Tony Awards and Broadway Show Success 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Leadership

2018 Annual Report RISEON THE LEADERSHIP NATIONAL BOARD OF TRUSTEES James A. Miller Thomas Schumacher Matt Conover, Chair Bartlett Wealth Management, Principal and Disney Theatrical Group, President Chairman Disney Parks Live Entertainment, Cincinnati, OH Vice President of Disneyland Entertainment Deborah Voigt Award-winning opera soprano Anaheim, CA Megan Tulac Phillips Hunter Bell, Vice Chair McKinsey & Company, Head of Marketing and ADVISORY BOARD Communications, Enterprise Agility Tony-nominated playwright, EdTA Board of San Francisco, CA Sarah Jane Arnegger Directors iHeart Radio Broadway, Director New York, NY John Prignano New York, NY Debbie Hill, Secretary Music Theatre International, COO and Director of Education and Development Aretta Baumgartner Community Arts Initiatives, Founder and New York, NY Center for Puppetry Arts, Education Director Executive Director Atlanta, GA Cincinnati, OH Kim Rogers Dori Berinstein Alex Birsh Concord Theatricals, Vice President, Amateur Licensing Dramatic Forces, Producer Playbill, Vice President and Chief Digital Officer New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY J. Jason Daunter Mark Drum David Redman Scott Disney Theatrical Group, Director of Theatrical Production Stage Manager Actor, Arts Advocate, EdTA Volunteer Licensing New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY Debby Gibbs Nancy Aborn Duffy ETF Legacy Circle Committee, Chair Educator, Former Broadway Licensing Abbie Van Nostrand Concord Theatricals, Vice President, Client Tupelo, MS Company Owner Relations & Community Engagement New York, NY -

Pricing Case Study | Kaetz

BUSI 760 – Pricing Case Study | Kaetz CASE STUDY Pricing for Hanson Productions Bryan Kaetz BUSI 760 | Professor Kobus | 2 MAY 2020 CONTENTS: I. Overview ................................................................................................................... 1 II. Venue 1 Analysis: Hilton ............................................................................................. 2 III. Venue 2 Analysis: Longacre .................................................................................... 3 IV. Venue 3 Analysis: St. James .................................................................................... 4 V. Recommendation for Hanson Productions .................................................................. 5 VI. References ............................................................................................................. 6 I. BUSI 760 – Pricing Case Study | Kaetz 1 I. Overview Hanson Productions is a theater production company that was founded in the mid-1950s with off-off Broadway shows. Their first major success came in the 1970s and Hanson has become a well-known Broadway and West End production company since, winning “numerous Tony awards for both musicals and plays.” (Famigletti 1) The President of Production, Joanne Shen, produced the musical “The Detroit Riots” in 2008. Considering all production, venue, capacity, royalty, and other factors into cost considerations, Shen had to make a decision on ticket prices as well as venue choice between three theater options: Hilton Theatre, Longacre Theater, -

Hamilton at the Paramount Seattle

SPECIAL EDITION • FEBRUARY 2018 ENCORE ARTS PROGRAMS • SPECIAL EDITION HAMILTON FEBRUARY 2018 FEBRUARY PROGRAMS • SPECIAL EDITION HAMILTON ARTS ENCORE HAMILTON February 6 – March 18, 2018 Cyan Magenta Yellow Black Inks Used: 1/10/18 12:56 PM 1/11/18 11:27 AM Changes Prev AS-IS Changes See OK OK with Needs INITIALS None Carole Guizetti — Joi Catlett Joi None Kristine/Ethan June Ashley Nelu Wijesinghe Nelu Vivian Che Barbara Longo Barbara Proofreader: Regulatory: CBM Lead: Prepress: Print Buyer: Copywriter: CBM: · · · · Visual Pres: Producer: Creative Mgr Promo: Designer: Creative Mgr Lobby: None None 100% A N N U A L UPC: Dieline: RD Print Scale: 1-9-2018 12:44 PM 12:44 1-9-2018 D e si gn Galle r PD y F Date: None © 2018 Starbucks Co ee Company. All rights reserved. All rights reserved. ee Company. SBX18-332343 © 2018 Starbucks Co x 11.125" 8.625" Tickets at stgpresents.org SKU #: Bleed: SBUX FTP Email 12/15/2017 STARBUCKS 23 None 100% OF TICKET SALES GOOF TOTHE THE PARTICIPATING MUSIC PROGRAMS HIGH SCHOOL BANDS — FRIDAY, MARCH 30 AT 7PM SBX18-332343 HJCJ Encore Ad Encore HJCJ blongo014900 SBX18-332343 HotJavaCoolJazz EncoreAd.indd HotJavaCoolJazz SBX18-332343 None RELEASED 1-9-2018 Hot Java Cool Jazz None None None x 10.875" 8.375" D i sk SCI File Cabinet O t h e r LIVE AT THE PARAMOUNT IMPORTANT NOTES: IMPORTANT Vendor: Part #: Trim: Job Number: Layout: Job Name: Promo: File Name: Proj Spec: Printed by: Project: RELEASE BEFORE: BALLARD | GARFIELD | MOUNTLAKE TERRACE | MOUNT SI | ROOSEVELT COMPANY Seattle, 98134 WA 2401 Utah Avenue South2401 -

Think Beyond the Literary Canon: the Potential for Young Adult Literature Within a High School Classroom

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Williams Honors College, Honors Research The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Projects College Spring 2021 Think Beyond the Literary Canon: The Potential for Young Adult Literature within a High School Classroom Megan Mayle [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Secondary Education Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Mayle, Megan, "Think Beyond the Literary Canon: The Potential for Young Adult Literature within a High School Classroom" (2021). Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects. 1232. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/1232 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE POTENTIAL FOR YA LITERATURE | 1 Think Beyond the Literary Canon: The Potential for Young Adult Literature within a High School Classroom Megan Mayle Introduction According to the Ohio Department of Education’s (2017) English Language Arts reading standards for students in grades 9 through 12, the only authors and/or speakers mentioned directly by name as an example are W.H. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

Christopher Durang

A LOOK AT SEASON SIXTY-SEVEN Colonial Players’ 2015-16 season will take our patrons on a journey from England to New York to Boston and from the late Victorian era to 21st-century America, using comedy, drama, and THE music to relate spellbinding tales of love, laughter, and, yes, even murder. Subscriptions for either five or seven shows will be on sale soon. We hope you will join us on our journey. ★ SEPTEMBER 4-26 The season opens with Sherlock’s Last Case, a ruefully comic send-up of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories about his famed English detective. This modern version is unlike anything you’ve seen about Holmes, with a jaw-dropping twist so unexpected we will ask our patrons not to reveal the secret to those who have yet to see the play. ★ OCTOBER 16-31 Side Man is a memory play told by a narrator who relates the story of his parents' relationship over four decades from the 1950s to the 1980s. It focuses on the lives of side men - musicians who made their living playing gigs with headliners on tours and in recording sessions - at a time when rock and roll was edging out jazz and big band music. Side Man won a Tony Award and was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize. Side Man contains strong language and mature themes. ★ NOVEMBER 20-DECEMBER 13 Morning's at Seven is a charming comedy set in the early 20th century and is the second in our series of classic American plays. Originally produced in 1938, it is a story of family relationships among four sisters, three husbands, and one son and his fiancée of 12 years. -

Spencer Liff Choreographer Selected Credits Contact: 818 509-0121

spencer liff choreographer selected credits contact: 818 509-0121 < TELEVISION > So You Think You Can Dance (Season 6-10) *Emmy Nominated FOX How I Met Your Mother (Season 7-9) CBS / Dir. Pam Fryman 2 Broke Girls CBS / Dir. Phill Lewis Park and Recreation NBC / Dir. Dean Holland Mike and Molly CBS / Dir. Phill Lewis Happy Land (Pilot) MTV / Dir. Lee Toland Krieger Dancing With the Stars ABC Keeping Up With the Kardashians E! The 65th Primetime Emmy Awards CBS / Dir. Louis Horvitz 67th Tony Awards Opening Number (Assistant Chor) CBS / Neil Patrick Harris 81st Academy Awards w/Hugh Jackman, Beyonce (Asst. Choreographer) *Emmy Award Best Choreography ABC /Dr. Baz Lurhman 85th Academy Awards (Asst. Choreographer) ABC /Dir. Rob Ashford < THEATRE> Hedwig and the Angry Inch Broadway/Dir. Michael Mayer Sleepless in Seattle (World Premiere) Pasadena Playhouse/Dir. Sheldon Epps Spring Awakening Deaf West/Dir. Michael Arden Oliver! The Human Race Theatre/Dir. Alan Souza Shakespeare Theatre Co/Dir. Amanda Two Gentleman of Verona: A Rock Opera Dehnert The Wedding Singer Musical Theatre West/Dir. Larry Raben Saturday Night Fever Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines Aladdin Pasadena Playhouse/ Lythgoe Productions A Snow White Christmas Magical Pictures Ent/Lythgoe Productions An Unforgettable Journey Disney Cruise Lines A Fantasy Come True Disney Cruise Lines Trevor Live (w/Neil Patrick Harris) Trevor Project Benefit/Dir. Adam Shankman Broadway by the Year 2010 Town Hall Theatre, NYC Gypsy of the Year (w/Daniel Radcliffe) BCEFA Benefit, NYC Cry-Baby (Assistant Choreo/Dance Captain) Broadway/Dir. Mark Brokaw **2008 Astaire Award Winner: Best Male Dancer, Best Choreography Equus (Assistant Movement Director/Dance Captain) Broadway/Dir. -

An Empirical Study of the Determinants of the Run-Times of Broadway Musicals

AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF THE DETERMINANTS OF THE RUN-TIMES OF BROADWAY MUSICALS A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Katie Ferguson May 2011 AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF THE DETERMINANTS OF THE RUN-TIMES OF BROADWAY MUSICALS Katie Ferguson May 2011 Mathematical Economics Abstract With an economic impact of $9.8 billion in the 2008-09 season alone, Broadway as an industry which should be economically studied. Currently there is a large gap in scholarly literature about Broadway with only three quantitative studies having been performed. This thesis aims to help fill this gap by building off of these three studies to determine which factors influence the success- measured as total days on Broadway from opening to closing night- of a Broadway musical. This thesis focuses specifically on musicals as they have been shown in all three empirical studies to have longer runs and a larger economic impact than Broadway plays. The econometric analysis finds many variables- such as a movie version of the musical being released, and winning the Tony for Best Musical- that are predictive of loner run times. Revivals are found to have substantially shorter run times than original runs and over time, musicals are lasting longer. KEYWORDS: (Broadway, Musical, Theatre, Run-time) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 Characteristics of the Film Industry..................................................... 5 Live Theatre................................................. ..................................... 7 Modern Day Broadway..................................................................................... 9 Empirical Studies................................................ ..................................... 12 18 3 THEORY 4 DATA & METHODOLOGY 32 5 RESULTS AND CONCLUSION 52 APPENDIX A 65 WORKS CONSULTED 67 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Broadway makes an enormous impact on the local economy of New York City. -

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION a Project Of

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A project of edited by Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman Remember the Women Institute, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation founded in 1997 and based in New York City, conducts and encourages research and cultural activities that contribute to including women in history. Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel is the founder and executive director. Special emphasis is on women in the context of the Holocaust and its aftermath. Through research and related activities, including this project, the stories of women—from the point of view of women—are made available to be integrated into history and collective memory. This handbook is intended to provide readers with resources for using theatre to memorialize the experiences of women during the Holocaust. Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A Project of Remember the Women Institute By Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman This resource handbook is dedicated to the women whose Holocaust-related stories are known and unknown, told and untold—to those who perished and those who survived. This edition is dedicated to the memory of Nava Semel. ©2019 Remember the Women Institute First digital edition: April 2015 Second digital edition: May 2016 Third digital edition: April 2017 Fourth digital edition: May 2019 Remember the Women Institute 11 Riverside Drive Suite 3RE New York,NY 10023 rememberwomen.org Cover design: Bonnie Greenfield Table of Contents Introduction to the Fourth Edition ............................................................................... 4 By Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel, Founder and Director, Remember the Women Institute 1. Annotated Bibliographies ....................................................................................... 15 1.1. -

New Studio on Broadway: Music Theatre and Acting

® ® 2019 CELEBRATING JIMMY NEDERLANDER James M. Nederlander or “Jimmy,” Chairman of The Nederlander Organization, was the visionary theatrical impresario who built one of the largest private live entertainment companies in the world known for producing and presenting world-class entertainment since 1912. Jimmy started working in the theatre at age 7 sweeping floors for his father, David Tobias (D.T.) Nederlander, in Detroit, Michigan. During a career that spanned over 70 years, Jimmy amassed a network of premier legitimate theatres including nine on Broadway: the Brooks Atkinson, Gershwin, Lunt-Fontanne, Marquis, Minskoff, Nederlander, Neil Simon, Richard Rodgers, and the world famous Palace; in Los Angeles: The Pantages; in London: the Adelphi, Aldwych, and Dominion; and in Chicago: the Auditorium, Broadway Playhouse, Cadillac Palace, and CIBC Theatres, and the Oriental Theatre which this year was renamed the James M. Nederlander Theatre in Jimmy’s honor. He produced over one hundred acclaimed Broadway musicals and plays including Annie, Applause, La Cage aux Folles, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Me and My Girl, Nine, Noises Off, Peter Pan, Sweet Charity, The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickelby, The Will Rogers Follies, Woman of the Year, and many more. “Generous,” “loyal” and “trusted” are just a few of the accolades his friends use to describe him. Jimmy was beloved by the industry and the recipient of many distinguished honors including an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the University of Connecticut (2014), the Exploring the Arts Foundation Award (2014), the United Nations Foundation Champion Award (2012), The Broadway League’s Schoenfeld Vision for Arts Education Award (2011), the New York Pop’s Man of the Year (2008), and the special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement (2004). -

BOOK &MUSIC by Joe Kinosian BOOK

BOOK & MUSIC by Joe Kinosian BOOK & LYRICS by Kellen Blair DIRECTED by Scott Schwartz Printer’s Ad Printer’s Ad LEARNING & EDUCATION USING THEATRE AS A CATALYST TO INSPIRE CREATIVITY “ATC’S EDUCATION DEPARTMENT HAS BEEN NOTHING SHORT OF A MIRACLE.” -Cheryl Falvo, Crossroads English Chair / Service Learning Coordinator Theatre skills help support critical thinking, decision-making, teamwork and improvisation. It can bridge the gap from imagination to reality. We inspire students to feel that anything is possible. LAST SEASON WE REACHED OVER 11,000 STUDENTS IN 80 SCHOOLS ACROSS 8 AZ COUNTIES For more information about our Learning & Education programs, visit EDUCATION.ARIZONATHEATRE.ORG IN THIS ISSUE November-December 2014 Title Page ............................................................................5 The Cast ............................................................................. 6 About the Play .......................................................................12 About Arizona Theatre Company .......................................................15 ATC Leadership .....................................................................20 The Creative Team ................................................................... 28 Staff forMurder for Two ..............................................................36 Board of Trustees ...................................................................40 Theatre Information ................................................................. 47 Corporate and Foundation Donors ....................................................49 -

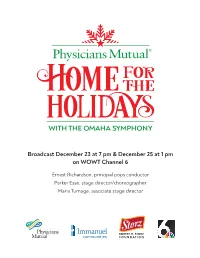

Broadcast December 23 at 7 Pm & December 25 at 1 Pm on WOWT Channel 6

Broadcast December 23 at 7 pm & December 25 at 1 pm on WOWT Channel 6 Ernest Richardson, principal pops conductor Parker Esse, stage director/choreographer Maria Turnage, associate stage director ROBERT H. STORZ FOUNDATION PROGRAM The Most Wonderful Time of the Year/ Jingle Bells JAMES LORD PIERPONT/ARR. ELLIOTT Christmas Waltz VARIOUS/ARR. KESSLER Happy Holiday - The Holiday Season IRVING BERLIN/ARR. WHITFIELD Joy to the World TRADITIONAL/ARR. RICHARDSON Mother Ginger (La mère Gigogne et Danse russe Trepak from Suite No. 1, les polichinelles) from Nutcracker PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY from Nutcracker PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY We Are the Very Model of a God Bless Us Everyone from Modern Christmas Shopping Pair A Christmas Carol from Pirates of Penzance ALAN SILVESTRI/ARR. ROSS ARTHUR SULLIVAN/LYRICS BY RICHARDSON Silent Night My Favorite Things from FRANZ GRUBER/ARR. RICHARDSON The Sound of Music RICHARD RODGERS/ARR. WHITFIELD Snow/Jingle Bells IRVING BERLIN/ARR. BARKER O Holy Night ADOLPH-CHARLES ADAM/ARR. RICHARDSON Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow JULE STYNE/ARR. SEBESKY We Need a Little Christmas JERRY HERMAN/ARR. WENDEL Frosty the Snowman WALTER ROLLINS/ARR. KATSAROS Hark All Ye Shepherds TRADITIONAL/ARR. RICHARDSON Sleigh Ride LEROY ANDERSON 2 ARTISTIC DIRECTION Ernest Richardson, principal pops conductor and resident conductor of the Omaha Symphony, is the artistic leader of the orchestra’s annual Christmas Celebration production and internationally performed “Only in Omaha” productions, and he leads the successful Symphony Pops, Symphony Rocks, and Movies Series. Since 1993, he has led in the development of the Omaha Symphony’s innovative education and community engagement programs.