The Ethics Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Officials Say Flynn Discussed Sanctions

Officials say Flynn discussed sanctions The Washington Post February 10, 2017 Friday, Met 2 Edition Copyright 2017 The Washington Post All Rights Reserved Distribution: Every Zone Section: A-SECTION; Pg. A08 Length: 1971 words Byline: Greg Miller;Adam Entous;Ellen Nakashima Body Talks with Russia envoy said to have occurred before Trump took office National security adviser Michael Flynn privately discussed U.S. sanctions against Russia with that country's ambassador to the United States during the month before President Trump took office, contrary to public assertions by Trump officials, current and former U.S. officials said. Flynn's communications with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak were interpreted by some senior U.S. officials as an inappropriate and potentially illegal signal to the Kremlin that it could expect a reprieve from sanctions that were being imposed by the Obama administration in late December to punish Russia for its alleged interference in the 2016 election. Flynn on Wednesday denied that he had discussed sanctions with Kislyak. Asked in an interview whether he had ever done so, he twice said, "No." On Thursday, Flynn, through his spokesman, backed away from the denial. The spokesman said Flynn "indicated that while he had no recollection of discussing sanctions, he couldn't be certain that the topic never came up." Officials said this week that the FBI is continuing to examine Flynn's communications with Kislyak. Several officials emphasized that while sanctions were discussed, they did not see evidence that Flynn had an intent to convey an explicit promise to take action after the inauguration. Flynn's contacts with the ambassador attracted attention within the Obama administration because of the timing. -

USA Today Snapshots

USA TODAY — E1 SECTION B IN MONEY IN NEWS 03.19.17 How Trump may ROCK ’N’ ROLL FOUNDER hurt dairy farms CHUCK BERRY DIES AT 90 ROBYN BECK, AFP/GETTY IMAGES TANNEN MAURY EPA Meals on Wheels buzz has a flaw Trump Gregory Korte @gregorykorte budget’s USA TODAY impact on iconic WASHINGTON President program Trump’s first budget proposal to Congress last week specifi- to help cally identified steep cuts to seniors is hundreds of domestic pro- grams, but Meals on Wheels far from wasn’t one of them. certain The popular program — which mainly uses volunteer because drivers to provide hot meals to it doesn’t older Americans across the country — doesn’t directly re- get direct COUSIN: ‘KELLYANNE ceive federal funding. As federal Trump’s budget director, Mick Mulvaney, told reporters funding Thursday: “Meals on Wheels is WASN’T AFRAID not a federal program.” OF ANYTHING OR ANYONE’ ANNE-MARIE CARUSO, THE (BERGEN COUNTY, N.J.) RECORD Kellyanne Key Trump aide, defender Conway Conway, at TODD A. BUCHANAN, SPECIAL TO USA TODAY This is an edition of USA TODAY her home in Nevertheless, Meals on Jack Zimmer provided for . An expanded version doesn’t care when critics lash out of USA TODAY is available at Alpine, N.J., Wheels quickly became the delivers a newsstands or by subscription, and Conway has emerged as one of spends poster child for the impact of meal to Mar- at usatoday.com. Mike Kelly Trump’s most trusted advisers weekdays in Trump’s cuts. Even before the tha Scott in The (Bergen County, N.J.) Record and also why she continues to Washing- budget’s release, Rep. -

President Trump's Remarks

KEY FINDINGS 1. President Trump used the power of his office to pressure and induce the newly-elected president of Ukraine to interfere in the 2020 presidential election for President Trump’s personal and political benefit. KEY FINDINGS 2. In order to increase the pressure on Ukraine to announce the politically- motivated investigations that President Trump wanted, he withheld a coveted Oval Office meeting and $391 million of essential military assistance from Ukraine. KEY FINDINGS 3. President Trump’s conduct sought to undermine our free and fair elections and posed an imminent threat to our national security. KEY FINDINGS 4. Faced with the revelation of his pressure campaign against Ukraine, President Trump directed an unprecedented effort to obstruct Congress’ impeachment inquiry into his conduct. JULY 25, 2019 8:36 AM Good lunch - thanks. Heard from White House - assuming President Z convinces trump he will investigate / “get to the bottom of VOLKER what happened” in 2016, we will nail down date for visit to Washington. Good luck! See you tomorrow - kurt YERMAK TESTIMONY OF AMBASSADOR SONDLAND ON “QUID PRO QUO” TESTIMONY OF AMBASSADOR SONDLAND “QUID PRO QUO” “I know that members of this committee frequently frame these complicated issues in the form of a simple question: ‘Was there a quid pro quo?’ As I testified previously with regard to the requested White House call and the White House meeting, the answer is ‘yes.’ “ Transcript page 26, Open Hearing with Gordon Sondland, Nov 20, 2019. JULY 25, 2019 TRUMP-ZELENSKY CALL RECORD ZELENSKY: “I would also like to thank you for your great support in the area of defense. -

The Advocate, September 24, 1984

George Washington University Law School Scholarly Commons The Advocate, 1984 The Advocate, 1980s 9-24-1984 The Advocate, September 24, 1984 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/the_advocate_1984 Recommended Citation George Washington University Law School, 15 The Advocate 1 (1984) This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Advocate, 1980s at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Advocate, 1984 by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - "<,:. ..:: ,. The"'GW' . ':~.~\ ".";; -. ,'"; , -' a NI.C G~tSf ••• ,;~.,">"$7 Million -..;......-;...-----~--:.....---~,_~. positions at theNLC. byJackF.'. Williams Mr. Alverson's wife, the late Freda N. In a speech': recently presented by NLC Alverson, has also left a bequest of nearly Dean Jerome' A. Barron' at the annual $700,000to establish a Freda N. Alverson faculty-alumni luncheon . held at the Chair. in '..an unidentified legal field. National. Lawyers Club, Dean Barron . Another contribution in excess of $700,000 outlinedplans for expansion of the faculty by the late Theodore Rinehart will go at the NLC.The·· plans include the en- toward endowment of the Rinehart Chair dowment of' several chairs. These en-' in Business Law. In addition within a few dowments were made possible largely by. years, the Edward F. Howry Chair of trial contributions" from alumni across the advocacy will be fully endowed. ~ country. -he endowment of these chairs is Ii Among these ••coritributionS was': the ·•••··.rnuch . needed addition •to the NLC. .largestsitlgltrgift~istory:-of;the':NLG~:,,-,z""Presently,..tbe'«)nly ..-endowed.ehaiiat'the",!,"c~' and GWU. -

The Viability of Multi-Party Litigation As a Tool for Social Engineering Six Decades After the Restrictive Covenant Cases

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2011 The iV ability of Multi-Party Litigation as a Tool for Social Engineering Six Decades after the Restrictive Covenant Cases José F. Anderson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation The iV ability of Multi-Party Litigation as a Tool for Social Engineering Six Decades after the Restrictive Covenant Cases, 42 McGeorge L. Rev. 765 (2011) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Viability of Multi-Party Litigation as a Tool for Social Engineering Six Decades After the Restrictive Covenant Cases Jose Felipe Anderson ISSUE 4 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1945914 The Viability of Multi-Party Litigation as a Tool for Social Engineering Six Decades After the Restrictive Covenant Cases Jos6 Felip6 Anderson* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................... ..... 766 H. THE McGHEE V. SIPES BRIEF ................................... 774 A. McGhee Argument Against Judicial Enforcement of Restrictive Covenants .............................................. 776 B. History of Restrictive Covenants ............................. 777 C. Policy Arguments ......................................... 782 D. Deference to the UN Charter .......................................786 III. THE SHELLEY V. KRAEMER DECISION .............................. 787 IV. ANALYSIS .................................................. 789 V. -

Rinehart Right: Turnbull Must Learn from Trump

Rinehart right: Turnbull must learn from Trump Andrew Bolt, Herald Sun November 23, 2016 3:22am No minister of this Turnbull Government has welcomed the election of Donald Trump. But Gina Rinehart, the iron ore and cattle baroness, is surely right to say Trump has plenty to teach the Government - and it must follow him to save us from turning into another Greece. Mining magnate Gina Rinehart has urged the Australian government to adopt the stimulatory policies being promised by US president-elect Donald Trump or risk following Greece along an - “irresponsible’’ path of increasing government expenditure and debt. The nation’s richest woman, who recently visited Washington where she met members of Mr Trump’s campaign team — including former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani and campaign manager Kellyanne Conway — said the Republican Party team won the election “because they listened to the people of America’’. Mrs Rinehart also took a swipe at the US media, noting the Trump team prevailed in the polls despite “constant and unrelenting negative coverage of the president-elect, including at times his loyal supporters, such as his wife, in attempts to upset the focus of the president-elect’’. “People close to the president-elect and his campaign advised that their countrymen told them they wanted, firstly, less government tape, secondly less taxation, and for the USA to grow and be economically strong again, and provide more sustainable jobs. And how exciting, this is exactly what the president-elect, and his team, are advising they want to deliver for America and its struggling economy,’’ Mrs Rinehart said in a speech delivered for yesterday’s National Mining and Related Industries Day.. -

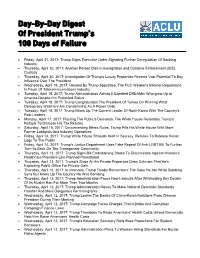

Day-By-Day Digest of President Trump's 100 Days of Failure

Day-By-Day Digest Of President Trump’s 100 Days of Failure Friday, April 21, 2017: Trump Signs Executive Order Signaling Further Deregulation Of Banking Industry Thursday, April 20, 2017: Another Person Dies In Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Custody Thursday, April 20, 2017: Investigation Of Trump's Luxury Properties Reveals Vast Potential To Buy Influence Over The President Wednesday, April 19, 2017: Headed By Trump Appointee, The FCC Weakens Internet Regulations In Favor Of Telecommunications Industry Tuesday, April 18, 2017: Trump Administration Admits It Expelled DREAMer Who grew Up In America Despite His Protected Status Tuesday, April 18, 2017: Trump Congratulates The President Of Turkey On Winning What Democracy Watchers Are Condemning As A Power Grab Tuesday, April 18, 2017: Trump Mixes Up The Current Leader Of North Korea With The Country's Past Leaders Monday, April 17, 2017: Flouting The Public's Demands, The White House Reiterates Trump's Refusal To Disclose His Tax Returns Saturday, April 15, 2017: Circumventing Ethics Rules, Trump Fills His White House With More Former Lobbyists And Industry Operatives Friday, April 14, 2017: Trump White House Shrouds Itself In Secrecy, Refuses To Release Visitor Logs To The Public Friday, April 14, 2017: Trump's Justice Department Uses Fake Repeal Of Anti-LGBT Bill To Further Turn Its Back On The Transgender Community Thursday, April 13, 2017: Trump Signs Bill Emboldening States To Discriminate Against Women's Healthcare Providers Like Planned Parenthood Thursday, -

Six Questions for Jane Mayer, Author of the Dark Side

Six Questions for Jane Mayer, Author of The Dark Side By Scott Horton, HARPER’S, July, 2008 In a series of gripping articles, Jane Mayer has chronicled the Bush Administration’s grim and furtive dealings with torture and has exposed both the individuals within the administration who “made it happen” (a group that starts with Vice President Cheney and his chief of staff, David Addington), the team of psychologists who put together the palette of techniques, and the Fox television program “24,” which was developed to help sell it to the American public. In a new book, The Dark Side, Mayer puts together the major conclusions from her articles and fills in a number of important gaps. Most significantly, we learn the details on the torture techniques and the drama behind the fierce and lingering struggle within the administration over torture, and we learn that many within the administration recognized the potential criminal accountability they faced over these torture tactics and moved frantically to protect themselves from possible future prosecution. I put six questions to Jane Mayer on the subject of her book, The Dark Side. 1. Reports have circulated for some time that the Red Cross examination of the CIA’s highly coercive interrogation regime—what President Bush likes to call “The Program”—concluded that it was “tantamount to torture.” But you write that the Red Cross categorically described the program as “torture.” The Red Cross is notoriously tight-lipped about its reports, and you do not cite your source or even note that you examined the report. Do you believe that the threat of criminal prosecution drove the Bush Administration’s crafting of the Military Commissions Act? Whether anyone involved in the Bush Administration’s interrogation and detention program will be prosecuted is as much a political question as a legal one. -

A Public Accountability Defense for National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers

A Public Accountability Defense For National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Yochai Benkler, A Public Accountability Defense For National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers, 8 Harv. L. & Pol'y Rev. 281 (2014). Published Version http://www3.law.harvard.edu/journals/hlpr/files/2014/08/ HLP203.pdf Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12786017 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP A Public Accountability Defense for National Security Leakers and Whistleblowers Yochai Benkler* In June 2013 Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras, and Barton Gellman be- gan to publish stories in The Guardian and The Washington Post based on arguably the most significant national security leak in American history.1 By leaking a large cache of classified documents to these reporters, Edward Snowden launched the most extensive public reassessment of surveillance practices by the American security establishment since the mid-1970s.2 Within six months, nineteen bills had been introduced in Congress to sub- stantially reform the National Security Agency’s (“NSA”) bulk collection program and its oversight process;3 a federal judge had held that one of the major disclosed programs violated the -

Debating the Research Agenda Around Fake News. Presented at the 2018 This Is Not a Fake Conference!, 5 June 2018, London, UK

BAXTER, G. and MARCELLA, R. 2018. Debating the research agenda around fake news. Presented at the 2018 This is not a fake conference!, 5 June 2018, London, UK. Debating the research agenda around fake news. BAXTER, G., MARCELLA, R. 2018 This document was downloaded from https://openair.rgu.ac.uk Information Search Engagement and ‘Fake News’ Debating the research agenda around ‘Fake News’ Rita Marcella and Graeme Baxter School of Creative and Cultural Business Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen ‘Post-Truth’: Oxford Dictionaries International Word of the Year 2016 First attributed to Steve Tesich in 1992, describing US Government’s involvement in Watergate, the Iran- Contra affair, and the First Gulf War Much of its use in 2016 related to the UK’s EU membership referendum (‘Brexit’) and the US presidential campaign ‘Fake news’ and ‘alternative facts’ now widely used terms (‘fake news’ was Collins Dictionary’s 2017 word of the year) Research perspectives Economics - Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives , 31(2), 211-36. Media Studies - Borden, S. L., & Tew, C. (2007). The role of journalist and the performance of journalism: Ethical lessons from “fake” news (seriously). Journal of Mass Media Ethics , 22(4), 300-314. Communications - Marchi, R. (2012). With Facebook, blogs, and fake news, teens reject journalistic “objectivity”. Journal of Communication Inquiry , 36(3), 246-262. Computer Science - Conroy, N. J., Rubin, V. L., & Chen, Y. (2015). Automatic deception detection: Methods for finding fake news. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology , 52(1), 1-4. -

Some Doubts Concerning the Proposal to Elect the President by Direct Popular Vote

Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 4 1968 Some Doubts Concerning the Proposal to Elect the President by Direct Popular Vote Albert J. Rosenthal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Election Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Legislation Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Albert J. Rosenthal, Some Doubts Concerning the Proposal to Elect the President by Direct Popular Vote, 14 Vill. L. Rev. 87 (1968). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol14/iss1/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Rosenthal: Some Doubts Concerning the Proposal to Elect the President by Dir FALL 1968] THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE SOME DOUBTS CONCERNING THE PROPOSAL TO ELECT THE PRESIDENT BY DIRECT POPULAR VOTE ALBERT J. ROSENTHALt WrITH THE GROWING INTEREST IN, and support for, pro- posals to change the method of electing the President of the United States,1 the recent Symposium on the subject in the Villanova. Law Review2 is particularly timely. Equally welcome is the invitation for additional commentary on the subject. The faults in the existing method of choosing our Presidents are well known. The current drive to replace it with direct nationwide popular election has obvious appeal - so obvious in fact that it has garnered much uncritical support. -

Corporate and Foreign Interests Behind White House Push to Transfer U.S

Corporate and Foreign Interests Behind White House Push to Transfer U.S. Nuclear Technology to Saudi Arabia Prepared for Chairman Elijah E. Cummings Second Interim Staff Report Committee on Oversight and Reform U.S. House of Representatives July 2019 oversight.house.gov EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On February 19, 2019, the Committee on Oversight and Reform issued an interim staff report prepared for Chairman Elijah E. Cummings after multiple whistleblowers came forward to warn about efforts inside the White House to rush the transfer of U.S. nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia. As explained in the first interim staff report, under Section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act, the United States may not transfer nuclear technology to a foreign country without the approval of Congress in order to ensure that the agreement meets nine nonproliferation requirements to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. These agreements, commonly known as “123 Agreements,” are typically negotiated with career experts at the National Security Council (NSC) and the Departments of State, Defense, and Energy. The “Gold Standard” for 123 Agreements is a commitment by the foreign country not to enrich or re-process nuclear fuel and not to engage in activities linked to the risk of nuclear proliferation. During the Obama Administration, Saudi Arabia refused to agree to the Gold Standard. During the Trump Administration, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) went further, proclaiming: “Without a doubt, if Iran developed a nuclear bomb, we will follow suit as soon as possible.” There is strong bipartisan opposition to abandoning the “Gold Standard” for Saudi Arabia in any future 123 Agreement.