20 Questions – Respiratory Distress 20 Answers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypercapnia in Hemodialysis (HD)

ISSN: 2692-532X DOI: 10.33552/AUN.2020.01.000508 Annals of Urology & Nephrology Mini Review Copyright © All rights are reserved by David Tovbin Hypercapnia in Hemodialysis (HD) David Tovbin* Department of Nephrology, Emek Medical Center, Israel *Corresponding author: David Tovbin, Department of Nephrology, Emek Medical Received Date: February 04, 2019 Center, Afula, Israel. Published Date: February 14, 2019 Introduction 2 case reports and in our experience with similar patients, BiPAP Acute intra-dialytic exacerbation of hypercapnia in hemodialysis prevented intra-dialytic exacerbation of hypercapnia and possibly (HD) patient has been initially reported 18 years ago [1]. Subsequent respiratory arrest [1,2]. In recent years, new interest was raised similar case was reported few years later [2]. Common features of to HD dialysate bicarbonate concentration. After standardizing to both patients were morbid obesity, a previously stable HD sessions and an acute respiratory infection at time of hypercapnia [1,2]. HD pre-dialysis serum bicarbonate level was recommended as >22 patients with decreased ventilation reserve, due to morbid obesity inflammation malnutrition complex and comorbidities midweek mEq/L [11]. As higher dialysate bicarbonate concentration became with or without obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and/or obesity more prevalent, a large observation cohort study demonstrated hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) as well as chronic obstructive that high dialysate bicarbonate concentration was associated pulmonary disease (COPD), are at increased risk. COPD is common with worse outcome especially in the more acidotic patients among HD patients but frequently under-diagnosed [3]. Most [12]. However, still not enough attention is paid to HD dialysate COPD patients do well during HD with only mild- moderate pCO2 bicarbonate in the increasing number of patients with impaired increases and slightly decreased pH as compared to non-COPD ventilation, and to their risk of intra-dialytic exacerbation of chronic HD patients [2,4]. -

Basic Life Support Health Care Provider

ELLIS & ASSOCIATES Health Care Provider Basic Life Support MEETS CURRENT CPR & ECC GUIDELINES Ellis & Associates / Safety & Health HEALTH CARE PROVIDER BASIC LIFE SUPPORT - I Ellis & Associates, Inc. P.O. Box 2160, Windermere, FL 34786-2160 www.jellis.com Copyright © 2016 by Ellis & Associates, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address below. Ellis & Associates P.O. Box 2160, Windermere, FL 34786-2160 Ordering Information: Quantity sales. Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by corporations, associations, trade bookstores and wholesalers. For details, contact the publisher at the address above. Disclaimer: The procedures and protocols presented in this manual and the course are based on the most current recommendations of responsible medical sources, including the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) 2015 Guidelines for CPR & ECC. Ellis & Associates, however, make no guarantee as to, and assume no responsibility for, the correctness, sufficiency, or completeness of such recommendations or information. Additional procedures may be required under particular circumstances. Ellis & Associates disclaims all liability for damages of any kind arising from the use of, reference to, reliance on, or performance based on such information. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Not Available at Time of Printing ISBN 978-0-9961108-0-8 Unless otherwise indicated on the Credits Page, all photographs and illustrations are copyright protected by Ellis & Associates. -

Appendix A: Codes Used to Define Principal Diagnosis of COVID-19, Sepsis, Or Respiratory Disease

Appendix A: Codes used to define principal diagnosis of COVID-19, sepsis, or respiratory disease ICD-10 code Description N J21.9 'Acute bronchiolitis, unspecified' 1 J80 'Acute respiratory distress syndrome' 2 J96.01 'Acute respiratory failure with hypoxia' 15 J06.9 'Acute upper respiratory infection, unspecified' 7 U07.1 'COVID-19' 1998 J44.1 'Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with (acute) exacerbation' 1 R05 'Cough' 1 O99.52 'Diseases of the respiratory system complicating childbirth' 3 O99.512 'Diseases of the respiratory system complicating pregnancy, second trimester' 1 J45.41 'Moderate persistent asthma with (acute) exacerbation' 2 B97.29 'Other coronavirus as the cause of diseases classified elsewhere' 33 J98.8 'Other specified respiratory disorders' 16 A41.89 'Other specified sepsis' 1547 J12.89 'Other viral pneumonia' 222 J12.81 'Pneumonia due to SARS-associated coronavirus' 2 J18.9 'Pneumonia, unspecified organism' 8 R09.2 'Respiratory arrest' 1 J96.91 'Respiratory failure, unspecified with hypoxia' 1 A41.9 'Sepsis, unspecified organism' 155 R06.02 'Shortness of breath' 1 J22 'Unspecified acute lower respiratory infection' 4 J12.9 'Viral pneumonia, unspecified' 6 Appendix B: Average marginal effect by month, main analysis and sensitivity analyses Appendix C: Unadjusted mortality rate over time, by age group Appendix D: Results restricted to COVID-19, sepsis, or respiratory disease Any chronic Adjusted mortality Standardized Average marginal Age, median Male, Mortality, Month N condition, (95% Poisson limits) mortality ratio -

AC01 Page 1 of 2 Effective Jan

Contra Costa County Emergency Medical Services Cardiac Arrest History Signs and Symptoms Differential • Code status (DNR or POLST) • Unresponsive • Medical vs. trauma • Events leading to arrest • Apneic • VF vs. pulseless VT • Estimated downtime • Pulseless • Asystole • History of current illness • PEA • Past medical history • Primary cardiac event vs. respiratory arrest or drug • Medications overdose • Existence of terminal illness Decomposition AT ANY TIME Rigor mortis Criteria for death/no resuscitation Dependent lividity Yes Review DNR/POLST form Return of spontaneous circulation Injury incompatible with life or traumatic arrest with No asystole Follow FP09 ‐ Cardiac Arrest Go to Post Resuscitation TG Do not begin resuscitation Management Follow Policy 1004 – Determination of Death Begin continuous chest compressions Push hard (> 2 inches) and fast (100‐120/min) For suspected Excited Use metronome to ensure proper rate Delirium patients E Change compressors every 2 minutes (Limit changes/pulse checks to < 5 seconds) Consider fluid bolus early and Apply mechanical compression device contact Base Hospital for if available Sodium Bicarbonate order No ALS available? Yes E Apply AED if available Cardiac monitor P EtCO2 monitoring Shockable rhythm? Yes No Shockable rhythm? No Yes Continue CPR Automated defibrillation E 5 cycles over 2 minutes Follow Follow VF/VT Repeat and assess Asystole/PEA E Continue CPR and Airway TG and Airway TG 5 cycles over 2 minutes as indicated Repeat and assess as indicated Follow Airway TG Follow Airway TG Notify receiving facility. Contact Base Hospital for medical direction, as needed. Treatment Guideline AC01 Page 1 of 2 Effective Jan. 2016Effective Jan. 2020 Contra Costa County Emergency Medical Services Cardiac Arrest Pearls • Efforts should be directed at high quality and continuous chest compressions with limited interruptions. -

PALS Science Summary Table

2020 PALS Science Summary Table This table compares 2015 science with 2020 science, providing a quick reference to what has changed and what is new in the science of pediatric advanced life support. PALS topic 2015 2020 Pediatric Chain of 5 links for both chains (IHCA and OHCA Chains 6 links for both chains (IHCA and OHCA Chains Survival of Survival) of Survival); added a Recovery link to the end of both chains Pediatric • Rescue breathing: If there is a palpable • Rescue breathing: For infants and children Ventilation Rate pulse 60/min or greater but there is with a pulse but absent or inadequate inadequate breathing, give rescue breaths respiratory effort, give 1 breath every 2 to 3 at a rate of about 12 to 20/min (1 breath seconds (20-30 breaths/min). every 3-5 seconds) until spontaneous • During CPR with an advanced airway: target breathing resumes. a respiratory rate range of 1 breath every 2 • During CPR with an advanced airway: If the to 3 seconds (20-30 breaths/min), infant or child is intubated, ventilate at a accounting for age and clinical condition. rate of about 1 breath every 6 seconds Rates exceeding these recommendations (10/min) without interrupting chest may compromise hemodynamics. compressions. Cuffed Both cuffed and uncuffed ETTs are acceptable Cuffed ETTs can be used over uncuffed ETTs Endotracheal for intubating infants and children. In certain for intubating infants and children. When a Tubes circumstances (eg, poor lung compliance, high cuffed ETT is used, attention should be paid to airway resistance, or a large glottic air leak), a ETT size, position, and cuff inflation pressure cuffed ETT may be preferable to an uncuffed (usually less than 20-25 cm H2O). -

CPR/AED for Professional Rescuers and Health Care Providers HANDBOOK

CPR/AED for Professional Rescuers and Health Care Providers HANDBOOK American Red Cross CPR/AED for Professional Rescuers and Health Care Providers HANDBOOK This CPR/AED for Professional Rescuers and Health Care Providers Handbook is part of the American Red Cross CPR/AED for Professional Rescuers and Health Care Providers program. By itself, it does not constitute complete and comprehensive training. Visit redcross.org to learn more about this program. The emergency care procedures outlined in this book refl ect the standard of knowledge and accepted emergency practices in the United States at the time this book was published. It is the reader’s responsibility to stay informed of changes in emergency care procedures. PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING TERMS AND CONDITIONS BEFORE AGREEING TO ACCESS AND DOWNLOAD THE AMERICAN RED CROSS MATERIALS. BY DOWNLOADING THE MATERIALS, YOU HEREBY AGREE TO BE BOUND BY THE TERMS AND CONDITIONS. The downloadable electronic materials, including all content, graphics, images and logos, are copyrighted by and the exclusive property of The American National Red Cross (“Red Cross”). Unless otherwise indicated in writing by the Red Cross, the Red Cross grants you (“recipient”) the limited right to download, print, photocopy and use the electronic materials, subject to the following restrictions: ■ The recipient is prohibited from selling electronic versions of the materials. ■ The recipient is prohibited from revising, altering, adapting or modifying the materials. ■ The recipient is prohibited from creating any derivative works incorporating, in part or in whole, the content of the materials. ■ The recipient is prohibited from downloading the materials and putting them on their own website without Red Cross permission. -

Comparison of Preoperative and Postoperative Antioxidant Levels in Patients with Adenotonsillar Hypertrophy

Eur J Rhinol Allergy 2020; 3(2): 34-8 Original Article Comparison of Preoperative and Postoperative Antioxidant Levels in Patients with Adenotonsillar Hypertrophy Adnan Ekinci1 , Hakan Dağıstan2 , Ahmet Aksoy3 , Halil Ekinci4 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Hitit University School of Medicine, Çorum, Turkey 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Bozok University School of Medicine, Yozgat, Turkey 3Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Ömer Halisdemir University School of Medicine, Niğde, Turkey 4Department of Infectious Disease and Clinic Microbiology, Yıldırım Beyazıt University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey Abstract Objective: This study aimed to compare the serum oxidative stress levels of patients with adenotonsillar hypertrophy (ATH) with those of controls and to investigate the effects of adenotonsillectomy on the oxidative stress levels. Material and Methods: Thirty healthy children (mean age, 6 years) and 30 patients with ATH (mean age, 7 years) aged 2-12 years were included in the study. Serum total oxidant status (TOS), total antioxidant status (TAS), oxidative stress index (OSI), and paraoxonase (PON) levels were compared between the patient and control groups. The preo- perative and postoperative levels were also compared within the patient group. Results: The TOS and OSI levels were significantly higher in the patient group than in the control group (p=0.007 and p=0.027, respectively). There was no significant difference between the patient and control groups in terms of the TAS and PON levels (p=0.399 and p=0.237, respectively). The TOS and OSI levels in the patient group were significantly higher in the preoperative than in the postoperative period (p=0.005 and p=0.023, respectively), whereas there were no significant differences in the TAS and PON levels between the preoperative and postoperative period (p=0.192 and p=0.262, respectively). -

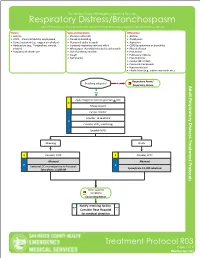

Respiratory Distress/Bronchospasm for COPD/Asthma Exacerbations and Any Bronchospasms/Wheezing Not from Pulmonary Edema

San Mateo County Emergency Medical Services Respiratory Distress/Bronchospasm For COPD/asthma exacerbations and any bronchospasms/wheezing not from pulmonary edema History Signs and Symptoms Differential • Asthma • Shortness of breath • Asthma • COPD – chronic bronchitis, emphysema • Pursed lip breathing • Anaphylaxis • Home treatment (e.g., oxygen or nebulizer) • Decreased ability to speak • Aspiration • Medications (e.g., Theophylline, steroids, • Increased respiratory rate and effort • COPD (emphysema or bronchitis) inhalers) • Wheezing or rhonchi/diminished breath sounds • Pleural effusion • Frequency of inhaler use • Use of accessory muscles • Pneumonia • Cough • Pulmonary embolus • Tachycardia • Pneumothorax • Cardiac (MI or CHF) • Pericardial tamponade • Hyperventilation • Inhaled toxin (e.g., carbon monoxide, etc.) Respiratory Arrest/ Breathing adequate? No Respiratory Failure Yes Apply Oxygen to maintain goal SpO2 > 92% E Airway support Cardiac monitor Consider, 12-Lead ECG P Consider, EtCO2 monitoring Establish IV/IO Wheezing Stridor E Consider, CPAP E Consider, CPAP Albuterol Albuterol P P Decrease LOC or unresponsive to Albuterol, Epinephrine 1:1,000 nebulized Epinephrine 1:1,000 IM Other systemic symptoms Exit to Anaphylaxis Notify receiving facility. Consider Base Hospital for medical direction Treatment Protocol R03 Page 1 of 2 Effective NovemberEffective April 2018 2020 San Mateo County Emergency Medical Services Respiratory Distress/Bronchospasm For COPD/asthma exacerbations and any bronchospasms/wheezing not from pulmonary edema Pearls • A silent chest in respiratory distress is a pre-respiratory arrest sign. • Patients receiving epinephrine should receive a 12-Lead ECG at some point in their care in the prehospital setting, but this should NOT delay the administration of Epinephrine. • Pulse oximetry monitoring is required for all respiratory patients. Treatment Protocol R03 Page 2 of 2 Effective EffectiveNovember April 2018 2020. -

Otolaryngologic Manifestations of Achondroplasia

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Otolaryngologic Manifestations of Achondroplasia William O. Collins, MD; Sukgi S. Choi, MD Objective: To describe the common otolaryngologic going tympanostomy tube insertion. Nine patients (41%) manifestations in patients with achondroplasia. had adenotonsillar hypertrophy, 6 of whom had poly- somnogram-documented obstructive sleep apnea. Seven Design: Retrospective review. patients underwent adenotonsillectomy (TA). Two pa- tients had significant residual postoperative obstructive Setting: Tertiary care children’s hospital. sleep apnea, and 1 patient died from acute respiratory distress syndrome following TA. All patients had preop- Patients: Twenty-two patients with achondroplasia, who erative neurosurgical evaluation for foramen magnum ste- were treated from 1994 to 2005, with a focus on otolar- nosis, with 11 (50%) requiring decompression. No other yngologic diagnoses. airway or laryngeal diagnoses were seen. Main Outcome Measures: Descriptive statistics of com- Conclusion: Patients with achondroplasia often pre- mon otolaryngologic diagnoses in patients with achon- sent with common diagnoses such as otitis media and ad- droplasia. enotonsillar hypertrophy, and familiarity with the con- Results: Of the 22 patients, 15 (68%) received an oto- dition and its common otolaryngologic manifestations logic diagnosis, including 6 with recurrent otitis media improves the likelihood of successful patient care. and 5 with otitis media with effusion, and 11 patients (50%) underwent an otologic procedure, with 10 under- Arch Otolaryngol -

Respiratory Emergencies

Respiratory Emergencies Emergency Medical Services Last Updated Seattle/King County Public Health November 29, 2015 401 5th Avenue, Suite 1200 Seattle, WA 98104 206.296.4863 Respiratory Emergencies Respiratory Emergencies Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 4 ANATOMY OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM ......................................................... 4 Respiratory System Anatomy ........................................................................ 4 PHYSIOLOGY OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM ..................................................... 4 Normal Aerobic Metabolism .......................................................................... 5 Metabolism Produces Carbon Dioxide ............................................................. 5 Homeostasis ............................................................................................... 5 Blood pH .................................................................................................... 6 Hypercarbia ................................................................................................ 6 Hypoxia ..................................................................................................... 6 Metabolic Problems Affect Respirations........................................................... 7 PATIENT ASSESSMENT FOR RESPIRATORY EMERGENCIES .................................. 7 Primary Assessment ................................................................................... -

First Tier Hierarchy

First Tier Hierarchy Second Tier Hierarchy ICD-10 CM code Labels Behavioral Reaction to severe stress, unspecified F43.9 Anxiety Attack / Acute Stress Reaction /Psychological Psychiatric / Behavioral Problem F99 Mental disorder, not otherwise specified Excited (Agitated) Delirium R41.0 Excited/Agitated Delirium Altered mental status R41.82 Altered Mental Status (Unknown Cause) Behavioral / psychiatric episode R45.89 Other signs/symptoms involving emotional state Suicide attempt T14.91 Suicide attempt Cardiac Second Tier Hierarchy ICD-10 CM code Labels /Circulatory Hypertension I10 HYPERtension Angina, unstable I20.0 Cardiac: Chest Pain, Cardiac / Acute Coronary Syndrome Angina I20.9 Cardiac: Chest pain, unspecified STEMI of anterior wall I21.0 Cardiac: ST elevation (STEMI) myocardial infarction of anterior wall STEMI of inferior wall I21.1 Cardiac: ST elevation (STEMI) myocardial infarction of inferior wall STEMI of other sites I21.2 Cardiac: ST elevation (STEMI) myocardial infarction of other sites Non-ST (NSTEMI) I21.4 Cardiac: Non-ST elevation (NSTEMI) Myocardial Infarction Pulmonary embolism I26 Pulmonary Emboli / PE Cardiac tamponade I31.4 Cardiac: Tamponade Cardiac Arrest I46.9 Cardiac: Cardiac Arrest Cardiac arrhythmia/dysrhythmia I49.9 Cardiac: Rhythm Disturbance (Tachy, Brady, Ectopy, Other) CHF I50.9 Cardiac: CHF (Congestive Heart Failure) Non-traumatic intracranial hemorhrage I62.9 Head Bleed Hypotension I95.9 HYPOtension Childbirth - Infant Second Tier Hierarchy ICD-10 CM code Labels Newborn (suspected to be) affected by… P01 -

Respiratory Emergencies 16

PART 9 Medicine CHAPTER Respiratory Emergencies 16 The following items provide an overview to the purpose and content of this chapter. The Standard and Competency are from the National EMS Education Standards. STANDARD • Medicine (Content Area: Respiratory) COMPETENCY • Applies fundamental knowledge to provide basic emergency care and transporta- tion based on assessment findings for an acutely ill patient. OBJECTIVES • After reading this chapter, you should be able to: 16-1. Define key terms introduced in this chapter. i. Cystic fibrosis 16-2. Explain the importance of being able to quickly rec- j. Poisonous exposures ognize and treat patients with respiratory emergencies. k. Viral respiratory infections 16-3. Describe the structure and function of the respiratory 16-9. As allowed by your scope of practice, demonstrate system, including: administering or assisting a patient with self- a. Upper airway administration of bronchodilators by metered-dose b. Lower airway inhaler and/or small-volume nebulizer. c. Gas exchange 16-10. Differentiate between short-acting beta2 agonists d. Inspiratory and expiratory centers in the medulla appropriate for prehospital use and respiratory medi- and pons cations that are not intended for emergency use. 16-4. Demonstrate the assessment of breath sounds. 16-11. Describe special considerations in the assessment and 16-5. Describe the characteristics of abnormal breath management of pediatric and geriatric patients with sounds, including: respiratory emergencies, including: a. Wheezing a. Differences in anatomy and physiology b. Rhonchi b. Causes of respiratory emergencies c. Crackles (rales) c. Differences in management 16-6. Explain the relationship between dyspnea and 16-12. Employ an assessment-based approach in order to hypoxia.