Professor Xavier Is a Gay Traitor! an Antiassimilationist Framework for Interpreting Ideology, Power and Statecraft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Lego Constructs a Cross-Promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2013 How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Wooten, David Robert, "How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2013 ABSTRACT HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Newman The purpose of this project is to examine how the cross-promotional Lego video game series functions as the site of a complex relationship between a major toy manufacturer and several media conglomerates simultaneously to create this series of licensed texts. The Lego video game series is financially successful outselling traditionally produced licensed video games. The Lego series also receives critical acclaim from both gaming magazine reviews and user reviews. By conducting both an industrial and audience address study, this project displays how texts that begin as promotional products for Hollywood movies and a toy line can grow into their own franchise of releases that stills bolster the original work. -

Blade II" (Luke Goss), the Reapers Feed Quickly

J.antie Lissow- knocks Starbucks, offers funny anecdotes By Jessica Besack has been steadily rising. stuff. If you take out a whole said, you might find "Daddy's bright !)ink T -shirt with the Staff Writer He is now signed under the shelf, it will only cost you $20." Little Princess" upon closer sparkly words "Daddy's Little Gersh Agency, which handles Starbucks' coffee was another reading. Princess" emblazoned across the Comedian Jamie Lissow other comics such as Dave object of Lissow's humor. He In conclusion to his routine, front. entertained a small audience in Chappele, Jim Breuer and The warned the audience to be cau Lissow removed his hooded You can read more about the Wolves' Den this past Friday Kids in the Hall. tious when ordering coffee there, sweatshirt to reveal a muscular Jamie Lissow at evening joking about Starbucks Lissow amused the audience since he has experienced torso bulging out of a tight, http://www.jamielissow.com. coffee, workout buffs, dollar with anecdotes of his experi mishaps in the process. stores and The University itself. ences while touring other col "I once asked 'Could I get a Lissow, who has appeared on leges during the past few weeks. triple caramel frappuccino "The Tonight Show with Jay At one college, he performed pocus-mocha?"' Lissow said, Leno" and NBC's "Late Friday," on a stage with no microphone "and the coffee lady turned into a opened his act with a comment after an awkward introduction, newt. I think I said it wrong." about the size of the audience, only to notice that halfway Lissow asked audience what saying that when he booked The through his act, students began the popular bars were for University show, he presented approaching the stage carrying University students. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

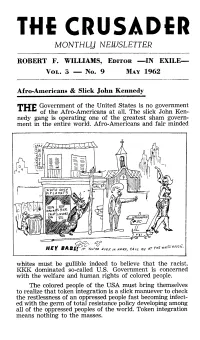

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

Super Ticket Student Edition.Pdf

THE NATION’S NEWSPAPER Math TODAY™ Student Edition Super Ticket Sales Focus Questions: h What are the values of the mean, median, and mode for opening weekend ticket sales and total ticket sales of this group of Super ticket sales movies? Marvel Studio’s Avi Arad is on a hot streak, having pro- duced six consecutive No. 1 hits at the box office. h For each data set, determine the difference between the mean and Blade (1998) median values. Opening Total ticket $17.1 $70.1 weekend sales X-Men (2000) (in millions) h How do opening weekend ticket $54.5 $157.3 sales compare as a percent of Blade 2 (2002) total ticket sales? $32.5 $81.7 Spider-Man (2002) $114.8 $403.7 Daredevil (2003) $45 $102.2 X2: X-Men United (2003) 1 $85.6 $200.3 1 – Still in theaters Source: Nielsen EDI By Julie Snider, USA TODAY Activity Overview: In this activity, you will create two box and whisker plots of the data in the USA TODAY Snapshot® "Super ticket sales." You will calculate mean, median and mode values for both sets of data. You will then compare the two sets of data by analyzing the differences graphically in the box and whisker plots, and numerically as percents of ticket sales. ©COPYRIGHT 2004 USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co., Inc. This activity was created for use with Texas Instruments handheld technology. MATH TODAY STUDENT EDITION Super Ticket Sales Conquering comic heroes LIFE SECTION - FRIDAY - APRIL 26, 2002 - PAGE 1D By Susan Wloszczyna USA TODAY Behind nearly every timeless comic- Man comic books the way an English generations weaned on cowls and book hero, there's a deceptively unas- scholar loves Macbeth," he confess- capes. -

Sam Urdank, Resume JULY

SAM URDANK Photographer 310- 877- 8319 www.samurdank.com BAD WORDS DIRECTOR: Jason Bateman CAST: Jason Bateman, Kathryn Hahn, Rohan Chand, Philip Baker Hall INDEPENDENT FILM Allison Janney, Ben Falcone, Steve Witting COFFEE TOWN DIRECTOR: Brad Campbell INDEPENDENT FILM CAST: Glenn Howerton, Steve Little, Ben Schwartz, Josh Groban Adrianne Palicki TAKEN 2 DIRECTOR: Olivier Megato TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (L.A. 1st Unit) CAST: Liam Neeson, Maggie Grace,,Famke Janssen, THE APPARITION DIRECTOR: Todd Lincoln WARNER BRO. PICTURES (L.A. 1st Unit) CAST: Ashley Greene, Sebastian Stan, Tom Felton SYMPATHY FOR DELICIOUS DIRECTOR: Mark Ruffalo CORNER STORE ENTERTAINMENT CAST: Christopher Thornton, Mark Ruffalo, Juliette Lewis, Laura Linney, Orlando Bloom, Noah Emmerich, James Karen, John Caroll Lynch EXTRACT DIRECTOR: Mike Judge MIRAMAX FILMS CAST: Jason Bateman, Mila Kunis, Kristen Wiig, Ben Affleck, JK Simmons, Clifton Curtis THE INVENTION OF LYING DIRECTOR: Ricky Gervais & Matt Robinson WARNER BROS. PICTURES CAST: Ricky Gervais, Jennifer Garner, Rob Lowe, Lewis C.K., Tina Fey, Jeffrey Tambor Jonah Hill, Jason Batemann, Philip Seymore Hoffman, Edward Norton ROLE MODELS DIRECTOR: David Wain UNIVERSAL PICTURES CAST: Seann William Scott, Paul Rudd, Jane Lynch, Christopher Mintz-Plasse Bobb’e J. Thompson, Elizabeth Banks WITLESS PROTECTION DIRECTOR: Charles Robert Carner LIONSGATE CAST: Larry the Cable Guy, Ivana Milicevic, Yaphet Kotto, Peter Stomare, Jenny McCarthy, Joe Montegna, Eric Roberts DAYS OF WRATH DIRECTOR: Celia Fox FOXY FILMS/INDEPENDENT -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Beaumont Art League Summer Activities

A View From The Top Greg Busceme, TASI Director THIS IS OUR SUMMER ISSUE which is fol- 50 organizations receive a $1,000 grant. lowed by two months of limited communi- We are grateful for The Stark cation by mail or print. Foundation’s contribution to The Art This is partially by design and partial- Studio. The funds will go to rebuilding our ly by necessity to give us a chance to security fence around the Studio yard and recover from our printing and mailing improving our parking arrangements — Vol. 17, No. 9 ISSUE costs for monthly invitations and newspa- an integral part of an ongoing project to pers. Printing costs alone average about revitalize our facility as we recover fully Publisher . The Art Studio, Inc. $580 a month. from the storms. We already have part- Editor . Andy Coughlan This is not just to whine but to let ners in this project beginning with Boy Copy Editor . Tracy Danna everyone know we are getting serious Scout Eagle candidate Brandon Cate. In Contributing Writers . Elena Ivanova about membership renewals and new pursuit of being an Eagle Scout, Brandon Distribution Volunteer . Elizabeth Pearson members. For the first time, we can only has taken on the task of striping our new send exhibition announcements and parking area for improved space and a The Art Studio, Inc. Board of Directors ISSUE to members in good standing. safer environment. On our part, we will We hope those non-members who use the Stark funds to get the material President Ex-Officio . Greg Busceme have been enjoying our mailings remem- necessary to put up a fence on the front of Vice-President. -

CITIZEN #162 Catalogue.Indd

Bien le bonjour à toutes et à tous ! Je ne sais plus vraiment qui a eu la géniale idée d’inventer les vacances et autres congés, mais, sur ce coup-là, il m’a vraiment mis dans la panade.., ce n’est plus de édito retard c’est carrément pire que tout bref, je vais la faire courte ce mois afi n de transmettre le plus rapidement possible l’opus 162 du Citizen à mon imprimeur préféré : j’ai nommé François C. de chez Print Forum à Wasquehal ! Ne me reste qu’à faire un coucou à Sébastien B. de Clamart ! il se reconnaîtra... je tiens avant tout à le remercier de sa fi délité. oups c’est fait et c’est tout pour aujourd’hui! à plus et merci pour votre fi délité !!! L’équipe d’Astro (Damien, Fred & Jérôme) PS : je ne résiste pas à vous faire mon habituel petit rappel pour les titres VF ou encore VO : si vous êtes tenté par l’une ou l’autre des séries récentes mais n’osez vous lancer de peur de ne jamais récupérer les numéros et volumes précédents, n’ayez crainte et … demandez ! La plupart du temps il nous est encore possible, voire faisable, de réassortir un numéro ou plusieurs alors, lancez-vous ! news de JUIN 2015 news la cover du mois : JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA #1 par Bryan Hitch Le logo astrocity et la super-heroïne Un peu de lexique... “astrogirl” ont été créés par Blackface. Corp et sont la propriété exclusive de Damien GN pour Graphic novel : La traduction littérale de ce terme est «roman graphique» Rameaux & Frédéric Dufl ot au titre de la OS pour One shot : Histoire en un épisode, publié le plus souvent à part de la continuité régulière. -

Marvel-Phile: Über-Grim-And-Gritty EXTREME Edition!

10 MAR 2018 1 Marvel-Phile: Über-Grim-and-Gritty EXTREME Edition! It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It 90s, but you’d be wrong. Then we have Nightwatch, a was a dark time for the Republic. In short, it was...the bald-faced ripoff of Todd MacFarlane’s more ‘90s. The 1990s were an odd time for comic books. A successful Spawn. Next, we have Necromancer… the group of comic book artists, including the likes of Jim Dr. Strange of Counter-Earth. And best for last, Lee and hate-favorite Rob Liefield, splintered off from there’s Adam X the X-TREME! Oh dear Lord -- is there Marvel Comics to start their own little company called anything more 90s than this guy? With his backwards Image. True to its name, Image Comics featured comic baseball cap, combustible blood, a costume seemingly books light on story, heavy on big, flashy art (often made of blades, and a title that features not one but either badly drawn or heavily stylized, depending on TWO “X”s, this guy that was teased as the (thankfully who you ask), and a grim and gritty aesthetic that retconned) “third Summers brother” is literally seemed to take all the wrong lessons from renowned everything about the 90s in comics, all rolled into one. works such as Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns. Don’t get me wrong, there were a few gems in the It wasn’t long until the Big Two and other publishers 1990s. Some of my favorite indie books were made hopped on the bandwagon, which was fueled by during that time. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Resistant Vulnerability in the Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 2-15-2019 1:00 PM Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America Kristen Allison The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Susan Knabe The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Kristen Allison 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Allison, Kristen, "Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6086. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6086 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Established in 2008 with the release of Iron Man, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become a ubiquitous transmedia sensation. Its uniquely interwoven narrative provides auspicious grounds for scholarly consideration. The franchise conscientiously presents larger-than-life superheroes as complex and incredibly emotional individuals who form profound interpersonal relationships with one another. This thesis explores Sarah Hagelin’s concept of resistant vulnerability, which she defines as a “shared human experience,” as it manifests in the substantial relationships that Steve Rogers (Captain America) cultivates throughout the Captain America narrative (11). This project focuses on Steve’s relationships with the following characters: Agent Peggy Carter, Natasha Romanoff (Black Widow), and Bucky Barnes (The Winter Soldier).