The Problem of Fake News M R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Full Journal (PDF)

SAPIR A JOURNAL OF JEWISH CONVERSATIONS THE ISSUE ON POWER ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER RUTH CALDERON · MONA CHAREN MARK DUBOWITZ · DORE GOLD FELICIA HERMAN · BENNY MORRIS MICHAEL OREN · ANSHEL PFEFFER THANE ROSENBAUM · JONATHAN D. SARNA MEIR SOLOVEICHIK · BRET STEPHENS JEFF SWARTZ · RUTH R. WISSE Volume Two Summer 2021 And they saw the God of Israel: Under His feet there was the likeness of a pavement of sapphire, like the very sky for purity. — Exodus 24: 10 SAPIR Bret Stephens EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Mark Charendoff PUBLISHER Ariella Saperstein ASSO CIATE PUBLISHER Felicia Herman MANAGING EDITOR Katherine Messenger DESIGNER & ILLUSTRATOR Sapir, a Journal of Jewish Conversations. ISSN 2767-1712. 2021, Volume 2. Published by Maimonides Fund. Copyright ©2021 by Maimonides Fund. No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of Maimonides Fund. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. WWW.SAPIRJOURNAL.ORG WWW.MAIMONIDESFUND.ORG CONTENTS 6 Publisher’s Note | Mark Charendoff 90 MICHAEL OREN Trial and Triage in Washington 8 BRET STEPHENS The Necessity of Jewish Power 98 MONA CHAREN Between Hostile and Crazy: Jews and the Two Parties Power in Jewish Text & History 106 MARK DUBOWITZ How to Use Antisemitism Against Antisemites 20 RUTH R. WISSE The Allure of Powerlessness Power in Culture & Philanthropy 34 RUTH CALDERON King David and the Messiness of Power 116 JEFF SWARTZ Philanthropy Is Not Enough 46 RABBI MEIR Y. SOLOVEICHIK The Power of the Mob in an Unforgiving Age 124 ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER Power and Ethics in Jewish Philanthropy 56 ANSHEL PFEFFER The Use and Abuse of Jewish Power 134 JONATHAN D. -

A Dysfunctional Triangle an Analysis of America's Relations with Israel

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2015 A Dysfunctional Triangle An analysis of America’s relations with Israel and their impact on the current nuclear accord with Iran Andrew Falacci SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the American Politics Commons, International Relations Commons, Military and Veterans Studies Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Falacci, Andrew, "A Dysfunctional Triangle An analysis of America’s relations with Israel and their impact on the current nuclear accord with Iran" (2015). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2111. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2111 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Falacci A Dysfunctional Triangle An analysis of America’s relations with Israel and their impact on the current nuclear accord with Iran Andrew Falacci Geneva, Spring 2015 School of International Training -Sending School- The George Washington University, Washington D.C 1 Falacci Acknowledgements: Robert Frost talked about looking towards “the path less traveled”, where all the difference would be made. I have lived the young part of my life staying true to such advice, but I also hold dearly the realization that there are special people in my life who have, in some way or another, guided me towards that “path less traveled.” I want to take the time to thank my family for pushing me and raising me to be the person I am today. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Professional Projects from the College of Journalism Journalism and Mass Communications, College of and Mass Communications Spring 4-18-2019 Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason McCoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons McCoy, Jason, "Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media" (2019). Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects/20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln This paper will examine the development of modern media ethics and will show that this set of guidelines can and perhaps should be revised and improved to match the challenges of an economic and political system that has taken advantage of guidelines such as “objective reporting” by creating too many false equivalencies. This paper will end by providing a few reforms that can create a better media environment and keep the public better informed. As it was important for journalism to improve from partisan media to objective reporting in the past, it is important today that journalism improves its practices to address the right-wing media’s attack on journalism and avoid too many false equivalencies. -

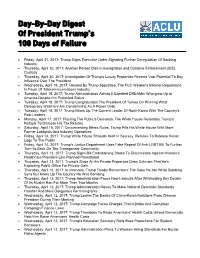

Day-By-Day Digest of President Trump's 100 Days of Failure

Day-By-Day Digest Of President Trump’s 100 Days of Failure Friday, April 21, 2017: Trump Signs Executive Order Signaling Further Deregulation Of Banking Industry Thursday, April 20, 2017: Another Person Dies In Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Custody Thursday, April 20, 2017: Investigation Of Trump's Luxury Properties Reveals Vast Potential To Buy Influence Over The President Wednesday, April 19, 2017: Headed By Trump Appointee, The FCC Weakens Internet Regulations In Favor Of Telecommunications Industry Tuesday, April 18, 2017: Trump Administration Admits It Expelled DREAMer Who grew Up In America Despite His Protected Status Tuesday, April 18, 2017: Trump Congratulates The President Of Turkey On Winning What Democracy Watchers Are Condemning As A Power Grab Tuesday, April 18, 2017: Trump Mixes Up The Current Leader Of North Korea With The Country's Past Leaders Monday, April 17, 2017: Flouting The Public's Demands, The White House Reiterates Trump's Refusal To Disclose His Tax Returns Saturday, April 15, 2017: Circumventing Ethics Rules, Trump Fills His White House With More Former Lobbyists And Industry Operatives Friday, April 14, 2017: Trump White House Shrouds Itself In Secrecy, Refuses To Release Visitor Logs To The Public Friday, April 14, 2017: Trump's Justice Department Uses Fake Repeal Of Anti-LGBT Bill To Further Turn Its Back On The Transgender Community Thursday, April 13, 2017: Trump Signs Bill Emboldening States To Discriminate Against Women's Healthcare Providers Like Planned Parenthood Thursday, -

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch Relationship in the United States

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch relationship in the United States When Donald Trump ran as a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, Rupert Murdoch was reported to be initially opposed to him, so the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post were too.1 However, Roger Ailes and Murdoch fell out because Ailes wanted to give more positive coverage to Trump on Fox News.2 Soon afterwards, however, Fox News turned more negative towards Trump.3 As Trump emerged as the inevitable winner of the race for the nomination, Murdoch’s attitude towards Trump appeared to shift, as did his US news outlets.4 Once Trump became the nominee, he and Rupert Murdoch effectively concluded an alliance of mutual benefit: Murdoch’s news outlets would help get Trump elected, and then Trump would use his powers as president in ways that supported Rupert Murdoch’s interests. An early signal of this coming together was Trump’s public attacks on the AT&T-Time Warner merger, 21st Century Fox having tried but failed to acquire Time Warner previously in 2014. Over the last year and a half, Fox News has been the major TV news supporter of Donald Trump. Its coverage has displayed extreme bias in his favour, offering fawning coverage of his actions and downplaying or rubbishing news stories damaging to him, while also leading attacks against Donald Trump’s opponent in the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton. Ofcom itself ruled that several Sean Hannity programmes in August 2016 were so biased in favour of Donald Trump and against Hillary Clinton that they breached UK impartiality rules.5 During this period, Rupert Murdoch has been CEO of Fox News, in which position he is also 1 See e.g. -

Debating the Research Agenda Around Fake News. Presented at the 2018 This Is Not a Fake Conference!, 5 June 2018, London, UK

BAXTER, G. and MARCELLA, R. 2018. Debating the research agenda around fake news. Presented at the 2018 This is not a fake conference!, 5 June 2018, London, UK. Debating the research agenda around fake news. BAXTER, G., MARCELLA, R. 2018 This document was downloaded from https://openair.rgu.ac.uk Information Search Engagement and ‘Fake News’ Debating the research agenda around ‘Fake News’ Rita Marcella and Graeme Baxter School of Creative and Cultural Business Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen ‘Post-Truth’: Oxford Dictionaries International Word of the Year 2016 First attributed to Steve Tesich in 1992, describing US Government’s involvement in Watergate, the Iran- Contra affair, and the First Gulf War Much of its use in 2016 related to the UK’s EU membership referendum (‘Brexit’) and the US presidential campaign ‘Fake news’ and ‘alternative facts’ now widely used terms (‘fake news’ was Collins Dictionary’s 2017 word of the year) Research perspectives Economics - Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives , 31(2), 211-36. Media Studies - Borden, S. L., & Tew, C. (2007). The role of journalist and the performance of journalism: Ethical lessons from “fake” news (seriously). Journal of Mass Media Ethics , 22(4), 300-314. Communications - Marchi, R. (2012). With Facebook, blogs, and fake news, teens reject journalistic “objectivity”. Journal of Communication Inquiry , 36(3), 246-262. Computer Science - Conroy, N. J., Rubin, V. L., & Chen, Y. (2015). Automatic deception detection: Methods for finding fake news. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology , 52(1), 1-4. -

Ethics Abuse in Middle East Reporting Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2009 Betraying Truth: Ethics Abuse in Middle East Reporting Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, First Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Betraying Truth: Ethics Abuse in Middle East Reporting, 1 The ourJ nal for the Study of Antisemitism (JSA) 139 (2009) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. jsa1-2_cv_jsa1-2_cv 3/1/2010 3:41 PM Page 2 Volume 1 Issue #2 Volume JOURNAL for the STUDY of ANTISEMITISM JOURNAL for the STUDY of ANTISEMITISM of the STUDY for JOURNAL Volume 1 Issue #2 2009 2009 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1564792 28003_jsa_1-2 Sheet No. 3 Side A 03/01/2010 12:09:36 \\server05\productn\J\JSA\1-2\front102.txt unknown Seq: 5 26-FEB-10 9:19 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Number 2 Preface It Never Sleeps: A Note from the Editors ......................... 89 Antisemitic Incidents around the World: July-Dec. 2009, A Partial List .................................... 93 Articles Defeat, Rage, and Jew Hatred .............. Richard L. Rubenstein 95 Betraying Truth: Ethics Abuse in Middle East Reporting .......................... -

Regulation of Lawyers in Government Beyond the Representation Role

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2019 Regulation of Lawyers in Government Beyond the Representation Role Ellen Yaroshefsky Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ellen Yaroshefsky, Regulation of Lawyers in Government Beyond the Representation Role, 33 NOTRE DAME J. L. ETHICS & PUB. POL’Y 151 (2019) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/1257 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGULATION OF LAWYERS IN GOVERNMENT BEYOND THE CLIENT REPRESENTATION ROLE ELLEN YAROSHEFSKY* INTRODUCTION In February 2017, fifteen legal ethicists filed a complaint against Kellyanne Conway, Senior Counselor to the President,' alleging that a number of her pub- lic statements were intentional misrepresentations. The complaint filed in the District of Columbia, one of the two jurisdictions where Ms. Conway is admitted to practice, acknowledged that there are limited circumstances in which lawyers who do not act in a representational capacity are, and should be, subject to the anti-deceit disciplinary rules.2 The complaint stated: As Rule 8.4(c) states, "It is professional misconduct for a lawyer to [elngage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation." This is an admittedly broad rule, as it includes conduct outside the practice of law and, unlike 8.4(b), the conduct need not be criminal. -

What's a 'Covfefe'? Trump Tweet Unites a Bewildered Nation

POLITICS What’s a ‘Covfefe’? Trump Tweet Unites a Bewildered Nation By MATT FLEGENHEIMER MAY 31, 2017 open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com An image of President Trump’s Twitter account. “Despite the constant negative press covfefe,” the post began, at 12:06 a.m. And there it ended. WASHINGTON — And on the 132nd day, just after midnight, President Trump had at last delivered the nation to something approaching unity — in bewilderment, if nothing else. The state of our union was … covfefe. The trouble began, as it so often does, on Twitter, in the early minutes of Wednesday morning. Mr. Trump had something to say. Kind of. “Despite the constant negative press covfefe,” the Twitter post began, at open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com 12:06 a.m., from @realDonaldTrump, the irrepressible internal monologue of his presidency. And that was that. A minute passed. Then another. Then five. Surely he would delete the message. Ten. Twenty. It was nearly 12:30 a.m. Forty minutes. An hour. The questions mounted. Had the president’s lawyers, so eager to curb his stream-of-consciousness missives, tackled the commander in chief under the cover of night? Perhaps, some worried aloud, Mr. Trump had experienced a medical episode a quarter of the way through his 140 characters. Or maybe he had simply gazed upon his work, paused and thought: “Yes. Nailed it.” No one at the White House could immediately be reached for comment open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com overnight. -

Learn to Discern #News

#jobs #fakenews #economy #budget #budget #election #news #news #voting #protest #law #jobs #election #news #war #protest #immigration #budget #war #candidate #voting #reform #economy #war #investigation Learn to Discern #voting #war #politics #fakenews #news #protest #jobs Media Literacy: #law Trainers Manual #election #war IREX 1275 K Street, NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20005 © 2020 IREX. All rights reserved. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Table of contents How-To Guide 4 Part B. Checking Your Emotions 83 Lesson 1: Checking your emotions 83 Principles 4 Lesson 2: Understanding headlines 86 Learn to Discern training principles 4 Lesson 3: Check Your Phone 89 General training principles 5 Part C. Stereotypes 90 Adult learner principles 6 Lesson 1: Stereotypes 90 Choosing lessons 7 Lesson 2: Stereotypes and biased reporting in the media 94 Preparation 8 Gather supplies and create handouts 8 Unit 3: Fighting Misinformation Part A: Evaluating written content: Checking sources, Unit 1: Understanding Media 99 citations, and evidence Part A: Media Landscape 11 Lesson 1: Overview: your trust gauge 99 Lesson 1: Introduction 11 Lesson 2: Go to the source 101 Lesson 2: Types of Content 19 Lesson 3: Verifying Sources and Citations 104 Lesson 3: Information vs. persuasion 24 Lesson 4: Verifying Evidence -

Exploring the Ideological Nature of Journalists' Social

Exploring the Ideological Nature of Journalists’ Social Networks on Twitter and Associations with News Story Content John Wihbey Thalita Dias Coleman School of Journalism Network Science Institute Northeastern University Northeastern University 177 Huntington Ave. 177 Huntington Ave. Boston, MA Boston, MA [email protected] [email protected] Kenneth Joseph David Lazer Network Science Institute Network Science Institute Northeastern University Northeastern University 177 Huntington Ave. 177 Huntington Ave. Boston, MA Boston, MA [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION The present work proposes the use of social media as a tool for Discussions of news media bias have dominated public and elite better understanding the relationship between a journalists’ social discourse in recent years, but analyses of various forms of journalis- network and the content they produce. Specifically, we ask: what tic bias and subjectivity—whether through framing, agenda-setting, is the relationship between the ideological leaning of a journalist’s or false balance, or stereotyping, sensationalism, and the exclusion social network on Twitter and the news content he or she produces? of marginalized communities—have been conducted by communi- Using a novel dataset linking over 500,000 news articles produced cations and media scholars for generations [24]. In both research by 1,000 journalists at 25 different news outlets, we show a modest and popular discourse, an increasing area of focus has been ideo- correlation between the ideologies of who a journalist follows on logical bias, and how partisan-tinged media may help explain other Twitter and the content he or she produces.