Identification of Pulling Factors for Enhancing the Sustainable Development of Agriculture with Special Reference to Maize in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE & 20TH INDIA CONFERENCE on Scientific Aspects of Vedic Knowledge Osfnd Kku Ds Oskkfud I{K

ASSOC D IA L T R IO O N W KNOWLEDGE F IS NECTAR O S R IE V D EDIC STU WAVES2016 InternationalConference Scientific Aspects of Vedic Knowledge oSfnd Kku ds oSKkfud i{k BHARATIYA VIDYA BHAVAN,NEWDELHI World Association for Vedic Studies (WAVES) (A Multidisciplinary Academic Society—Tax Exempt in the US) Wider Association for Vedic Studies (WAVES) (A Multidisciplinary Academic Society, Regd. in India) in collaboration with Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, New Delhi WAVES 2016 12TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE & 20TH INDIA CONFERENCE on Scientific Aspects of Vedic Knowledge oSfnd Kku ds oSKkfud i{k Abstracts of Papers Edited by: Prof. Shashi Tiwari Prof. R.P. Singh General Chair, WAVES 2016 Co-Chair, WAVES 2016 Dr. Umesh K. Singh Dr. Aparna Dhir Jt. Secretary, WAVES India Jt. Secretary, WAVES India December 15-18, 2016 Venue: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Kasturba Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110001 WAVES 2016 [12th International & 20th India Conference of WAVES] Organizing Committee: v Mr. Sashi Kejriwal, President, WAVES International, USA v Mr. Dhirendra Shah, Treasurer, WAVES International, USA v Prof. Bal Ram Singh, Director, INADS, Dartmouth, USA v Dr. Shashi Tiwari, General Secretary, WAVES, India v Prof. R.P.Singh, Philosophy, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India v Mr. Ravi Joshi, Member of Board, WAVES International,USA v Dr. Candace Badgett, Member of Board, WAVES International, USA v Dr. David Scharf, Member of Board, WAVES International, USA v Ms. Aditi Banerjee, Member of Board, WAVES International, USA v Dr. Ved Mitra Shukla, Delhi University, India v Mr. Ashok Pradhan, Director, Delhi Kendra, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, India Local Committee: v Dr. -

PHVO Industry and Its Compliance with Trans-Fat Regulations in India

2018 PHVO Industry and its compliance with Trans-fat Regulations in India Contents ABBREVIATIONS: .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................................................................................ 5 1. Backdrop .......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Objectives and Research Questions .................................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Specific Objectives of the Study: .................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Major Questions .................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Supplementary Questions ............................................................................................................................... 8 3. Methodology .................................................................................................................................................................. 8 4. Findings and Discussions ....................................................................................................................................... -

Botanical Elements As Revealed in the Vedas

114 BOTANICAL ELEMENTS AS REVEALED IN THE VEDAS Dr. Arundhati Goswami [Vedas are considered as the store house of every science of life. Human life is mainly associated with nature, which is closely connected with the branch of science called ‘Botany’. It is the scientific study of the physiology, genetics, ecology, distribution, classification and economic importance of plants. The seed of this branch of study in India is found since the Vedic period. The whole Vedic literature bears ample information of botanical data. Data regarding different classification of plants, their various parts, usefulness etc. are scattered in this area of study. This paper is a modest attempt to highlight the botanical information available in the Vedas to some extent.] Vedas are the root of Indian culture and the seed of almost all the branches of Science. Botany is one of those branches of science which is closely connected with nature. Botany means the scientific study of physiology, genetics, ecology, distribution, classification and economic importance of plants. Generally the study of this branch has two parts, i.e. Pure Botany and Applied Botany. Pure Botany is the study of all plants existed in the world, where as Applied Botany is the study of those plants which are useful to people. The history of Botany in India can be traced from the Vedic period. A huge number of information about both divisions of this branch are scattered in the whole Vedic literature and in various Vedic rituals (karmakānd a ). Here some of these concepts are discussed very briefly. A lot of indications of morphology of plants are traced in the Vedic literature. -

Vanaspati Ghee Industry. Production of Hydrogenated Vegetable Oil

Y_1465 www.entrepreneurindia.co Introduction Vanaspati is a fully or partially hydrogenated vegetable cooking oil often used as a cheaper substitute for ghee. Vanaspati is a desi vegetable ghee that has been hydrogenated and hardened. It is much cheaper than desi ghee. All brands of Vanaspati are made from palm or palm olein oil. Hydrogenation is brought about by using nickel as a catalyst in reactors at low to medium pressure. Vanaspati contains trans fats. It is used for cooking purposes in different domestic and commercial places. They are rich in the taste and flavor. www.entrepreneurindia.co Ghee is primarily used for cooking and frying and as dressing or toppings for various foods. It is also used in the manufacture of snacks and sweets often mixed with vegetables, cereals, fruits, and nuts. In some parts of the world, ghee is considered as a sacred product and is used in religious rites. It could also be mentioned that ghee is used in Ayurveda, which is a system of traditional medicine developed in India several thousand years ago and now also practiced in other parts of the world as alternative medicine. www.entrepreneurindia.co There are various different forms of edible oil found in the market. One of the old and most highly used form is the vanaspati ghee; this is a cheaper version of the pure ghee which is the most used and ancient form of fatty oil used by Indians made from cow milk. In India, the main source of trans fat is Vanaspati, a form of vegetable ghee that is a Partially Hydrogenated Vegetable Oil (PHVO). -

In the Atharvaveda Mieko KAJIHARA 0. in Later Texts, the Brahmacarin Is

Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies Vol. 43, No. 2, March 1995 The brahmacarin~ in the Atharvaveda Mieko KAJIHARA 0. In later texts, the brahmacarinis treated as a youth of the upper three classeswho studies the Vedas for a fixed term under his teacher, after having undergonethe rite of initiation (upanayana).Except for the single occurrenceof the word in the Rgveda (RV10. 109.5 = AV5.17.5, cf. n. 1), the oldest materials for the brahmacarinare found in the Atharva- veda (AV), where exists an independent hymn of the brahmacarin(cf. below),and occursthe wordelsewhere four times in the Saunaka (vulgate) version and seventeen times in the Paippaladaone (PS).1) 1. Among the occurrences,AV 6.108 and 6.133, the former dedicated to medha `intellectualfaculty' and the latter to mekhala'girdle', are worthy of specialexamination. AV 6. 1082)consists of a prayer for the medha,which is asked to come through the rays of the sun,s) and which the brahmacarinis said to have begun to drink first.4) The concluding verse states that the medhais caused to come by means of the daily prayer repeated three times a day.5) This daily prayer has a remote relationshipto the daily recitation of the Savitri verse by Brahminsfor the activation of their wisdom.AV 6.1336)sings of the girdle (mekhala) of the brahmacarinunder his teacher Yama.7)The third verse says that the brahmacdrinbinds a man with the girdle, taking him for Yama by means of brahman,tapas `heat' and srama 'toil'.8)In the fourth verse, to the mekhalais offereda prayer for intellectualfaculty and the power of senses,9) which reappears in an expanded form in the hymn of the brahmacarinto be examinednext. -

Trans-Free Vanaspati Containing Ternary Blends of Palm Oil–Palm Stearin–Palm Olein and Palm Oil–Palm Stearin–Palm Kernel Olein I

Trans-Free Vanaspati Containing Ternary Blends of Palm Oil–Palm Stearin–Palm Olein and Palm Oil–Palm Stearin–Palm Kernel Olein I. Nor Ainia, C.H. Che Maimona, H. Haniraha, S. Zawiah,b and Y.B. Che Manb aPalm Oil Research Institute of Malaysia, Ministry of Primary Industries, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia bFaculty of Food Science and Biotechnology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor ABSTRACT: Four samples of trans-free vanaspati were made drogenated oil, for example cottonseed or groundnut oil. As using palm oil–palm stearin–palm olein (PO–POs–POo) blends the industry grew, products based on blends of oils or animal (set A) and another four samples (set B) using palm oil–palm fats were produced. Presently, soybean, rapeseed, cottonseed, stearin–palm kernel olein (PO–POs–PKOo). Palm stearin iodine and palm oil (PO) are the most commonly used oils in the for- value [iodine value (IV), 30] and soft palm stearin (IV, 44) were mulation of vanaspati (3). These oils usually have to be hy- used in this study. The products were evaluated for their physical drogenated in order to achieve the required characteristics for and chemical properties. It was observed that most of the vanas- vanaspati. Hydrogenation is a fairly costly process and pro- pati were granular (grainy) and had a shiny appearance. Chemi- cal analyses indicated that vanaspati consisting of PO–POs–POo duces undesirable trans fatty acids. had higher IV (47.7–52.4) than the PO–POs–PKOo vanaspati Most of the trans fatty acid content in the human diet is (37.5–47.3). -

Trans Fat in Indian Food Supply: from Production to Consumption -A Case Study from North India

Trans fat in Indian food supply: From production to consumption -A Case study from North India Dr Suparna Ghosh-Jerath Associate Professor Indian Institute of Public Health-Delhi Public Health Foundation of India Outline • Trans fat regulation in India • Complexities of regulating trans fat in India • At manufacturer level: Industry perspective • At Retailer level : Vendor Perspective • At consumer level: Consumption pattern of the community Introduction • Consumption of industrially produced trans-fatty acids (trans fat) increases the risk of cardiovascular and other non-communicable diseases (NCD)(Micha & Mozaffarian, Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2008; Teegala et al, J AOAC Int 2009; Mozaffarian & Clarke,Eur J Clin Nutr 2009) • The WHO recommends that trans fat intakes should be limited to less than 1% of total energy intake and has called for the elimination of trans fats from the global food supply (Uauy et al. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009;WHO 2004) • Some high-income countries have mandated trans fat labelling, promoted public education campaigns and legislated an upper limit of trans fat in food products (Perez-Ferrer et al. Health Policy Plan 2010) • In India, the main source of trans fat is vanaspati, a form of vegetable ghee that is a Partially Hydrogenated Vegetable Oil (PHVO). (Ghafoorunissa, Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2008; Coombes R, BMJ 2011; LAe et al, Eur J Clin Nutr 2009) Introduction • Although the quantity of trans fat present in vanaspati depends on the brand, a Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) report suggests that levels could be as high as 50–60% of total fat content (Food Safety and Standard Authority of India (FSSAI ,2010) • In November 2009, the FSSAI proposed a regulation that included an upper limit of 10% trans fat in PHVO such as vanaspati, to be further reduced to 5% over three years. -

Characteristics and Production of Vanaspati, Ghee, Butter and Other Solid Fats

CHARACTERISTICS AND PRODUCTION OF VANASPATI, GHEE, BUTTER AND OTHER SOLID FATS Mike Willson LipoLogic Food Technology Consultancy Cary, North Carolina, USA E-mail : [email protected] CHARACTERISTICS AND PRODUCTION OF VANASPATI, GHEE, BUTTER AND OTHER SOLID FATS PRODUCT TYPES Vanaspati (or Vegetable Ghee) Ghee Butter/Butter blends Other solid fats TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION 1) Key product characteristics 2) Product development criteria 3) Production methods and process regimes 4) Future trends VANASPATI KEY PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS All purpose cooking fat Substitute for ghee Cost & availability Generally all vegetable Granular or grainy texture Degree of oil separation Melting point VANASPATI PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT CRITERIA Texture Oil separation Types of vegetable oil Melting point z Higher melting points used in Gulf countries ; 40-46 deg C z Lower melting points used in India, Pakistan, Egypt, & North Africa eg :- 31-40 deg C VANASPATI EXAMPLES OF TYPICAL FORMULATIONS GULF COUNTRIES - Commonly marketed as Vegetable Ghee - Generally, blends of palm oil & palm fractions - Melting points usually in the range 40-46 deg C - Often contain added colour & flavours COMPONENT AMOUNT Palm oil 40-60% Palm stearin 60-40% Antioxidant 0.1-0.2% Colour (Beta Carotene) 200 ppm Butter flavour qs VANASPATI PRODUCTION METHODS AND PROCESS REGIMES General points :- 1) Processed in much the same way as other types of shortening and bakery fats. 2) Process conditions dependent on :- z a. Formulation type z b. Degree of granular/grainy texture required 3) Packaging used -

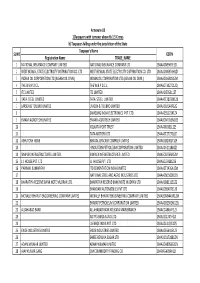

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

Development of Palm-Based Vanaspati (Vegetable Ghee): Effects of Crystallisation Procedures on the Product Texture

Journal of Oil Palm Research DOI: https://doi.org/10.21894/jopr.2020.0102 DEVELOPMENT OF PALM-BASED VANASPATI (VEGETABLE GHEE): EFFECTS OF CRYSTALLISATION PROCEDURES ON THE PRODUCT TEXTURE RAFIDAH ABD HAMID*; SIVARUBY KANAGARATNAM*; NORAZURA AILA MOHD HASSIM*; NUR HAQIM ISMAIL*; WAN ROSNANI AWG ISA* and NOOR LIDA HABI MAT DIAN* ABSTRACT Trans free vanaspati (vegetable ghee) formulated using a blend of refined, bleached and deodourised (RBD) palm stearin with iodine value of 30 (POs IV30) and palm olein with iodine value of 58 (POo IV58) in 40:60 w/w ratio was produced. The effect of mixing procedure on the crystallisation of the blend was investigated. VC-1 treatment which involved mixing of POs IV30 at 24ºC into POo IV58 at 65ºC and mixing the blend to a complete melt at room temperature followed by tempering at 25ºC produced a granulated vanaspati with spherical or granular shape crystals. VC-2 treatment which involved the mixing of POs IV30 at 55ºC into POo IV58 at 24ºC and mixing the blend to a complete melt at room temperature followed by tempering at 25ºC produced small crystals which is suitable for the production of smooth textured vanaspati. Vanaspati produced using VC-3 treatment which involved the mixing of POs IV30 at 24ºC into POo IV58 at 65ºC but was not mixed to a complete melt, followed by tempering at 25ºC produced small crystals and loosely packed structure which led to the formation of a slightly grainy textured vanaspati. Thus, a consistent and homogenous grainy textured vanaspati could be produced under controlled conditions using treatment VC-1 and this will be able to resolve the problem of inconsistency of texture in 100% palm-based grainy vanaspati. -

ESSENCE of TAITTIRIYA ARANYAKA Part 1

ESSENCE OF TAITTIRIYA ARANYAKA Part 1 ( KRISHNA YAJURVEDA) BY V. D. N. RAO 1 Compiled, composed and interpreted by V.D.N.Rao, former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, now at Chennai. Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda- Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence -

Gergely Hidas a Buddhist Ritual Manual on Agriculture Beyond Boundaries

Gergely Hidas A Buddhist Ritual Manual on Agriculture Beyond Boundaries Religion, Region, Language and the State Edited by Michael Willis, Sam van Schaik and Lewis Doney Volume 3 Gergely Hidas A Buddhist Ritual Manual on Agriculture Vajratuṇḍasamayakalparāja – Critical Edition and Translation Published with support of the European Research Council Beyond Boundaries: Religion, Region, Language and the State (Project No. 609823) ISBN 978-3-11-061765-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-062105-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-062049-8 ISSN 2510-4446 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 Licence. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Control Number: 2019934260 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Gergely Hidas, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing & binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements This research commenced some seven years ago when Dr Péter-Dániel Szántó provided information about the survival of the Vajratuṇḍasamayakalparāja in the original Sanskrit. Soon afterwards the ERC Synergy Project No. 609823 embraced the idea to pursue a thorough investigation and the present publi- cation is the fruit of this project work. Many thanks to Dr Michael Willis, Dr Sam van Schaik, Dr Péter-Dániel Szántó, Gergely Orosz, Professor Gyula Wojtilla, Professor Shanker Thapa, Deepak Bajracharya, Dr Csaba Kiss, Dr Dániel Balogh, Professor Max Deeg, Dr Kenichi Kuranishi, Hidetoshi Yoshizawa, Professor Harunaga Isaacson, Professor Francesco Sferra and the staff of the National Archives, Kathmandu, the Staatsbibliothek Berlin and De Gruyter.