The Project Dovetails and Expands on Efforts by the Donor Community to Assist Government in the Decentralization Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 Secretary General César Gaviria

Electoral Observations in the Americas Series, No. 13 Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 Secretary General César Gaviria Assistant Secretary General Christopher R. Thomas Executive Coordinator, Unit for the Promotion of Democracy Elizabeth M. Spehar This publication is part of a series of UPD publications of the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States. The ideas, thoughts, and opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the OAS or its member states. The opinions expressed are the responsibility of the authors. OEA/Ser.D/XX SG/UPD/II.13 August 28, 1998 Original: Spanish Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 General Secretariat Organization of American States Washington, D.C. 20006 1998 Design and composition of this publication was done by the Information and Dialogue Section of the UPD, headed by Caroline Murfitt-Eller. Betty Robinson helped with the editorial review of this report and Jamel Espinoza and Esther Rodriguez with its production. Copyright @ 1998 by OAS. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced provided credit is given to the source. Table of contents Preface...................................................................................................................................vii CHAPTER I Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER II Pre-election situation .......................................................................................................... -

Quantifying Arbovirus Disease and Transmission Risk at the Municipality

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.20143248; this version posted July 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 1 Title: Quantifying arbovirus disease and transmission risk at the municipality 2 level in the Dominican Republic: the inception of Rm 3 Short title: Epidemic Metrics for Municipalities 4 Rhys Kingston1, Isobel Routledge1, Samir Bhatt1, Leigh R Bowman1* 5 1. Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Imperial College London, UK 6 *Corresponding author 7 [email protected] 8 9 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. 1 medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.20143248; this version posted July 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 2 10 Abstract 11 Arboviruses remain a significant cause of morbidity, mortality and economic cost 12 across the global human population. Epidemics of arboviral disease, such as Zika 13 and dengue, also cause significant disruption to health services at local and national 14 levels. This study examined 2014-16 Zika and dengue epidemic data at the sub- 15 national level to characterise transmission across the Dominican Republic. -

Topography and Geology Esperanza III, Which

The Study on the Integrated Rural Development of Former Sugarcane Plantation Area and Final Report the Pilot Project of La Luisa Area, Monte Plata Province 5.4 Model Area of Group C : Esperanza III Area 5.4.1 Natural Conditions (1) Topography and Geology Esperanza III, which belongs to Valverde Province in the northwest of the Dominican Republic, is located at the 12km northeast of Mao where is the seat of the provincial office and at the 33km northwest of Santiago where is the second largest city in the country. The area is at longitude 71°12’ W and latitude 18°27’ N. The farmland of the area is situated between the Yaque del Norte River and Northern Mountains and declines gently from north to south within 80m to 100m in altitude. The area mainly consists of fluvial deposits such as muck, limy sand, clay and gravel in the Quaternary by the Yaque del Norte River and its tributaries. (2) Meteorology Esperanza III is located in Cibao that is a granary of the Dominican Republic, and is 12-km far from Mao where meteorological data are collected. In Mao where is in the middle of Cibao Valley, annual rainfall records about 700-mm but Esperanza III is supposed to have more rainfall, more than 1000 mm, since the area is at the foot of Septentrional Mountains. A vegetation map shows that Esperanza III is a part of subtropical dry forest as the same as Tamayo. The meteorological data in Mao indicate that there are two rainy seasons (from May to June and from September to October) but more than six months have less than 5 rainy days. -

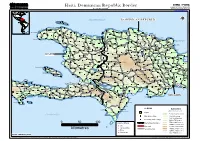

Haiti, Dominican Republic Border Geographic Information and Mapping Unit As of February 2004 Population and Geographic Data Section Email : [email protected]

GIMU / PGDS Haiti, Dominican Republic Border Geographic Information and Mapping Unit As of February 2004 Population and Geographic Data Section Email : [email protected] ATLANTIC OCEAN DOMINICANDOMINICAN REPUBLICREPUBLIC !!! Voute I Eglise ))) ))) Fond Goriose ))) ))) ))) Saint Louis du Nord ))) ))) ))) ))) Cambronal Almaçenes ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Monte Cristi ))) Jean Rabel ))) ))) Bajo Hondo ))) ))) ))) Gélin ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Sabana Cruz ))) La Cueva ))) Beau Champ ))) ))) Haiti_DominicanRepBorder_A3LC Mole-Saint-Nicolas ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Bassin ))) Barque ))) Los Icacos ))) ))) Bajo de Gran Diablo )))Puerto Plata ))) Bellevue ))) Beaumond CAPCAPCAP HAITIEN HAITIENHAITIEN ))) Palo Verde CAPCAPCAP HAITIEN )HAITIEN)HAITIEN) ))) PUERTOPUERTOPUERTO PLATA PLATAPLATA INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL ))) ))) Bambou ))) ))) Imbert ))) VVPUERTOPUERTOPUERTO))) PLATA PLATAPLATA INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL VV ))) VV ))) ))) ))) VV ))) Sosúa ))) ))) ))) Atrelle Limbé VV ))) ))) ))) ))) VV ))) ))) ))) ))) VV ))) ))) ))) Fatgunt ))) Chapereau VV Lucas Evangelista de Peña ))) Agua Larga ))) El Gallo Abajo ))) ))) ))) ))) Grande Plaine Pepillo Salcedo))) ))) Baitoa ))) ))) ))) Ballon ))) ))) ))) Cros Morne))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Sabaneta de Yásica ))) Abreu ))) ))) Ancelin ))) Béliard ))) ))) Arroyo de Leche Baie-de-Henne ))) ))) Cañucal ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) La Plateforme ))) Sources))) Chaudes ))) ))) Terrier Rouge))) Cacique Enriquillo ))) Batey Cerro Gordo ))) Aguacate del Limón ))) Jamao al Norte ))) ))) ))) Magante Terre Neuve -

2714 Surcharge Supp Eng.V.1

Worldwide Worldwide International Extended Area Delivery Surcharge ➜ Locate the destination country. ➜ Locate the Postal Code or city. ➜ If the Postal Code or city is not listed, the entry All other points will apply. ➜ A surcharge will apply only when a “Yes” is shown in the Extended Area Surcharge column. If a surcharge applies, add $30.00 per shipment or $0.30 per pound ($0.67 per kilogram), whichever is greater, to the charges for your shipment. COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED COUNTRY EXTENDED POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA POSTAL CODE AREA OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE OR CITY SURCHARGE ARGENTINA BOLIVIA (CONT.) BRAZIL (CONT.) CHILE (CONT.) COLOMBIA (CONT.) COLOMBIA (CONT.) DOMINICAN REPUBLIC (CONT.) DOMINICAN REPUBLIC (CONT.) 1891 – 1899 Yes Machacamarca Yes 29100 – 29999 Yes El Bosque No Barrancabermeja No Valledupar No Duarte Yes Monte Plata Yes 1901 – 1999 Yes Mizque Yes 32000 – 39999 Yes Estación Central No Barrancas No Villa de Leiva No Duverge Yes Nagua Yes 2001 – 4999 Yes Oruro Yes 44471 – 59999 Yes Huachipato No Barranquilla No Villavicencio No El Cacao Yes Neiba Yes 5001 – 5499 Yes Pantaleón Dalence Yes 68000 – 68999 Yes Huechuraba No Bogotá No Yopal No El Cercado Yes Neyba Yes 5501 – 9999 Yes Portachuelo Yes 70640 – 70699 Yes Independencia No Bucaramanga -

SOLO BALNEARIOS Y PLAYAS HABILES PARA EL BAÑO No

LISTADO DE PLAYAS Y BALNEARIOS HABILES PARA BAÑO SEMANA SANTA 2019 SOLO BALNEARIOS Y PLAYAS HABILES PARA EL BAÑO No. PUESTOS DE CARRETERAS / PLAYAS Y BALNEARIOS PROVINCIA REGION PERSONAL 3 BALNEARIO CACHÓN DE LA RUBIA MUNICIPIO SANTO DOMINGO ESTE OZAMA 12 7 BOMBA NATIVA, BALNEARIO PALAVE MUNICIPIO SANTO DOMINGO OESTE OZAMA 12 8 BALNEARIO PALAVE, AL FONDO MUNICIPIO SANTO DOMINGO OESTE OZAMA 12 9 BALNEARIO BIENVENIDO, EN EL PUENTE MUNICIPIO SANTO DOMINGO OESTE OZAMA 12 11 BALNEARIO RIO EL HIGÜERO MUNICIPIO SANTO DOMINGO NORTE OZAMA 12 12 BALNEARIO RIO OZAMA, EN EL PUENTE DE HACIENDA ESTRELLA MUNICIPIO SANTO DOMINGO NORTE OZAMA 12 13 BALNEARIO LAS MERCEDES, HACIENDA ESTRELLA MUNICIPIO SANTO DOMINGO NORTE OZAMA 12 14 BALNEARIO RIO GUANUMA, HACIENDA ESTRELLA MUNICIPIO SANTO DOMINGO NORTE OZAMA 12 15 BALNEARIO RIO MATA MAMON MUNICIPIO SANTO DOMINGO NORTE OZAMA 12 18 BANCO DE ARENA, BOCA CHICA MUNICIPIO BOCA CHICA OZAMA 12 19 PLAYA ANDRES - MALECON MUNICIPIO BOCA CHICA OZAMA 12 20 PLAYA DE ANDRES- MARINA ZALPAR MUNICIPIO BOCA CHICA OZAMA 12 26 BALNEARIO BOCA CHICA DULCE MUNICIPIO LOS ALCARRIZOS OZAMA 12 28 BALNEARIO LOS COROSOS, KM 25 ADENTRO MUNICIPIO PEDRO BRAND OZAMA 12 29 BALNEARIO EL LIMÓN, LA CUABA MUNICIPIO PEDRO BRAND OZAMA 12 30 BALNEARIO LA PIEDRA, LA CUABA MUNICIPIO PEDRO BRAND OZAMA 12 TOTAL 16 SANTO DOMINGO TOTAL DE PERSONAL 192 No. PUESTOS DE CARRETERAS / PLAYAS Y BALNEARIOS PROVINCIA REGION PERSONAL 35 PLAYA GUIBIA, MALECÓN DE SANTO DOMINGO DISTRITO NACIONAL OZAMA 12 TOTAL 1 DISTRITO NACIONAL TOTAL DE PERSONAL 12 No. PUESTOS DE CARRETERAS / PLAYAS Y BALNEARIOS PROVINCIA REGION PERSONAL 37 BALNEARIO LOS TUBOS, CARA LINDA, MONTE PLATA MONTE PLATA OZAMA 12 38 BALNEARIO PUENTE RIO OZAMA, D.M. -

Directorio Delegados Provinciales (Actualizado)

Directorio Delegados Provinciales Provincia/Nombres/Correo/Dirección Teléfonos AZUA Luis Alberto Díaz 809-722-2559 [email protected] 809-521-6214 C/ Duarte Esq. Vicente Noble, Azua BAHORUCO Juan de Dios Medina Florían 809-722-2560 [email protected] 809-527-9710 Ave. 27 Febrero Esq. San Bartolomé, Neyba BARAHONA Massiel Haydee De Los Santos Cueto 809-722-2561 [email protected] 809-524-7405 C/ María Montez No. 26, Esq. Jaime Mota (2do. Nivel), Barahona DAJABON Johanny Guzman 809-722-2563 [email protected] 809-579-7464 C/ Beller Esq. Victor Ml. Abreu, Dajabón DUARTE Wendy Durán Paulino 809-722-2564 [email protected] 809-725-0181 C/ 27 Febrero Esq. Restauración 3er. Piso, Edif. Gobernanción, San Francisco de Macorís ELIAS PIÑA Gloria María Alcántara Ramírez 809-722-2565 [email protected] 809-527-9605 C/ 27 Febrero frente al parque los Vagos. Edif. Gobernación, Comendador ESPAILLAT Alquides Antonio Almonte Muñóz 809-722-2567 [email protected] 809-577-6363 C/ Sánchez No. 74, 2do. Nivel Edif. Centro de Pintura Burdiez, Moca EL SEIBO Carmen E. Medina Suero 809-722-2566 [email protected] 809-552-2560 Ave. Manuela Diez frente a la Fortaleza (Solidaridad 1ra. Planta), El Seibo HATO MAYOR Fernando Betancourt Cambumba 809-722-2568 [email protected] C/Palo Hincado 3ra. Planta,oficinas Gubernamentales, Hato Mayor HERMANAS MIRABAL Martir E. Olivero De Jesús 809-722-2578 [email protected] 809-577-2055 C/ Hermanas Mirabal Esq. Maria Josefa Gomez Edif. Público, 2do. Nivel, INDEPENDENCIA Luis A. -

Taino Survival in the 21St Century Dominican Republic

Portland State University PDXScholar Black Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations Black Studies 2002 Not Everyone Who Speaks Spanish is From Spain: Taino Survival in the 21st Century Dominican Republic Pedro Ferbel-Azcarate Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/black_studies_fac Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Ferbel, P. J. (2002). "Not Everyone Who Speaks Spanish is from Spain: Taíno Survival in the 21st Century Dominican Republic". KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Black Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. KACIKE: Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology ISSN 1562-5028 Special Issue edited by Lynne Guitar NEW DIRECTIONS IN TAINO RESEARCH http://www.kacike.org/Current.html Not Everyone Who Speaks Spanish is from Spain: Taino Survival in the 21st Century Dominican Republic Dr. P. J. Ferbel Introduction that has persisted to this day. That heritage, together with the historical The national identity of the evidence for Taíno survival presented by Dominican Republic is based on an my colleagues Lynne Guitar and Jorge idealized story of three cultural roots-- Estevez, points me to the understanding Spanish, African, and Taíno--with a that the Taíno people were never extinct selective amnesia of the tragedies and but, rather, survived on the margins of struggles inherent to the processes of colonial society to the present. -

Plan Municipal De Desarrollo Azua

PLAN MUNICIPAL DE DESARROLLO AZUA Provincia Azua 2016-2020 “AZUA, CUNA PATRIÓTICA, CULTURAL Y BANANERA” Consultora: Carmen Ledesma Dirección del equipo de trabajo Arq. Marcos Martínez Ayuntamiento Municipal de Azua Asistencia Técnica: Calle Duarte # 61, Esq. Colon, Azua de Madelin Urbáez Compostela, Provincia Azua, Fiordaliza Rodríguez República Dominicana Yaniris Domínguez Tel.: 809-521-1684 Leonid Díaz [email protected] Rhina Rivera República Dominicana Dirección General de Desarrollo y Ordenamiento Territorial (DGODT). Equipo técnico Soporte: Arq. Franklin Labour Lic. Nayely Germoso Director General DGODT Todos los Derechos Reservados Dirección General de Ordenamiento Territorial 2016 INDICE ............................................................................................................................ 1 ............................................................................................................................ 1 INDICE ................................................................................................................ 1 PRESENTACIÓN ................................................................................................. 5 PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL ................................................................. 6 MARCO LEGAL DE LOS PLANES MUNICIPALES DE DESARROLLO ................ 8 PALABRAS DEL ALCALDE DE AZUA ................................................................ 11 MIEMBROS DE LA GESTIÓN MUNICIPAL ........................................................ 12 -

Dominican Republic

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Dominican Republic North Coast (p127) Península de Samaná Central (p108) Highlands (p161) Punta Cana & the Southeast (p78) #_ Santo The Southwest & Domingo Península de (p46) Pedernales (p183) THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Michael Grosberg, Kevin Raub PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to the SANTO DOMINGO . 46 Playa Limón . 104 Dominican Republic . 4 Miches . 105 Dominican Republic Map . .6 PUNTA CANA & Sabana de la Mar . 106 Dominican THE SOUTHEAST . 78 Republic’s Top 18 . .8 East of Santo PENÍNSULA Need to Know . .18 Domingo . 79 DE SAMANÁ . 108 First Time . 20 Juan Dolio . 79 Eastern Península If You Like… . 22 La Romana to Higüey . 84 de Samaná . 110 Month by Month . 25 La Romana . 84 Samaná . 110 Itineraries . 28 Bayahibe & Las Galeras . 115 Eat & Drink Dominicus Americanus . 88 Western Like a Local . 34 Higüey . 95 Península de Samaná . .119 Dominican Punta Cana to Republic Outdoors . .37 Sabana de la Mar . 96 Las Terrenas . 119 Playa Bonita . 126 Regions at a Glance . 43 Bávaro & Punta Cana . 96 MTIMOTHY O’KEEFE / GETTY IMAGES © DOMINICAN REPUBLIC MINISTRY OFTOURISM, WWW.GODOMINICANREPUBLIC.COM BEACH, PUNTA CANA P96 BRIGITTE MERLE / GETTY IMAGES © © HAITIAN MARKET, PEDERNALES P197 Contents UNDERSTAND NORTH COAST . .127 Monte Cristi . 158 Dominican Republic Today . 202 Puerto Plata . 129 Dajabón . 160 Playa Dorada History . 204 & Costa Dorada . 135 CENTRAL Music & Dance . .215 Costambar . 136 HIGHLANDS . .161 Baseball: Playa Cofresí . 137 Santiago . 162 A Dominican Passion . .218 Sosúa . 137 San José de Art & Architecture . 220 Cabarete . 143 las Matas . 169 Río San Juan . 153 La Vega . 169 Dominican Cabrera . -

Alcaldes Y Alcaldesas Periodo 2020-2024

ALCALDES Y ALCALDESAS PERIODO 2020-2024 Región Provincia Municipio Nombres Partido Distrito Nacional 1 Santo Domingo de Guzman ROSA CAROLINA MEJIA GOMEZ PRM 2 Santo Domingo Este MANUEL DE JESUS JIMENEZ ORTEGA PRM 3 Santo Domingo Norte CARLOS MARIEN ELIAS GUZMAN PLD Ozama 4 Santo Domingo Oeste JOSE DOLORES ANDUJAR RAMIREZ PRM Santo Domingo 5 Boca Chica FERMIN BRITO RINCON PLD 6 San Antonio de Guerra FRANCISCO ROJAS GARCIA PRM 7 Los Alcarrizos CRISTIAN ENCARNACION PRM 8 Pedro Brand WILSON PANIAGUA ENCARNACION PRM 9 San Juan de la Maguana HANOI Y. SÁNCHEZ PANIAGUA PLD 10 El Cercado JOSE MIGUEL MORILLO MENDEZ PLD 11 Las Matas de Farfán JOSE DE LA CRUZ GONZALEZ PLD San Juan 12 Juan de Herrera JORGE ANTONIO MERAN PLD 13 Vallejuelo SILIXTO ENCARNACIÓN CIPIÓN PLD 14 Bohechío LUIS EMILIO DE LEON PIÑA PLD El Valle 15 Comendador JULIO ALTAGRACIA NUÑEZ PEREZ PRM 16 Bánica YISSELL YAHAIRA SANTANA ALCANTARA PLD 17 Pedro Santana HIPOLITO VALENZUELA CONTRERAS PLD Elías Piña 18 Hondo Valle NILDO CÉSAR DE LOS SANTOS SOLIS PLD 19 El Llano JOSE MARIA DEL ROSARIO VALDEZ PRSC 20 Juan Santiago PASON SOLER DE OLEO PLD 21 San Cristóbal JOSE BIENVENIDO MONTAS DOMINGUEZ PRM 22 Villa Altagracia JOSE MIGUEL MENDEZ RESTITUYO PLD 23 Yaguate ROSA PEÑA GARCÍA PLD 24 Bajos de Haina OSVALDO DE JESUS RODRIGUEZ ESTEVEZ PRM San Cristóbal 25 Cambita Garabitos JOSE REMIJIO PEÑA DEL VILLAR PRM 26 San Gregorio de Nigua JORGE ORTIZ CARELA PLD 27 Sabana Grande de Palenque ANGELA DIPRE VALLEJO PLD 28 Los Cacaos MODESTO LARA ENCARNACION PRM 29 Azua RUDDY GONZALEZ PLD 30 Padre Las -

Download Vol. 21, No. 1

BULLETIN of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences Volume 21 1976 Number 1 VARIATION AND RELATIONSHIPS OF SOME HISPANIOLAN FROGS (LEPTODACTYLIDAE, ELEUTHERODACTYLUS ) OF THE RICORDI GROUP ALBERT SCHWARTZ .A-' UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM, BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, are published at irregular intervals. Volumes contain about 300 pages and are not necessarily completed in any one calendar year. CARTER R. GILBERT, Editor RHODA J. RYBAK, Managing Editor Consultant for this issue: ERNEST E. WILLIAMS Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publications and all manu- scripts should be addressed to the Managing Editor of the Bulletin, Florida State Museum, Museum Road, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611. This public document was promulgated at an annual cost of $1647.38 or $1.647 per copy. It makes available to libraries, scholars, and all interested persons the results of researchers in the natural sciences, emphasizing the Circum-Caribbean region. Publication date: Aug. 6, 1976 Price: $1.70 VARIATION AND RELATIONSHIPS OF SOME HISPANIOLAN FROGS ( LEPTODACTYLIDAE, ELEUTHERODACTYLUS) OF THE RICORDI GROUP ALBERT SCHWARTZ1 SYNOPSIS: Five species of Hispaniolan Eleutherodactylus of the ricordi group are discussed, and variation in these species is given in detail. The relationships of these five species, both among themselves and with other Antillean members of the ricordi group, are treated, and a hypothetical sequence of inter- and intra-island trends is given,