Scholarship in Action: the Case for Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allynstewart Art Resume Feb 2020

Allyn Stewart 14 Park Street Cazenovia, NY 13035 JURIED AND INVITATIONAL EXHIBITIONS OF CREATIVE WORK SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Fragments of Nature: Digital Work on Paper, Rogers Environmental Education Center, Sherburne, NY 2016 Pattern & Form, New Works on Paper, Cazenovia Public Library, Cazenovia, NY 2015 Un-Mapping the Landscape, New Works on Paper, Artspace Gallery, College of Southern Nevada, North Las Vegas, Nevada 2013 Becoming Lost, Weisman Gallery, Rogue Community College, Grants Pass, OR New Work on Paper, North Florida Community College in the Hardee Center for the Arts, Madison, FL 2012 A Landscape of Geography, solo exhibition, Adirondack Lakes Center for the Arts, Blue Mountain Lake, NY 2009 Landscape of Memory II, The Zone VI Gallery, Sinclair Community College, Dayton, OH 2008 A Landscape of Memory, the Performing Arts Center Gallery, Illinois Central College, East Peoria, IL 2001 A Gathering of Armies, Visual Studies Workshop, Rochester, NY There Will Always be War and Rumors of War, Madelon Powers Gallery, East Stroudsburg University, East Stroudsburg, PA New Works on Paper, Manlius Pebble Hill School, Manlius, NY 1998 New Works (Bosnia Series), Cazenovia Public Library, Cazenovia, NY The Act of Forgetting, The Foundation Gallery, Herkimer County Community College, Herkimer, NY SELECTED JURIED EXHIBITIONS: ARTIST BOOKS & DIGITAL WORK ON PAPER 2019 Reveal, 2019 Members Exhibition, Stone Quarry Hill Art Park, Cazenovia, NY En Route, the Centre d’Art La Rectoria, Spain, faculty exchange exhibition Priority Mail: 2019 Mail -

Spring 2007 President’S Message Evolution Not Revolution Hen This Issue Reaches You, David S

Spring 2007 President’s Message Evolution not Revolution hen this issue reaches you, David S. Marsh 4. Evaluate the organizational structure our trail will be starting to to determine its ability to manage the W shed its winter character in goal efforts. concert with all life that embraces its 5. Assign responsibility for each goal. slender threadlike intrusion. We begin to look for signs of life emerging once again, I would like to share some of the results of seemingly so slowly at first. It is a time of our efforts with you so that you will renewal. “The seasons, like the greater understand our priorities. The long-term tides, ebb and flow across the continents. goals adopted by the Board can be found Spring advances…..It sweeps ahead like a on page 3. You should expect to hear more flood of water, racing down long valleys, about our progress as it occurs. creeping up hill sides in a rising tide” When we examined the present (Edwin Way Teale). Our anticipation organizational structure of the FLTC with increases for evidence of spring, such as reference to these long term goals, it bird migration, a phenomenon we still became apparent that it did not sufficiently understand so little about and which address the importance of increasing both brings life and excitement to the forest and Presidential Pancakes membership and marketing efforts. fields. We are approaching the vernal FLTC President David Marsh preparing Similarly, the current structure did not equinox. Change is a naturally occurring breakfast for the members of the Board at recognize the importance and need for a continual process in nature. -

2021-02-12 FY2021 Grant List by Region.Xlsx

New York State Council on the Arts ‐ FY2021 New Grant Awards Region Grantee Base County Program Category Project Title Grant Amount Western New African Cultural Center of Special Arts Erie General Support General $49,500 York Buffalo, Inc. Services Western New Experimental Project Residency: Alfred University Allegany Visual Arts Workspace $15,000 York Visual Arts Western New Alleyway Theatre, Inc. Erie Theatre General Support General Operating Support $8,000 York Western New Special Arts Instruction and Art Studio of WNY, Inc. Erie Jump Start $13,000 York Services Training Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie General Support ASI General Operating Support $49,500 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie Regrants ASI SLP Decentralization $175,000 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Buffalo and Erie County Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Historical Society Western New Buffalo Arts and Technology Community‐Based BCAT Youth Arts Summer Program Erie Arts Education $10,000 York Center Inc. Learning 2021 Western New BUFFALO INNER CITY BALLET Special Arts Erie General Support SAS $20,000 York CO Services Western New BUFFALO INTERNATIONAL Electronic Media & Film Festivals and Erie Buffalo International Film Festival $12,000 York FILM FESTIVAL, INC. Film Screenings Western New Buffalo Opera Unlimited Inc Erie Music Project Support 2021 Season $15,000 York Western New Buffalo Society of Natural Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Sciences Western New Burchfield Penney Art Center Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $35,000 York Western New Camerta di Sant'Antonio Chamber Camerata Buffalo, Inc. -

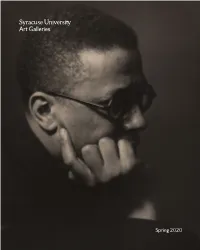

Spring 2020 Newsletter 2 Exhibitions

Spring 2020 1 Notes from the Museum March 24, 2020, is National Orange Day, marking the 150th Notes from the anniversary of the founding of Syracuse University. This important Museum milestone asks us to consider how the University shaped and impacted all the people who have been a part of it over the years and, just as importantly, how we, as part of the University today, will impact the future. As the campus art museum of Syracuse University, SUArt Galleries has an important role in this discussion because we know that art has the power to bring people together, to open our eyes to see new perspectives, and inspire us to think beyond our own experiences and disciplines. As we contemplate the future of Syracuse University, one of my goals for the museum is to bring people together, uniting the wider community with students, faculty, staff from every school and department through class visits, exhibitions and programming. With this goal, I hope the museum will be a place of rigorous interdisciplinary research, creative thinking and mindfulness, as well as an inclusive space that serves as a forum for a broad range of discussions. This spring semester brings a number of important exhibitions, Vanja Malloy, Ph.D. which I hope you’ll read about in this newsletter. Two of the shows Director and Chief Curator opening this January, Black Subjects in Modern Media Photography: Works from the George R. Rinhart Collection and Making History, Justifying Conquest: Depictions of Native Americans in American Book Company Textbooks, ask us to consider the historic role various forms of media have played in constructing and perpetuating racism. -

Contact Sheet Number159

ContaCt Sheet NUMBER159 Yolanda del amo Contact Sheet is published by LIGHT WORK a non-profit, artist-run photography organization Robert B. Menschel Media Center 316 Waverly Avenue, Syracuse, NY 13244 p: 315.443.1300 f: 315.443.9516 www.lightwork.org LIGHT WORK STAFF WE THANK Jeffrey Hoone Executive Director Robert and Joyce Menschel Hannah Frieser Director Vital Projects Fund, Inc. Mary Goodwin Associate Director JGS (Joy of Giving Something, Inc.) Mary Lee Hodgens Program Manager The New York State Council on the Arts Jessica Reed Promotions Coordinator The National Endowment for the Arts Vernon Burnett Customer Service Manager Central New York Community Foundation John Mannion Digital Lab Manager Coalition of Museum and Art Centers (CMAC) Syracuse University LIGHT WORK BOARD OF DIRECTORS and our subscribers for their support of our programs Lisa Jong-Soon Goodlin Chair Charles P. Merrihew Treasurer Kim Waale Secretary Ellen M. Blalock, Vernon Burnett, Contact Sheet is published five times a year and is available from Light Work through print Hannah Frieser, Mary Giehl, and online subscription. This is the 102nd Michael Greenlar, Jeffrey Hoone, exhibition catalogue in a series produced by Glen Lewis, Stephen Mahan, Light Work since 1985. Scott Strickland ISSN: 1064-640X ISBN: 0-935445-70-6 Contents copyright ©2010 Light Work Visual Studies, Inc., except where noted. All rights reserved. Eastwood Litho, Inc. Printer Light Work/Community Darkrooms Prepress ContaCt Sheet NUMBER159 Yolanda del amo arChipelago November 1–December 23, 2010 Reception: Thursday, November 4, 5pm LIGHT WORK Robert B. Menschel Media Center 316 Waverly Avenue Syracuse, New York 13244 Gallery hours are 10am to 6pm Sunday through Friday except for school holidays Lives lived together can grow closer or more distant Rendered in the exquisite detail made pos- constant push and pull between public and private, in the vast space opened up by silence. -

Allyn Stewart 14 Park Street Cazenovia, NY 13035 315.655.4873 [email protected]

Allyn Stewart 14 park Street Cazenovia, NY 13035 315.655.4873 [email protected] EDUCATION M. F. A. Art Media Studies, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York M. A. Museum, Editing, Archival Studies, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania B. F. A. Art History/Painting, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York AWARDS/GRANTS/FELLOWSHIPS 1998 New York Foundation for the Arts, Computer Arts Panelist, Artists’ Fellowships 1997 Light Work, Artist-in-Residency/Digital Imaging, Syracuse NY 1996 Teachers Summer Institute, Graphic Arts Education & Research Foundation, SUNY Oswego, NY 1994 National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Seminar, University of California, Berkeley, CA 1993 S.O.S. New York Foundation for the Arts Artist’s Grant 1992 Light Work Grant Recipient, Syracuse, NY 1991 Artist in Residency, Experimental Television Center, Oswego, NY 1985 Film Fund Recipient PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: TEACHING Assistant Professor, Visual Communications Program, Cazenovia College, Cazenovia, NY (2000 - Current) Courses taught: History of Graphic Design, Contemporary Developments in the Arts, Arts in the Community, Digital Illustration, Typography and Digital Bookmaking, Typography, Senior Project, Senior Seminar, Digital Design I, II, & III, and Advertising Design. Adjunct Assistant Professor, Syracuse University, School of Art and Design, Syracuse, NY (2000 - 2003) Courses taught for the Foundations Program: Time Arts, for the Department of Visual Communications: Design Methods, Design Skills and Processes. Assistant Professor, Advertising Graphic Design Department, Marywood University, Scranton, PA (1998 - 2000) Courses taught: Advertising Graphics I, Advertising Graphics II, Advanced Advertising Graphics III, Advanced Problems in Visual Communications and Typography. (Adjunct) Assistant Professor, Cazenovia College, Cazenovia, NY (1991 - 1998) Courses taught: Western Art History (I and II ), Basic Design I, History of American Film, The Creative Process, Digital Imaging, and Electronic Design I, II, and III. -

Southwest Community Center

Would you trust a craftsfair over 30 years old? 17 0 ''t4. PLOWSHARES DEC 2-3 SATURDAY 10-5PM SUNDAY NOON-5PM SOUTHWEST COMMUNITY CENTER 401 SOUTH AVENUE, SYRACUSE, NY Plowshares is a Syracuse community craftsfair celebrating a world where people enjoy their work and have control over it. It is one of the main fundraisers of the Syracuse Peace Council Published Monthly by the Syracuse Peace Council - Founded in 1936 - I55N 0735-41341 QP~te News(e(alz December 2000 PNL 697 Neer Yorke Voice for Peace and oeia: . ~etice Contents No Solution to Global Climate Change 3 Burma : Something Went Wrong 4 The Pesticide Wars Of Onondaga County 5 Teen: Animated Blood and Violence 5 Peaces 6 Plowshares Program 7 Even Bird Watching is Dangerous in Colombia 11 Calendar 15 About This Issue This issue is a kind of mixed bag with a clear focus Remembering Joan Goldberg on the Peace Council's annual Plowhares Craftsfair. Feb. 13, 1935 - Dec. 14, 1999 Included as well are articles about Light Work/Commu- nity Darkroom's photo exhibit, the continuing threat of During recent weeks the local chapter of the Jewish Peace Fellow- nuclear power and the dangers of chemical pesticide ship (JPF) has engaged in a flurry of activity . As we have met and applications . You will also see a variety of advertise- vigiled to provide a Jewish voice for a just peace in Israel and Palestine, ments for goods and services, including a two page ad we have sorely missed Joan Goldberg's presence. Joan was an active from the Syracuse Real Food Co-op . -

2017 Light Work Grants: Mary Helena Clark, Joe Librandi-Cowen, Stephanie Mercedes

Light Work 316 Waverly Ave. Syracuse, NY 13244 315.443.1300 Stephanie Mercedes, Castigos, http://www.lightwork.org 2017, Mary Helena Clark, 2017, Joe Librandi-Cowan, The Auburn System Line-up, 2015 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 10, 2017 2017 Light Work Grants: Mary Helena Clark, Joe Librandi-Cowen, Stephanie Mercedes August 28 – October 19, 2017 Light Work Hallway Gallery Reception: Wednesday, September 13, 5-6 p.m. (Syracuse, NY August 10, 2017) Light Work is pleased to announce an exhibition of works by recipients of the 43rd annual Light Work Grants in Photography. The 2017 recipients are Mary Helena Clark, Joe Librandi-Cowan, and Stephanie Mercedes. The exhibition will be on view in the Hallway Gallery at Light Work from August 28 - October 19, 2017, with an opening reception Wednesday, September 13, from 5:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. The Light Work Grants in Photography program is a part of Light Work’s ongoing effort to provide support and encouragement to Central New York artists working in photography. Established in 1975, it is one of the longest-running photography fellowship programs in the country. Each recipient receives a $3,000 award, participates in the opening fall season exhibition, and appears in Contact Sheet: The Light Work Annual. This year’s judges were Jacqueline Bates (Photography Director, California Sunday Magazine), Kottie Gaydos (Curator and Director of Operations, Detroit Center for Contemporary Photography), and Charles Guice (Director, Charles Guice Contemporary, and Co-founder, Converging Perspectives). Mary Helena -

Photography Emphasis), Kalamazoo, MI

COLLEEN WOOLPERT Interdisciplinary artist exploring alternative visions. Lives and works in Kalamazoo, MI 315.412.5890 : [email protected] : www.colleenwoolpert.com EDUCATION MFA Syracuse University, Art Photography, Syracuse, NY BA Western Michigan University, Art (photography emphasis), Kalamazoo, MI SELECTED EXHIBITIONS / SCREENINGS 2019 Muybridge in Alaska, curated by Marc Shaffer, Alaska Native Heritage Center, Anchorage, AK 2018 Hand in Hand: Photographers and Painters Alike, University of Otago, Hocken Library, Dunedin, New Zealand 2018 Destino San Antonio, curated by Anne Wallace, Briscoe Western Art Museum, San Antonio, TX 2018 Collected, California Museum of Photography, Riverside, CA 2018 Experimental Approaches: Part I, Schneider Gallery, Chicago, IL 2018 Off the Beaten Track, The Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC 2017 Kristiansund 100 år etter, Nordic Light International Festival of Photography, Kristiansund, Norway 2017 Gray Matters, curated by Paula Tognarelli, Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester, MA 2017 Seeing Sound, curated by Jon Feinstein, Humble Arts Foundation, online 2017 ArtPrize, The Ruse Escape Rooms, Grand Rapids, MI 2017 Kirk Newman Faculty Review, Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, Kalamazoo, MI 2017 Depth Cue, curated by Chris Schneberger, Perspective Gallery, Evanston, IL 2017 Open Projector Night, curated by Nick Hartman, Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts, Grand Rapids, MI 2016 What a View! Nantucket Through the Stereoscope, Nantucket Historical Association, -

April 2019 Bar Reporter

ONONDAGA COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION BAR REPORTER FEATURED ARTICLES OCBA Inspires Young Legal Minds Through The Practice Page: Obtaining Out-Of- Annual Mock Trial Competition PAGES 4-5 State Witnesses and Documents PAGE 9 April 2019 Volume 64 Number 4 Onondaga County Bar Association CNY Philanthropy Center 431 East Fayette Street, Suite 300 Syracuse, NY 13202 315-471-2667 Our Mission: To maintain the honor and dignity of the profession of law, to cultivate social discourse among its members, and to increase its significance in promoting the due administration of Justice. UPCOMING EVENTS: Law Day - May 1st CLE | Serving Those Who Served: Helping Syracuse University College of Law, Dineen Hall Vets Access VA Benefits - May 23rd CLE | Providing Legal Representation to Syracuse University College of Law Dineen Hall, Room 350 Asylum Seekers Parts One & Two - May 3rd 950 Irving Avenue, Syracuse George H. Lowe Center for Justice First Floor Education Room CLE | Financial Responsibility, Ethics and 221 South Warren Street, Syracuse Pitfalls of Running a Small Criminal Law st th Practice - May 31 CLE | Employment Law 101 - May 9 CNY Philanthropy Center, Second Floor Ballroom CNY Philanthropy Center, Second Floor Ballroom CLE | Effective Arraignment Practices for CLE | New York State Civil Practice Laws th th and Rules - June 6 Onondaga Assigned Counsel - May 10 CNY Philanthropy Center, Second Floor Ballroom SUNY Oswego Metro Center, Syracuse CLE | What Every Lawyer Needs to Know 50-Year Luncheon - June 13th About Trauma - May 17th Pascale's at Drumlins CNY Philanthropy Center, Second Floor Ballroom Visit our website for more information. BAR REPORTER | 2 President John T. -

Onondaga Community College 61

ONONDAGA COUNTY NEW YORK 2015 EXECUTIVE BUDGET Joanne M. Mahoney County Executive William P. Fisher Deputy County Executive Mary Beth Primo Ann Rooney Deputy County Executive for Physical Services Deputy County Executive for Human Services Steven P. Morgan Chief Fiscal Officer Tara Venditti Deputy Director, Budget Administration The Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to Onondaga County, New York for its Annual Budget for the fiscal year beginning January 1, 2014. In order to receive this award, a Governmental Unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as an operations guide, as a financial plan, and as a communications device. This award is valid for a period of one year only. We believe our current budget continues to conform to program requirements, and we are submitting it to GFOA to determine its eligibility for another award. ONONDAGA COUNTY LEGISLATURE J. Ryan McMahon, II** 15th District Chairman of the Legislature Brian F. May Kevin A. Holmquist 1st District 10th District John C. Dougherty Patrick M. Kilmartin* 2nd District 11th District Jim Corl David H. Knapp 3rd District 12th District Judith A. Tassone Derek T. Shepard, Jr. 4th District 13th District Kathleen A. Rapp Casey E. Jordan 5th District 14th District Michael E. Plochocki J. Ryan McMahon, II** 6th District 15th District Danny J. Liedka Monica Williams 7th District 16th District Christopher J. Ryan Linda R. Ervin* 8th District 17th District Peggy Chase 9th District * Floor Leader ** Chairman Table of Contents Section 1 - Overview Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ -

Marvin Israel (1924-1984) Was a Syracuse Native Gifts in Kind: Who Attended the School of Art at Syracuse University As a Graduate Marvin Israel Student in 1950

Syracuse University Art Galleries Fall 2019 Notes From the Gallery This new academic year marks the sesquicentennial of Syracuse Notes From the University. It offers an opportunity to look back at the way the school Gallery has brought together faculty, students and staff over the course of 150 years, facilitating an exchange of research and ideas, and just as importantly, the founding of countless friendships. It also marks the beginning of my tenure as the second inaugural director and chief curator of the SUArt Galleries. I look forward to building on the impressive work of my predecessor, Domenic Iacono, whose time here highlighted the important role of the arts in teaching and learning across disciplines at the University. I am thrilled to take the helm of this impactful institution as we explore ways for the SUArt Galleries to connect with new audiences and inspire curiosity through its compelling exhibitions, public programs, acquisitions and opportunities for student engagement. This fall brings many fantastic new exhibitions and programs. Not a Metric Matters, opening August 15, is guest curated by DJ Hellerman from the Everson Museum. This exhibition highlights the current work of College of Visual and Performing Arts faculty, while Teaching Methods: The Legacy of Art and Design Faculty, organized by curator David Prince, examines historic faculty whose work is a part of the permanent collection. An exhibition on the Photo League and its emergence as the Vanja Malloy, Ph.D. first school of photography, curated by associate director Emily Director and Chief Curator Dittman, is on view in the Photo Study Room.