Past, Present, and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marie-Odile SALATI, « E Trope of Passage in English Hours», Viatica

Pour citer cet article : Marie-Odile SALATI, « e Trope of Passage in English Hours», Viatica [En ligne], n°HS3, mis à jour le : 14/02/2020, URL : https://revues-msh.uca.fr:443/viatica/index.php?id=1213. Les articles de la revue Viatica sont protégés par les dispositions générales du Code de la propriété intellectuelle. Conditions d’utilisation : respect du droit d’auteur et de la propriété intellectuelle. Licence CC BY : attribution. L’Université Clermont Auvergne est l’éditeur de la revue en ligneViatica. The Trope of Passage in English Hours Marie-Odile SALATI LLSETI (EA 3706), Université Savoie Mont Blanc Abstract:This article suggests that the English Hours travel essays written in the 1870s were the crucible in which James perfected his technique of literary representation. Focusing on progress across space and tropes of liminality, the study highlights the presence, as of 1872, of the scenario of ghostly vision which dramatizes the shift from observation to reflection in the author’s fiction. It also shows how the 1877 essays mirror the novelist’s ethical concerns as he was working his way towards a poetical rendering of prosaic urban modernity. Keywords: Henry James, representation, realism, liminal space, spectrality Résumé : Cet article aborde les essais des années 1870 publiés dans English Hours comme le creuset dans lequel s’est élaborée la technique de représentation jamesienne. En analysant le parcours spatial et les lieux liminaux, il fait ressortir la mise en place, dès 1872, du scénario de vision spectrale figurant le passage de l’observation à la réflexion par le langage dans l’œuvre fictionnelle de l’auteur, et dans les récits de 1877, l’ouverture d’une voie permettant de concilier le prosaïsme de la réalité urbaine moderne et les exigences éthiques de l’art. -

Henry James , Edited by Daniel Karlin Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00398-9 — The Bostonians Henry James , Edited by Daniel Karlin Frontmatter More Information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00398-9 — The Bostonians Henry James , Edited by Daniel Karlin Frontmatter More Information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00398-9 — The Bostonians Henry James , Edited by Daniel Karlin Frontmatter More Information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES general editors Michael Anesko, Pennsylvania State University Tamara L. Follini, University of Cambridge Philip Horne, University College London Adrian Poole, University of Cambridge advisory board Martha Banta, University of California, Los Angeles Ian F. A. Bell, Keele University Gert Buelens, Universiteit Gent Susan M. Grifn, University of Louisville Julie Rivkin, Connecticut College John Carlos Rowe, University of Southern California Ruth Bernard Yeazell, Yale University Greg Zacharias, Creighton University © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00398-9 — The Bostonians Henry James , Edited by Daniel Karlin Frontmatter More Information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES 1 Roderick Hudson 23 A Landscape Painter and Other 2 The American Tales, 1864–1869 3 Watch and Ward 24 A Passionate Pilgrim and Other 4 The Europeans -

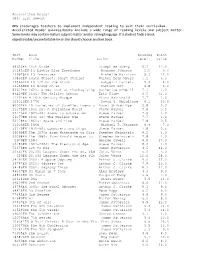

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Issn 0017-0615 the Gissing Journal

ISSN 0017-0615 THE GISSING JOURNAL “More than most men am I dependent on sympathy to bring out the best that is in me.” – George Gissing’s Commonplace Book. ***************************** Volume XXXIII, Number 4 October, 1997 ****************************** Contents The Forthcoming Gissing Conference: First Announcement 1 George Gissing, Henry James and the Concept of Realism, 2 by Janice Deledalle-Rhodes Gissing and the Paparazzi, by Francesco Badolato and 29 Pierre Coustillas “Far, Far Away”: George Gissing’s Passion for the Classics, 35 by Ayaka Okada Book Review, by William Greenslade 37 Notes and News 43 Recent Publications 47 -- 1 -- First Announcement Gissing Conference 9-11 September 1999 English Department, University of Amsterdam Spuistraat 210, 1012 VT Amsterdam The Netherlands Preparations are under way for an international Gissing Conference to be held at Amsterdam in the late summer of 1999. The organizers have gratefully accepted the offer made by the English Department in the University of Amsterdam to host this first major conference to focus on the works of the novelist, whose reappraisal has been intensified by and has greatly benefited from the recently completed publication of his collected correspondence. The conference will be held at the newly restored Doelenzaal, a splendid example of seventeenth-century Dutch architecture, in the heart of the old city. Within walking distance are some of the world’s greatest art collections, housed in the Rijksmuseum, the Municipal museum and the Van Gogh museum. The members of the organizing Committee are: Prof. Martha S. Vogeler (USA), Prof. Jacob Korg (USA), Prof. Pierre Coustillas (France), Dr. David Grylls (England) and Drs. -

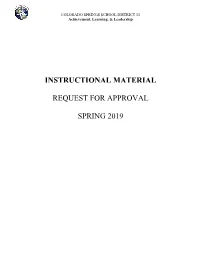

Instructional Material Request for Approval

COLORADO SPRINGS SCHOOL DISTRICT 11 Achievement, Learning, & Leadership INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIAL REQUEST FOR APPROVAL SPRING 2019 BOARD OF EDUCATION INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS APPROVAL REPORT Supplemental Materials - Elementary School Grade Title Notes/Description Author Content Area Min/Max The DBQ Project Elementary Mini-Qs Vol. 1 Roden, Brady, Winter, Adams, & Kent Units include history, literature, civics, science, and math. Copyright 2019 English/ K 5 All units include literacy. Each unit contains a hook Language Arts activity, a background essay, primary and secondary Social Studies source documents, and comprehension questions. At the Science end, all students write an essay where they have to use evidence for their writing. Standards: History, Reading, Writing, and Communicating. Submitted by: Anne Weaver, Martinez Elementary. BOARD OF EDUCATION INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS APPROVAL REPORT Core Materials - Middle School Grade Title Notes/Description Author Content Area Min/Max A Christmas Carol Dickens, Charles A Christmas Carol tells the story of a bitter old miser Copyright 2015 Reading/English/ 6 12 named Ebenezer Scrooge and his transformation into a Language Arts gentler, kindlier man after visitations by the ghost of his former business partner Jacob Marley and the ghosts of Christmases past, present and yet to come. Standards: Oral Expression and Listening, Reading for All Purposes, Writing and Composition, and Research Inquiry and Design. Submitted by: Dr. Shelmon Brown, English Language Arts Facilitator. A Doll's House Ibsen, Henrick A Doll's House is a three-act play in prose by Henrik Copyright 2018 Reading/English/ 6 12 Ibsen. It premiered at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, Language Arts Denmark, on 21 December 1879, having been published earlier that month. -

Chapter 5 Progress

Tuberculosis and Disabled Identity in Nineteenth-Century Literature: Invalid Lives Item Type Book Authors Tankard, Alex Citation Tankard, A. (2018). Tuberculosis and Disabled Identity in Nineteenth-Century Literature: Invalid Lives. London: Palgrave Macmillan. DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-71446-2 Publisher Palgrave Macmillan Download date 29/09/2021 04:09:28 Item License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/621467 Chapter 5 Progress: Valid Invalid Identity in Ships That Pass in the Night (1893) Introduction Wuthering Heights ridiculed consumptive stereotypes, and Jude the Obscure exposed socioeconomic and cultural factors that disabled people with chronic illness, but neither could hope for a better future – much less suggest real strategies for improving the lives of people with tuberculosis in the nineteenth century. Beatrice Harraden’s 1893 bestseller Ships That Pass in the Night also offers a complex, bitter critique of the way in which sentimentality obscures the abuse and neglect of disabled people by nondisabled carers; it undermines the Romanticisation of consumptives, and shows consumptives driven to suicide by social marginalisation that leaves them feeling useless and hopeless. Yet its depiction of a romantic friendship between an emancipated woman and a disabled man also engages with the exciting possibilities of 1890s’ gender politics, and imagines new comradeship between disabled and nondisabled people based on mutual care and respect. Ships That Pass in the Night is a love story set in an Alpine ‘Kurhaus’ for invalids. Once enormously popular, adapted for the stage in remote corners of America and translated into several languages, including Braille, Ships was ‘said to be the only book found in the room of Cecil Rhodes when he died.’1 The novel is rarely read now, and so requires a brief synopsis. -

“Henry James and American Painting” Exhibition Explores Novelist’S Connection to Visual Art and Isabella Stewart Gardner on View: Oct

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE “Henry James and American Painting” exhibition explores novelist’s connection to visual art and Isabella Stewart Gardner On View: Oct. 19 to Jan. 21, 2018 BOSTON, MA (July 2017) – This fall, Henry James and American Painting, an exhibition that is the first to explore the relationship between James’ literary works and the visual arts, opens at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. On view from Oct. 19 to Jan. 21, 2018, it offers a fresh perspective on the master novelist and the significance of his friendships with American artists John La Farge, John Singer Sargent, and James McNeill Whistler, and close friend and esteemed arts patron, Isabella Stewart Gardner. Originating this summer at the Morgan Library and Museum, the exhibition includes a rich selection of more than 50 oil paintings, drawings, watercolors, photographs, manuscripts, letters, and printed books from 24 museums and private collections in the US, Great Britain, and Ireland. The Gardner Museum will also pay special attention to James’s enduring relationship with Gardner and their circle of mutual friends through archival objects and correspondence drawn from the Museum collection. “Isabella Stewart Gardner’s bold vision for the Museum as an artistic incubator where all disciplines of art inform and inspire each other—from visual art to dance, literature, music, and the spoken word – is as relevant as ever in today’s fluid, multi-faceted culture,” said Peggy Fogelman, the Museum’s Norma Jean Calderwood Director. "In many ways, it all began in those grand salons with Gardner, James, Sargent, and Whistler.” James, who had a distinctive, almost painterly style of writing, is best known for his books, Portrait of a Lady (1880), Washington Square (1880), The Wings of a Dove (1902), and The Ambassadors (1903). -

Henry James Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00400-9 - The Portrait of a Lady Henry James Frontmatter More information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00400-9 - The Portrait of a Lady Henry James Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00400-9 - The Portrait of a Lady Henry James Frontmatter More information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES general editors Michael Anesko, Pennsylvania State University Tamara L. Follini, University of Cambridge Philip Horne, University College London Adrian Poole, University of Cambridge advisory board Martha Banta, University of California, Los Angeles Ian F. A. Bell, Keele University Gert Buelens, Universiteit Gent Susan M. Griffin, University of Louisville Julie Rivkin, Connecticut College John Carlos Rowe, University of California, Irvine Ruth Bernard Yeazell, Yale University Greg Zacharias, Creighton University © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00400-9 - The Portrait of a Lady Henry James Frontmatter More information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES 1 Roderick Hudson 18 The Ambassadors 2 The American 19 The Golden Bowl 3 Watch and Ward 20 The Outcry 4 The Europeans 21 The Sense of the Past 5 Confidence 22 The Ivory Tower 6 Washington Square 23 A Landscape Painter and -

Modes of Female Social Existence and Adherence in Henry James's the Orp Trait of a Lady Melanie Ann Brown Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1996 Modes of female social existence and adherence in Henry James's The orP trait of a Lady Melanie Ann Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Melanie Ann, "Modes of female social existence and adherence in Henry James's The orP trait of a Lady " (1996). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7079. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modes of female social existence and adherence in Henry James's The Portrait of a Lady by Melanie Ann Brown A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Literature) Signatures have been redacted for privacy Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1996 With respect, gratitude, and much love, I dedicate this thesis to my family, all of whom supported my decision to hop a bus for a 55-hour trip from Providence to Des Moines in the middle of August in order to pursue -

Suggested Honors English Reading List

English Honors9 Reading List You may not read books more than once for credit (for summer reading, for class study, and/or for Reading Workshop). You must read three (3) books from this list. You will complete “My Reader’s Journal” for these three (3) books. Due on Monday, August 17. The following is a list of suggested reading for college-bound students. My suggestion for you is to select a book based on one or more of these three criteria: your knowledge of the author, a skimming of the book (read the cover or jacket, a bit of the beginning, and a portion somewhere in the middle.), or advice of others who have recommended the book. You may pick up most of these books at your local library or the Norwell Library Media Center. You may also purchase them at your local bookstores—it’s sometimes nice to have your own copy so that you can write in the book. Several of these books are also available as ebooks. If you have an ereader and your parents don’t mind purchasing the book, I would suggest this format. (Ebooks increase vocabulary because they allow the user to easily look up definitions in context.) I cannot promise that all the books on this list will be free of objectionable material. What is objectionable to one may not be objectionable to another. Choose wisely. FICTION Achebe, Chinua A Man of the People/Arrow of God/Things Fall Apart Adams, Douglas The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Agee, James A Death in the Family Aidinoff , Elsie V. -

Polysèmes, 22 | 2019 the Englishness of English Landscapes in the Eyes of Two American Artists: He

Polysèmes Revue d’études intertextuelles et intermédiales 22 | 2019 Landscapes/Cityscapes The Englishness of English Landscapes in the Eyes of Two American Artists: Henry James’s English Hours, Illustrated by Joseph Pennell Le caractère profondément anglais du paysage anglais : regard de deux artistes américains dans English Hours de Henry James illustré par Joseph Pennell Marie-Odile Salati Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/polysemes/5580 ISSN: 2496-4212 Publisher SAIT Electronic reference Marie-Odile Salati, « The Englishness of English Landscapes in the Eyes of Two American Artists: Henry James’s English Hours, Illustrated by Joseph Pennell », Polysèmes [Online], 22 | 2019, Online since 20 December 2019, connection on 24 December 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ polysemes/5580 This text was automatically generated on 24 December 2019. Polysèmes The Englishness of English Landscapes in the Eyes of Two American Artists: He... 1 The Englishness of English Landscapes in the Eyes of Two American Artists: Henry James’s English Hours, Illustrated by Joseph Pennell Le caractère profondément anglais du paysage anglais : regard de deux artistes américains dans English Hours de Henry James illustré par Joseph Pennell Marie-Odile Salati 1 In 1905 Henry James published English Hours, a travel book made up of sixteen essays, which for the most part had been released in magazines at a much earlier period, before or shortly after he settled permanently in Britain (1872 and 1877). In an earlier collection comprising half of them along with pieces on Italy and America, Portraits of Places, released in 1884, the text stood by itself. However, for the final edition, the novelist chose to solicit the pictorial contribution of another American-born expatriate, the “illustrator, etcher, and lithographer”1 Joseph Pennell, who lived in London from 1884 to 1917 and taught at the Slade School of Art. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47117-6 — the American Scene Henry James , Edited by Peter Collister Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47117-6 — The American Scene Henry James , Edited by Peter Collister Index More Information INDEX Abbey, Edwin Austin, 268, 291 n. 2 Augustine, St, 92 n. 15, 464 n. 40, 466 n. 43 The Quest and Achievement of the Holy Avilés, Pedro Menéndez de, 466 n. 43 Grail, 268 n. 53 Acropolis, Athens, 375 Bache, Richard, 312 n. 37 Acts of the Apostles, 159 n. 45 Bacon, Henry Adam, Robert, 285 n. 26 Franklin at Home at Philadelphia, 312 n. 38 Adams, Henry, 317 n. 47, 345 n. 1, 346 n. 3, 348 Baedeker, Karl, 467 n. 47 n. 8, 354 n. 19 Guide, 467 Adams, Marian Hooper, 346 n. 3, 353 n. 16, Baghdad, 230 354–5, nn. 18, 19 Balzac, Honoré de, 38 n. 60 Adler, Jacob, 220 n. 12 Barbizon school, 165 n. 59 Adriatic Sea, 220 Barnum, P.T., 92 n. 18 Aeschylus, 57 n. 93 Bartholdi, Frédéric Auguste Agassiz, Louis, 380 n. 7 Fountain of Light and Water, 371 n. 43 Alcott, Amos Bronson, 275 n. 5 Baudelaire, Charles, 122 n. 71 American Academy of Arts, 376 n. 1 Beaux, Cecilia, 314 n. 40 American Civil War, 72, 188, 245, 325–326, Beecher, Henry Ward, 50 n. 84 367 n. 33, 376 n. 1, 379–80, 381 n. 10, Benedict, Clara Woolson, 114 n. 57, 430 n. 39 382 n. 11, 384, 386 n. 16, 388, 391 n. 27, Benedict, Clare, 114 n. 57 393–4, 413, 422 n. 22, 428 n. 36, Benson, Frank W., 37 n. 58 467 n.