Savannah River Basin REMAP Interim Report: Large Lake Embayments”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watershed Organizations in the Southeast Handout Watershed Organizations in the Southeast Handout

E | Attachment E: in the Organizations Watershed Southeast Handout Southeast Watershed Organizations in the Southeast Handout • Lake Lanier Handout - Alternative Nutrient Strategies Brown and Caldwell Alternative Nutrient Strategies This brochure provides information on watershed based collaboration for protecting and enhancing water quality and quantity. Examples from the southeastern United States are presented to show possibilities for further cooperation in the Lake Lanier watershed. Lake Lanier is a vital resource for its immediate restore compliance. These plans may be called neighbors and beyond, including portions of Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs). The plans Georgia, Florida, and Alabama. Lake Lanier may be developed with the use of models and provides water supply and multiple recreation may impose limitations on point sources and/or opportunities including boating and fishing. nonpoint sources. Protecting the lake is important to all stakeholders, especially now regarding nutrients. Since before the lake was created in the 1950s, stakeholders have worked to protect the lake Since the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, through water conservation, sophisticated the water quality and biological health of thousands wastewater treatment, stormwater management, of waterbodies have been evaluated. State and/or river cleanup events, and other efforts. As growth federal environmental agencies set a water use continues in the watershed, additional efforts will be classification for each waterbody, such as fishing, necessary to -

0306010606 Augusta Canal-Savannah River HUC 8 Watershed: Middle Savannah

Georgia Ecological Services U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 2/9/2021 HUC 10 Watershed Report HUC 10 Watershed: 0306010606 Augusta Canal-Savannah River HUC 8 Watershed: Middle Savannah Counties: Burke, Columbia, Richmond Major Waterbodies (in GA): McBean Creek, Savannah River, Butler Creek, Boggy Gut Creek, Reed Creek, Newberry Creek, Rocky Creek, Phinizy Swamp, Fort Gordon Reservoir, Bennock Millpond, Lake Olmstead, Millers Pond Federal Listed Species: (historic, known occurrence, or likely to occur in the watershed) E - Endangered, T - Threatened, C - Candidate, CCA - Candidate Conservation species, PE - Proposed Endangered, PT - Proposed Threatened, Pet - Petitioned, R - Rare, U - Uncommon, SC - Species of Concern. Shortnose Sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum) US: E; GA: E Occurrence; Please coordinate with National Marine Fisheries Service. Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus) US: E; GA: E Occurrence; Please coordinate with National Marine Fisheries Service. Wood Stork (Mycteria americana) US: T; GA: E Potential Range (county); Survey period: early May Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides borealis) US: E; GA: E Occurrence; Survey period: habitat any time of year or foraging individuals: 1 Apr - 31 May. Frosted Flatwoods Salamander (Ambystoma cingulatum) US: T; GA: T Potential Range (county); Survey period: for larvae 15 Feb - 15 Mar. Canby's Dropwort (Oxypolis canbyi) US: E; GA: E Potential Range (soil type); Survey period: for larvae 15 Feb - 15 Mar. Relict Trillium (Trillium reliquum) US: E; GA: E Occurrence; Survey period: flowering 15 Mar - 30 Apr. Use of a nearby reference site to more accurately determine local flowering period is recommended. Updated: 2/9/2021 0306010606 Augusta Canal-Savannah River 1 Georgia Ecological Services U.S. -

Like No Place on Earth

Like no Place on Earth Heaven’s Landing, the Middle of EVERYWHERE! - Mike Ciochetti EVERYWHERE Heaven’s Landing is a residential fly-in community located in the Blue Ridge Mountains of northeast Georgia. Immediately surrounded by the pristine EVERYTHING serenity of the Chattahoochee National Forest, one could easily get the impression that Heaven’s Landing is located in the middle of nowhere. After all, virtually every photograph that you see of Heaven’s Landing shows a 5,200 The Races foot runway surrounded by colorful mountain wilderness. To the contrary, however, Heaven’s Landing is only 3.5 miles from the City of Clayton, Georgia, and very much in the middle of EVERYWHERE! Fall Sweeps A seven-minute drive from Heaven’s Landing brings you to downtown Clayton, which has the best of just about EVERYTHING! Four of the top 100 rated Where to Find Us chefs in the U.S. operate restaurants in Rabun County to the delight of gourmet foodies. Rabun County was named the “Farm to Table Capital of Georgia!” This is a testament to the great relationships the chefs have with the Circus Arts local farms, following the practices of the finest eateries, and the abundant availability of farm fresh organic meats and produce. If you don’t care to dine out, shoppers will delight in the finest supermarkets, farmer’s markets, Mark Your organic food co-op’s and old fashioned local butcher shops that you will find Calendar ANYWHERE! So Heaven’s Landing has your fine dining needs covered, what is there to do Events to work up an appetite? Once again the answer is EVERYTHING! Let’s start with Lake Burton, a renowned 2,735 acre crystal clear mountain lake where Concierge you can water ski, jet ski, fish, or just cruise on your boat and sunbathe in an atmosphere that is pure nirvana. -

About Savannah River National Laboratory

SRNL is a DOE National Laboratory operated by Savannah River Nuclear Solutions. about Savannah River National Laboratory U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY • SAVANNAH RIVER SITE • AIKEN • SC srnl.doe.gov SRNL Fast Facts Intelligence and Nonproliferation Assessments Located at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site at Savannah River National Laboratory near Aiken, South Carolina The Savannah River National Laboratory (SRNL) has extensive experience in supporting the intelligence needs of Operated by the United States and provides a conduit for making SRNL’s Savannah River Nuclear Solutions technical capabilities available to the U.S. intelligence community. SRNL’s internationally recognized expertise “National Laboratory” for DOE stems from the Savannah River Site’s (SRS) rich history of Office of Environmental Management missions supporting the nation’s nuclear weapons stockpile. SRS has a broad base of expertise to include nuclear Applied research, development and reactor operations, plutonium and tritium processing, spent deployment of practical, high-value nuclear fuel reprocessing, environmental monitoring, and and cost effect technology solutions materials science. This experience and knowledge driven in the areas of national security, clean environment allows SRNL to be a valuable resource in U.S. energy and environmental stewardship intelligence and nonproliferation efforts. SRNL Analysis Focus Areas Supporting customers at SRS, DOE and other federal agencies • Foreign Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) Program nationally and internationally • Nuclear Fuel Cycle Facilities - Nuclear reactors, heavy water facilities, reprocessing plants, tritium production Contact Information - Materials security SRNL Office of Communications 803.725.4396 • Remote Sensing • Nonproliferation Policy - Treaties, agreements and regimes - Export control and licensing SRNL supports the arms control and nonproliferation efforts of the U.S. -

Rights of Way Endangered Species Survey for the Northeast Region of Georgia

RIGHTS OF WAY ENDANGERED SPECIES SURVEY FOR THE NORTHEAST REGION OF GEORGIA. The Northeast Region ofGeorgia includes 24 counties: Banks, Barrows, Clarke, Dawson, Elbert, Fannin, Forsyth, Franklin, Greene, Habersham, Hart, Hall, Jackson, Lumpkin, Madison, Morgan, Oconee, Oglethorpe, Rabun, Stephens, Towns, Union, Walton and White. Based on The Georgia Natural Heritage Inventory records, the following plants and plant community locations were searched for on Georgia Power Company rights ofways: Georgia aster - Aster georgianus Dwarfstonecrop - Sedum pusillum Indian olive - Nestronia umbellulua Silky bindweed - Calystegia catesbiana ssp. sericata Smooth purple coneflower - Echinacea laevigata (Federal Endangered) Ginseng - Panax quinquefolius Pipewort - Eriocaulon koemickianum American Milkwort - Pilularia Americana Granite outcrop (shrub, bare rock, lichen) communities There are three maintenance concerns. Two are minor concerns in Walton county with granite outcrops communities. (See Walton county summary) and one in Stephens county with smooth purnle coneflower (See Stephens county summary). Discussion and recommendations: A few ofthe Northeast Region counties are located in the mountains and foothill region ofGeorgia, but most are in the Piedmont. Much of the Georgia mountain region is owned and managed by the United States Forest Service. Georgia Power has large holdings in this area as well and has been involved with protected species (persistent trillium Trillium persistents and the green salamander aneides aeneus) on company lands at Tallulah Gorge, but these species locations are not close to Georgia Power rights ofways so there are no concerns for right ofway maintenance. The majority oflocations in this region, are within the Piedmont province. Due to a long history ofearly European use (and misuse) for settlement, agriculture and logging, the original Piedmont plant communities ofGeorgia have been altered drastically over the past 2 centuries. -

Streamflow Maps of Georgia's Major Rivers

GEORGIA STATE DIVISION OF CONSERVATION DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINING AND GEOLOGY GARLAND PEYTON, Director THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Information Circular 21 STREAMFLOW MAPS OF GEORGIA'S MAJOR RIVERS by M. T. Thomson United States Geological Survey Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C. ATLANTA 1960 STREAMFLOW MAPS OF GEORGIA'S MAJOR RIVERS by M. T. Thomson Maps are commonly used to show the approximate rates of flow at all localities along the river systems. In addition to average flow, this collection of streamflow maps of Georgia's major rivers shows features such as low flows, flood flows, storage requirements, water power, the effects of storage reservoirs and power operations, and some comparisons of streamflows in different parts of the State. Most of the information shown on the streamflow maps was taken from "The Availability and use of Water in Georgia" by M. T. Thomson, S. M. Herrick, Eugene Brown, and others pub lished as Bulletin No. 65 in December 1956 by the Georgia Department of Mines, Mining and Geo logy. The average flows reported in that publication and sho\vn on these maps were for the years 1937-1955. That publication should be consulted for detailed information. More recent streamflow information may be obtained from the Atlanta District Office of the Surface Water Branch, Water Resources Division, U. S. Geological Survey, 805 Peachtree Street, N.E., Room 609, Atlanta 8, Georgia. In order to show the streamflows and other features clearly, the river locations are distorted slightly, their lengths are not to scale, and some features are shown by block-like patterns. -

The Savannah River System L STEVENS CR

The upper reaches of the Bald Eagle river cut through Tallulah Gorge. LAKE TOXAWAY MIDDLE FORK The Seneca and Tugaloo Rivers come together near Hartwell, Georgia CASHIERS SAPPHIRE 0AKLAND TOXAWAY R. to form the Savannah River. From that point, the Savannah flows 300 GRIMSHAWES miles southeasterly to the Atlantic Ocean. The Watershed ROCK BOTTOM A ridge of high ground borders Fly fishermen catch trout on the every river system. This ridge Chattooga and Tallulah Rivers, COLLECTING encloses what is called a EASTATOE CR. SATOLAH tributaries of the Savannah in SYSTEM watershed. Beyond the ridge, LAKE Northeast Georgia. all water flows into another river RABUN BALD SUNSET JOCASSEE JOCASSEE system. Just as water in a bowl flows downward to a common MOUNTAIN CITY destination, all rivers, creeks, KEOWEE RIVER streams, ponds, lakes, wetlands SALEM and other types of water bodies TALLULAH R. CLAYTON PICKENS TAMASSEE in a watershed drain into the MOUNTAIN REST WOLF CR. river system. A watershed creates LAKE BURTON TIGER STEKOA CR. a natural community where CHATTOOGA RIVER ARIAIL every living thing has something WHETSTONE TRANSPORTING WILEY EASLEY SYSTEM in common – the source and SEED LAKEMONT SIX MILE LAKE GOLDEN CR. final disposition of their water. LAKE RABUN LONG CREEK LIBERTY CATEECHEE TALLULAH CHAUGA R. WALHALLA LAKE Tributary Network FALLS KEOWEE NORRIS One of the most surprising characteristics TUGALOO WEST UNION SIXMILE CR. DISPERSING LAKE of a river system is the intricate tributary SYSTEM COURTENAY NEWRY CENTRALEIGHTEENMILE CR. network that makes up the collecting YONAH TWELVEMILE CR. system. This detail does not show the TURNERVILLE LAKE RICHLAND UTICA A River System entire network, only a tiny portion of it. -

GEORGIA TROUT FISHING REGULATIONS Trout Season Trout

GEORGIA TROUT FISHING REGULATIONS Trout Season All designated trout waters are now open year round. Trout Fishing Hours • Fishing 24 hours a day is allowed on all trout streams and all impoundments on trout streams except those in the next paragraph. • Fishing hours on Dockery Lake, Rock Creek Lake, the Chattahoochee River from Buford Dam to Peachtree Creek, the Conasauga River watershed upstream of the Georgia-Tennessee state line and Smith Creek downstream of Unicoi dam are 30 minutes before sunrise until 30 minutes after sunset. Night fishing is not allowed. Trout Fishing Rules • Trout anglers are restricted to the use of one pole and line which must be hand held. No other type of gear may be used in trout streams. • It is unlawful to use live fish for bait in trout streams. Seining bait-fish is not allowed in any trout stream. Impoundments On Trout Streams Anglers can: • Fish for fish species other than trout without a trout license on Dockery and Rock Creek lakes. • Fish at night, except on Dockery and Rock Creek lakes. See Trout Fishing Hours for details. Impoundment notes: • If you fish for or possess trout, you must possess a trout license. If you catch a trout and do not possess a trout license you must release the trout immediately. • State park visitors are not required to have a trout license to fish in the impounded waters of the Park. However, those visitors wishing to harvest trout will need to have a trout license in their possession. Delayed Harvest Streams Anglers fishing delayed harvest streams must release all trout immediately and use and possess only artificial lures with one single hook per lure from Nov. -

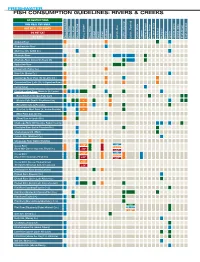

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. -

Savannah River Basin Management Plan 2001

Savannah River Basin Management Plan 2001 Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Georgia River Basin Management Planning Vision, Mission, and Goals What is the VISION for the Georgia RBMP Approach? Clean water to drink, clean water for aquatic life, and clean water for recreation, in adequate amounts to support all these uses in all river basins in the state of Georgia. What is the RBMP MISSION? To develop and implement a river basin planning program to protect, enhance, and restore the waters of the State of Georgia, that will provide for effective monitoring, allocation, use, regulation, and management of water resources. [Established January 1994 by a joint basin advisory committee workgroup.] What are the GOALS to Guide RBMP? 1) To meet or exceed local, state, and federal laws, rules, and regulations. And be consistent with other applicable plans. 2) To identify existing and future water quality issues, emphasizing nonpoint sources of pollution. 3) To propose water quality improvement practices encouraging local involvement to reduce pollution, and monitor and protect water quality. 4) To involve all interested citizens and appropriate organizations in plan development and implementation. 5) To coordinate with other river plans and regional planning. 6) To facilitate local, state, and federal activities to monitor and protect water quality. 7) To identify existing and potential water availability problems and to coordinate development of alternatives. 8) To provide for education of the general public on matters involving the environment and ecological concerns specific to each river basin. 9) To provide for improving aquatic habitat and exploring the feasibility of re-establishing native species of fish. -

Iron Sequestration in Lake Sediments from Artificial Hypolimnetic Oxygenation: Richard B. Russell Reservoir Amanda Elrod Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 12-2007 Iron sequestration in lake sediments from artificial hypolimnetic oxygenation: Richard B. Russell Reservoir Amanda Elrod Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons Recommended Citation Elrod, Amanda, "Iron sequestration in lake sediments from artificial hypolimnetic oxygenation: Richard B. Russell Reservoir" (2007). All Theses. 273. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRON SEQUESTRATION IN LAKE SEDIMENTS FROM ARTIFICIAL HYPOLIMNETIC OXYGENATION: RICHARD B. RUSSELL RESERVOIR A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Biological Sciences by Amanda Kathleen Elrod December 2007 Accepted by: Dr. John J. Hains, Committee Chair Dr. Steven Klaine Dr. Mark Schlautman ABSTRACT The Upper Savannah River watershed has numerous impoundments, and the three largest hydroelectric reservoirs, from north to south, are Hartwell, Richard B. Russell, and J. Strom Thurmond Lakes. During the summer months, these reservoirs undergo thermal and chemical stratification, which results in the formation of cool, hypoxic/anoxic hypolimnia and warm, oxic epilimnion. To maintain fisheries habitat, the United States Army Corps of Engineers operates a hypolimnetic oxygenation system in the forebay of Richard B. Russell Lake. The purpose of this system is to improve the water quality of the releases from Richard B. -

Savannah River Basin

WATERSHED CONDITIONS: SAVANNAH RIVER BASIN Broad Upper Savannah Lynches SANTEE Pee Dee Catawba- Saluda Wateree Little SA Pee Dee V ANN Congaree PEE DEE Waccamaw Black AH Santee Lower Edisto Savannah ACE Ashley- VIRGINI A Cooper Combahee- Coosawhatchie NO RT H C A R OLI NA Pee Dee Santee basin basin SOUTH Savannah CA RO LI NA basin ACE GEORGIA basin South Carolina Water Assessment 8-1 UPPER SAVANNAH RIVER SUBBASIN The region is predominantly rural, and its principal population centers are dispersed along its length. The major towns in 2000 were Anderson (25,514), Greenwood (22,071), Easley (17,754), Clemson (11,939), Seneca (7,652), and Abbeville (5,840). The year 2005 per capita income for the subbasin counties ranged from $20,643 in McCormick County, which ranked 40th in the State, to $28,561 in Oconee County, which ranked ninth. All of the counties in the subbasin had 1999 median household incomes below the State average of $37,082. Abbeville and McCormick Counties had median household incomes more than $4,000 below the State average (South Carolina Budget and Control Board, 2005). During 2000, the counties of the subbasin had combined annual average employment of non- agricultural wage and salary workers of about 216,000. Labor distribution within the subbasin counties included management, professional, and technical services, 26 percent; production, transportation, and materials moving, 25 percent; sales and office, 22 percent; service, UPPER SAVANNAH RIVER SUBBASIN 14 percent; construction, extraction, and maintenance, 13 percent; and farming, fishing, and forestry, 1 percent. The Upper Savannah River subbasin is located in northwestern South Carolina and extends 140 miles In the sector of manufacturing and public utilities, the southeast from the North Carolina state line to the 1997 annual product value for the subbasin’s counties was Edgefield-Aiken county line.