Performativity of Rape Culture Through Fact and Fiction Main Text FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Violence in India: a Prajnya Report 2020

2020 1 GENDER VIOLENCE IN INDIA 2020 A Prajnya Report This report is an information initiative of the Gender Violence Research and Information Taskforce at Prajnya. This year’s report was prepared by Kausumi Saha whose work was supported by a donation in memory of R. Rajaram. It builds on previous reports authored over the years by: Kavitha Muralidharan, Zubeda Hamid, Shalini Umachandran, S. Shakthi, Divya Bhat, Titiksha Pandit, Mitha Nandagopalan, Radhika Bhalerao, Jhuma Sen and Suchaita Tenneti. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution and support of Gynelle Alves who has designed the report cover since 2009. © The Prajnya Trust 2020 2 CONTENTS GLOSSARY ................................................................................................................................................. 3 ABOUT THIS REPORT ................................................................................................................................ 5 GENDER VIOLENCE IN INDIA: STATISTICAL TABLE .................................................................................... 6 1. THE POLITICS OF SEXUAL AND GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE AGAINST DALIT WOMEN ....................... 12 2. PRE-NATAL SEX SELECTION / FEMALE FOETICIDE .............................................................................. 18 3. CHILD MARRIAGE, EARLY MARRIAGE AND FORCED MARRIAGE ........................................................ 24 4. HUMAN TRAFFICKING ....................................................................................................................... -

SIKH TIMES WEBSITE PAGE.Qxd

instagram.com/ @thesikhtimes facebook.com/ thesikhtimes qaumipatrika VISIT: PUBLISHED FROM Delhi, Haryana, Uttar www.thesikhtimes.in Pradesh, Punjab, The Sikh Times Email:[email protected] Chandigarh, Himachal and Jammu National Daily Vol. 13 No. 41 RNI NO. DELENG/2008/25465 New Delhi, Saturday, 26 June, 2021 [email protected] 9971359517 12 pages. 2/- Congress killed the world's largest democracy by imposing Emergency: Amit Shah on 46th anniversary Simmi Kaur Babbar New Delhi On June 25, 1975, the the coffin, that led to the imposition of then Prime Minister Indira the Emergency. Narayan called for Gandhi declared a state of Indira and the CMs to resign and the On June 25, 1975, the emergency across the country. military and police to disregard (June 25, 2021) marks the 46th unconstitutional and immoral orders. then Prime Minister anniversary of emergency's 'A dark chapter in the history of declaration, that remains one of independent India' Indira Gandhi declared a most debated and contested topic Union Home Minister Amit Shah on of independent India's political Friday remembered June 25 of 1975 state of Emergency history. Emergency was declared and said that the Emergency was for a 21-month period from 1975 imposed in the nation to quell the across the country. to 1977 by PM Indira Gandhi. voices against one family and termed it Officially issued by President as a dark chapter in the history of Home Minister Amit Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed under independent India. Taking to Twitter, Article 352 of the Constitution Shah said, "Emergency imposed to Shah took to social due to the prevailing "internal quell the voices against one family is a disturbance", the Emergency was dark chapter in the history of media (June 25, 2021) in effect from June 25, 1975, until independent India. -

CAA: Govt Open to Accept Suggestions of Protesters

Look at the sky. We are not alone. The whole universe is friendly to us SATURDAY and conspires only to give the best DECEMBER 21, 2019 to those who dream and work. CHANDIGARH VOL. XXIV, NO. 309 A. P. J. Abdul Kalam PAGES 8 Rs. 2 YUGMARGYOUR REGION, YOUR PAPER CAC to be formed in next Sanitation system to be kept intact Separate Narcotics Bureau to couple of days to appoint during solar eclipse fair: Subhash be set up in state: Vij selectors: Ganguly ....PAGE 3 ...PAGE 8 .... PAGE 3 CAA: Govt open to accept suggestions of protesters AGENCY Pakistan, Bangladesh and Asked about the protests tent authority that will handle the NEW DELHI, DEC 20 Afghanistan under the legisla- which have taken place in differ- applications of those who are go- tion. ent parts of the country, the offi- ing to apply for Indian citizen- The government is open to accept "We are open to receive sug- cial said as many as 59 petitions ship, and the entire process will suggestions, if any, from people gestions, if any, from anyone on were filed in the Supreme Court be digital. who are staging protests against the CAA. We are also trying to challenging the CAA and many "No one will get Indian citi- the Citizenship (Amendment) remove doubts of people about of these individuals and organisa- zenship automatically. One has to Act (CAA), a top official said on the CAA through various ways," tions which filed the pleas were prove eligibility," the official 6.3 magnitude Friday. the official said. -

'Others'-An Intersectional Analysis of Gender

This is the version of the article accepted for publication in Gender Issues published by Springer https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-019-09232-4 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/30770/ ‘Others’ within the ‘Others’-An Intersectional Analysis of Gender Violence in India Abstract In 2018, the rapes of two young girls shook India. The ruling government blatantly supported the perpetrators in both cases. It has also been highlighted that if the victims were high class, high caste or belonged to the Hindu community, public and media outrage would have been different, possibly similar to what was witnessed after the December 16th 2012, Delhi Nirbhaya rape. Hence, it is valid for us to question what was different about the Nirbhaya case? Class and caste divisions form the foundation of the hierarchical nature of Indian society. Using an analysis of the Nirbhaya rape case through the lens of intersectionality, this paper explores how factors such as class, caste, religion and geography in India influence not only how a case of gender violence and the victims are perceived but is also reflected on the perception of the perpetrators and the resultant punishments meted out. Previous research establishes interesting intersections of gender and representation in the Nirbhya case (Dey & Orton, 2016; Shandilya, 2015). This paper further builds on that discourse to establish how the intersection of social segregations along with gender division and patriarchy, form a complex web of discrimination and violence in India. Keywords: intersectionality, gender violence, rape, caste, class, patriarchy, Nirbhaya, India. Introduction India is an extensively diverse society with a wide range of intersecting discriminations affecting women. -

May Ank 2018 Curve

Tributes to Justice Sachar: Condolence Message on behalf of the ‘Indian Re- naissance Institute’ and ‘The Radical Humanist’ ‘Indian Renaissance Institute’ and ‘The Radical Humanist’ are deeply grieved over the sad demise of Justice Rajindar Sachar. From the very beginning of his life, whether as a socialist activist or a judge, he relentlessly pursued to promote the causes of the downtrodden, the marginalized sections and the minorities. He was a great source of strength to the objectives espoused by the Indian Renaissance Institute. He was a regular contributor to our monthly journal – ‘The Radical Humanist’. In his passing away the entire family of the radical humanists and several freedom loving citizens have lost a dear friend, philosopher and guide. Our heartfelt condolences to all the bereaved members of the family of Justice Sachar. Ramesh Awasthi Mahi Pal Singh Chairman, Editor, The Radical Humanist Indian Renaissance Institute 23rd April, 2018 Justice Rajindar Sachar – A Great Humanist N.D. Pancholi The news of Justice Sachar‘s demise on 20th on the issue of rising food prices. Habeas April 2018 came as a great shock. He was titan Corpus Petition was filed before the Punjab High among human rights champions and a pillar of court and it was argued by Justice Sachar. Court strength to secular democratic movement in the found the arrest as unlawful and ordered the country. In the early period of his life he was release of Madhu Limaye. Important legal actively involved in the socialist and trade union principles, impacting on the liberty of a person, movement. He combined activism with his legal emerged, which went on broadening with practice. -

Tearful Adieu to Coffee Tycoon

Follow us on: RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2019-21 @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 OPINION 8 WORLD 11 SPORT 15 Published From ESSENTIALS OF BUS STRIKES ROADSIDE BOMB IN ENG TO FACE AUS DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL BHUBANESWAR AFGHANISTAN, 32 KILLED RANCHI RAIPUR CHANDIGARH A GOOD HOST IN 1ST ASHES TEST DEHRADUN HYDERABAD VIJAYWADA Late City Vol. 155 Issue 209 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable LUCKNOW, THURSDAY AUGUST 1, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 SUPER 30 TAX-FREE IN MAHARASHTRA 14} VIVACITY } www.dailypioneer.com Tearful adieu to coffee tycoon CBI books Sengar CCD owner Siddhartha, whose body was fished out of Netravati river 2 days after he went missing, cremated for murder of rape KESTUR VASUKI/AGENCIES n im chief operating officer BENGALURU (COO) of the company, Coffee Day Enterprises, which runs he mystery over the where- India’s biggest coffee chain Tabouts of Cafe Coffee Day CCD, said in a regulatory filing. survivor’s aunts (CCD) owner VG Siddhartha CCD, India’s biggest coffee PNS n NEW DELHI Agency indicts nine — who went missing two days chain, is facing mounting debts ago — ended on a sombre note which topped almost `4,500 he CBI has booked Uttar others also for fatal with the recovery of his body crore. Though the group had TPradesh MLA Kuldeep from the Netravati River in raised debt from banks, mutu- Singh Sengar and nine others collision with Unnao Dakshina Kannada district on al funds and NBFCs among on murder charges in connec- Wednesday at 4.30 am. -

A Jurisprudential and Legislative Analysis of the Crime of Rape in India

An Open Access Journal from The Law Brigade Publishers 178 A JURISPRUDENTIAL AND LEGISLATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE CRIME OF RAPE IN INDIA Written by Ajinkya Deshmukh 4th year BBA-LLB(H) Student, Bennett University, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh ABSTRACT Rape, today is one of the biggest social problem not just in India but across the entire world as well. There are many theories; biological, psychological, and social, regarding why human show this bizarre trait of violent behavior towards the opposite sex. It is an unwanted biological feature? Or is it all about power and control over the opposite sex. There are also multiple speculations of rape being a gender biased hate crime, is there more to it? Is rape a passion driven act or something else? All these questions will be chronologically answered in the following research paper. The research paper also intends to cover the major and significant case laws which by far have contributed to the development of laws in India. Starting with the Mathura rape case, which has been a landmark judgment when it comes to the evolvement of jurisprudence in criminal law. It further giving birth to the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1983. Then leading to the famous Aruna Shanbaug rape case where the victim suffered lifetime injuries and the court blatantly rejected the contention of forced anal intercourse to be rape. Also throw some light upon the Bantala rape case which took place in 1990 where three female health officers, were assaulted in the utmost gruesome manner by CPI(M) party workers. The Nirbhaya rape case is a must when it comes to development of rape laws in India. -

Gender Socialization and Disempowerment of Women in India

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Theses Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-15-2020 Hinduism as a Political Weapon: Gender Socialization and Disempowerment of Women in India Aindrila Haldar University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/thes Part of the Epistemology Commons, Hindu Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Political Theory Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social Welfare Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Haldar, Aindrila, "Hinduism as a Political Weapon: Gender Socialization and Disempowerment of Women in India" (2020). Master's Theses. 1295. https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/1295 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hinduism as a Political Weapon: Gender Socialization and Disempowerment of Women in India In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS in INTERNATIONAL STUDIES by Aindrila Haldar March -

Sports News National News at AIIMS, Special Judge Holds Hearing To

Imphal Times Supplementary issue 4 National News North east News At AIIMS, Special Judge holds hearing to Centre constitutes MDC to look record Unnao rape survivor’s statement into development issues & Agency capital for treatment of injuries News agency PTI said law to deal with sexual offences New Delhi Sept.11, during a road accident in Uttar Sengar, who is a key against children. Pradesh. Her family alleged accused in the 2017 Unnao The Supreme Court ordered the district special needs Special Judge Dharmesh Kuldeep Singh Sengar was rape case, was also brought Central Bureau of Investigation to Sharma has reached the All behind the road accident in Rae to the temporary court carry out a quick probe into the road Courtesy TNT 15, however, there has been no specifies regarding seperate India Institute of Medical Bareli that killed two of her along with co-accused accident and shifted the trial of the Kohima September 11, dates fixed. Statehood and nothing else. Sciences to hold court aunts and injured the woman Shashi Singh for the rape case from Uttar Pradesh to The MDC after touring the Kekongchim Yimchünger, proceedings to record the and her lawyer. proceedings. Delhi. A Multi Disciplinary Committee districts held a closed door President ENPO said, “We will statement of the rape survivor Last week, the Delhi High Court Sengar was expelled from The road accident had put the (MDC) was constituted by the meeting with Eastern Naga not accept any development who had accused lawmaker issued a formal order allowing the Bharatiya Janata Party spotlight back on the survivor’s Centre on 12 June, 2019 to look People Organisation, Eastern packages if it is in line with the Kuldeep Singh Sengar of rape special judge Dharmesh last month after the family which, it turned out, had into the developmental aspects Naga Student’s Federation and Statehood demand but if it not in 2017. -

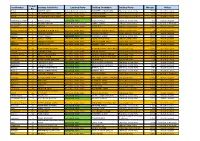

Onstituency Const. No. Leading Candidate Leading Party Trailing

Const. onstituency Leading Candidate Leading Party Trailing Candidate Trailing Party Margin Status No. Behat 1 NARESH SAINI Indian National Congress MAHAVEER SINGH RANA Bharatiya Janata Party 25586 Result Declared Nakur 2 DR.DHARAM SINGH SAINI Bharatiya Janata Party IMRAN MASOOD Indian National Congress 4057 Result Declared Nakur 2 DR.DHARAM SINGH SAINI Bharatiya Janata Party IMRAN MASOOD Indian National Congress 4057 Result Declared Saharanpur Nagar 3 SANJAY GARG Samajwadi Party RAJIV GUMBER Bharatiya Janata Party 4636 Result Declared Saharanpur 4 MASOOD AKHTAR Indian National Congress JAGPAL SINGH Bahujan Samaj Party 12324 Counting In Progress Deoband 5 BRIJESH Bharatiya Janata Party MAJID ALI Bahujan Samaj Party 29400 Result Declared Rampur Maniharan 6 DEVENDER KUMAR NIM Bharatiya Janata Party RAVINDRA KUMAR MOLHU Bahujan Samaj Party 595 Result Declared Gangoh 7 PRADEEP KUMAR Bharatiya Janata Party NAUMAN MASOOD Indian National Congress 38028 Result Declared Kairana 8 NAHID HASAN Samajwadi Party MRIGANKA SINGH Bharatiya Janata Party 21162 Result Declared Thana Bhawan 9 SURESH KUMAR Bharatiya Janata Party ABDUL WARIS KHAN Bahujan Samaj Party 16817 Result Declared Shamli 10 TEJENDRA NIRWAL Bharatiya Janata Party PANKAJ KUMAR MALIK Indian National Congress 29720 Result Declared Budhana 11 UMESH MALIK Bharatiya Janata Party PRAMOD TYAGI Samajwadi Party 13201 Result Declared Charthawal 12 VIJAY KUMAR KASHYAP Bharatiya Janata Party MUKESH KUMAR CHAUDHARY Samajwadi Party 23231 Result Declared Purqazi 13 PRAMOD UTWAL Bharatiya Janata Party -

I-T Unearths Hyd Company Link to VVIP Choppers Scam

Follow us on: RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer Established 1864 Published From ANALYSIS 9 TOLLYWOOD 13 SPORTS 16 HYDERABAD DELHI LUCKNOW THE SOCIOLOGY SHARWAA GIVES PRECEDENCE NEHWAL RETURNS BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH OF BANKING TO CHANDOO MONDETI WITH EASY WIN RANCHI BHUBANESWAR DEHRADUN VIJAYAWADA *LATE CITY VOL. 1 ISSUE 298 HYDERABAD, THURSDAY AUGUST 1, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable MLA SLAMS DEEPIKA, SHAHID FOR ‘DRUGGED STATE’ AT KJO PARTY { Page 11 } www.dailypioneer.com CJI allows CBI inquiry against I-T unearths Hyd company Will save discoms from HC judge NEW DELHI: Chief Justice financial crisis: CM KCR Ranjan Gogoi has permitted link to VVIP choppers scam the Central Bureau of L VENKAT RAM REDDY Investigation (CBI) to regis- PNS n NEW DELHI n HYDERABAD ter a case against S.N. Shukla, While the CBDT a judge of the Allahabad High The Income Tax Department Chief Minister K Court, for his alleged role in has unearthed fresh evidence statement did not Chandrasekhar Rao has assured a medical admission scam. in the VVIP choppers scam identify the company that the state government would Justice Shukla has become case after raiding a Hyderabad- provide the necessary financial the first sitting High Court based group, which purport- or its promoter, official support to power generation and judge to be investigated -- edly had dealings with Rajiv sources named the distribution companies in after a gap of nearly 28 years. Saxena, who has been arrested Hyderabad-based firm Telangana. He maintained that Justice Shukla has been in the case, the Central Board all the required measures will be Chief Minister K Chandrasekhar Rao presiding over a high-level meeting on accused of extending favours of Direct Taxes (CBDT) said as AlphaGeo and its taken to prevent electricity power sector at Pragathi Bhavan in Hyderabad on Wednesday to a private medical college by on Wednesday. -

UP Assembly Elections Results 2007

List of successful candidates in Uttar Pradesh Ac Ac Name Party Candidate Name No. 1 Seohara Bahujan Samaj Party YASH PAL SINGH 2 Dhampur Bahujan Samaj Party ASHOK KUMAR RANA 3 Afzalgarh Bahujan Samaj Party MUHAMMAD GAZI 4 Nagina Bahujan Samaj Party OMWATI DEVI 5 Nazibabad Bahujan Samaj Party SHEESH RAM SHAHNAWAZ S/O 6 Bijnor Bahujan Samaj Party BADRUJAMA 7 Chandpur Bahujan Samaj Party IQBAL 8 Kanth Bahujan Samaj Party RIZWAN AHMAD KHAN 9 Amroha Samajwadi Party MEHBOOB ALI 10 Hasanpur Bahujan Samaj Party FERHAT HASAN 11 Gangeshwari Bharatiya Janata Party HARPAL SINGH 12 Sambhal Samajwadi Party IQBAL MEHMOOD 13 Bahjoi Bahujan Samaj Party AQEEL-UR-RAHMAN KHAN 14 Chandausi Bahujan Samaj Party GIRISH CHANDRA 15 Kunderki Bahujan Samaj Party AKBAR HUSAIN 16 Moradabad West Bharatiya Janata Party RAJEEV CHANNA 17 Moradabad Samajwadi Party SANDEEP AGRAWAL 18 Moradabad Rural Samajwadi Party USMANUL HAQ VIJAY KUMAR URF VIJAY 19 Thakurdwara Bahujan Samaj Party YADAV NAWAB KAZIM ALI KHAN 20 Suar Tanda Samajwadi Party ALIAS NAVAID MIAN 21 Rampur Samajwadi Party MOHD. AZAM KHAN Indian National 22 Bilaspur SANJAY KAPOOR Congress 23 Shahabad Bharatiya Janata Party KASHI RAM Rashtriya Parivartan 24 Bisauli UMLESH YADAV Dal 25 Gunnaur Samajwadi Party MULAYAM SINGH YADAV Rashtriya Parivartan DHRAM PAL YADAV DP 26 Sahaswan Dal YADAV 27 Bilsi Bahujan Samaj Party YOGENDRA SAGAR URF ANU 28 Budaun Bharatiya Janata Party MAHESH CHANDRA 29 Usehat Bahujan Samaj Party MUSLIM KHAN 30 Binawar Bharatiya Jan Shakti RAM SEVAK SINGH SINOD KUMAR SHAKYA 31 Dataganj Bahujan