Evaluation and Treatment of Chronic Pain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia in Humans Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Considerations

SPECIAL TOPIC SERIES Opioid-induced Hyperalgesia in Humans Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Considerations Larry F. Chu, MD, MS (BCHM), MS (Epidemiology),* Martin S. Angst, MD,* and David Clark, MD, PhD*w treatment of acute and cancer-related pain. However, Abstract: Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) is most broadly recent evidence suggests that opioid medications may also defined as a state of nociceptive sensitization caused by exposure be useful for the treatment of chronic noncancer pain, at to opioids. The state is characterized by a paradoxical response least in the short term.3–14 whereby a patient receiving opioids for the treatment of pain Perhaps because of this new evidence, opioid may actually become more sensitive to certain painful stimuli. medications have been increasingly prescribed by primary The type of pain experienced may or may not be different from care physicians and other patient care providers for the original underlying painful condition. Although the precise chronic painful conditions.15,16 Indeed, opioids are molecular mechanism is not yet understood, it is generally among the most common medications prescribed by thought to result from neuroplastic changes in the peripheral physicians in the United States17 and accounted for 235 and central nervous systems that lead to sensitization of million prescriptions in the year 2004.18 pronociceptive pathways. OIH seems to be a distinct, definable, One of the principal factors that differentiate the use and characteristic phenomenon that may explain loss of opioid of opioids for the treatment of pain concerns the duration efficacy in some cases. Clinicians should suspect expression of of intended use. -

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia a Qualitative Systematic Review Martin S

Anesthesiology 2006; 104:570–87 © 2006 American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Opioid-induced Hyperalgesia A Qualitative Systematic Review Martin S. Angst, M.D.,* J. David Clark, M.D., Ph.D.† Opioids are the cornerstone therapy for the treatment of an all-inclusive and current overview of a topic that may moderate to severe pain. Although common concerns regard- be difficult to grasp as a whole because new evidence ing the use of opioids include the potential for detrimental side accumulates quickly and in quite distinct research fields. effects, physical dependence, and addiction, accumulating evi- dence suggests that opioids may yet cause another problem, As such, a comprehensive review may serve as a source often referred to as opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Somewhat document. However, a systematic review also uses a paradoxically, opioid therapy aiming at alleviating pain may framework for presenting information, and such a frame- Downloaded from http://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article-pdf/104/3/570/360792/0000542-200603000-00025.pdf by guest on 01 October 2021 render patients more sensitive to pain and potentially may work may facilitate and clarify future communication by aggravate their preexisting pain. This review provides a com- clearly delineating various entities or aspects of OIH. prehensive summary of basic and clinical research concerning opioid-induced hyperalgesia, suggests a framework for organiz- Finally, a systematic review aims at defining the status ing pertinent information, delineates the status quo of our quo of our knowledge concerning OIH, a necessary task knowledge, identifies potential clinical implications, and dis- to guide future research efforts and to identify potential cusses future research directions. -

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH)

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH) Brian Johnson M.D. Assoc Prof Psychiatry and Anesthesia SUNY Upstate Medical University Disclosures • Research on shifts in the hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal system and depression during and after alcohol withdrawal sponsored by the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (Johnson 1986) Learning Objectives 1. Get the “big picture” about why opioid prescribing has accelerated recently, setting the environment for OIH to be commonplace 2. Know the definition of OIH 3. Know the neural mechanisms of OIH 4. Know the effect of methadone or buprenorphine maintenance on OIH Learning Objectives 2 5. Know how long it takes to induce OIH 6. Know what to do about OIH; with addicted patients and non-addicted patients 7. Understand the surgical pain management of a patient with OIH 1. The Big Picture • Practitioners often remark that use of opioids has become ubiquitous. The following slides show how common opioid prescribing has become, what the impetus was behind the shift in medical practice, and what are some of the unimagined consequences of a social movement that was not evidence-based. The existence of OIH has been recognized only after the impact of the right to pain treatment movement had its effect. Opioid Use Has Exploded! • 2009 USA, 5% of world’s population • 56% of global morphine • 81% of global oxycodone • 99% of global hydrocodone (Huxtable 2011) Opioid-Associated Deaths - USA • Year 1998 2005 • Oxycodone 14 1007 • Morphine 82 329 • Fentanyl 92 1245 • Methadone 8 329 (Huxtable 2011) “Pain Management: A Fundamental Human Right” “Reasons for deficiencies in pain management included cultural, societal, religious and political attitudes, including acceptance of torture. -

Diabetic Neuropathy: a Position Statement by the American

136 Diabetes Care Volume 40, January 2017 Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Rodica Pop-Busui,1 Andrew J.M. Boulton,2 Eva L. Feldman,3 Vera Bril,4 Roy Freeman,5 Statement by the American Rayaz A. Malik,6 Jay M. Sosenko,7 and Dan Ziegler8 Diabetes Association Diabetes Care 2017;40:136–154 | DOI: 10.2337/dc16-2042 Diabetic neuropathies are the most prevalent chronic complications of diabetes. This heterogeneous group of conditions affects different parts of the nervous system and presents with diverse clinical manifestations. The early recognition and appropriate man- agement of neuropathy in the patient with diabetes is important for a number of reasons: 1. Diabetic neuropathy is a diagnosis of exclusion. Nondiabetic neuropathies may be present in patients with diabetes and may be treatable by specific measures. 2. A number of treatment options exist for symptomatic diabetic neuropathy. 3. Up to 50% of diabetic peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic. If not recognized and if preventive foot care is not implemented, patients are at risk for injuries to their insensate feet. 4. Recognition and treatment of autonomic neuropathy may improve symptoms, POSITION STATEMENT reduce sequelae, and improve quality of life. Among the various forms of diabetic neuropathy, distal symmetric polyneurop- athy (DSPN) and diabetic autonomic neuropathies, particularly cardiovascular au- tonomic neuropathy (CAN), are by far the most studied (1–4). There are several 1 atypical forms of diabetic neuropathy as well (1–4). Patients with prediabetes may Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology & Diabe- – tes, Department of Internal Medicine, University also develop neuropathies that are similar to diabetic neuropathies (5 10). -

Opioid Tolerance and Hyperalgesia

Med Clin N Am 91 (2007) 199–211 Opioid Tolerance and Hyperalgesia Grace Chang, MD, MPH, Lucy Chen, MD, Jianren Mao, MD, PhD* Massachusetts General Hospital Pain Center, Division of Pain Medicine, Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA Opioids are well recognized as the analgesics of choice, in many cases, for treating severe acute and chronic pain. Exposure to opioids, however, can lead to two seemingly unrelated cellular processes, the development of opi- oid tolerance and the development of opioid-induced pain sensitivity (hyper- algesia). The converging effects of these two phenomena can significantly reduce opioid analgesic efficacy, as well as contribute to the challenges of opioid management. This article will review the definitions of opioid toler- ance (particularly to the analgesic effects) and opioid-induced hyperalgesia, examine both the animal and human study evidence of these two phenom- ena, and discuss their clinical implications. The article will also differentiate the phenomena from other aspects related to opioid therapy, including physical dependence, addiction, pseudoaddiction, and abuse. Opioid tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia Opioid tolerance is a phenomenon in which repeated exposure to an opi- oid results in decreased therapeutic effect of the drug or need for a higher dose to maintain the same effect [1]. There are several aspects of tolerance relevant to this issue [2]: Innate tolerance is the genetically determined sensitivity, or lack thereof, to an opioid that is observed during the first administration. Acquired tolerance can be divided into pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic, and learned tolerance [3]. Pharmacodynamic tolerance refers to adaptive changes that occur within systems affected by the opioid, such as opioid-induced changes in receptor density or desensitization of opioid receptors, such that response to a given * Corresponding author. -

Pharmacologic Management of Chronic Neuropathic Pain Review of the Canadian Pain Society Consensus Statement

Clinical Review Pharmacologic management of chronic neuropathic pain Review of the Canadian Pain Society consensus statement Alex Mu MD FRCPC Erica Weinberg MD Dwight E. Moulin MD PhD Hance Clarke MD PhD FRCPC Abstract Objective To provide family physicians with EDITOR’S KEY POINTS a practical clinical summary of the Canadian • Gabapentinoids and tricyclic antidepressants play an important role in Pain Society (CPS) revised consensus first-line management of neuropathic pain (NeP). Evidence published statement on the pharmacologic management since the 2007 Canadian Pain Society consensus statement on treatment of neuropathic pain. of NeP shows that serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors should now also be among the first-line agents. Quality of evidence A multidisciplinary • Tramadol and opioids are considered second-line treatments owing to their interest group within the CPS conducted a increased complexity of follow-up and monitoring, plus their potential for systematic review of the literature on the adverse side effects, medical complications, and abuse. Cannabinoids are current treatments of neuropathic pain in currently recommended as third-line agents, as sufficient-quality studies are drafting the revised consensus statement. currently lacking. Recommended fourth-line treatments include methadone, anticonvulsants with lesser evidence of efficacy (eg, lamotrigine, lacosamide), tapentadol, and botulinum toxin. There is some support for analgesic Main message Gabapentinoids, tricyclic combinations in selected NeP conditions. antidepressants, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are the first-line agents • Many of these pharmacologic treatments are off-label for pain or for treating neuropathic pain. Tramadol and on-label for specific pain conditions, and these issues should be clearly other opioids are recommended as second- conveyed and documented. -

NMDA Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain Compared to Placebo: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Open Journal of Dentistry and Oral Medicine 5(4): 59-71, 2017 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ojdom.2017.050401 NMDA Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain Compared to Placebo: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Byron Larsen1, Kristin Mau1, Mariela Padilla2, Reyes Enciso3,* 1Master of Science Program in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, USA 2Division of Periodontology, Diagnostic Sciences and Dental Hygiene, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, USA 3Division of Dental Public Health and Pediatric Dentistry, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, USA Copyright©2017 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The objective of this study is to evaluate the Neuropathic pain has been linked to structural and efficacy of N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor functional somatosensory nervous system alternations that antagonists on neuropathic pain disorders that can occur in produce spontaneous pain and pathologically intensified the orofacial region. These disorders included: Postherpetic reactions to noxious and innocuous stimuli [1]. It is Neuralgia (PHN), Complex Regional Pain Syndrome suggested that different mechanisms are at play regarding (CRPS), Atypical Odontalgia, Temporomandibular Joint orofacial neuropathic pain due to the diverse clinical (TMJ) Arthralgia and facial neuropathies. Materials and manifestations in disorders of various etiologies [2]. More Methods: Three databases (Medline through PubMed, Web specifically, involvement pertains to both peripheral and of Science, and Cochrane library) were searched on January central sensitization mechanisms [3]. -

The Journal of Rheumatology Volume 75, No. Is Fibromyalgia a Neuropathic Pain Syndrome?

The Journal of Rheumatology Volume 75, no. Is fibromyalgia a neuropathic pain syndrome? Michael C Rowbotham J Rheumatol 2005;75;38-40 http://www.jrheum.org/content/75/38 1. Sign up for TOCs and other alerts http://www.jrheum.org/alerts 2. Information on Subscriptions http://jrheum.com/faq 3. Information on permissions/orders of reprints http://jrheum.com/reprints_permissions The Journal of Rheumatology is a monthly international serial edited by Earl D. Silverman featuring research articles on clinical subjects from scientists working in rheumatology and related fields. Downloaded from www.jrheum.org on September 24, 2021 - Published by The Journal of Rheumatology Is Fibromyalgia a Neuropathic Pain Syndrome? MICHAEL C. ROWBOTHAM ABSTRACT. The fibromyalgia syndrome (FM) seems an unlikely candidate for classification as a neuropathic pain. The disorder is diagnosed based on a compatible history and the presence of multiple areas of musculoskeletal tenderness. A consistent pathology in either the peripheral or central nervous system (CNS) has not been demonstrated in patients with FM, and they are not at higher risk for diseases of the CNS such as multiple sclerosis or of the peripheral nervous system such as peripheral neuropathy. A large proportion of FM suf- ferers have accompanying symptoms and signs of uncertain etiology, such as chronic fatigue, sleep distur- bance, and bowel/bladder irritability. With the exception of migraine headaches and possibly irritable bowel syndrome, the accompanying disorders are clearly not neurological in origin. The impetus to classify the FM as a neuropathic pain comes from multiple lines of research suggesting widespread pain and tenderness are associated with chronic sensitization of the CNS. -

Neuropathic Pain (E Eisenberg, Section Editor)

Curr Pain Headache Rep (2017) 21: 28 DOI 10.1007/s11916-017-0629-5 NEUROPATHIC PAIN (E EISENBERG, SECTION EDITOR) Neuropathic Pain: Central vs. Peripheral Mechanisms Kathleen Meacham1,2 & Andrew Shepherd1,2 & Durga P. Mohapatra1,2 & Simon Haroutounian1,2 Published online: 21 April 2017 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2017 Abstract identify potentially self-sustaining infra-slow CNS oscillatory Purpose of Review Our goal is to examine the processes— activity that may be unique to pNP patients. both central and peripheral—that underlie the development of Summary While new preclinical evidence supports and ex- peripherally-induced neuropathic pain (pNP) and to highlight pands upon the key role of central mechanisms in neuropathic recent evidence for mechanisms contributing to its mainte- pain, clinical evidence for an autonomous central mechanism nance. While many pNP conditions are initiated by damage remains relatively limited. Recent findings from both preclin- to the peripheral nervous system (PNS), their persistence ap- ical and clinical studies recapitulate the critical contribution of pears to rely on maladaptive processes within the central ner- peripheral input to maintenance of neuropathic pain. Further vous system (CNS). The potential existence of an autonomous clinical investigations on the possibility of standalone central pain-generating mechanism in the CNS creates significant im- contributions to pNP may be assisted by a reconsideration of plications for the development of new neuropathic pain treat- the agreed terms or criteria for diagnosing the presence of ments; thus, work towards its resolution is crucial. Here, we central sensitization in humans. seek to identify evidence for PNS and CNS independently generating neuropathic pain signals. -

Referred Dental Pain, an Analysis of Their Prevalence and Clinical Implication

Int. J. Odontostomat., 6(2):169-173, 2012. Referred Dental Pain, an Analysis of their Prevalence and Clinical Implication Dolor Dental Referido, Análisis de su Prevalencia e Implicancias Clínicas Sônia Brandão*; Iván Suazo Galdames**; Antonio Sergio Guimarães* & Suely Nagahashi Marie*** BRANDÃO, S.; SUAZO, G. I.; GUIMARAES, A. S. & MARIE, S. N. Referred dental pain, an analysis of their prevalence and clinical implication. Int. J. Odontostomat., 6(2):169-173, 2012. SUMMARY: The study objective was to evaluate the prevalence of referred dental pain (RDP) in a group of Brazilians subjects and identify possible partnerships with sex, age and the presence of periodontal or periapical lesions. A descriptive cross-sectional study was designed, 98 patients between 14 and 64 years old (59 women and 39 men), who consulted by dental pain were evaluated clinically and radiographically in order to determine the cause and partnership with periapical and periodontal lesions and its possible territories projection other than their origin. The prevalence of RDP was 31.6%, higher in women (67.74%) though without statistical significance. The RDP was presented at a 45.16% together with periapical lesion and a 25.8% along with periodontal lesion. There was no relationship between age and RDP presence. The high prevalence of RDP found reinforces the need for a diagnosis of orofacial pain. KEY WORDS: dental pain, referred pain, periodontal lesion, periapical lesions. INTRODUCTION The pain in the oral and maxillofacial territory proper diagnosis, in addition to anamnesis, the clinician has a great impact on the quality of life (Murray et al., should use tests that include a pulp vitality test and 1996), its management requires a etiological diagno- radiographs (Ehrmann, 2002). -

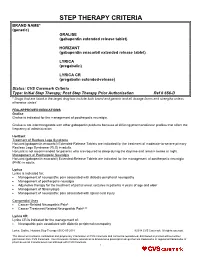

STEP THERAPY CRITERIA BRAND NAME* (Generic) GRALISE (Gabapentin Extended Release Tablet)

STEP THERAPY CRITERIA BRAND NAME* (generic) GRALISE (gabapentin extended release tablet) HORIZANT (gabapentin enacarbil extended release tablet) LYRICA (pregabalin) LYRICA CR (pregabalin extended-release) Status: CVS Caremark Criteria Type: Initial Step Therapy; Post Step Therapy Prior Authorization Ref # 656-D * Drugs that are listed in the target drug box include both brand and generic and all dosage forms and strengths unless otherwise stated FDA-APPROVED INDICATIONS Gralise Gralise is indicated for the management of postherpetic neuralgia. Gralise is not interchangeable with other gabapentin products because of differing pharmacokinetic profiles that affect the frequency of administration. Horizant Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome Horizant (gabapentin enacarbil) Extended-Release Tablets are indicated for the treatment of moderate-to-severe primary Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) in adults. Horizant is not recommended for patients who are required to sleep during the daytime and remain awake at night. Management of Postherpetic Neuralgia Horizant (gabapentin enacarbil) Extended-Release Tablets are indicated for the management of postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) in adults. Lyrica Lyrica is indicated for: Management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy Management of postherpetic neuralgia Adjunctive therapy for the treatment of partial onset seizures in patients 4 years of age and older Management of fibromyalgia Management of neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury Compendial Uses Cancer-Related Neuropathic Pain6 Cancer Treatment Related Neuropathic Pain6,12 Lyrica CR Lyrica CR is indicated for the management of: Neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy Lyrica, Gralise, Horizant Step Therapy 656-D 05-2018 ©2018 CVS Caremark. All rights reserved. This document contains confidential and proprietary information of CVS Caremark and cannot be reproduced, distributed or printed without written permission from CVS Caremark. -

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia

P A I N Tutorial 419 Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Osmond Morris1†, Larry Crowley2 1Anaesthesia Fellow, St James’s Hospital, Dublin, Ireland 2Consultant Anaesthetist, St Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland Edited by: Dr. Christopher Haley, Anaesthetic Consultant, Kingston Health Sciences, Ontario, Canada †Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] Published 3 March 2020 KEY POINTS Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) is a type of secondary hyperalgesia and results in increased sensitivity to painful stimuli in patients who have received opioids. There is significant overlap between OIH, acute opioid tolerance, and acute opioid withdrawal. These may occur in response to acute and chronic opioid exposure. The mechanism of OIH is not fully understood and is likely multifactorial; however, there is significant evidence that the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor plays a key role. A recent meta-analysis reported OIH following opioid administration, and remifentanil administration had a significant impact on patients’ postoperative pain and opioid use. Strategies to prevent and manage OIH lack evidence but centre on using a multimodal approach. INTRODUCTION Opioids have been administered for analgesic purposes for thousands of years, and as the speciality of anaesthesia has developed over the past 150 years, opioid use has remained a cornerstone of our practice. Since the Sumerians and ancient Egyptians first used opium as a cure for pain, the number of opioids available to us has increased, but so too has an understanding of their side effects. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) is one such phenomenon, and there is an increasing appreciation of its prevalence and significance. In this tutorial, we will discuss OIH, its proposed mechanism, clinical relevance to anaesthetists, and evidence on strategies to prevent and manage it in the perioperative setting.