Shelf-Stable Foods Through Irradiation Processing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Identifying Meat Cuts

THE GUIDE TO IDENTIFYING MEAT CUTS Beef Eye of Round Roast Boneless* Cut from the eye of round muscle, which is separated from the bottom round. Beef Eye of Round Roast Boneless* URMIS # Select Choice Cut from the eye of round muscle, which is Bonelessseparated from 1the480 bottom round. 2295 SometimesURMIS referred # to Selectas: RoundChoic Eyee Pot Roast Boneless 1480 2295 Sometimes referred to as: Round Eye Pot Roast Roast, Braise,Roast, Braise, Cook in LiquidCook in Liquid BEEF Beef Eye of Round Steak Boneless* Beef EyeSame of muscle Round structure Steak as the EyeBoneless* of Round Roast. Same muscleUsually structure cut less than1 as inch the thic Eyek. of Round Roast. URMIS # Select Choice Usually cutBoneless less than1 1inch481 thic 2296k. URMIS #**Marinate before cooking Select Choice Boneless 1481 2296 **Marinate before cooking Grill,** Pan-broil,** Pan-fry,** Braise, Cook in Liquid Beef Round Tip Roast Cap-Off Boneless* Grill,** Pan-broil,** Wedge-shaped cut from the thin side of the round with “cap” muscle removed. Pan-fry,** Braise, VEAL Cook in Liquid URMIS # Select Choice Boneless 1526 2341 Sometimes referred to as: Ball Tip Roast, Beef RoundCap Off Roast, Tip RoastBeef Sirloin Cap-Off Tip Roast, Boneless* Wedge-shapedKnuckle Pcuteeled from the thin side of the round with “cap” muscle removed. Roast, Grill (indirect heat), Braise, Cook in Liquid URMIS # Select Choice Boneless Beef Round T1ip526 Steak Cap-Off 234 Boneless*1 Same muscle structure as Tip Roast (cap off), Sometimesbut cutreferred into 1-inch to thicas:k steaks.Ball Tip Roast, Cap Off Roast,URMIS # Beef Sirloin Select Tip ChoicRoast,e Knuckle PBonelesseeled 1535 2350 Sometimes referred to as: Ball Tip Steak, PORK Trimmed Tip Steak, Knuckle Steak, Peeled Roast, Grill (indirect heat), **Marinate before cooking Braise, Cook in Liquid Grill,** Broil,** Pan-broil,** Pan-fry,** Stir-fry** Beef Round Tip Steak Cap-Off Boneless* Beef Cubed Steak Same muscleSquare structureor rectangula asr-shaped. -

Effects of Acute and Chronic Gamma Irradiation on the Cell Biology and Physiology of Rice Plants

plants Article Effects of Acute and Chronic Gamma Irradiation on the Cell Biology and Physiology of Rice Plants Hong-Il Choi 1,† , Sung Min Han 2,†, Yeong Deuk Jo 1 , Min Jeong Hong 1 , Sang Hoon Kim 1 and Jin-Baek Kim 1,* 1 Advanced Radiation Technology Institute, Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, Jeongeup 56212, Korea; [email protected] (H.-I.C.); [email protected] (Y.D.J.); [email protected] (M.J.H.); [email protected] (S.H.K.) 2 Division of Ecological Safety, National Institute of Ecology, Seocheon 33657, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-63-570-3313 † Both authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: The response to gamma irradiation varies among plant species and is affected by the total irradiation dose and dose rate. In this study, we examined the immediate and ensuing responses to acute and chronic gamma irradiation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice plants at the tillering stage were exposed to gamma rays for 8 h (acute irradiation) or 10 days (chronic irradiation), with a total irradiation dose of 100, 200, or 300 Gy. Plants exposed to gamma irradiation were then analyzed for DNA damage, oxidative stress indicators including free radical content and lipid peroxidation, radical scavenging, and antioxidant activity. The results showed that all stress indices increased immediately after exposure to both acute and chronic irradiation in a dose-dependent manner, and acute irradiation had a greater effect on plants than chronic irradiation. The photosynthetic efficiency and growth of plants measured at 10, 20, and 30 days post-irradiation decreased in irradiated plants, Citation: Choi, H.-I.; Han, S.M.; Jo, Y.D.; Hong, M.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.-B. -

Effects of Gamma-Irradiation of Seed Potatoes on Numbers of Stems and Tubers

Netherlands Journal of Agricultural Science 39 (1991) 81-90 Effects of gamma-irradiation of seed potatoes on numbers of stems and tubers A. J. HAVERKORT1, D. I. LANGERAK2 & M. VAN DE WAART1 1 Centre for Agrobiological Research (CABO-DLO), P.O. Box 14, NL 6700 AA Wagenin- gen, Netherlands 2 State Institute for Quality Control of Agricultural Products (RIKILT), P.O. Box 230, NL 6700 AE Wageningen, Netherlands Received 28 november 1990; accepted 8 February 1991 Abstract In field trials with the cultivars Bintje, Jaerla and Spunta, whose seed potatoes were treated with gamma-rays from a ^Co source with doses varying from 0.5 to 27 Gy, tuber yield, har vest index, and number of stems and tubers were determined. A dose of 3 Gy increased the number of tubers by 30 % in Spunta in two out of three trials and by 17 % in one trial in Jaer la, but it did not increase number of tubers in Bintje. Doses of 9 or 10 Gy did not influence the number of tubers nor stems, and decreased harvest index. A dose of 27 Gy yielded off-type plants with reduced yield and number of tubers. Gamma-radiation affected the growth of the apex of the sprout allowing lateral buds or divisions of the affected apex to develop into stems. To achieve larger numbers of tuber-bearing stems, tubers should preferably be irra diated at the start of sprout growth, about 5 months before planting. Keywords: harvest index, gamma irradiation, seed potatoes Introduction Effects of different doses of gamma-rays on potato tubers have been studied exten sively, especially in the 1960s. -

Industrial Applications of Electron Accelerators

Industrial applications of electron accelerators M.R. Cleland Ion Beam Applications, Edgewood, NY 11717, USA Abstract This paper addresses the industrial applications of electron accelerators for modifying the physical, chemical or biological properties of materials and commercial products by treatment with ionizing radiation. Many beneficial effects can be obtained with these methods, which are known as radiation processing. The earliest practical applications occurred during the 1950s, and the business of radiation processing has been expanding since that time. The most prevalent applications are the modification of many different plastic and rubber products and the sterilization of single-use medical devices. Emerging applications are the pasteurization and preservation of foods and the treatment of toxic industrial wastes. Industrial accelerators can now provide electron energies greater than 10 MeV and average beam powers as high as 700 kW. The availability of high-energy, high-power electron beams is stimulating interest in the use of X-rays (bremsstrahlung) as an alternative to gamma rays from radioactive nuclides. 1 Introduction Radiation processing can be defined as the treatment of materials and products with radiation or ionizing energy to change their physical, chemical or biological characteristics, to increase their usefulness and value, or to reduce their impact on the environment. Accelerated electrons, X-rays (bremsstrahlung) emitted by energetic electrons, and gamma rays emitted by radioactive nuclides are suitable energy sources. These are all capable of ejecting atomic electrons, which can then ionize other atoms in a cascade of collisions. So they can produce similar molecular effects. The choice of energy source is usually based on practical considerations, such as absorbed dose, dose uniformity (max/min) ratio, material thickness, density and configuration, processing rate, capital and operating costs. -

Bio-9 a Comparison of Y-Irradiation and Microwave Treatments on the Lipids and Microbiological Pattern of Beef Liver

Seventh Conference of Nuclear Sciences & Applications 6-10 February 2000, Cairo, Egypt Bio-9 A comparison of y-irradiation and microwave treatments on the lipids and microbiological pattern of beef liver Farag, R. S .*, Z. Y. Daw2, Farag , S.A 3 and Safaa A. E. ABD El-Wahab3. / Biochemistry Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Cairo University, Giza - Egypt. 2 Microbiology Department. Faculty of Agriculture. Cairo University, Giza - Egypt. 3 Food irradiation Department, National Center for Radiation Research and Technology, Cairo - Egypt. ABSTRACT EG0100123 The effects of y-irradiation treatments (0, 2.5, 5 and, 10 kGy) and microwaves generated from an oven at low and defrost settings for 0.5 , 1 and 2 min on the chemical composition and microbiological aspects of beef liver samples were studied . The chemical and microbiological analyses were performed on the non-treated and treated beef liver immediately after treatments and during frozen storage (-18°C) for 3 months. The chemical analyses of beef liver Hpids showed that acid, peroxide and TBA(Thiobarbituric acid ) values were slightly increased after irradiation treatments and also during frozen storage (-18°C). On the contrary, iodine value of the treated beef liver was decreased. Irradiation treatments remarkably reduced the total bacterial counts in beef liver. The percent reduction of bacterial load for beef liver exposed to microwaves generated from an oven at defrost mode for 2 min and after 3 months at - 18°C was 62% . The bacterial load for beef liver exposed to y-irradiation at 10 kGy after 3 months at - 18°C was decreased by 98%. Hence, y-irradiation treatment was far better than microwave treatment for inhibiting the multiplication of the associated microorganisms with beef liver. -

12 Steak Tartare

November 22nd, 2018 3 Course Menu, $42 per person ( tax & gratuity additional ) ( no substitutions, no teal deals, thanksgiving day menu is a promotional menu ) Salad or Soup (choice, descriptions below) Caesar Salad, Wedge Salad, Lobster Bisque or Italian White Bean & Kale Entrée (choice, descriptions below) Herb Roasted Turkey, Local Flounder, Faroe Island Salmon or Braised Beef Short Rib Dessert (choice) Dark Chocolate Mousse Cake, Old Fashioned Carrot Cake, Pumpkin Cheesecake, Cinnamon Ice Cream, Vanilla Ice Cream or Raspberry Sorbet A LA CARTE MENU APPETIZERS ENTREES Butternut Squash & Gouda Arancini … 13 Herb Roasted Fresh Turkey … 32 (5) risotto arancini, asparagus pesto, truffle oil, mashed potato, herbed chestnut stuffing, fried sage, aged pecorino Romano glazed heirloom carrots, haricot vert, truffled brown gravy, cranberry relish Smoked Salmon Bruschetta … 12 house smoked Faroe Island salmon, lemon aioli, Local Flounder … 32 micro salad with shallot - dill vinaigrette, crispy capers warm orzo, sweet corn, sun dried tomato, edamame & vidalia, sautéed kale, bell pepper-saffron jam, basil pesto Steak Tartare … 14 beef tenderloin, sous vide egg yolk, caper, Faroe Island Salmon* … 32 shallot, lemon emulsion, parmesan dust, garlic loaf toast roasted spaghetti squash, haricot vert & slivered almonds, carrot puree, garlic tomato confit, shallot dill beurre blanc Grilled Spanish Octopus … 14 gigante bean & arugula sauté, grape tomatoes, Boneless Beef Short Rib … 32 salsa verde, aged balsamic reduction oyster mushroom risotto, sautéed -

Beam–Material Interactions

Beam–Material Interactions N.V. Mokhov1 and F. Cerutti2 1Fermilab, Batavia, IL 60510, USA 2CERN, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract This paper is motivated by the growing importance of better understanding of the phenomena and consequences of high-intensity energetic particle beam interactions with accelerator, generic target, and detector components. It reviews the principal physical processes of fast-particle interactions with matter, effects in materials under irradiation, materials response, related to component lifetime and performance, simulation techniques, and methods of mitigating the impact of radiation on the components and environment in challenging current and future applications. Keywords Particle physics simulation; material irradiation effects; accelerator design. 1 Introduction The next generation of medium- and high-energy accelerators for megawatt proton, electron, and heavy- ion beams moves us into a completely new domain of extreme energy deposition density up to 0.1 MJ/g and power density up to 1 TW/g in beam interactions with matter [1, 2]. The consequences of controlled and uncontrolled impacts of such high-intensity beams on components of accelerators, beamlines, target stations, beam collimators and absorbers, detectors, shielding, and the environment can range from minor to catastrophic. Challenges also arise from the increasing complexity of accelerators and experimental set-ups, as well as from design, engineering, and performance constraints. All these factors put unprecedented requirements on the accuracy of particle production predictions, the capability and reliability of the codes used in planning new accelerator facilities and experiments, the design of machine, target, and collimation systems, new materials and technologies, detectors, and radiation shielding and the minimization of radiation impact on the environment. -

![Particle Accelerators and Detectors for Medical Diagnostics and Therapy Arxiv:1601.06820V1 [Physics.Med-Ph] 25 Jan 2016](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8515/particle-accelerators-and-detectors-for-medical-diagnostics-and-therapy-arxiv-1601-06820v1-physics-med-ph-25-jan-2016-558515.webp)

Particle Accelerators and Detectors for Medical Diagnostics and Therapy Arxiv:1601.06820V1 [Physics.Med-Ph] 25 Jan 2016

Particle Accelerators and Detectors for medical Diagnostics and Therapy Habilitationsschrift zur Erlangung der Venia docendi an der Philosophisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at der Universit¨atBern arXiv:1601.06820v1 [physics.med-ph] 25 Jan 2016 vorgelegt von Dr. Saverio Braccini Laboratorium f¨urHochenenergiephysik L'aspetto pi`uentusiasmante della scienza `eche essa incoraggia l'uomo a insistere nei suoi sogni. Guglielmo Marconi Preface This Habilitation is based on selected publications, which represent my major sci- entific contributions as an experimental physicist to the field of particle accelerators and detectors applied to medical diagnostics and therapy. They are reprinted in Part II of this work to be considered for the Habilitation and they cover original achievements and relevant aspects for the present and future of medical applications of particle physics. The text reported in Part I is aimed at putting my scientific work into its con- text and perspective, to comment on recent developments and, in particular, on my contributions to the advances in accelerators and detectors for cancer hadrontherapy and for the production of radioisotopes. Dr. Saverio Braccini Bern, 25.4.2013 i ii Contents Introduction 1 I 5 1 Particle Accelerators and Detectors applied to Medicine 7 2 Particle Accelerators for medical Diagnostics and Therapy 23 2.1 Linacs and Cyclinacs for Hadrontherapy . 23 2.2 The new Bern Cyclotron Laboratory and its Research Beam Line . 39 3 Particle Detectors for medical Applications of Ion Beams 49 3.1 Segmented Ionization Chambers for Beam Monitoring in Hadrontherapy 49 3.2 Proton Radiography with nuclear Emulsion Films . 62 3.3 A Beam Monitor Detector based on doped Silica Fibres . -

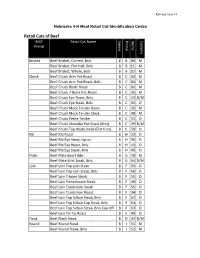

Retail Cuts of Beef BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal

Revised June 14 Nebraska 4-H Meat Retail Cut Identification Codes Retail Cuts of Beef BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal Brisket Beef Brisket, Corned, Bnls B B 89 M Beef Brisket, Flat Half, Bnls B B 15 M Beef Brisket, Whole, Bnls B B 10 M Chuck Beef Chuck Arm Pot-Roast B C 03 M Beef Chuck Arm Pot-Roast, Bnls B C 04 M Beef Chuck Blade Roast B C 06 M Beef Chuck 7-Bone Pot-Roast B C 26 M Beef Chuck Eye Roast, Bnls B C 13 D/M Beef Chuck Eye Steak, Bnls B C 45 D Beef Chuck Mock Tender Roast B C 20 M Beef Chuck Mock Tender Steak B C 48 M Beef Chuck Petite Tender B C 21 D Beef Chuck Shoulder Pot Roast (Bnls) B C 29 D/M Beef Chuck Top Blade Steak (Flat Iron) B C 58 D Rib Beef Rib Roast B H 22 D Beef Rib Eye Steak, Lip-on B H 50 D Beef Rib Eye Roast, Bnls B H 13 D Beef Rib Eye Steak, Bnls B H 45 D Plate Beef Plate Short Ribs B G 28 M Beef Plate Skirt Steak, Bnls B G 54 D/M Loin Beef Loin Top Loin Steak B F 59 D Beef Loin Top Loin Steak, Bnls B F 60 D Beef Loin T-bone Steak B F 55 D Beef Loin Porterhouse Steak B F 49 D Beef Loin Tenderloin Steak B F 56 D Beef Loin Tenderloin Roast B F 34 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Steak, Bnls B F 62 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Cap Steak, Bnls B F 64 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Steak, Bnls Cap Off B F 63 D Beef Loin Tri-Tip Roast B F 40 D Flank Beef Flank Steak B D 47 D/M Round Beef Round Steak B I 51 M Beef Round Steak, Bnls B I 52 M BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal Beef Bottom Round Rump Roast B I 09 D/M Beef Round Top Round Steak B I 61 D Beef Round Top Round Roast B I 39 D Beef -

Beef Steak Different Names

Beef Steak Different Names SHORT LOIN T‐Bone/Porterhouse Club Steak Tenderloin Steak Also Known As: Filet Mignon Fillet de Boeuf Fillet Steak Tournados Medallions Top Loin Steak, Boneless Also Known As: Ambassador Steak Strip Steak Boneless Club Steak Hotel‐Style Steak Kansas City Steak NY Strip Steak Veiny Steak Top Loin Steak, Bone‐in Also Known As: Sirloin Strip Steak Delmonico Steak Chip‐Club Steak Country Club Steak Strip Steak Shell Steak RIB Rib Steak RIB‐EYE STEAK Also Known As: Beauty Steak Delmonico Steak Market Steak Spencer Steak PLATE Skirt Steak ‐ is actually the diaphragm muscle that is cut into portions weighing about 1½ pounds each. This less tender cut benefits from a tenderizing marinade and should be carved across the grain into thin slices for serving. Skirt steak is the original cut used for fajitas. Also Known As: Fajita Meat Inside Skirt Steak Outside Skirt Steak Philadelphia Steak BEEF HANGER STEAK This steak is part of the diaphragm muscle and is best served rare or medium rare. This is a large, thin, flat steak that is great marinated and is flavorful and chewy. Slice it thinly across the grain to serve. Broil, Panfry or Stir‐fry Also Known As: Beef "Hanging Tender". Also sometimes spelled "Hangar" Steak. Hanging Tenderloin Butcher’s Steak FLANK Also Known As: Flank Steak Flank Steak Fillet Jiffy Steak London Broil SIRLOIN [Baron of Beef ‐ Large Roast of the Whole Sirloin Not Cut Down The Backbone] Also Known As: Sirloin Steak Flat‐Bone Steak Pin‐Bone Steak Round‐Bone Steak Wedge‐Bone Steak Top Sirloin Steak, -

Meat Quality Workshop: Know Your Muscle, Know Your Meat BEEF

2/6/2017 Meat Quality Workshop: Know Your Muscle, Know Your Meat Principles of Muscle Profiling, Aging, and Nutrition Dale R. Woerner, Ph.D., Colorado State University BEEF- Determining Value 1 2/6/2017 Slight00 Small00 Modest00 Moderate00 SLAB00 MAB00 ACE ABC Maturity Group Approximate Age A 9‐30 months B 30‐42 months C 42‐72 months D E 72‐96 months 96 months or older Augmentation of USDA Grade Application 2 2/6/2017 Effect of Marbling Degree on Probability of a Positive Sensory Experience Probability of a Positive Sensory Experience 0.99a 0.98a 1 0.88b 0.9 0.82b 0.8 0.7 0.62c 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.29d 0.3 0.2 0.15e 0.1 0 TR SL SM MT MD SA MA Colorado State University M.S. Thesis: M. R. Emerson (2011) 3 2/6/2017 Carcass Weight Trend 900 All Fed Cattle CAB® 875 850 +55 lbs. in 5 years 825 +11 lbs. / year 800 775 750 +117 lbs. in 20 years Hot Carcass (lbs.) Weight +5.8 lbs. / year 725 Year 4 2/6/2017 Further Problems • Food service portion cutting problems = 8 oz. • Steak preparation problems = 8 oz. A 1,300‐pound, Yield Grade 3 steer yields 639 pounds of retail cuts from an 806‐pound carcass. Of the retail cuts, 62% are roasts and steaks (396 pounds) and 38% are ground beef and stew meat (243 pounds). 5 2/6/2017 Objective of Innovative Fabrication • Use quality-based break points during fabrication • Add value to beef by optimizing use of high-quality cuts • Add value to beef cuts by improving leanness and portion size $2.25 $7.56 $2.75 $4.66 $2.50 $12.73 $2.31 $2.85 $3.57 $1.99 Aging Response Premium USDA Choice USDA Select Muscle Aging response -

Fabulous & Creative Food Precise & Attentive Service

FABULOUS & CREATIVE FOOD PRECISE & ATTENTIVE SERVICE BEAUTIFUL & INTERESTING EVENT SPACES Thank you for considering Padre Hotel to host your event. Our dynamic team of chefs and event coordinators will work with you to create a menu the perfectly captures your vision. We believe food should be a reflection of both your purpose and personality. Our professional staff brings decades of experience to the table. We are inspired by the simplicity of the classics. Our chefs source the best ingredients and work with exceptional local purveyors to give your event the attention to detail that is the signature of Padre Hotel hospitality. Ready to start planning, phone: 661-427-4900 email: [email protected] padre hotel 1702 18TH STREET, BAKERSFIELD CA 93301 WEB THEPADREHOTEL.COM TEL 661–427–4900 E [email protected] The Padre Hotel will customize your morning. FARMERS’ DAUGHTER BUFFET We offer a variety of breakfast buffets, brunch offerings $18 Per Person and can fly you to your next stop with breakfast on Scrambled Eggs, Buttermilk Fried Chicken, the go. Buffets include a full service pastry team to Fresh House Made Biscuits, Sausage Gravy, maximize your catering needs. From fresh baked muffins to steak and eggs, The Padre Hotel looks forward to Applewood Smoked Bacon, Breakfast Sausage Links, waking up with you. Country Potatoes, Fresh Fruit Salad, Coffee Station, Orange Juice 25 person minimum. EL HEFE BREAKFAST BUFFET CALI CONTINENTAL BUFFET $18 Per Person $11 Per Person Cotija Scrambled Eggs, Chilaquiles Rojo, House Baked Pastries,