The Restaurant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Honeymoon Cottages At

Guy Harvey RumFish Grill Joins the Team at Amalie Arena Restaurant opens branded concession stand at arena in November TAMPA, Fla. (November 20, 2014) – Guy Harvey RumFish Grill recently opened a branded concession area at the Amalie Arena, formerly the Tampa Bay Times Forum, home to the NHL’s Tampa Bay Lightning and the Arena Football League’s Tampa Bay Storm. The St. Pete Beach restaurant has a full-service concession area serving spicy firecracker shrimp, blue crab bisque, BBQ short rib flatbread, blackened fish sandwich and other popular menu items. The RumFish Grill also has a full-bar area across the aisle where thirsty fans can enjoy the signature beach-themed Blue Marlin, other mixed drinks and multiple beers on tap including Corona Light and Beach Blonde Ale from 3 Daughters Brewing, a fast-growing, St. Pete-based craft brewery known for their innovative brews for beer lovers. Although the new concession space does not have the St. Pete Beach restaurant’s famous fish tanks, it will be heavily themed and decorated with aquatic murals, marlin mounts, beach photography and large television monitors. “We’re very happy with the success of the RumFish Grill at Guy Harvey Outpost on St. Pete Beach and wanted to share it with an audience across the bridge,” said Keith Overton, president of TradeWinds Island Resorts. “We look forward to bringing the flavors of the beach to the patrons at Amalie Arena.” As part of the sponsorship with Amalie Arena and the Tampa Bay Lightning, RumFish Grill will also host food samplings in select areas such as the Chase Club, have a representative at all home games to promote TradeWinds, and participate in promotions during the games and on the post-game radio show and more. -

Nude in Mexico

Feb. 1, 2004---- RIVIERA MAYA, MEXICO -- The road is full of questions that inevitably lead to the beauty of travel. This is how I find myself leaning on a bar at the Moonlight disco at the Hidden Beach Resort-Au Naturel Club, the only upscale and not clothing- optional nudist resort in Mexico. A naked woman walks up to me and asks, "Is this your first naked experience?" Gee, how can she tell? I am standing in a corner of the bar that is under a shadow of doubt. About 20 naked couples have finished doing a limbo dance on a cool night along the Caribbean Sea. With the exception of a gentleman from Mexico, I am the only single guy in the disco. At this point, no one knows I am a journalist, but I am the only person in the room still wearing a bathrobe. It is too cold to be bold. Besides, I am so shy, I do not limbo with my clothes on. I barely ever go to clothed cocktail parties. My chipper friends are also mastering "The Macarena." Talk about your Polaroid moments. Cameras are not allowed at Hidden Beach. One dude is playing pool naked. Another guy looks like Jeff "Curb Your Enthusiasm" Garlin. His wife is applying for a job at Hidden Beach. He smiles and takes off his robe to join in a group dance to Marcia Griffith's "Electric Boogie." Nude tourists are more open and they bond faster. I have another shot of tequila. I am here for you. The nude recreation industry is news. -

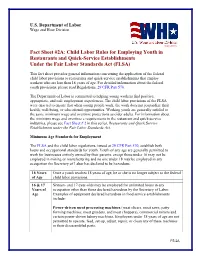

Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division (July 2010) Fact Sheet #2A: Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) This fact sheet provides general information concerning the application of the federal child labor provisions to restaurants and quick-service establishments that employ workers who are less than 18 years of age. For detailed information about the federal youth provisions, please read Regulations, 29 CFR Part 570. The Department of Labor is committed to helping young workers find positive, appropriate, and safe employment experiences. The child labor provisions of the FLSA were enacted to ensure that when young people work, the work does not jeopardize their health, well-being, or educational opportunities. Working youth are generally entitled to the same minimum wage and overtime protections as older adults. For information about the minimum wage and overtime e requirements in the restaurant and quick-service industries, please see Fact Sheet # 2 in this series, Restaurants and Quick Service Establishment under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Minimum Age Standards for Employment The FLSA and the child labor regulations, issued at 29 CFR Part 570, establish both hours and occupational standards for youth. Youth of any age are generally permitted to work for businesses entirely owned by their parents, except those under 16 may not be employed in mining or manufacturing and no one under 18 may be employed in any occupation the Secretary of Labor has declared to be hazardous. 18 Years Once a youth reaches 18 years of age, he or she is no longer subject to the federal of Age child labor provisions. -

Government, Civil Society and Private Sector Responses to the Prevention of Sexual Exploitation of Children in Travel and Tourism

April 2016 Government, civil society and private sector responses to the prevention of sexual exploitation of children in travel and tourism A Technical Background Document to the Global Study on Sexual Exploitation of Children in Travel and Tourism Child Protection Section, Programme Division, UNICEF Headquarters ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ‘ The paper was prepared by Clara Sommarin (Child Protection Specialist, Programme Division, UNICEF Headquarters), Frans de Man and Amaya Renobales (independent consultants) and Jeanette Trang (intern Child Protection Section, Programme Division, UNICEF Headquarters) and copyedited by Alison Raphael. FRONT COVER: On 14 March 2016, a young vendor walks along a highly trafficked street in the heart of the city of Makati’s “red light district,” in Metro Manila, Philippines. Makati is considered the financial and economic centre of Manila, and is also a hub for sexual exploitation in the context of travel and tourism. © UNICEF/UN014913/Estey FACING PAGE: [NAME CHANGED] Rosie, 16, in Dominica in the eastern Caribbean on 8 July 2017. Rosie was 15 yrs old when she underwent sexual abuse. © UNICEF/UN0142224/Nesbitt i CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTERNATIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR ACTION .................................................................... 3 2.1 International Human Rights Standards ................................................................................... 3 2.2 Global Political Commitments -

DS-2026 Hotel and Restaurant Report

U.S. Department of State Office of Allowances Hotel and Restaurant Report INSTRUCTIONS The information provided in this report will be used to determine the travel Per Diem Allowance. Please complete and sign the Post Information section, as well as Sections 1 and 2. The instructions below correspond to the required data fields in Sections 1 and 2. COMPLETING THE REPORT: General Instructions (a) The Hotel and Restaurant Report (DS-2026) is used to determine the maximum travel allowances. It is to be submitted by civilian Federal agencies in accordance with Sections 070 and 920 of the Department of State Standardized Regulations (DSSR). Reports submitted by Uniformed Service members must follow the procedures provided in Appendix M of the Joint Federal Travel Regulations. (b) Report all prices in the currency required by the facility. Provide explanation in the Comments section if the hotel and/or meal prices are quoted in U.S. dollars. Round the tax rate, service charge, or tip rate percentages to two digits. (c) If there are no suitable hotel or restaurant facilities within a reasonable distance (including hostels and guest houses), include under Comments (Sections 1 and 2) a statement about the arrangements made for travelers. Typical room rates refer to discounted room rates most often given to United States Government (USG) travelers. Typical meals refer to basic food items most often consumed by USG travelers. Section 1 - Hotels (a) List prices for moderately priced hotels that are frequently used by USG employees and reported in the post log or by the military billeting office. Post should select hotels that meet U.S. -

Preliminary Pages

! ! UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ! RIVERSIDE! ! ! ! ! Tiny Revolutions: ! Lessons From a Marriage, a Funeral,! and a Trip Around the World! ! ! ! A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction ! of the requirements! for the degree of ! ! Master of !Fine Arts ! in!! Creative Writing ! and Writing for the! Performing Arts! by!! Margaret! Downs! ! June !2014! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Thesis Committee: ! ! Professor Emily Rapp, Co-Chairperson! ! Professor Andrew Winer, Co-Chairperson! ! Professor David L. Ulin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Copyright by ! Margaret Downs! 2014! ! ! The Thesis of Margaret Downs is approved:! ! !!_____________________________________________________! !!! !!_____________________________________________________! ! Committee Co-Chairperson!! !!_____________________________________________________! Committee Co-Chairperson!!! ! ! ! University of California, Riverside!! ! !Acknowledgements ! ! Thank you, coffee and online banking and MacBook Air.! Thank you, professors, for cracking me open and putting me back together again: Elizabeth Crane, Jill Alexander Essbaum, Mary Otis, Emily Rapp, Rob Roberge, Deanne Stillman, David L. Ulin, and Mary Yukari Waters. ! Thank you, Spotify and meditation, sushi and friendship, Rancho Las Palmas and hot running water, Agam Patel and UCR, rejection and grief and that really great tea I always steal at the breakfast buffet. ! Thank you, Joshua Mohr and Paul Tremblay and Mark Haskell Smith and all the other writers who have been exactly where I am and are willing to help. ! And thank you, Tod Goldberg, for never being satisfied with what I write. !Dedication! ! ! For Misty. Because I promised my first book would be for you. ! For my hygges. Because your friendship inspires me and motivates me. ! For Jason. Because every day you give me the world.! For Everest. Because. !Table of Contents! ! ! !You are braver than you think !! ! ! ! ! ! 5! !When you feel defeated, stop to catch your breath !! ! ! 26! !Push yourself until you can’t turn back !! ! ! ! ! 40! !You’re not lost. -

Sweet Honeymoons at Caramel

Sweet Honeymoons at Caramel SWEETNESS OF LIFE … From the moment you check-in as husband and wife, we promise you an unforgettable experience. The sparkling blue sea, twinkling stars, sensuously decorated suites & villas and discrete service will make your honeymoon a once in a lifetime experience. Luxuriate in a romantic breakfast served on your secluded veranda before soaking up the sun beside your private pool. The Caramel, Grecotel Boutique Resort is unique: a suite & villa hotel on the glorious 14 km sandy beach near Rethymno, Crete. Once you have chosen your accommodation & honeymoon package, your biggest choice will be whether to relax by the pools or sea for your honeymoon… or to experience unforgettable moments. Couples who also celebrate their wedding at the hotel will receive a 20% discount on the Honeymoon packages. Please note that the honeymoon options are complete packages and items are not interchangeable. In the event that you decide not to use one of the services, no refund or alternative can be given. Prices include all local taxes at current rate. ROSE GARDEN HONEYMOON – FREE* A refreshing welcome drink upon arrival at the hotel Honeymoon welcome with chilled sparkling wine and fresh fruits waiting in your guestroom Special decoration of the honeymoon bed with sugared almonds & scented rose petals “Melokarido” – a Greek tradition of honey and walnuts, symbolizing virility and the sweetness of life Romantic continental breakfast served in the privacy of your room the next morning Room upgrade upon availability * Valid for all Grecotel Hotels & Resorts (5* & 4*). To enjoy this free offer, inform the hotel up to 14 days before your arrival and present a copy of your wedding certificate (dated within last 12 months) at reception. -

Imagining Others: Sex, Race, and Power in Transnational Sex Tourism

Imagining Others: Sex, Race, and Power in Transnational Sex Tourism Megan Rivers-Moore1 Women and Gender Studies Institute University of Toronto [email protected] Abstract While most research into the sex tourism industry focuses on the often stark inequalities that exist between sex tourists and sex workers, there are a plethora of other subjects that are involved in the complicated web of transnational interactions involving travel and sex. This article focuses on the ways in which other subjects who may not actually be present in sex tourism spaces are constructed and put to use in the context of sex tourism. The aim is to explore the ways in which sex tourists and sex workers imagine and invoke two specific groups, Costa Rican men and North American women, in order to make meaning out of their encounters with one another. The article asks how these imagined others are implicated in sex tourism and how they are made present in ways that enable commercial sex between North American tourists and Latin American sex workers in San José, Costa Rica. I argue that understanding sex tourism necessitates looking at the relationships between various social groups rather than only between sex tourists and sex workers, in order to better understand the intense complexities of the encounters of transnational, transactional sex. 1 Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 2011, 10 (3), 392-411 393 Introduction The men in Costa Rica, they’re very macho, and the women just don’t like the men here. -

New European Honeymoon Destinations from Scott Dunn Scott Dunn Introduces Iceland, Sicily, Croatia and Montenegro for 2012

New European Honeymoon Destinations from Scott Dunn Scott Dunn Introduces Iceland, Sicily, Croatia and Montenegro for 2012 From Northern Light Safaris in Iceland, staying on an iconic island in Montenegro to snorkelling in the volcanic Aeolian Islands, luxury travel specialists, Scott Dunn have introduced a new collection of European honeymoon destinations for 2012. James Ferguson, Head of Scott Dunn’s European Escapes team commented, “Over the past year, we have definitely seen a trend for couples looking for honeymoons a little closer to home but with a twist. Guests are looking for an itinerary that is a little different and out of the ordinary, without compromising on style and romance – with just a hint of adventure.” Written in the stars: New Northern Lights Safari in Iceland Scientists predict that the magical Northern Lights will be at their brightest since 1958 this winter and coming spring. Couples looking to catch a glimpse of the elusive Aurora Borealis can now visit Iceland, the only destination where the lights can be witnessed throughout the whole country, with Scott Dunn’s new Northern Lights Safari - perfect for a winter honeymoon. After a romantic dip and in-water massage at the famous Blue Lagoon, honeymooners will explore the dramatic south coast from the chic art deco Hotel Borg in Reykjavik, Iceland’s quirky capital. By day, discover the natural wonders of the Golden Circle on an exhilarating private super jeep adventure. The more adventurous can continue to the Langjökull or Mýrdalsjökull glaciers to snowmobile across the icy, winter wonderland. Then as night falls, head out with a private driver and expert guide to seek the elusive Northern Lights. -

Hotel & Restaurant Management

Hotel & Restaurant The staff members in the Academic Student Services Office at the UC assist all students in Management determining which program of study to pursue. This includes providing information about the The Conrad N. Hilton College ranks among the variety of programs available, reviewing transcripts Hotel & world’s premier hotel and restaurant management to aid in identifying any courses to be completed programs. As the economy continues to be more before entering the program of choice, and serving service-oriented, the challenges and opportunities as liaison between the student and university of the hospitality industry demands the best from a program representatives. Students who have Restaurant new generation. The legendary Conrad N. Hilton’s already earned an associate’s degree or have a confidence in and vision for the University of substantial number of college academic credit Houston makes the future even brighter. hours should contact the Academic Student Services Office for advising and to begin the Management Houston’s restaurants, hotels and clubs feature a transfer admission process for the university variety of facilities and cuisines. Thus, work in, offering the degree program they desire to pursue. and interaction opportunities with, the hospitality industry are impressive. This sophisticated This brochure was created by the Academic environment, in addition to enriching the students’ Student Services Office based on information from learning process, provides direct and substantial the partner university. Bachelor of support to the Conrad N. Hilton College hospitality management program. LSCS and the partner universities provide equal employment, admission, and educational opportunities without regard to race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age or disability. -

2017 Midwinter Reports Reports Are Presented Exactly As Written

January 15, 2017 Subject: 2017 Midwinter Reports Reports are presented exactly as written by maker. Only reports submitted or forwarded to the Secretary Treasurer are included. Clicking on bookmarks in left column will take you directly to that report. Paul Kuntzmann, Secretary / Treasurer MEETING SCHEDULE MIDWINTER 2017 FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 17: OPEN MEETINGS IN THE CLUBHOUSE. FIELD TRIP TO THE AANR OFFICE CALL TO ORDER, MIDWINTER MEETING RECESS TO EXECUTIVE SESSION RECEPTION IN THE TERRACE SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 18: MIDWINTER TRUSTEE MEETING CONTINUES AANR EDUCATION FOUNDATION MEETING Presentation Schedule* Friday, February 17 TIME** ITEM PRESENTER 9:00 AM Call to Order President Bev Price 9:00 AM Panel Discussion on International Naturist Stephane Deschenes/ Dean Federation Hadley/ Barbara Hadley 9:45 AM Membership/Public Relations Dan Whicker/Melissa Sigman 10:30 AM Brainstorm Connett Fund Use President Bev Price 11:00 AM Florida Economic Impact Study Trustee, Ralph Collinson 11:15 AM Break/Dress in Business Casual 11:30 AM Depart for AANR Office Those with cars will transport 12:30 AM Ribbon Cutting and Rededication of Office Kissimmee C of C/others 1:30 PM Back to the Cove 2:00 PM Ad Hoc Membership Issues Committee Chair, Theresa “T” Price 3:00 PM Budget Chair, Bob Campbell 3:30 PM Break 3:45 PM Call to order, Midwinter Meeting (see agenda) President Bev Price 6:00 PM Reception in the Terrace Hosted by the Cove Schedule* Saturday, February 18 TIME** ITEM PRESENTER 9:00 AM Reconvene Midwinter Meeting (See Agenda) President, Bev Price 2:00 PM AANR Education Foundation, Clubhouse Gary Spangler TBD Group Dinner at Lakeside Carolyn Hawkins *Subject to change. -

BS with a Major in Hotel and Restaurant Management

Bachelor of Science This school offers the Bachelor of Science degree with majors in home furnishings merchandising, hotel and restaurant management, and merchandising. The following requirements must be satisfied for a Bachelor of Science. 1. Hours for the Degree: A minimum of 124 or 132 semester hours, depending upon major. 2. General University Requirements: See “General University Requirements” and “University Core Curriculum Requirements” in the Academics section of this catalog, and “Core Requirements” in this section of the catalog. 3. Major Requirements: See individual degree program. 4. Area of Concentration: See individual degree program. 5. Minor: See individual degree program. 6. Electives: See individual degree program. 7. Other Course Requirements: See individual degree program. 8. Other Requirements: • 42 hours must be advanced. • 24 of the last 30 must be taken at UNT. Hotel and Restaurant Management The hotel and restaurant management program prepares qualified individuals for managerial positions in the hospitality industry, and contributes to the profession through research, publication, consulting and related service activities. Major in Hotel and Restaurant Management Following is one suggested four-year degree plan. Students are encouraged to see their adviser each semester for help with program decisions and enrollment. BS with a Major in Hotel and Restaurant Management FRESHMAN YEAR FRESHMAN YEAR FALL HOURS SPRING HOURS ECON 1100, Principles of Microeconomics 3 ECON 1110, Principles of Macroeconomics 3 3 ENGL 1310,