbehavin' Fats Waller, Harry Brooks & Andy Razaf 6 Along Came Betty Benny Golson 7 Asa (The Zoo Blues) Djavan 9 Avance Russell Ferrante 11 Baby It's Cold Outside Frank Loesser 13 Baja Bajo John Pattitucci & Chick Corea 15 Bass Blues John Coltrane 17 Beauty And The Beast Wayne Shorter 20 Bessie's Blues John Coltrane 21 Black And Blue Fats Waller, Harry Brooks & Andy Razaf 22 Black Coffee Paul Francis Webster & Sonny Burke 23 Blues For Alice Charlie Parker 26 Blues For Yna Yna Gerald Wilson 27 Body and Soul E Heyman, R Sour, F Eyton & J Green 29 Bolivia Cedar Walton 34 The Boy Next Door Hugh Martin & Ralph Blane 34 Bye Bye Blackbird Ray Henderson & Mort Dixon 34 Cafe Egberto Gismonti 37 Capim Djavan 39 Casa Forte Edu Lobo 41 Central Park West John Coltrane 43 Charmed Circle Cedar Walton 45 Cherokee Ray Noble 47 A Child Is Born Thad Jones 346 Choices Mike Stern 49 Chromazone Mike Stern 51 Clockwise Cedar Walton 55 Cold Duck Time Eddie Harris 56 Criss Cross Ray Obiedo 57 Day By Day Sammy Cahn, Axel Stordahl & Paul Weston 60 Dear Lord John Coltrane 61 Dee Song Enrico Pieranunzi 63 Delgado Eddie Gomez 66 Detour Ahead Lou Carter, Herb Ellis & John Frigo 68 Devil May Care T.P. -

Songs by Artist

YouStarKaraoke.com Songs by Artist 602-752-0274 Title Title Title 1 Giant Leap 1975 3 Doors Down My Culture City Let Me Be Myself (Wvocal) 10 Years 1985 Let Me Go Beautiful Bowling For Soup Live For Today Through The Iris 1999 Man United Squad Loser Through The Iris (Wvocal) Lift It High (All About Belief) Road I'm On Wasteland 2 Live Crew The Road I'm On 10,000 MANIACS Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I M Gone Candy Everybody Wants Doo Wah Diddy When I'm Gone Like The Weather Me So Horny When You're Young More Than This We Want Some PUSSY When You're Young (Wvocal) These Are The Days 2 Pac 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Trouble Me California Love Landing In London 100 Proof Aged In Soul Changes 3 Doors Down Wvocal Somebody's Been Sleeping Dear Mama Every Time You Go (Wvocal) 100 Years How Do You Want It When You're Young (Wvocal) Five For Fighting Thugz Mansion 3 Doors Down 10000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Road I'm On Because The Night 2 Pac & Eminem Road I'm On, The 101 Dalmations One Day At A Time 3 LW Cruella De Vil 2 Pac & Eric Will No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 10CC Do For Love 3 Of A Kind Donna 2 Unlimited Baby Cakes Dreadlock Holiday No Limits 3 Of Hearts I'm Mandy 20 Fingers Arizona Rain I'm Not In Love Short Dick Man Christmas Shoes Rubber Bullets 21St Century Girls Love Is Enough Things We Do For Love, The 21St Century Girls 3 Oh! 3 Wall Street Shuffle 2Pac Don't Trust Me We Do For Love California Love (Original 3 Sl 10CCC Version) Take It Easy I'm Not In Love 3 Colours Red 3 Three Doors Down 112 Beautiful Day Here Without You Come See Me -

News and Events

Volume 15 Number 1 topical Weill Spring 1997 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news &news events The Royal National Theatre Ushers in Lady in the Dark &news events Opening Catherine Ashmore (right). Catherine Ashmore Scenes (left), Damm Photos: Van Then and Now . Gertrude Lawrence as Liza in 1941 Maria Friedman as Liza in 1997 (with Richard Hale). (with Hugh Ross). The production by Francesca Zambello is stylish, The show is original and appealing and, as heroines go, so is Maria Friedman. Her Liza Elliott stalks into her restrained, cerebral. Weill’s music is plangent and shrink’s eyrie radiating nervy, brittle assurance, then sinuous, a remarkable synthesis of Weimar jazz and spins rapturously off into the first of the dream- pre-Sondheim querulousness. Maria Friedman, sure- sequences that interrupt the more realistic proceed- ly confirmed now as our supreme musical actress, ings. Our own Tina Brown would have to be promot- negotiates her backward spiral with exuberant grace ed from the chair of the New Yorker to the throne of and wit, swirling in mists and ballgowns, defiantly zip- England to match a fantasy like that. ping on the Schiaparelli frock when she takes off with — Benedict Nightingale, “Freudian drama that does not a movie star hunk (the Victor Mature role is occupied shrink from emotion,” The Times (12 March 1997) by a suitably anaemic grinner, Steven Edward Moore) and even stepping daintily across a tightrope, in Adrianne Lobel has designed a conceptual setting of sail-like Stoppardian vein, to prove she is a “proponent of triangles which introduces a number of staging constraints.