The Chase Through Time: Archival Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talbot Street/Lichfield Street, Rugeley CA Appraisal 2019

Talbot Street/Lichfield Street, Rugeley Conservation Area Appraisal 2019 Search for ‘Cannock Chase Life’ @CannockChaseDC www.cannockchasedc.gov.uk Conservation Area Appraisal Talbot Street/Lichfield Street, Rugeley 1. Introduction A Conservation Area is “an area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance”. The Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 places a duty on the local authority to designate Conservation Areas where appropriate. It also requires the local authority to formulate and publish proposals for the preservation or enhancement of these areas. An Appraisal was first produced for Talbot Street/Lichfield Street Conservation Area in 2005 and this document updates its predecessor making use of much of the information contained therein. The updates comprise some rearrangement of layout to accord with the house style developed subsequently, updates to the planning policy context following national and local policy changes, and references reflecting recent development and changes of use in the Conservation Area. This Appraisal seeks to provide a clear definition of the special architectural or historic interest that warranted designation of Talbot Street/Lichfield Street as a Conservation Area through a written appraisal of its character and appearance – what matters and why. The Appraisal is intended as a guide upon which to base the form and style of future development in the area. It is supported by adopted policy in Cannock Chase Local Plan (Part 1) 2014 CP15 seeking to protect and enhance the historic environment, policies CP12 and CP14 aiming to conserve biodiversity and landscape character and Policy CP3 seeking high standards of design. -

Lichfield Community Safety Delivery Plan

Lichfield District Community Safety Delivery Plan 2017 - 2020 Foreword Our aim is to ensure that Lichfield District remains one of the safest places in the county and this Delivery Plan will provide the means by which the community safety priorities highlighted in the 2016 Strategic Assessment can be delivered. Members of our Safer Community Partnership will lead on the delivery of our priority actions, but we cannot make this happen on our own. We hope that partners, stakeholders, local people and communities will take responsibility, demonstrate commitment and make a real contribution to help realise our vision for a safe District. The Partnership has embraced a number of changes over recent years, not least the challenges brought about by the current financial pressures experienced by all public sector organisations. Difficult decisions are having to be made which impact on people's quality of life, so it's important we utilise what funding we do have effectively. Other challenges we need to be mindful of are national and international terrorism and violence which has had a high media profile over recent times, together with the extent of child sexual exploitation (CSE) and Modern Day Slavery (MDS) within our communities. Much more emphasis is being placed on identifying and supporting people, especially young people and children, who are vulnerable to any form of exploitation and radicalisation. The opportunities and threats of social media have also become a major consideration going forward as we need to support local residents, especially young people to use it safely. Community safety is a complex and challenging area of work and we are grateful for the support and enthusiasm of all who are driven to continually improve the quality of life for people who live in the District. -

Old Heath Hayes' Have Been Loaned 1'Rom Many Aources Private Collections, Treasured Albums and Local Authority Archives

OLD HEATH HAVES STAFFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL. EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, LOCAL HISTORY SOURCE BOOK L.50 OLD HEATH HAVES BY J.B. BUCKNALL AND J,R, FRANCIS MARQU£SS OF' ANGl.ESEV. LORO OF' THE MAtt0R OF HEATH HAVES STAFFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL, EDUCATION DEPAR TMENT. IN APPRECIATION It is with regret that this booklet will be the last venture produced by the Staffordshire Authority under the inspiration and guidance of Mr. R.A. Lewis, as historical resource material for schools. Publi cation of the volume coincides with the retirement of Roy Lewis, a former Headteacher of Lydney School, Gloucestershire, after some 21 years of service in the Authority as County Inspector for History. When it was first known that he was thinking of a cessation of his Staffordshire duties, a quick count was made of our piles of his 'source books' . Our stock of his well known 'Green Books' (Local History Source Books) and 'Blue Books' (Teachers Guides and Study Books) totalled, amazingly, just over 100 volumes, ·a mountain of his torical source material ' made available for use within our schools - a notable achievement. Stimulating, authoritative and challenging, they have outlined our local historical heritage in clear and concise form, and have brought the local history of Staffordshire to the prominence that it justly deserves. These volumes have either been written by him or employed the willing ly volunteered services of Staffordshire teachers. Whatever the agency behind the pen it is obvious that forward planning, correlation of text and pictorial aspects, financial considerations for production runs, organisation of print-run time with a busy print room, distri bution of booklets throughout Staffordshire schools etc. -

47 Little Tixall Lane

Little Tixall Lane Great Haywood, Stafford, ST18 0SE Little Tixall Lane Great Haywood, Stafford, ST18 0SE A deceptively spacious family sized detached chalet style bungalow, occupying a very pleasant position within the sought after village of Great Haywood. Reception Hall with Sitting Area, Cloakroom, Lounge, Breakfast Kitchen, Utility, Conservatory, Dining Room, En Suite Bedroom, First Floor: Three Bedrooms, Bathroom Outside: Front and Rear Gardens, Drive to Garage Guide Price £300,000 Accommodation Reception Hall with Sitting Area having a front entrance door and built in cloaks cupboards. There is a Guest Cloakroom off with white suite comprising low flush w.c and wash basin. Spacious Lounge with two front facing windows to lawned front garden and a Regency style fire surround with coal effect fire, tiled hearth and inset. The Breakfast Kitchen has a range of high and low level units with work surfaces and a sink and drainer. Rangemaster range style oven with extractor canopy over. Off the kitchen is a Utility with space and provision for domestic appliances and the room also houses the wall mounted gas boiler. Conservatory having double French style doors to the side and a separate Dining Room with double doors opening from the kitchen, French style doors to the garden and stairs rising to the first floor. Bedroom with fitted bedroom furniture, double French style doors opening to the garden and access to the En Suite which has a double width shower, pedestal wash basin and low flush w.c. First Floor There are Three Bedrooms, all of which have restricted roof height in some areas, and also to part of the Bathroom which comprises bath, pedestal wash basin and low flush w.c. -

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation Proposals for a new pattern of divisions Produced by Peter McKenzie, Richard Cressey and Mark Sproston Contents 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 2 Approach to Developing Proposals.........................................................................1 3 Summary of Proposals .............................................................................................2 4 Cannock Chase District Council Area .....................................................................4 5 East Staffordshire Borough Council area ...............................................................9 6 Lichfield District Council Area ...............................................................................14 7 Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Area ....................................................18 8 South Staffordshire District Council Area.............................................................25 9 Stafford Borough Council Area..............................................................................31 10 Staffordshire Moorlands District Council Area.....................................................38 11 Tamworth Borough Council Area...........................................................................41 12 Conclusions.............................................................................................................45 -

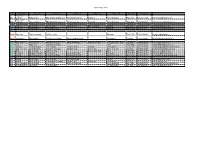

Planning Weekly List

1 STAFFORD BOROUGH COUNCIL - ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND PLANNING LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS – WEEK ENDING 13 AUGUST 2021 View planning applications via Public Access Heading Application Information Applicant/Agent Proposal and Location Type of Application APP NO 21/34087/HOU Mr K Hazel Side extension to provide Householder C/O J T Design lounge and increase size Jessica Allsopp VALID 9 August 2021 Partnership LLP of porch with tiled roof. FAO Mr G Deffley Map Reference: PARISH Stone Town The Cart Hovel 192 Lichfield Road E:391573 Court Drive Stone N:332712 WARD St Michaels And Stonefield Shenstone ST15 8PY Lichfield UPRN 100031794309 WS14 0JQ APP NO 21/34116/HOU Mr Paul Oxley Demolition of existing Householder Hillside single storey double Jodie Harris VALID 28 July 2021 Billington Bank wooden garage with a Haughton store and replacement with Map Reference: PARISH Bradley Stafford a similar two storey E:388273 ST18 9DJ garage, the additional N:320534 WARD Seighford And Church storey being extra storage Eaton and a games room. UPRN 200001329272 Hillside Billington Bank Billington APP NO 21/34545/HOU Ms V Pendleton Proposed two storey Householder C/O Mr J Payne extension to side of Mr S Owen VALID 23 July 2021 10 Dilhorne Road existing semi detached Forsbrook dwelling to provide two Map Reference: PARISH Fulford Stoke On Trent additional bedrooms & E:394377 ST11 9DJ bathroom on first floor, N:341638 WARD Fulford additional kitchen/ dining room to ground floor UPRN 100031788254 8 Ash Grove Blythe Bridge Stoke On Trent APP NO 21/34240/HOU Mr G Hurlstone Proposed two storey side Householder C/O Blakeman Building extension. -

The Cannock Chase Geotrail

CCGCOVER10.3.09.indd 1 CCGCOVER10.3.09.indd 10/3/09 17:53:43 10/3/09 Not to scale to Not Unconformity Fault Fault Hopwood Hopwood Fault Tixall Tixall Boundary Boundary Basin Basin Cannock Chase Cannock Cover Photograph: Source of the Sher Brook Sher the of Source Photograph: Cover 370080 01782 Tel: Services Print MC by Printed Eastern Eastern Needwood Needwood Stafford warnings EAST WEST consider other people. Please adhere to all Forestry Commission instructions and and instructions Commission Forestry all to adhere Please people. other consider protect plants and animals and take your litter home. Keep dogs under control and and control under dogs Keep home. litter your take and animals and plants protect Not to scale to Not safe, plan ahead and follow any signs; leave gates and property as you find them; them; find you as property and gates leave signs; any follow and ahead plan safe, Remember to follow the country code and please do not hammer rock surfaces. Be Be surfaces. rock hammer not do please and code country the follow to Remember www.staffs-wildlife.org.uk Staffordshire Wildlife Trust – – Trust Wildlife Staffordshire www.esci.keele.ac.uk/nsgga North Staffordshire Group Geologists’ Association – – Association Geologists’ Group Staffordshire North Unconformity Valley www.staffs-rigs.org.uk Staffordshire RIGS – RIGS Staffordshire Trent Little Haywood Little phological sites in Staffordshire. For more information contact: information more For Staffordshire. in sites phological Old Park Old Cannock Chase Cannock Beaudesert Beaudesert -

Dentalroots Issue 3 2012 the Dentistry Alumni Magazine

DentalROOTS Issue 3 2012 The Dentistry alumni magazine The war against gum disease Also inside: Dentistry’s new home on track for 2014; Community dental expert recalls life in the Firm 2 DentalROOTS Fruit and vegetable compound offers hope against gum disease Scientists at the University of Birmingham have found that supplementing the diet with a special Welcome combination of fruit and vegetable juice powder concentrates may Welcome to the 2012 edition of DentalROOTS, our annual publication intended to keep alumni help to combat chronic gum disease informed on developments in the School of Dentistry during the past year. when combined with conventional dental therapy. We continue to take a forward-looking approach to provide our students with a distinctive high-quality experience. Our students stand tall with no side lean, given the end of the student The results of a preliminary randomised cabinets and also their performance in the national recruitment process and finals. This year saw controlled study show that taking a daily the introduction of a new national recruitment system for foundation training. Any change can be dose of capsules containing concentrated stressful and one such as this even more so given the potential for having a profound impact on phytonutrients improved clinical outcomes the graduates, future careers. The 2012 Birmingham final year students fared well, all passed for patients with chronic periodontitis finals and all were offered a foundation training place; a fortunate position to be in given that (deep-seated gum disease) in the two not all UK graduates managed to secure a place at the time of writing. -

Staffordshire University Register of Collaborative Provision Section 1

Staffordshire University Register of Collaborative Provision Staffordshire University offers higher education awards in collaboration with a number of UK and international partners. This register provides details of our collaborative provision by partner institution. Section 1 shows courses in full approval. Section 2 shows partners and courses on teach out. Section 3 provides details of apprenticeship employers. Date of revision: June 2020 Section 1: Courses in Full Approval Study Course Name School Arrangement Type Mode Asia Pacific Institute of Information Technology (Sri Lanka Colombo Site) Partnership Start Date: 1999 BA (Hons) Accounting and Finance BLE Franchise FT BA (Hons) Law LPF Franchise FT BA (Hons) Marketing Management BLE Franchise FT BEng (Hons) Software Engineering CDT Franchise FT BEng (Hons) Software Engineering (two-year accelerated) CDT Franchise FT BEng (Hons) Software Engineering (with a placement year) CDT Franchise FT BSc (Hons) AI and Robotics CDT Franchise FT BSc (Hons) Computer Science CDT Franchise FT BSc (Hons) Cyber Security CDT Franchise FT BSc (Hons) International Business Management BLE Franchise FT BSc (Hons) International Business Management (two-year accelerated) BLE Franchise FT LLB (Hons) Law LPF Franchise FT LLM International Business Law LPF Franchise FT MBA Business Administration BLE Franchise PT MSc Computer Science (Business Computing) CDT Franchise PT Asia Pacific Institute of Information Technology (Sri Lanka Kandy Site) Partnership Start Date: 1999 BA (Hons) International Business Management -

Notes of the Cannock Chase Strategic VCSE Marketplace Networking Forum Held on 5Th December 2019 Rugeley Community Centre

Notes of the Cannock Chase Strategic VCSE Marketplace Networking Forum held on 5th December 2019 Rugeley Community Centre Present: Apologies: Michelle Cliff Support Staffordshire Anna Finnikin Everyone Health Lesley Whatmough Support Staffordshire Andy Cowan Diabetes UK Liz Hill Stafford and Cannock League of Hospital Friends Jane Reynolds SCVYS Jane Hinks Carers Hub Kate Waterworth Power for all Pat Merrick Cheslyn Hay Community Choir Lisa Atkins Cheslyn Hay Community Choir Gwen Westwood Dodd Cheslyn Hay Community Choir Jane Essex Cheslyn Hay Community Choir Susan Kingston Cheslyn Hay Community Choir Judy Winter Rugeley Stroke Club Laura Cranston Rugeley Stroke Club Ian Wright Healthwatch Caroline Campbell MPFT Sonia Evans Victim Support Nicola Speed Rugeley Library Alison Jacks Chasewood Shared Living Christina Bailey Chasewood Shared Living Wendy Owens St Mary’s Friendship Club Cath Hunt St Marys Friendship Club Laura Dunning Power for all Louise Hurmson SCC Libraries Chris Fielding Rugeley Community Centre Alan Dudson Councillor Liz Dale Police Sean Nicholls Police Maureen Evans Cruise Bereavement/ Case Fit Helen Titterton Transforming Communities Together Terry May Upper Moreton CIC Mike Sutherland County Councillor Tony Guy Support Staffordshire 1 1. Welcome, introduction and Housekeeping Michelle thanked all for attending the VCSE Market Place networking forum, including Cheslyn Hay Community Choir for singing some Christmas Carol’s and Rugeley Community Church for the Venue and Mince Pies. 2. Matters Arising Please note that in future Agenda’s will not be sent out by Locality Staff, they will be sent out by our Central Team. Notes of Forums alongside Agendas can be found on Support Staffordshire Website: www.supportstaffordshire.org.uk. -

As at 11 May 2020 Ar Surrogate Person Address 1 Address 2

As at 11 May 2020 Ar Surrogate Person Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 Postcode Telephone ; Diocese of Dio Lichfield Niall Blackie FBC Manby Bowdler LLP 6-10 George Street Snow Hill Wolverhampton WV2 4DN 01952 211320 [email protected] Diocese of Dio Lichfield Andrew Wynne FBC Manby Bowdler LLP 6-10 George Street Snow Hill Wolverhampton WV2 4DN 01902 578066 [email protected] Lich Rugeley Mark Davys Deer's Leap Meadow Lane Little Haywood Stafford ST18 0TT 01889 883722 [email protected] Lich Lichfield Simon Baker 10 Mawgan Drive Lichfield WS14 9SD Ex-Directory [email protected] Salop Oswestry John Chesworth 21 Oerley Way Oswestry SY11 1TD 01691 653922 [email protected] Salop Shrewsbury Martin Heath Emmanuel Vicarage Mount Pleasant Road Shrewsbury SY1 3HY 01743 350907 [email protected] Stoke Eccleshall Nigel Clemas Whitmore Rectory Snape Hall Road Whitmore Heath Newcastle under Lyme ST5 5HS 01782 680258 [email protected] Stoke Leek Nigel Irons 24 Ashenhurst Way Leek ST13 5SB 01538 386114 [email protected] Stoke Stafford Richard Grigson The Vicarage Victoria Terrace Stafford Staffordshire ST16 3HA 07877 168498 [email protected] Stoke Stoke-on-Trent David McHardy St Francis Vicarage Sandon Road Meir Heath Stoke-on-Trent ST3 7LH 01782 398585 [email protected] Stoke Stone Ian Cardinal 11 Farrier Close Aston Lodge Park Stone ST15 8XP 01785 812747 [email protected] Stoke Uttoxeter Margaret Sherwin The Rectory 12 Orchard Close Uttoxeter ST14 7DZ 01889 560234 -

The Bishop of Winchester's Deer Parks in Hampshire, 1200-1400

Proc. Hampsk. Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 44, 1988, 67-86 THE BISHOP OF WINCHESTER'S DEER PARKS IN HAMPSHIRE, 1200-1400 By EDWARD ROBERTS ABSTRACT he had the right to hunt deer. Whereas parks were relatively small and enclosed by a park The medieval bishops of Winchester held the richest see in pale, chases were large, unfenced hunting England which, by the thirteenth century, comprised over fifty grounds which were typically the preserve of manors and boroughs scattered across six southern counties lay magnates or great ecclesiastics. In Hamp- (Swift 1930, ix,126; Moorman 1945, 169; Titow 1972, shire the bishop held chases at Hambledon, 38). The abundant income from his possessions allowed the Bishop's Waltham, Highclere and Crondall bishop to live on an aristocratic scale, enjoying luxuries (Cantor 1982, 56; Shore 1908-11, 261-7; appropriate to the highest nobility. Notable among these Deedes 1924, 717; Thompson 1975, 26). He luxuries were the bishop's deer parks, providing venison for also enjoyed the right of free warren, which great episcopal feasts and sport for royal and noble huntsmen. usually entitled a lord or his servants to hunt More deer parks belonged to Winchester than to any other see in the country. Indeed, only the Duchy of Lancaster and the small game over an entire manor, but it is clear Crown held more (Cantor et al 1979, 78). that the bishop's men were accustomed to The development and management of these parks were hunt deer in his free warrens. For example, recorded in the bishopric pipe rolls of which 150 survive from between 1246 and 1248 they hunted red deer the period between 1208-9 and 1399-1400 (Beveridge in the warrens of Marwell and Bishop's Sutton 1929).