Comic Authorship Itself Becomes All the More Pressing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Watchmen" After 9/11

Swarthmore College Works Film & Media Studies Faculty Works Film & Media Studies Fall 2011 Adapting "Watchmen" After 9/11 Bob Rehak Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bob Rehak. (2011). "Adapting "Watchmen" After 9/11". Cinema Journal. Volume 51, Issue 1. 154-159. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media/3 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film & Media Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cinema Journal 51 | No. 1 | Fall 2011 a neoliberal politics interested in citizens (and soldiers) who "do security" themselves. At the same time, we might come to recognize that our response to 9/ 1 1 has not been merely a product of political ideologies and institutions, but has also been motivated by a cultural logic of participation. The important questions to ask are not about whether 24 determined the war on terror or the other way around, but instead about the shared cultural and political protocols that laid the foundation for both. * Adapting Watchmen after 9/1 1 by Bob Rehak Every generation has its own reasons for destroying New York. - Max Page, The City's End 1 a very ambitious experiment in hyperfaithful cinematic adaptation. Taking its source, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's 1987 graphic Released Taking novel, novel, a very as script, as ambitious storyboard, in andits script,design bible, March the source,production storyboard, vowed experiment 2009, Alan Zack Moore and in Snyder's hyperfaithful and design Dave film bible, Gibbons's version the cinematic production of 1987 Watchmen adaptation. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

NO. In the Supreme Court of the United States LISA R. KIRBY, NEAL L. KIRBY, SUSAN N. KIRBY, BARBARA J. KIRBY, Petitioners, v. MARVEL CHARACTERS, INCORPORATED, MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INCORPORATED, MVL RIGHTS, LLC, WALT DISNEY COMPANY, MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, INCORPORATED, Respondents. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI MARC TOBEROFF Counsel of Record TOBEROFF & ASSOCIATES, P.C. 22337 Pacific Coast Hwy, Suite 348 Malibu, CA 90265 (310) 246-3333 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioners Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 i QUESTIONS PRESENTED The Copyright Act grants the children of a deceased author the right to recover the author’s copyrights by statutorily terminating prior copyright transfers. 17 U.S.C. §§ 304(c), (d). “Works for hire” are the sole exclusion. Id. Petitioners, the children of the acclaimed comic-book artist/creator Jack Kirby (The Fantastic Four, X-Men, The Mighty Thor, The Incredible Hulk, etc.), served statutory notices of termination on the Marvel respondents regarding the key works Kirby authored as an independent contractor in 1958-63. Section 26, the “work for hire” provision of the 1909 Copyright Act, applicable to pre-1978 works, states simply: “The word author shall include an employer in the case of works made for hire.” For six decades, including in 1958-63, “employer” was duly given its common law meaning, and “work for hire” applied solely to conventional employment, not to independent contractors like Kirby. It follows then, in 1958-63 Kirby was the original owner of the copyrights to the works he authored and subsequently assigned to Marvel, and his children have the right to recapture his copyrights by termination of such assignments under 17 U.S.C.§304(c). -

It's Garfield's World, We Just Live in It

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2019 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2019 It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast Iris B. Engel Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019 Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Animal Studies Commons, Arts Management Commons, Business Intelligence Commons, Commercial Law Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Economics Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, Folklore Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Engel, Iris B., "It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast" (2019). Senior Projects Fall 2019. 3. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019/3 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

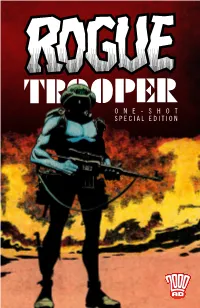

One-Shot Special Edition Script Gerry Finley-Day Guy Adams Art Dave Gibbons Darren Douglas Lee Carter Letters Simon Bowland Dave Gibbons

ONE-SHOT SPECIAL EDITION SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY GUY ADAMS ART DAVE GIBBONS DARREN DOUGLAS LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND DAVE GIBBONS REBELLION Creative Director and CEO Junior Graphic Novels Editor JASON KINGSLEY OLIVER BALL Chief Technical Officer Graphic Design CHRIS KINGSLEY SAM GRETTON, OZ OSBORNE & MAZ SMITH Head of Books & Comics Reprographics BEN SMITH JOSEPH MORGAN 2000 AD Editor in Chief PR & Marketing MATT SMITH MICHAEL MOLCHER Graphic Novels Editor Publishing Assistant KEITH RICHARDSON OWEN JOHNSON Rogue Trooper Published by Rebellion, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0ES. All contents © 1981, 2014, 2015, 2018 Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. All rights reserved. Rogue Trooper is a trademark of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form or by any means in whole or part without prior permission of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. is strictly forbidden. No similarity between any of the fictional names, characters, persons and/or institutions herein with those of any living or dead persons or institutions is intended (except for satirical purposes) and any such similarity is purely coincidental. ROGUE TROOPER SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY ART DAVE GIBBONS LETTERS DAVE GIBBONS ROGUE TROOPER DREGS OF WAR SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE FEAST SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE DEATH OF A DEMON SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND THE END ROGUE TROOPER GRAPHIC NOVELS FROM 2000 AD ROGUE TROOPER ROGUE -

Club Add 2 Page Designoct07.Pub

H M. ADVS. HULK V. 1 collects #1-4, $7 H M. ADVS FF V. 7 SILVER SURFER collects #25-28, $7 H IRR. ANT-MAN V. 2 DIGEST collects #7-12,, $10 H POWERS DEF. HC V. 2 H ULT FF V. 9 SILVER SURFER collects #12-24, $30 collects #42-46, $14 H C RIMINAL V. 2 LAWLESS H ULTIMATE VISON TP collects #6-10, $15 collects #0-5, $15 H SPIDEY FAMILY UNTOLD TALES H UNCLE X-MEN EXTREMISTS collects Spidey Family $5 collects #487-491, $14 Cut (Original Graphic Novel) H AVENGERS BIZARRE ADVS H X-MEN MARAUDERS TP The latest addition to the Dark Horse horror line is this chilling OGN from writer and collects Marvel Advs. Avengers, $5 collects #200-204, $15 Mike Richardson (The Secret). 20-something Meagan Walters regains consciousness H H NEW X-MEN v5 and finds herself locked in an empty room of an old house. She's bleeding from the IRON MAN HULK back of her head, and has no memory of where the wound came from-she'd been at a collects Marvel Advs.. Hulk & Tony , $5 collects #37-43, $18 club with some friends . left angrily . was she abducted? H SPIDEY BLACK COSTUME H NEW EXCALIBUR V. 3 ETERNITY collects Back in Black $5 collects #16-24, $25 (on-going) H The End League H X-MEN 1ST CLASS TOMORROW NOVA V. 1 ANNIHILATION A thematic merging of The Lord of the Rings and Watchmen, The End League follows collects #1-8, $5 collects #1-7, $18 a cast of the last remaining supermen and women as they embark on a desperate and H SPIDEY POWER PACK H HEROES FOR HIRE V. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Dundee Comics Day 2011

PRESS RELEASE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE ‘WOT COMICS TAUGHT ME…’ – DUNDEE COMICS DAY 2011 Judge Dredd creator John Wagner, and Frank Quietly, one of the world’s most sought-after comics artists, are among the top names appearing at this year’s Dundee Comics Day. They are just two of a number of star names from the world of comics lined up for the event, which will see talks, exhibitions, book signings and workshops take place as part of this year’s Dundee Literary Festival. Wagner started his long career as a comics writer at DC Thomson in Dundee before going on to revolutionise British comics in the late 1970s with the creation of Judge Dredd. He is the creator of Bogie Man, and the graphic novel A History of Violence, and has written for many of the major publishers in the US. Quietly has worked on New X-Men, We3, All-Star Superman, and Batman and Robin, as well as collaborating with some of the world’s top comics writers such as Mark Millar, Grant Morrison, and Alan Grant. His stylish artwork has made him one of the most celebrated artists in the comics industry. Wagner, Quietly and a host of other top industry talent will head to Dundee for the event, which will take place on Sunday, 30th October. Comics Day 2011 will be asking the question, what can comics teach us? Among the other leading industry figures giving their views on that subject will be former DC Thomson, Marvel, Dark Horse and DC Comics artist Cam Kennedy, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design graduate Colin MacNeil, who worked on various 2000AD and Marvel and DC Comics publications, such as Conan and Batman, and Robbie Morrison, creator of Nikolai Dante, one of the most beloved characters in recent British comics. -

Iron Man Ironheart

KUDRANSKI #1 MARVEL.COM DIRECT EDITION $4.99 T+ RATED IRON 0 0 1 1 1 BENDIS THE RUDY LEON US 7 59606 08710 5 IRONHEART IRON MAN IRON MAN KUDRANSKI VARIANT EDITION VARIANT #1 MARVEL.COM DIRECT EDITION $4.99 T+ RATED IRON 0 0 1 2 1 BENDIS THE RUDY LEON US 7 59606 08710 5 IRONHEART IRON MAN IRON MAN THE VANISHING POINT AN INSTANT APART! A MOMENT BEYOND! LOOSED FROM THE SHACKLES OF PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE— A PLACE WHERE TIME HAS NO MEANING! BUT WHERE TRUE INSIGHT CAN BE GAINED! MAKE YOUR CHOICE! SELECT YOUR DESTINATION! THIS JOURNEY IS A GIFT… WHEN TEEN PRODIGY AND GENIUS ENGINEER RIRI WILLIAMS GAINED BRIAN MICHAEL BENDIS NOTORIETY FOR CREATING HER OWN WRITER SUIT OF FLYING ARMOR, TONY STARK AGREED TO MENTOR HER ON HER PATH TO BECOMING A SUPER HERO. MARCO RUDY, SZYMON NOW SHE PROTECTS THE WORLD-- AND HER HOMETOWN OF CHICAGO-- KUDRANSKI & NICO LEON AS THE ONE-AND-ONLY PENCILERS SZYMON KUDRANSKI, WILL IRONHEART SLINEY, SCOTT KOBLISH & NICO LEON BILLIONAIRE PLAYBOY AND INKERS GENIUS INDUSTRIALIST TONY STARK WAS KIDNAPPED DURING MARCO RUDY, DEAN WHITE & A ROUTINE WEAPONS TEST. HIS CAPTORS ATTEMPTED TO FORCE PAUL MOUNTS HIM TO BUILD A WEAPON OF COLOR ARTISTS MASS DESTRUCTION. INSTEAD HE CREATED A POWERED SUIT OF ARMOR THAT SAVED HIS LIFE. VC’S CLAYTON COWLES FROM THAT DAY ON, HE USED THE LETTERER SUIT TO PROTECT THE WORLD AS THE INVINCIBLE AVENGER MARCO RUDY; OLIVIER COIPEL & LAURA MARTIN; JACK KIRBY, IRON DICK AYERS & PAUL MOUNTS WITH JOE FRONTIRRE MAN VARIANT COVER ARTISTS ALANNA SMITH ASSISTANT EDITOR THE IRON TOM BREVOORT EDITOR AXEL ALONSO GENERATIONS: IRON MAN & IRONHEART No.